Pat Ivers and Emily Armstrong tell us how they filmed at punk's most outrageous venues while surviving off gallery wine and cheese.

Nearly every night between the mid ’70s and early ’80s—sometimes more than once—Pat Ivers and Emily Armstrong lugged television video cameras and lighting equipment around Lower Manhattan. They caught hundreds of performances from bands who defined the era: think Dead Boys, Talking Heads, Blondie, Richard Hell, Bad Brains. Pat and Emily’s films became underground treasures, cherished by the bands they shot and the scene kids who crowded into neighborhood bars to watch ‘Nightclubbing,’ their cable access show. Between shoots, CBGB’s owner Hilly Kristal clumsily set up them up with dates, a Dead Kennedy crashed on Pat’s couch, and they spent a night in jail with Keith Haring and David Wojnarowicz.

In a four-part series for Document, Pat and Emily trace the origins of their “spiritual following”: to capture the fleeting moment in New York music when rent was $60 and Iggy Pop was two feet away. Over the next weeks, the pair will be taking us through the bands and venues that best capture the inimitable energy that was early-days punk.

For their first edition, Pat and Emily take us through their humble beginnings—and why Andrew Yang might be onto something with universal basic income.

Pat Ivers—We met at Manhattan Cable. We were both working in public access. Emily would book all of the crazy public access producers that would come in every day, and I would work with them to make their insane shows. I had already been shooting bands at that point; I started with the unsigned bands festival in August of 1975. I was shooting with a bunch of guys up until then, and they didn’t want to continue. So, I met Emily.

Emily Armstrong—I had horrible jobs. One night, I had to sit in the electrical panel room and every time one of the switches flipped over, I flipped it back. Like, that was my job.

Pat—For hours.

Emily—[Laughs] I didn’t have the highest jobs that’s for sure, but we were familiar with the equipment. That was really, I think, the key to our success. We had access to it, and we knew how to use it.

Pat—Once I started [filming], I didn’t want to stop because I could see that it was an ephemeral moment. This was something that was electric, and it wasn’t gonna last. It was a moment in time. It was this focus of energy. To document it seemed to me almost like a spiritual following. CBGB’s was the home of DIY, and so everybody did something. I couldn’t really play any instruments. I was too shy to sing. So, my contribution was doing video.

Emily—We would give the bands a copy of their performances as often as we could, and that really something special. And then when we had our cable TV show, they would get shown on television which was unheard of back then. We came right in at the moment before portable VHS cameras. And we were very careful with our sound. CB’s did a separate mix so most of our stuff from CB’s has really remarkably good sound for that time period. The people in CB’s were our friends; they were our neighbors. We lived around the corner. So it was also like our local bar. If I wanted to have a beer, I could just go there. [Laughs]

Emily—We’re also women, and we were the only people doing it, and we were two girls in high heels and punk clothes. We were pretty distinctive looking. I don’t think I realized at the time how unusual it was.

Pat—But one of the really fabulous things about the punk scene was it was, for my experience, incredibly nonsexist. No one hassled you about trying to do something because you’re a woman.

Emily—Yeah, never.

Pat—It was really after the punk scene that started to happen. I was shocked because we never experience it, you know, among our people. [Laughs] It like once the record company steps up, stuff like that, then you came up against it, but our people? No.

Emily—And even if we went into a different club in a different town or in town, most of the time, the people working there were 100 percent down with us being there and working with us and helping us get the lighting and good sound. We had to get there before the club opened and leave after the club pretty much closed because we had this mountain of equipment; we were really friends with the staff more.

Pat—It’s kinda hard to communicate how heavy the equipment was back then and how much of it there was to do anything. It was just enormous. And it’s also hard to communicate how limited the offerings were on TV. The idea of seeing a band from downtown on TV, it was astounding.

Emily—It was pre-MTV.

Pat—Yeah, MTV started like ’81. So, you know?

Emily—We worked in cable television so we knew it was coming, but it was so not there yet. I mean, the early days of cable New York, what was happening in New York was only happening in, like, a handful of other cities where they really had local access and they were literally wiring up the city building by building. Like digging holes and wiring up individual buildings. It was really Cowboys and Indians.

Pat—It took us years before we even got it in our building. We would have to go to, there was a bar called Paul’s Lounge on 11th Street and 3rd Avenue, and once we started doing our show Nightclubbing, that’s where people would go to watch it. You know, most people didn’t have cable downtown.

They wired the Upper East Side. They wired the Upper West Side. But Lower Manhattan, Lower East Side, are you kidding me?

Emily—We were off Houston Street like down Orchard like one, two, three buildings down. We were last because there was not a lot of income there. And probably a lot of people who would default on their bills and stuff.

Pat—You know, Lower East Side, the cops wouldn’t come; the Fire Department would barely come.

Emily—The garbage would be picked up really erratically back then in the late ’70s.

Pat—Again, it’s hard to communicate how much of an island—

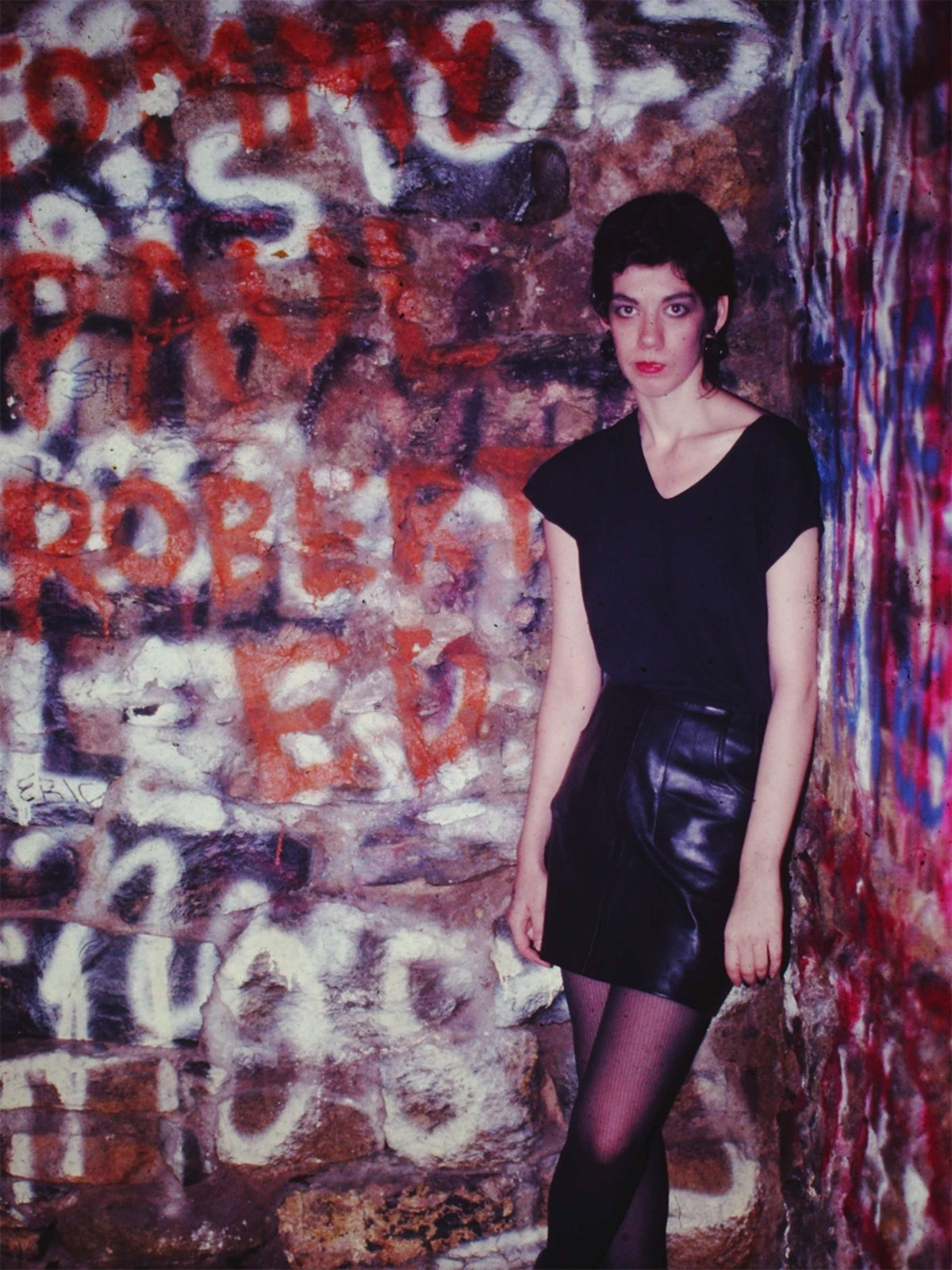

Emily—You see these pictures of these abandoned lots. Every single wall is graffiti. It was really like that. That’s not just one brand of picture they picked out. It was really like that. You could walk for blocks and it would look like that. And you wouldn’t walk. I was afraid to walk down Avenue A. I stuck to 1st Avenue, 2nd Avenue. But, you know, because the Lower Side was such a nasty place, apartments were really, really cheap. My first apartment was $66 a month. When I moved to Orchard Street—because I met my boyfriend then, my husband now—he lived on Orchard Street in this building that had been renovated in the ’20s, so it had, like, real bathrooms and stuff like that. I remember fretting it and thinking ‘how am I going to pay $140 in rent.’

Everybody we knew had cheap apartments. People lived in crazy industrial buildings with one sink. It was amazing. People didn’t have to work so much. You could have a part-time job. Bands had rehearsal spaces, reasonably priced.

Pat—It’s a real argument for the annual wage that [Andrew] Yang is talking about. It gives people a chance to be creative. [Laughs]

Emily—And everybody was super skinny cause we couldn’t even have that much food. [Laughs] We had some things but not a lot of things.

Pat—We walked everywhere.

Emily—Being a young person now, dealing with these really high rents and stuff, we didn’t have that problem. And we would go to, like, art openings to get free wine and eat cheese and stuff like that. There used to be this Irish place on 23rd Street that had these steamer trays out in the middle of the room. There’d be free hors d’oeuvres. I ran happy hour. It’d be, like bad meatballs and stuff. I was talking about that with my husband: ‘That would be my dinner.’ Things were cheaper and as a result, life was cheaper. You were just out there.

Read the all editions of the series here.

View the entire ‘Nightclubbing’ archive at the Fales Library and Special Collections.