Exploring themes of intimacy, class, and self-expression, the photographer captures moments of human connection on the margins

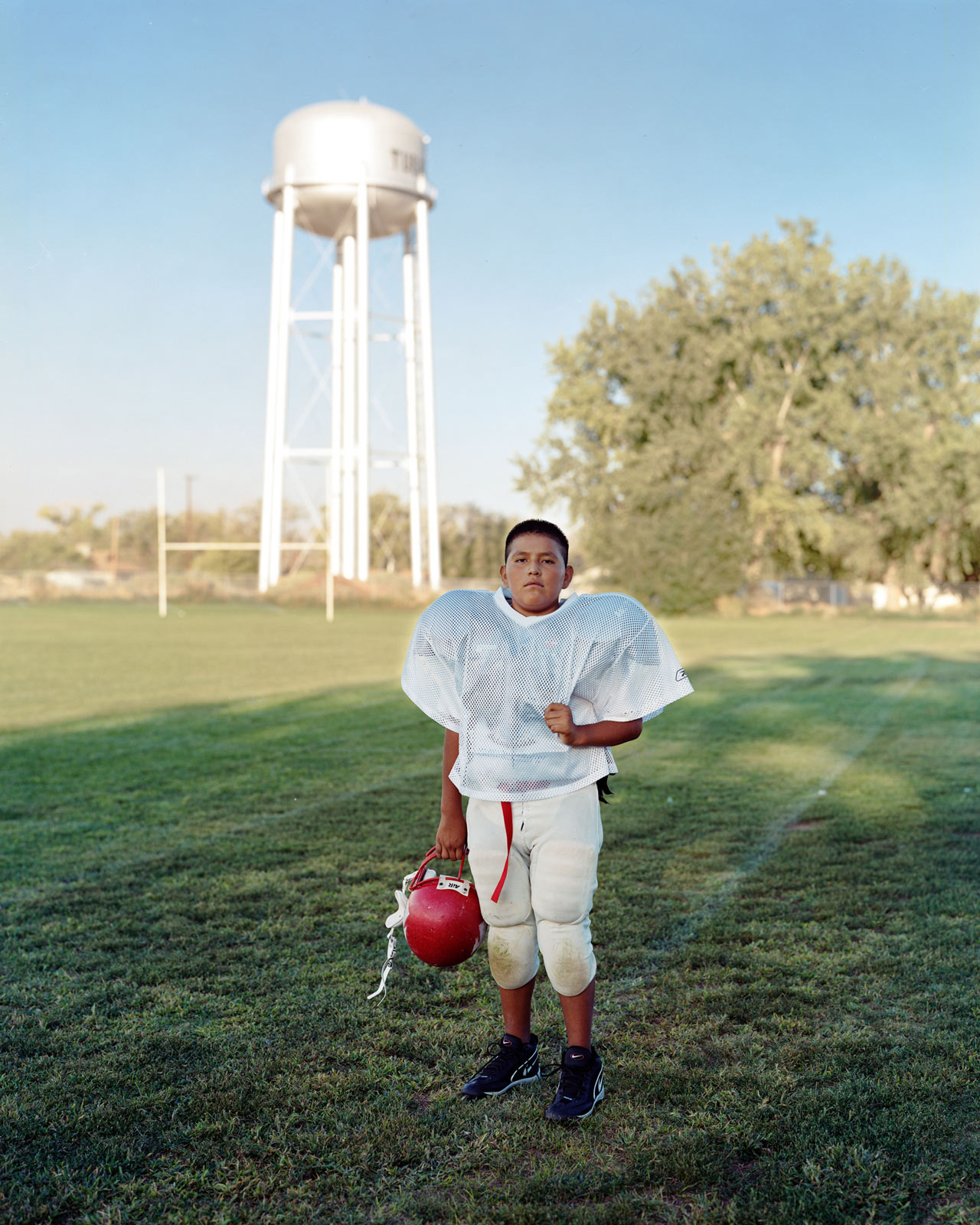

New York-based portrait photographer Richard Renaldi uses an 8×10 camera to photograph his subjects, most of whom are strangers he met in public. Created primarily within the context of specific communities, his portraits explore themes of intimacy, class, and self-expression through a documentary-style aesthetic. Renaldi’s photographs are a celebration of both individuality and togetherness.

“I’m trying to find a way for the stories I tell to be relevant to my own story, yet also connect to other people’s experience in life,” says Renaldi.

His 2009 monograph, Fall River Boys, documents young men in the post-industrial mill town of Fall River, Massachusetts. Capturing his subjects on the cusp of adulthood against the backdrop of an uncertain future, Renaldi portrays a narrative of possibility among darkness. Touching Strangers, published by Aperture in 2014, depicts strangers who have been posed by the photographer so as to be physically touching. These images, which were taken over a seven year period across the United States, encourage us to consider what kind of world could be possible by using genuine human connection in a diverse society to mend social rifts. Published by Aperture two years later, Manhattan Sunday tells a story of Manhattan’s LGBTQ nightlife scene through the perspective of people leaving nightclubs between midnight and 10am on Sundays. Renaldi impossibly captures the impermanent moments of the party that will never really end, while highlighting the nuances of individual experience.

The photographer’s long-running series Pier 45, which he began shooting in 1994, is a diaristic documentation of New York City’s Christopher Street waterfront. Pier 45 can only be described as a homage to the queer history of the piers and the safe spaces that were created against it’s backdrop. From NYC’s Hudson River Park, Renaldi joins Document to discuss the importance of questioning one’s authority as a storyteller and the resilience of the queer community of Manhattan’s West Side piers.

Avery Norman: What was your first conscious aesthetic experience?

Richard Renaldi: I don’t know if I can think of the very first conscious aesthetic experience, per se. I loved looking through books. I had picture books as a little kid and I had an encyclopedia. I used to love looking at the drawings in the encyclopedia. They had these cellophane things of the human body and they overlaid each other. The textures of the ’70s really influenced me. We had yellow shag carpeting in our living room and we wore the shirts with the wide collars, so that really etched into my mind. There was just something very naturalistic about the aesthetics of the ’70s.

I started doing pastels in seventh grade. I took art classes and I really loved the practice.

Avery: Where are you from? And how did growing up in that environment shape who you are?

Richard: I am from Chicago. I grew up in the suburbs ’till I was 12 and my parents had separated then divorced. I moved with my mother to the city and that was a huge shift in my development as a person. It took me from a more isolated upbringing and plopped me right in the middle of downtown Chicago. I also think that being gay—when I started to realize I was different, which was pretty young—really informed my identity. I felt, for most of the first part of my life, that I was different from everyone else, and I thought there was maybe something wrong with me. That experience really colored my view of the world.

When I moved to the city I found new wave music, alternative music, and punk. I found a kind of home within that difference and the sort of superficial manifestation of how I projected myself through funky haircuts, the music I listened to, and the clothes I wore. That was really important, that I was able to distinguish myself from the norm, because I already felt [outside of the norm] as a queer kid. Instead of hiding that, I found a way to actually celebrate it. Even though I had conflicting feelings about the level of comfort I felt with how I was seeing myself in relation to the rest of society, and that I was different, I was also into the difference. When I found photography, that gave me confidence. I think that, for instance, sports gave a lot of young kids a sense of self-worth. And I didn’t find that until I really found out about photography.

Avery: What do you look for in an environment when photographing?

Richard: Well, for environmental portraits, I always think about background, color, shape, geometry, lines, coincidence, serendipity, and text. I try to think about everything that’s happening around the subject. I look for simplicity, or an embrace of the dizziness that’s there. Texture is really important. I think I’m good at identifying and utilizing those things. Not always, of course, sometimes it falls flat, but it definitely feels like I’ve expanded my capabilities with that—especially with touching strangers, where I was [previously] thinking about these pairings in front of isolated backgrounds.

Avery: I know you have a body of work focused on Pier 45. Could you talk a little bit about the location and why it’s meaningful to you?

Richard: Yeah! I’ve lived in the West Village since 1993 and I’ve been in New York since ’86. I knew about the Christopher Street piers, but when I moved to the West Village I started hanging out there. And in the early ’90s, you know, there’s a whole gay history over here along Christopher Street and the West Side piers, and I kind of fell into the middle years of that history—living in this neighborhood, going out to the piers, and immediately inserting myself into the community of the people that hung out there. Not only going there to hang out, but going there to like sunbathe, going there to read, going there to meet friends, going there to look for sex, like cruising, and then going there to watch the Voguing kids. They’re still going out there in sort of different incarnations. Now, there’s a Black Trans Lives Matter weekly event on Thursdays that actually has been going on since the pandemic.

It’s really an important space to me. It’s also on the edge of the city, so it’s metaphorical. This community of queer people hang out here and form this sort of safe space, because a lot of them come from poor minority communities, or have been dishonored or just kicked out of their families for being queer. So they form these surrogate families and the piers are like—not where they live but where, a lot of the time, they hang out. I felt like I was on the periphery of that world. So I started photographing there, and seriously photographing there from, like, ’93 to ’98, and I tried to publish my first book of that work. Every publisher I went to in New York City said no and I put it away. Then I made a multimedia presentation years later, and I went back and started photographing there again.

Now I photograph there every couple of years. I have, like, almost an overview of the space, since before it was turned into the Hudson River Park, from the early ’90s, all the way to today. I’m there as both an observer and a participant, and there’s almost no other project [of mine], besides Manhattan Sunday, which I feel that way about, where I was kind of documenting a part of my world.

Avery: You’ve done so much work documenting social dynamics in the city, can you speak on how the city has changed over the span of your career?

Richard: It’s changed a lot. In some ways it’s the same, but I think it’s changed over the years in that real estate has become much more valuable. So access has kind of shifted and moved around—who gets to be where, and who has certain privileges as opposed to who doesn’t. In particular, speaking about the kids of the piers, they used to go out there in the ’90s and set up big boom boxes, and sometimes a drum set, and they would dance, sashay and shante until the sun went down on the weekends. All of a sudden, in the mid 2000s, the police stopped them from doing that. Then they had elegant tango dancing. That was sanctioned by the Hudson River Park Trust for more bourgeois or middle class people. So the kids, in a way, got pushed to the side. But they have kept their footing in this area and since, like, last year—or since the Black Lives Matter and George Floyd protests—they have really kind of asserted an ownership over Pier 40, which is right next to it. They have weekly dance parties there now, and you can hear the music echoing off the buildings. So there’s a reclamation happening.

I think that’s happening all over the city. I’ve noticed a big shift this year. Washington Square Park—I’ve never seen it like that. I’ve been going there since I was a student at NYU, and I’ve never seen the park being so completely owned, in essence, by the people. But, aesthetically, the city looks so different from when I was a young person here. It feels almost like it’s not my city anymore. I don’t recognize half of the buildings on the skyline, they go up so fast. I feel like there’s kind of a tension between what’s high off the ground and what’s low. You know, the wealthy people live up there, up high. And so the city has become more stratified. That’s one major change.

Avery: When you travel to make work, what does that process look like?

Richard: When I’m traveling, there’s the question of, what is my relationship to the place? Am I an outsider here? And what is my relationship to the subject that I’m making work about? I think I’ve started asking those questions even more, in regards to my own license and authority over subjects. I went through a lot of photographing on another continent to come to the conclusion that it wasn’t my place to tell the story of that continent. I feel like I arrived at the right conclusion. With photographing the United States, there’s lots of layers. Part of me sees myself as, ‘I am an American, and this is my country where I grew up,’ but I also see myself as a human being and not just an Earthling. So what right do I have to make work on Planet Earth? What right do I have to make work in the United States? What right do I have to create work in Fall River, where I’m not from? Do I only have the right to make work of my own class? Or my own race? These are interesting and important questions.

Avery: What stories are you trying to tell about the communities that you photograph? Ethically speaking, what do you think a photographer owes their subject, if anything?

Richard: Just to see them as an equal. If you start from that, that’s a pretty good starting point.

I think the stories I’m trying to tell often have to do with class. I don’t think they have too much to do with identity, that’s not my primary concern. But intimacy, I think, is something I’m really interested in, and a story that I’ve been exploring for a long time in my work. I’m also trying to find a way to make the stories I tell to be relevant to my own story yet connected to other people’s experiences in life. That is really important, to be able to bridge those two things, you know? You can go really deep, internally, into your own psyche, and make work that is about a lived or experienced trauma or something in your life. And that’s great, especially if it’s somehow cathartic and [gets] you thinking and feeling. But I think that, if you’re going to share it with the world, it is helpful if there are points in that work that people can access, and connect their story to that struggle. That’s something I try to figure out. Hopefully, my work is engaging in that way.

Avery: Has a friendship or collaborative relationship ever formed between yourself and a stranger that you have photographed?

Richard: Yeah, with my Manhattan Sunday series, I have formed friendships with people from the nightclubs that I photographed. One of my good friends, Ken Burnett, I photographed for Manhattan Sunday. That’s how I met him. The picture is actually not in the book, it got edited out. But we became good friends.

Avery: What is your greatest hope for a photograph you take and what is your worst fear?

Richard: Well my worst fear is, if it’s a piece of film, that it gets damaged. That’s not very deep—I mean, if it’s a crappy picture, who cares? It should never be seen, or [should] just go in the garbage, not a big deal. My hope is that it’s a good picture. I think it’s a little bit of a myth that photography—or art, or anything—has the power to change the world. Hopefully, photographs, as much as text or art, can illuminate. I think that works really beautifully with the concept of a photograph, because it’s about light. But as a metaphor, I think that could be great. If a picture can illuminate something for someone, that’s lovely. I don’t think you need to ask for world peace from a photograph. That ain’t gonna happen. But somehow, you know, inspire, illuminate. I think there’s an interesting contrast between a single image and a body of work doing that. They function both similarly and differently, which, I think, is kind of an interesting conversation, too.