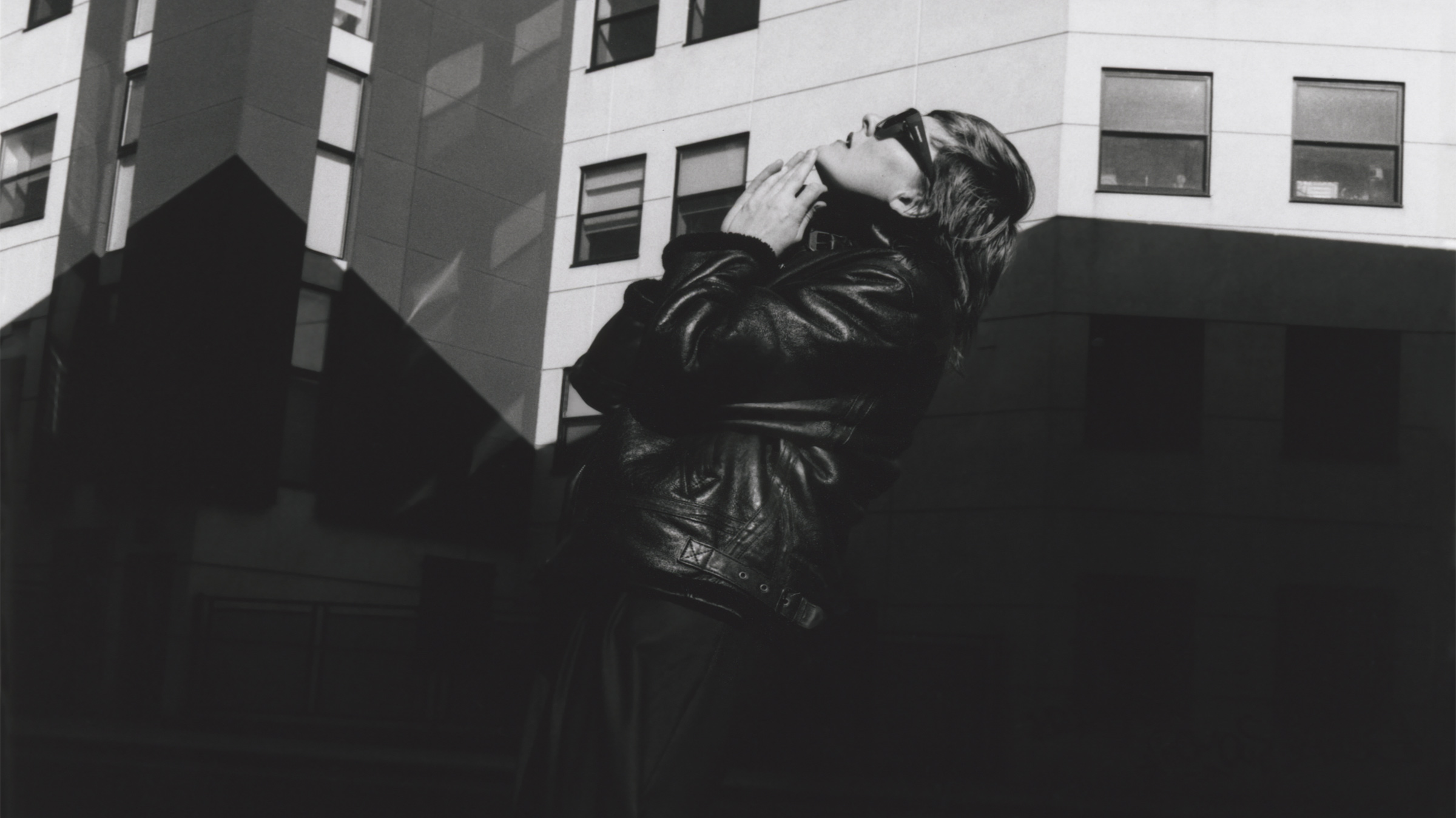

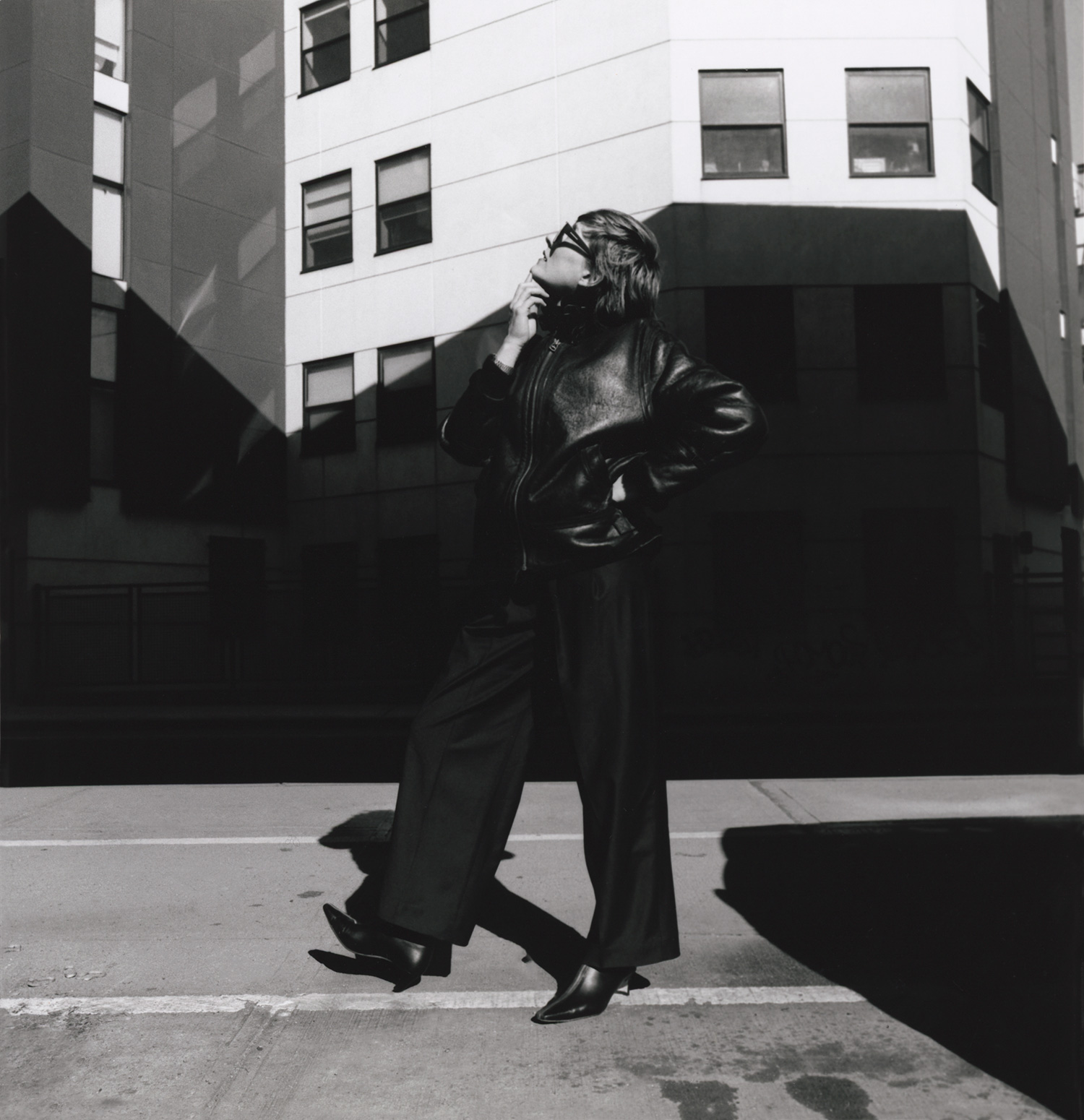

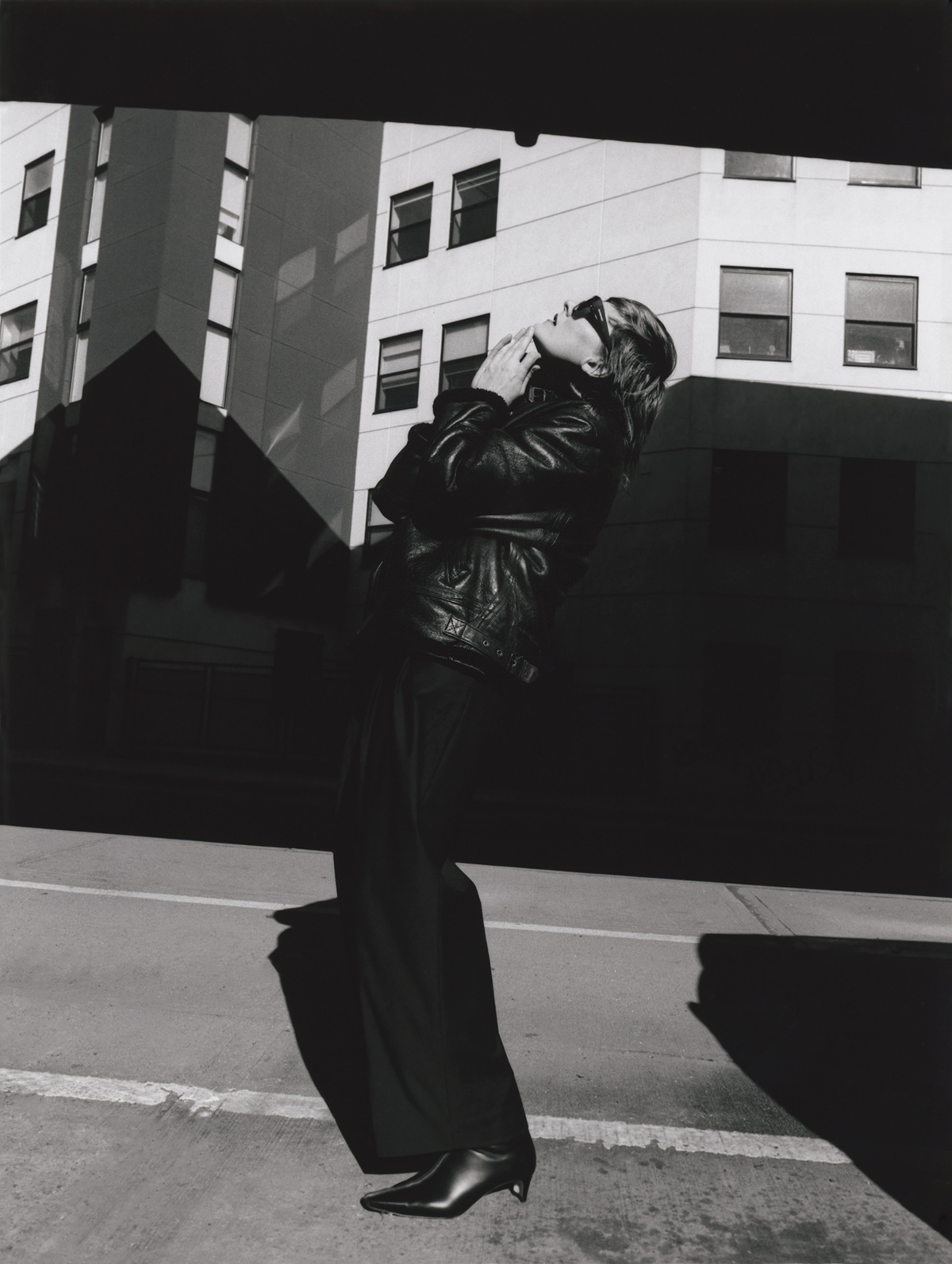

In the wake of her latest record 'Pompeii,' the art pop iconoclast joins Document to discuss creative transference, childhood escapism, and the difference between solitude and loneliness

“The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be, I think,” wrote Virginia Woolf in her journal in 1915. It’s a bold statement, and one that has incited responses from other creatives—from Rebecca Solnit’s celebrated essay on the subject, to Pompeii, the latest offering by Welsh musician and producer Cate Le Bon. In her sixth studio album, Le Bon summons images of the apocalypse—one that, during the process of creating this quarantine record, seemed to be occurring right outside her door.

Plunged into uncertainty at the height of the pandemic, Le Bon found comfort in embracing the unknowability of what lies ahead—something that became a source of liberation in a moment when many were searching for certainty. “When there’s that sense of, This could be the last thing you ever make, there’s a beautiful freedom in that,” she says, noting how Solnit’s essay on Woolf inspired her approach to this chaotic new reality. Surrendering to the present moment is not a new practice for Le Bon; if anything, creating from deep within her own experience is a way of going back to her roots. As a child, Le Bon recalls a sense of total escapism—one she now channels into her creative process as a musician. “I like to totally remove myself from everything, so that you are able to create like when we were children—when you could just sit for hours making something, without this idea of what comes next,” she says. “I was raised playing outdoors, employing only your imagination. There’s no better feeling than going into the woods, getting lost, and knowing that you’ll eventually somehow find your way home.”

Le Bon is known for pushing musical boundaries—but no matter how far she strays from the beaten path, she manages to return home to a singular sound all her own. Pompeii sees Le Bon play guitars, synths, bass, piano, and percussion, mingling her ephemeral vocals with kaleidoscopic textures composed entirely “in an uninterrupted vacuum.” In Pompeii, Le Bon holds a magnifying glass to emotion, her lyrics alternating between surreal abstraction and personal address that bring the force of her insight to bear with a scorching focus. (“Call it a war, you can do what you like / heavens above don’t care how you’re living,” she sings in “Harbour,” concluding that “bravery’s just an emotional bribe.”) There is a shapeshifting, protean quality to her songs—a striking poeticism that catches you off guard and delivers moments of clarity, before their meaning slips from your grasp. Such is the work of Cate Le Bon: Approaching truth at a slant, her music captures the fundamental mystery of the world around us, and the pleasure in seeking meaning from it.

Camille Sojit Pejcha: Could you talk a little bit about the role of Tim Presley’s painting in inspiring the album art, and your approach to the album?

Cate Le Bon: Yes. It was made at a time when we were searching for words that didn’t really exist to express how we were all feeling. In Tim’s painting, we found an expression that resonated with us. For me, the idea that the painting didn’t exist earlier that day, and now it did, was such a beautiful reminder of the power of art—the conjuring of an image from what seems like nowhere, with no notion of where it comes from. [Drawing inspiration from the painting] felt like this transference of creativity, from one expression into another expression. It had this really strong presence throughout the whole session and process of making the album.

“The work no longer belongs to me—it can now be interpreted in so many ways, and none of them are right, and none of them are wrong.”

Sometimes you can almost choose and curate what your inspirations are, and then there are times when something completely bowls you over and you’re totally porous to it. And that’s real inspiration—it’s such an amazing feeling.

Camille: In regards to choosing your inspirations, I noticed there was a line in the description of Pompeii about how you incorporated discipline or rules into your creative decision-making. Could you say more about that?

Cate: We made this record in a different way than we had anticipated. Pretty soon you realize, when there’s a global crisis, any plans you have are totally incompatible with reality. So there was a sense of throwing ourselves into that chaos, and allowing ourselves to just absorb everything. But at the same time, you have to have some kind of disciplined self-indulgence. You have to keep one eye on the process.

There are things that I’ve been doing for years, or rules that I’ve kind of made for myself without realizing. I don’t use acoustic guitar in a record because it reminds me too much of playing shows on acoustic and being dubbed a folk artist, which drove me mad for so long. But then, there’s realizing that those things probably don’t serve you anymore. There was a call for an acoustic guitar on one song and we just surrendered ourselves to everything we could. When there’s that sense of, This could be the last thing you ever make, there’s a beautiful freedom in that.

Camille: The description of the album also mentioned that a lot of its themes germinate from your interest in antiquity and philosophy, as well as divinity. Are there any core phrases or philosophical lines of thought that come to mind, which you thought of as a guide or inspiration to your process?

Cate: There’s one essay that I keep coming back to over the years, which is the Rebecca Solnit essay on Virginia Woolf.

I think John Keats coined the phrase ‘negative capability,’ which was a useful concept to remind myself of while making a record during a global crisis. I was remembering that hope and curiosity are different from optimism and leaning into that, because optimism and despair have no action behind them. Being okay with not knowing, instead of trying to convince yourself that you know something, became this liberating way of thinking when things were particularly bleak. And then that Gaston Bachelard book, The Poetics of Space, is one I keep coming back to. You can read a chapter here and there and it resonates in lots of different ways, with lots of different situations. All of that feeds into my absolute love of Dadaism and all the Cabaret Voltaire stuff, and that idea of interacting through absurdity. That’s mostly where the record lived in my mind.

Camille: This idea of making peace with not knowing, versus having your well-being hinge on the idea that things are going to be okay somehow, requires a certain willingness to acknowledge the illusory nature of control in the first place. It reminds me of something you’ve said before, which is that as an artist, you don’t imagine yourself from the outside. How did you arrive at this form of surrender, and has it always been a part of your practice?

Cate: In that Rebecca Solnit essay, Virginia Woolf talks about the enormous eye. It’s something that’s only getting harder to avoid; with social media, there’s always an audience if you want it, even in the moments that should be private. For me, tapping into that audience would be so detrimental to creating something—this idea that you’re opening the window to everyone, but also to a perceived idea of everyone that comes from your own mind. Your version of the audience might deviate from the real audience, and likely not in a good way.

I don’t really have a repeatable process when it comes to making a record, but there are conditions that I know I will do best under. I like to totally remove myself from everything, so that you almost become invisible, and feel invisible, and are able to create like when we were children—when you could just sit for hours making something, without this idea of what comes next, or how it will be received. Just the pure joy of making something. I’m always trying to find that feeling, because I think that’s when you’re most likely to make something authentic. If I was a fan of a musician, I wouldn’t want them to be making something with one eye on the audience. I would want them to be making something that’s from them, whether I end up liking it or not.

Camille: Since you’re honing in so deeply on your own creative experience, I’m curious what it’s like to later try and open it up and translate it to the world when it’s done. For instance, your music videos have such a strong sense of artistry and surrealism in the costuming and the art direction. Could you tell me about your process behind that?

Cate: I always struggle with the point that a record that you’ve crafted in total privacy becomes very public all of a sudden. There’s no transitional period. There’s a moment when it’s yours, and then there’s a moment when it no longer belongs to you.

This time, I kind of surrendered the music videos to artists who I trusted, in the spirit of trying to continue that creative transference: from Tim’s painting to my record, to how another artist would decipher and conceptualize what was going on… Almost allowing myself to become a puppet for these artists, who I trusted to make these videos, was an acceptance of that as well. When it’s released, the work no longer belongs to me—it can now be interpreted in so many ways, and none of them are right, and none of them are wrong.

Camille: I’m curious to hear a little bit about your upbringing–what the atmosphere was, which parts you took with you, and which parts you rejected or grew away from?

Cate: I grew up in a small hamlet—it wasn’t even a village—in Wales, in an old farmhouse. Since we lived in the country, I was raised playing outdoors; it sounds ridiculous, but we’d spend the weekend walking our goats or making dams.

There was this idea of total escapism, employing only your imagination. There’s no better feeling than going into the woods, getting lost, and knowing that you’ll eventually somehow find your way home. That is the thing I’m always chasing: the feeling of going into the woods and being totally invisible. As a kid, it’s one of the most exciting things: You’ve gone out by yourself and you don’t know what field you’re in anymore, and you could be hours away from home. To be honest, I still crave climbing trees and rocks and all that stuff, but it’s not so socially acceptable! [Laughs]

Camille: It sounds like you really channeled that into your creative process.

Cate: I think so. When I went to Stinson to make the record Crab Day, it was the first time I made a residential record. I experienced the benefits of being away from the comforts and the things that distract you. For everyone to exist in this little vacuum together made a world of difference in how connected you are to the output.

“I was raised playing outdoors, employing only your imagination. There’s no better feeling than going into the woods, getting lost, and knowing that you’ll eventually somehow find your way home.”

Camille: Your sound is so distinctive, both across the different songs in an album, and across different albums. I’d love to hear what your experience was like with musical mentors—people opening the door to encourage you to explore in a way that felt authentic, as well as what challenges you faced.

Cate: I was really lucky in my first experience in a studio. A close friend of mine, Krissy Jenkins, saw me play a show, and he said, ‘Come and make a record with me.’ I was so green and had no idea what that entailed. And so we worked: I’d go to the studio everyday, and we’d work on what I thought was a record. He never told me anything wasn’t possible, and I’d have an idea that was probably pretty naff—just as someone who was excited about the possibilities of reamping drums and making them sound all blown-out, and all these things that are so exciting when you’re in the studio for the first time. He would never say, ‘No, that’s not possible,’ or, ‘That’s a waste of time.’ He’d never obstruct me; he had no designs of pinning his own agenda on me.

I didn’t realize how generous that was, and what an incredible first experience it was for a young woman in a studio, until years later when I had my first bad experiences—where you have people trying to pin their agenda on your creative process. And then I found Samur [Khouja], who possesses the same kindness and openness; he knows when to give me space, but still offers direction. I really treasure it now, especially having had experiences where you’re creatively obstructed, and you’re told you’re wrong, and you’re told all the things that women get told. I hope you can hear that in the music: the sense of curiosity that we both have. Neither of us has any preconceptions of what ‘cool’ is, so we make whatever feels really good to us, and gets us both laughing or crying. I feel really lucky to have found him to work with.

Camille: Sounds like a really beautiful creative partnership. How did you get interested in making music earlier in your life? What was the beginning for you?

Cate: I think I was always drawn to music. Growing up, there was no television—on the weekend, my parents played their music in the mornings, and then we’d get kicked out of the house to play with our goats. Dad bought me and my sister acoustic guitars when we were seven and eight, so he had someone to jam with. There was always joy behind it. It was never Do your scales, or an academic version of music. But the school we went to was a Welsh school, and music is so coveted. It’s all singing competitions; everyone’s incredible at harp and piano. I was just left by the wayside with all of that stuff. There wasn’t really an entry point in school for me to make music in the way that I wanted to make music.

But all of a sudden, one day there were posters around school for this local band competition. Me and my friend secretly started a band together so that we could compete against all the kids that were number one at singing, and all that competitive stuff. We kept it a secret. And then we won! And they couldn’t believe it, you should have seen their faces—it was like a teen movie, where the shit kids win.

Camille: I would definitely be like, ‘I’m doing this as a career now.’

Cate: Yeah, I just carried on playing. It was the only thing I cared about. My dad bought me a little digital recording studio box, so I could just be in my room making little demos until I moved to Cardiff and started playing in people’s bands.

Camille: You mentioned your family playing music in the morning. What kind of stuff did they listen to, and what were you into growing up?

Cate: I remember that when I was bringing home tapes I borrowed from the boys at school—the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Deftones—my dad, who was really into music, sat me down and played Pavement for me for the first time. I’d never heard music like that before.

I was 13, and I still remember it. It was the first time I could see the construction of everything—the instruments, the way you can have different styles when you play guitar, and Stephen Malkmus’s songwriting—and the way everything was at the precipice of falling apart, but was so beautiful… At that age, you just want to fall in with everyone, but I loved Pavement so much, I didn’t care that no one else at school had heard of them.

My dad was really into Neil Young and Steely Dan. When I’d go and stay with him, we’d drive around and listen to The Beatles and Crowded House, and sing our hearts out.

Camille: You now live in the desert, in California. What drew you there, and what makes you want to stay?

Cate: I wanted to make a record in LA because it sounded like a wonderful thing to do. I’d been in Cardiff for so long, and we had the same awful weather every day for about two years. My partner at the time and I got these three-year visas, and we were like, ‘Why not go do something different?’ We had been presented with this opportunity, and we knew some generous musicians out there, so we just gave it a go. We met really wonderful people and learned so much from working with a different pool. We just loved it. And then I moved back to the UK for a bit to go to furniture school; I went to the total opposite of LA, which was a tiny, tiny village in the Lake District. I was there on my own for about a year and a half and went to furniture school every day, and then I moved back to America. But over the pandemic, I was stuck in Europe, unable to return to the US. It’s been a bit of back and forth for a few years.

Camille: I’m curious about this interlude of going to furniture school in the midst of your musical career. What inspired that?

Cate: I love music so much, but I think I’d been doing music for so long that I felt like I was getting a bit jaded and fatigued; my attitude was on a downward spiral. So I thought I would take the pressure off and let it kind of breathe for a bit, and check in on whether it was habit or heart that was driving the ship. At the time, I thought the only way to really give it some breathing space was to throw myself completely into something else. So I went to furniture school in a little village called Staveley, which was an intensive, year-long program of learning master craftsmanship, working with solid wood and hand tools. It was insane in a way, because I had made the decision to do it, but I don’t think I had fully connected with what it meant. Within a week, my life changed in a way that was totally unrecognizable. I was going to furniture school in my overalls, and living in this tiny, little cottage by myself.

“Solitude doesn’t mean being a hermit, and solitude isn’t loneliness; to me, solitude means really valuing the time that you spend by yourself, so that it makes you value the people who you let in.”

Camille: Was there anything you learned about yourself there that changed your approach to music when you came back to it?

Cate: I realized that you need to put your motives back in check. You can’t allow the peripheral things to steer the ship. Everything should be on your terms, and you shouldn’t compromise when it comes to something you love so much, because that’s when you start to get fatigued creatively, and things start to go awry. So it was a real reminder of that. I also think that having something else to take the onus off the thing you love so much frees you up. You’re not gripping the reins so tightly. It was liberating and really informative.

Camille: You sound like you have such a balanced approach to creating—I’m curious how you keep yourself grounded on a daily basis, when you’re not going off to furniture school.

Cate: I would attribute that to all of the wonderful people I have in my life. I also think of Gruff Rhys from the Super Furry Animals, who was one of the first musicians who took me under his wing; the way he conducts himself professionally and personally was such an inspiration to me, because he would never compromise, but did so in such a peaceful, honest, and authentic way. That was really inspiring.

It’s been such an up-and-down couple of years—I don’t really have a routine. Just having really wonderful people around me is so important; when I tour, I tour with incredible women, and incredible men who respect women. It all makes a huge difference in your enjoyment and your involvement in something that can be pretty taxing at times.

Camille: There is seemingly this contrast between the rich creative community that inspires and supports your work, and your need to withdraw from society a little bit and create in a vacuum. Do you feel like having that support network lets you go further into the woods, so to speak?

Cate: I think it’s the idea that, when you spend time with other people, you’re choosing to give up time that you could spend by yourself—it has to mean something, so by embracing that, you end up with incredible people in your life.

Solitude doesn’t mean being a hermit, and solitude isn’t loneliness; to me, solitude means really valuing the time that you spend by yourself, so that it makes you value the people who you let in.