The textile artist explores black queer identity in his stunning, Southwestern tapestries.

Textile art is experiencing a new kind of popularity right now. There are queer knitting circles, sexually graphic embrodiery, and retrospectives on home fabric designers at The Met. But before this millennial-flavored shift, textile art was rarely featured in contemporary art spaces. Weaving was, unfairly, seen by many as simply a “craft,” not a serious practice. More Hobby Lobby than Guggenheim. How fitting, then, that a queer black artist from Texas has found refuge in this long neglected and misunderstood art form.

“I remember walking into my first fabrics class at the University of North Texas and there was this giant cabinet of color-coded yarn. It looked like the rainbow,” Diedrick Brackens tells Document. “I didn’t know what weaving was really—but I was attracted to the imagery.”

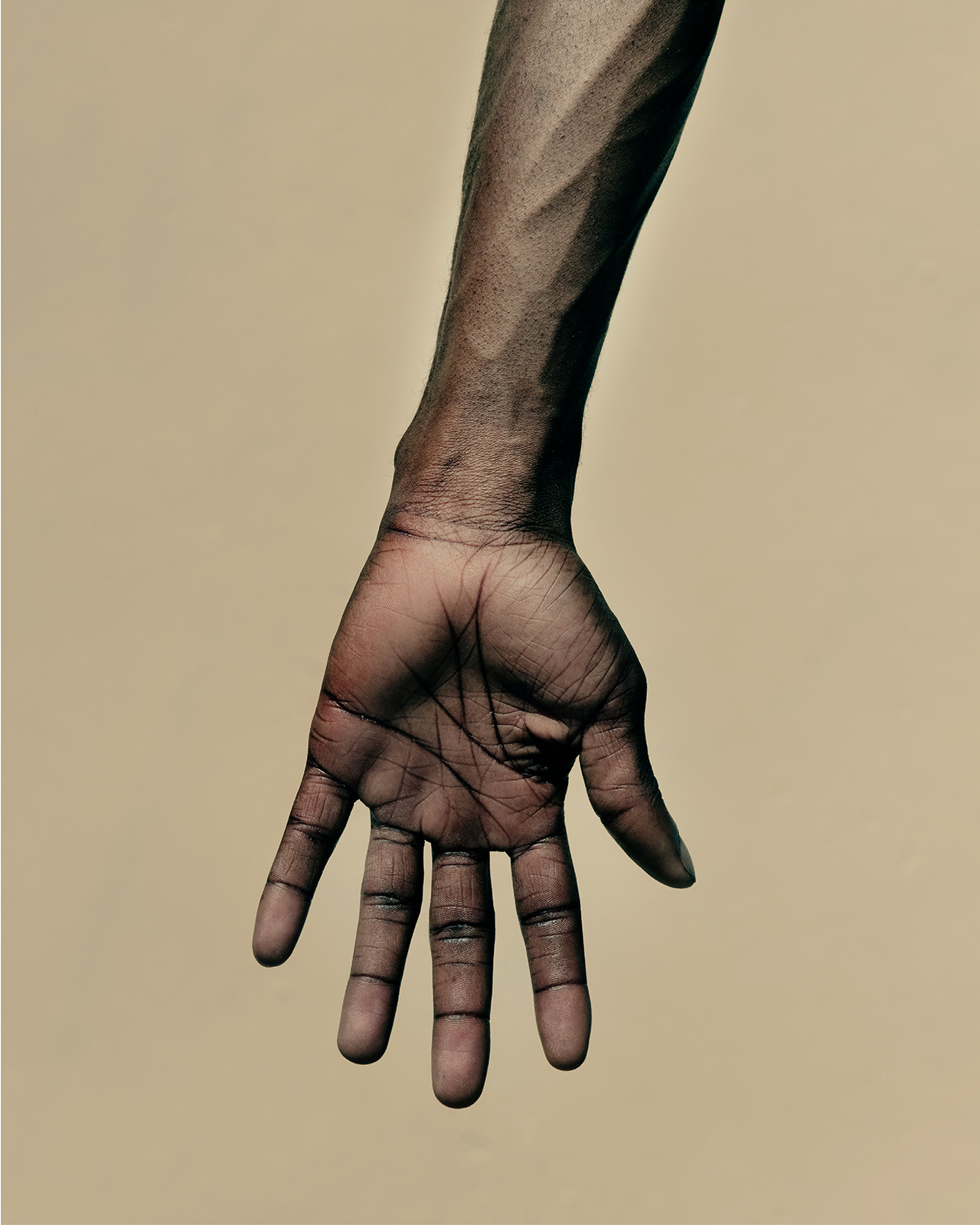

Diedrick walks Document through his first major solo exhibition, darling divined (on view at the New Museum through September 8). The space is awash in color, from hushed pinks to sunset golds to electric greens. The 30-year-old artist weaves scenes reminiscent of folkloric tales and fables. Two men greet a sheep in the desert, the night sky behind them an intense, charged-up shade of purple. In another, two men fish in a lake, one of them holding a catfish of biblical proportions. There’s a running thread here: Black men. Both alone and together. Diedrick says he wanted to investigate the relationships that exist between us. “What does it mean to be tender as a man?” he asks. “Or violent? Or embraced?”

Personal narratives are woven into everything Diedrick makes. A scene is never just a scene for him. A barking dog symbolizes unfettered rage and police brutality. Cobalt blues evoke thunder and lightning. We land on Diedrick’s depiction of men fishing for catfish (titled “bitter attendance drown jubilee”). At first glance, with its golden backdrop and 3D materials, the work feels like an ebullient depiction of a summer day. But as Diedrick talks about the piece, he reveals the scene has a deeper, darker meaning.

Diedrick was reflecting on his hometown’s massive Juneteenth celebrations while weaving the catfish in the scene. In 1981, three black boys were caught by police smoking marijuana at the gathering and handcuffed and put on a boat. As the police transported the suspects across the lake, to be properly apprehended, the boat capsized. All three boys drowned. Meanwhile, the four cops either swam to safety or were rescued.

“The fish represent those lives lost,” Diedrick says, taking in the three catfish with profound sobriety. Then he highlights the handcuffs floating at the bottom of the lake. The very things that kept the boys from swimming and living. Much like all things in the south, this scene of prosperity and wealth is built off a long history of racial inequality. “Before that, the Juneteenth celebrations in [the Texas city of] Mexia would draw in like 20,000 people. People who came from everywhere. After this happened,” Diedrick says, pointing at his tapestry, “they were lucky if a thousand people came.”

But Diedrick is steadfast about assuming his work with a powerful sense of optimism. Perhaps that is because, as queer black men, optimism is one of the few tools avaliable to us. The driving belief that things can, and will, get better. That’s why he chose to have gold tones overpower the scene. “It represents purity, light, luxury, and hopefulness,” Diedrick, a self-described color theory geek, explains. “It can represent the space between sunrise and sunset.” The color of change, of time passing. “If auras exist, yellow is definitely the color of mine.”