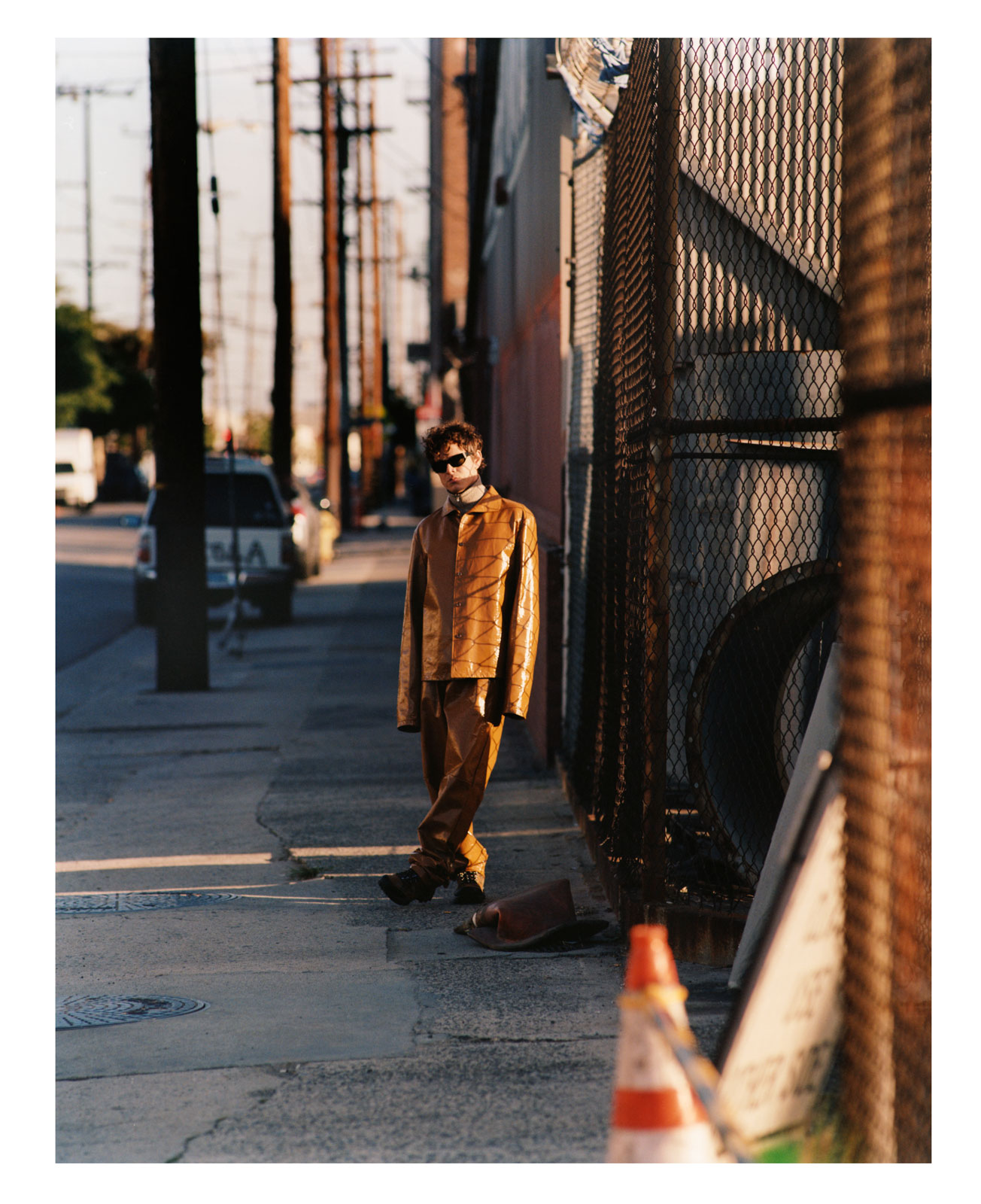

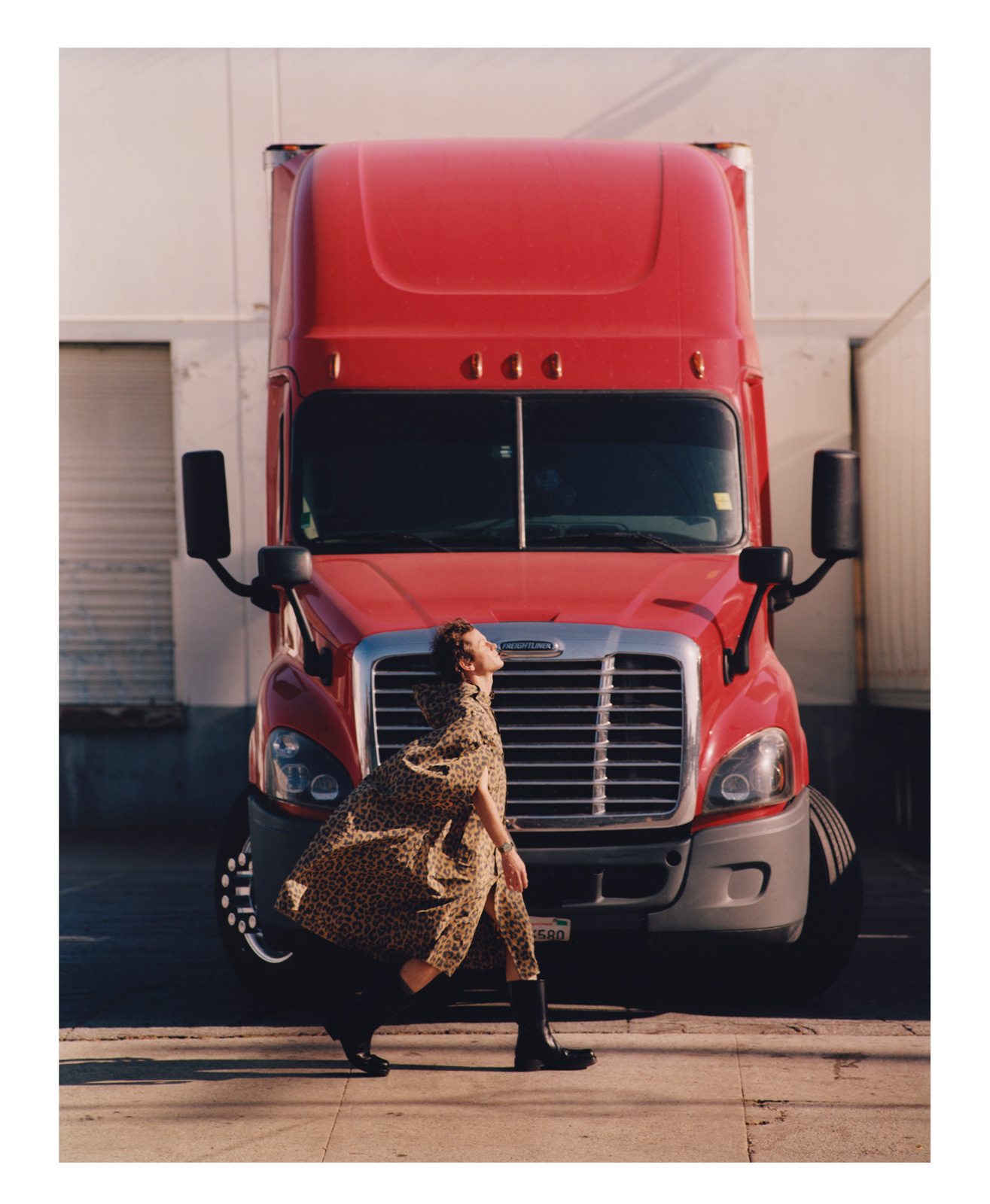

For Document’s tenth anniversary issue, musician Mike Hadreas reflects on the physicality of emotions and using anxiety as artistic fuel

“When I’m making music, I feel in control regardless of how chaotic or intense my feelings are, and I don’t really feel like that at all in my daily life,” says musician Mike Hadreas. “I don’t even feel like I can access my feelings sometimes. My therapist will be like, ‘How are you feeling?’ and I’m like, ‘I know I’m having a very strong feeling, but I don’t know what it is’ … In therapy I can’t explain it, and with a song I can.”

In the six albums he’s released under the moniker Perfume Genius, Hadreas has harnessed music to explore trauma, devotion, pain, and pleasure, creating shimmering experimental pop ballads about everything from erotic asphyxiation to the erosion of the body, a fascination informed by his personal struggle with Crohn’s disease. Eclectic in both genre and vocal register, his songs expand and contract with near-ecstatic reverence, falling to a whisper and then rising like a phoenix from the ashes; his lyrics bear witness to love, lust, power, and perseverance, navigating the challenges of selfhood through an unapologetically queer lens.

The visual iconography that accompanies his work is equally striking. Since he began releasing music in 2010, Hadreas has embarked on a journey of continuous metamorphoses, taking on personas that range from stiletto-wearing glam rock diva to shirtless, knife-wielding sex symbol. His subversive approach is exemplified by fiercely defiant queer anthems like “Queen,” a song that both deconstructs harmful stereotypes and depicts Hadreas exacting revenge on the forces that perpetuate them. (“No family is safe / when I sashay,” he sings through crimson-painted lips in the music video, strutting and flexing his muscles on a table lined with white male executives, their plates filled with shrimp.)

In recent years, Hadreas has been focused on getting in touch with his emotions—something he’s found to be inextricably linked to the body. “I don’t know how I forgot, or never realized, that feelings are physical,” he explains over Zoom, describing the process behind The Sun Still Burns Here, an immersive dance performance conceived in collaboration with choreographer Kate Wallach. “Writing music is the way I made it safe for the thoughts and ideas to come, and dance was the way I learned to experience my feelings physically,” he says, describing a woo woo rehearsal process designed to put dancers in touch with their bodies.

The body has been an ongoing theme in Hadreas’s work—from his 2015 record No Shape, which explores corporeal transcendence as a source of queer liberation, to the lush soundscape of 2020’s Set My Heart on Fire Immediately, which portrays the body as a site of joy, desire, and reclamation. These themes live on in his next record, Ugly Season, which adapts the music he composed for The Sun Still Burns Here to album form. A departure from the stylings for which he is best known, Ugly Season sees Hadreas stretch his sonic canon to its limit with a fluid amalgamation of musical improvisation and pop structures, creating something raw and beautiful in the process. “When I’m writing about my feelings, I’m naming them,” says Hadreas. “I’m able to be very patient with myself, because I feel like whatever I need to be doing, I’m doing. Wherever I’m being led, I go… I have a hard time accessing those feelings when I’m just sitting around, so I find these weird pathways that give me permission to do that. [Art] is a portal that I can go through to find myself.”

“A song can mean 30 different things at once, and it can have all these competing things going on, and somehow it still feels really satisfying and harmonious and liberating. I don’t get to feel that way very often about emotions.”

Camille Sojit Pejcha: I just listened to Ugly Season, which is so beautiful, and also quite different from your prior work. Could you tell me about the process behind the record?

Mike Hadreas: I keep forgetting that we’re putting out a record [laughs]. I have no idea what’s going on! That project began because me and the choreographer Kate Wallach decided to make a dance performance together called The Sun Still Burns Here. I needed an hour’s worth of music, but I also really wanted to create an album that could live on its own outside of the performance context.

Some of the songs are longer; I was not tied to having everything be in a pop structure, though I forged those structures on top of some of it, which was fun, too—trying to put a verse over something experimental and improvised and wrangle it into that. It was kind of maddening, but those ended up being my favorite songs. ‘Hellbent’ and ‘Eye in the Wall’ were both born from improvisations between me and my partner Alan [Wyffels], and Blake [Mills], my producer. And then I went to the studio and tried to write a pop version of that, imposing a verse and chorus on top of these elements that were shifting without care.

Camille: What was behind the decision to make songs you could perform to as a dancer?

Mike: I always wanted the dance and music to be fully enmeshed—I didn’t want to be on the side, playing this textural ambient music while the dancers were onstage, and Kate agreed. Throughout the project, our sensibilities kept lining up. I’ve never really made anything where someone else was so involved from the very beginning.

Camille: Did you find it freeing to do something so collaborative, where it wasn’t all on you?

Mike: I usually don’t like that! I have very clear ideas, but I have a hard time communicating and clawing my way to the top when it comes to asserting myself in situations with a lot of people. With Kate, and even the other dancers, I just felt heard. I usually hate criticism—I’m very sensitive—but getting feedback on my performance from them wasn’t crushing because I felt this core respect and understanding between us, which is something I have a hard time with. Mainly with men [laughs].

Camille: Many of your music videos also feature you as a performer, often within a really fully developed and elaborate visual world. How do you go about creating a persona for each project?

Mike: It changes with each thing I make. When I first started, the scale was much smaller; I was creating the music myself in my bedroom, and then making these YouTube videos in the style of found footage that I would edit. As time went on, they became more collaborative. These days, if I wanted to, say, have a car explode, I would probably have to have multiple meetings in order to make it happen—but unfortunately, I could probably make it happen [laughs]. My tool set is bigger, so I can dream bigger. The same is true for writing the music; it can go beyond just my capabilities.

Camille: Referencing this idea of capability, is there anything you feel like you can do through music that you don’t necessarily do in life? A core difference between you and your onstage persona?

Mike: When I’m making music, I feel in control regardless of how chaotic or intense my feelings are, and I don’t really feel like that at all in my daily life. I don’t even feel like I can access my feelings sometimes. My therapist will be like, ‘How are you feeling?’ and I’m like, ‘I know I’m having a very strong feeling, but I don’t know what it is.’

When I’m writing about my feelings, I’m naming them. I can harness energies and emotions and everything feels sort of manageable, because I’m directing it. I’m able to be very patient with myself, because I feel like whatever I need to be doing, I’m doing. Wherever I’m being led, I go.

Then there’s the physical aspect: Being onstage, I experience a real sense of kindness and warmth toward myself. I feel hyper-present, and I don’t always feel that way offstage. That used to be okay with me—performing was my job, so I reserved everything for my work. But recently I realized I want to feel good more often—not just when it’s shareable. I want to feel good just for me. I have a hard time accessing those feelings when I’m just sitting around, so I find these weird pathways that give me permission to do that. [Art] is a portal that I can go through to find myself. I’m super lucky, but also, it feels like I turn on and turn off a lot.

“I’ll go into it, and in doing so, I’m making the container for [that feeling or memory]. I’m making a whole world for this thing to live in. Sometimes I leave it as it is, and sometimes I put an outfit on it.”

Camille: It sounds like performance is a really powerful context for you. How has your relationship with your body and emotions evolved since you started to focus on dance?

Mike: I don’t know how I forgot, or never realized, that feelings are physical. They’re not ideas or concepts. I thought that’s what feelings were for a long time, that thinking about feelings was feeling. But it’s not. It’s a physical thing. Through performing, and all these exercises that make you feel really connected and present, I’ve been able to access that more. Writing music is the way I made it safe for the thoughts and ideas to come, and dance was the way I learned to experience my feelings physically. Sometimes in rehearsal, doing these movements, I would unlock something in my body and just start crying. It was pretty wild. A lot of that was just being tender and nice to myself. I don’t know, it’s hard to talk about it and not have it sound hokey. It feels pretty hokey, honestly.

Camille: Sometimes life is hokey!

Mike: [Laughs] There’s something very intimate about being touched and carried and rocked, and doing the same for others… I’m not a trained dancer, so when we’re all doing all those things, it’s not official business for me. I don’t have the same relationship with my body that they do; they’re kind of used to receiving that physical information and stimuli, so to do that as someone who wasn’t was really powerful.

Usually [when you’re physically intimate with someone], a lot is already plotted out for you. But with the rehearsals, there was no real map for it; it wasn’t sexual, it wasn’t goal-oriented—it was just an energetic exchange between bodies. Touch and kindness mixed with performance, which kind of changes everything. It makes the energy in the air feel very charged, but you’re safe from being too intimate.

Camille: Do you feel that performing makes it safe to explore your feelings, because there’s a natural limit to where you can go versus what you might do when you’re alone?

Mike: I don’t usually feel safe, even alone—so it doesn’t matter if there’s one or two people, or if there’s 10. The last time I remember feeling safe was before I knew I wasn’t, when I was little. There’s lots of play involved in these rehearsals, and in some ways, it’s really childlike—we weren’t just doing choreography, we were rolling around on the floor and staring at the wall and crying for two hours. It’s honestly all I want to do now. I’m done with music. I’m ready to have a big farm with friends and have some cult-y teachers come in and carry us all through some weird exercises.

Camille: That’s the dream.

Mike: [Laughs] It’s literally just called a cult, but…

Camille: It sounds like what you’re describing is this sense of creative play that isn’t part of most adult contexts. But it can be attained through art.

Mike: I think that’s what it is.

Camille: Do you often feel like you’re intentionally reclaiming and recontextualizing things in your life through your work, or is it something that happens in retrospect?

Mike: There’s a particular choreography to that; sometimes it’s very intentional, where there will be something that’s bothering me or some memory that’s coming up or something that I can’t even access, but I know it’s there. I’ll go into it, and in doing so, I’m making the container for it. I’m making a whole world for this thing to live in. Sometimes I leave it as it is, and sometimes I put an outfit on it. But I don’t force it—it doesn’t have to be explained concretely. In therapy I can’t explain it, and with a song I can—and a song can mean 30 different things at once, and it can have all these competing things going on, and somehow it still feels really satisfying and harmonious and liberating. I don’t get to feel that way very often about emotions. I feel like I’m supposed to pick one thing to feel, but I have a lot going on!

Camille: Art seems to allow space for that plurality in a way that language and other things don’t. I interview a lot of artists and musicians, and I’m interested in how different people reference this kind of container, or this creative structure that allows you to ‘go there.’

Mike: Do you talk to people who aren’t so sacred and precious about art? I sometimes work with amazing people whose work I love, and who I love talking to, but I feel like they’re not thinking of it like this—they’re not channeling, they’re not tapping into some spiritual thing.

Camille: In my experience, younger artists don’t always have the language to describe what they’re doing and what the spiritual aspect is, even if they do have it. With people further into their careers, who have built a relationship to the creative process over the course of many years, there is usually some kind of sacred aspect to what art has come to mean to them personally, and what they’re trying to do with it. It’s always this interplay of what you’re trying to do with your work—what you’re trying to achieve—and then what it means to you.

“I’m not very ambitious, really. I want money and I want success, but I don’t want to have to do anything different to get it!”

Mike: I’ve been workshopping ‘the formula’ with a lot of my friends, ‘cause we’ve been playing shows again, and we’re like, ‘Is the show good? How do we know?’ We all have different ideas when we get offstage about the performance or the audience. Like, ‘Was the audience quiet or loud, and what does that even mean?’ Sometimes I go to see a show and I love it, and I’m obsessed with it, but I’m not screaming the whole time—so why should I feel like it wasn’t a good show because they weren’t screaming? You phase in and out of feeling hyper-connected to what you’re doing in the moment, and then feeling a little more self-conscious in retrospect. So how do you stay present? We can never really figure it out.

Camille: It’s a moving target! I’m curious to hear how your personal definition of success has changed over time—not, like, what it means to ‘make it,’ but the changing shape of what is fulfilling and satisfying creatively, in the moment.

Mike: I’m not very ambitious, really. I want money and I want success, but I don’t want to have to do anything different to get it! I sometimes feel guilty that I don’t do a lot more self-promotion or I’m not more ambitious. But I hate doing stuff. I don’t like doing anything [laughs].

Camille: I feel you. The current creative ecosystem, and the exposure economy, really privilege people who can throw themselves into self-promotion as well as the creative process itself.

Mike: People who are naturally good at that must just have some mechanism that I don’t. It does make me feel like I’m doing something wrong sometimes, because I’m not driven in that way, but I still want all of the things that they get.

Camille: I feel like having to perform your personality in public is a bit of an unfair add-on. That said, you’re very funny on Twitter.

Mike: I just like making things. Sometimes I feel like there needs to be some cohesion among all of it—that there needs to be some world-building. But I’m just doing stuff when I feel like it. With some people, I can tell they’re really thoughtful and intentional about everything that they are putting out, but it still feels soulful and authentic. Caroline Polachek is a good example of that.

Camille: Do you think she feels that way about her work? Does anybody?

Mike: I think if you did, you’d just stop making things. I try to carry my anxiety around certain things as fuel. It’s part of the creative process, the same way you think of having writer’s block being part of eventually writing. I don’t think of them as two separate things anymore.

Camille: I like that idea, that the doubt and anxiety are part of the process. As someone making music about the queer experience before [doing so] was widely accepted, did you ever feel that you were able to cultivate self-confidence from a place of rebellion, to oppose the people who didn’t accept you?

Mike: Growing up gay, I learned pretty quickly that the way I talk or move could get me into trouble. Then, in my music, I took all of the things I had been bullied for and turned them into something. My career was built around those things, and now they’re being celebrated—but my whole life, I’ve just been saying ‘Fuck you, I’m going to do it anyway!’

In the beginning, a lot of my music was about trauma and memories and trying to sort through things. Now I feel like I’m trying to unpack all of that and get back to who I was before the world got to me—before I became self-conscious in a way that was limiting my instincts. Music and writing is how I unburden myself of that, and feel free again.

Grooming Shea Hardy. Photo Assistant Chris Llerins. Stylist Assistant Ella Jepsen. Production Ms4 Production.