As Simone Biles becomes the most decorated athlete in sports, Nkosi tells Document about the implications of Black girls' success in elite gymnastics, which has historically been used as a tool of oppression.

When Simone Biles made history at the 2019 World Championships by becoming the most decorated gymnast of any gender, she single-handedly redefined one of the world’s most elite sports. As a Black woman in a traditionally white space, she surpassed all expectations, becoming an icon in the process.

For Johannesburg-based multimedia artist Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, Biles’ success is a testament to Black power in the face of an establishment determined to undermine it. Earlier this summer Biles invented new skills and the Federation Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG), the sport’s governing body, penalized her for the groundbreaking performance. The FIG reduced the degree of Biles’ signature ‘double double’ dismount (two twists, two flips) from the beam—out of concern, they claimed, about the safety of lesser gymnasts who might harm themselves while attempting it.

“That felt so personal,” Nkosi says. “Simone Biles is flying and they have to find ways to hem her in. It’s like so many moments in my own life. Throughout my artistic career, people would say things like, ‘Oh, you will never be William Kentridge.’” The ill-fitting comparison to a third-generation South African man of Lithuanian-Jewish heritage smacks of misogynoir and is just one of the various ways people have tried to undermine Nkosi’s extraordinary life. But now, with the success of her new series Gymnasium, the artist is having her moment—just like Biles.

Born in New York to a South African father in exile and a Greek-American mother, Nkosi’s family moved to Harare, Zimbabwe, in 1989 when she just was eight years old. “I get this rush of emotion when I think of the day we were watching Nelson Mandela being released from prison in 1990 on TV,” Nkosi says. “My parents were looking at each other like, ‘This is it, we are going to go.’”

The family finally returned to South Africa in 1992 and Nkosi spent her adolescence living in a formerly white suburb of Johannesburg. “I was an alien, as I had been in Zimbabwe, as a kid of parents from mixed heritage. I was hyper-politicized very early because I was trying to navigate this racist space of my school and suburbs,” she remembers. “But then, on the other hand, I was in this exciting moment in Johannesburg: this explosion of music, clubs, radio stations, people doing their things. I was 14, 15, hanging out with my older brother who was in his 20s, and witnessing artists and filmmakers finding their voices and shouting them loud.”

Nkosi returned to the United States to obtain her BA from Harvard University before moving back to Harlem to pursue her MFA from the School of Visual Arts. “A fatigue about speaking about my mixed race family had set in during my teen years, and I decided that if I went back to the U.S., I would have more freedom,” Nkosi says.

She found her footing in New York in a community that included Africans and first-generation Americans from all around the globe. But at the same time, Nkosi was witnessing the massive gentrification project that swept across Harlem in the late ‘00s. During her valedictorian speech, Nkosi spoke of the South African owner of a record shop on 125th Street who was being forced out of the neighborhood after 40 years. It was an eerily familiar story.

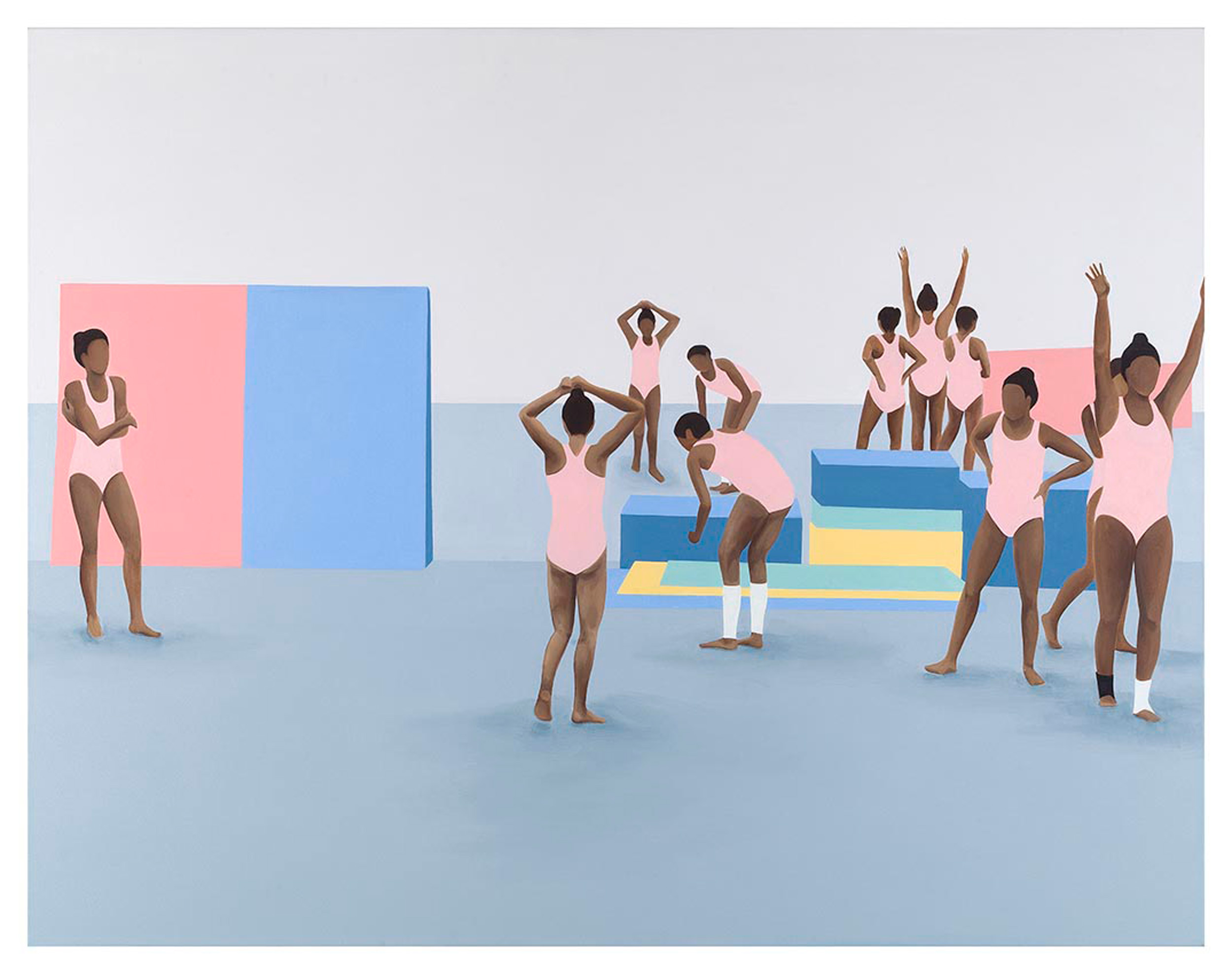

The sense of space has long informed Nkosi’s work, perhaps drawn from a desire to find a place to call her own. The Gymnasium series began as outgrowth of earlier architectural paintings examining the symbolic vestiges of apartheid in Johannesburg, in recognition that “nothing much had changed.” While doing a Google Image search in 2012, Nkosi came upon a photograph of a gymnasium and painted it, deciding to recast the little white girls in the picture as brown.

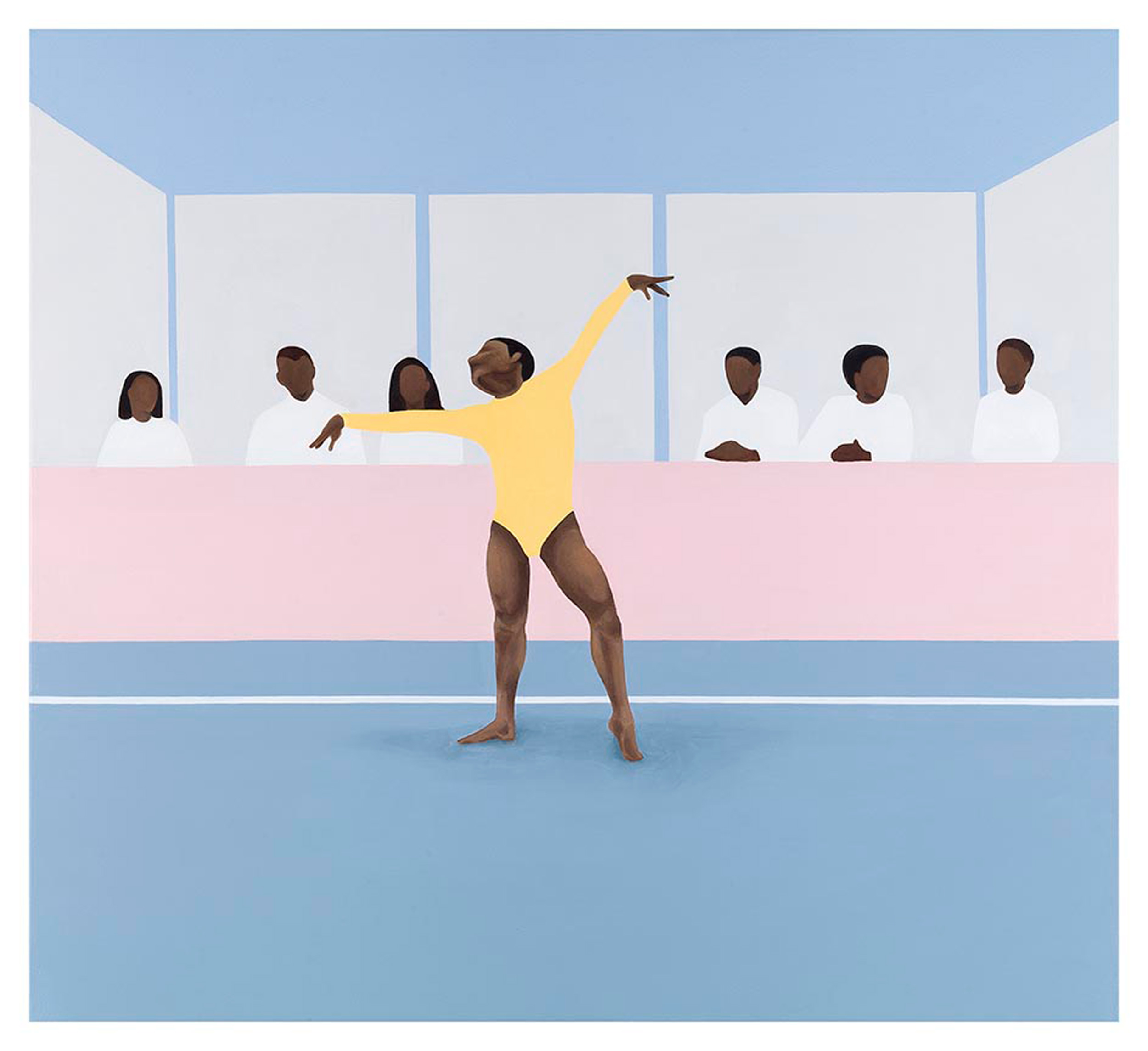

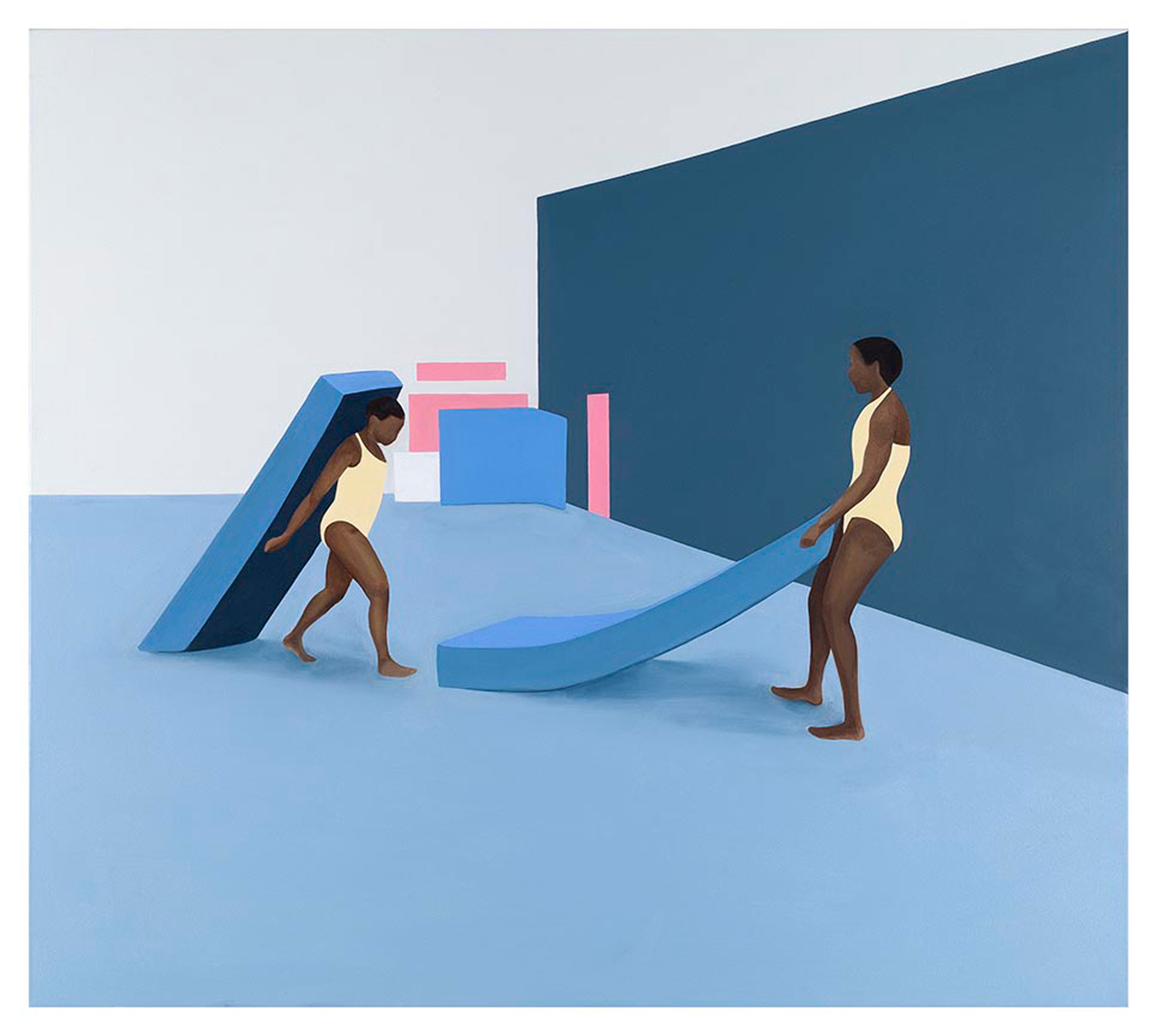

“Something was planted in my psyche somewhere,” Nkosi reveals. Earlier this year she returned to the series with a new relationship to the work. “The metaphor for the world of gymnastics suddenly emerged for me. It is a performance: having to perform your identity as an artist, and a Black artist. It is judgment being witnessed, failing, succeeding, and being highly visible. All these things translated really well into an experience I was having at this moment. My career is starting to move and I am questioning how I am performing in public. At the same time in gymnastics, this is a Black women’s and girls moment.”

Eager to learn more, Nkosi began to research the history of gymnastics. She discovered a Danish gymnast and educator named Niels Bukh (1880-1950) who developed a system of exercise that became popular in Germany. In 1933, he expressed his allegiance to Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist Party, and began traveling the world, leading a campaign that promulgated gymnastics as a vehicle for white supremacy.

“I was interested in the history of the sport as a tool for propaganda, colonization, and white supremacy. Bukh came to South Africa in the late ‘30s and was telling the white pre-apartheid government officials and population that they needed to do athletic work because the Black natives will become strong and eventually overpower them,” Nkosi says.

“The sport promotes the idea of the perfect person, the ubermensch — never imagining Simone Biles and Gabby Douglas would dominate the field and become the image of athletic perfection and superhuman ability, taking the sport to places it has never been. In New York, I saw t-shirts that said, ‘I am my ancestors’ wildest dreams,’ and I kept thinking about this about the sport.”

Nkosi refrains from giving her gymnasts and judges identifiable features, so that they become stand-ins for anyone who wishes to imagine themselves in the scene. “When I paint figures in this series, it’s not about the individual. The gymnast doesn’t have to be a star; she is important no matter who she is. There is power in not being specific and not being special,” Nkosi says.

“At the Africa Center, the best moments were when young girls of color came in and saw themselves in the work. Seeing yourself in the world, pop culture, and art is so powerful for us. I saw myself in those little girls and it was deeply moving for me. As an artist, when you make something, you want your intentions and message to be seen—you want to be seen and felt.”

‘Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi: Gymnasium’ is on view at The Africa Center in New York through January 5, 2020.