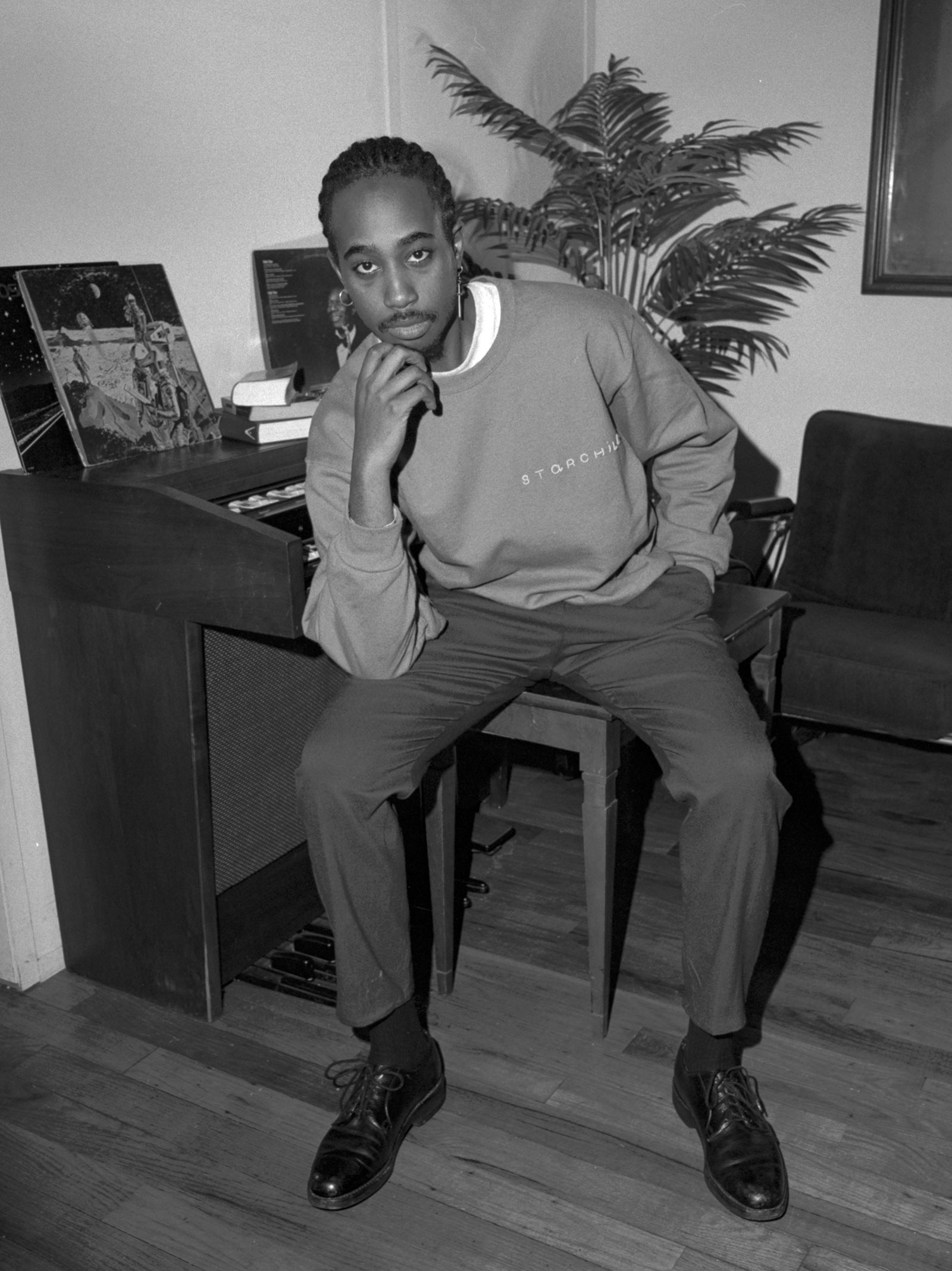

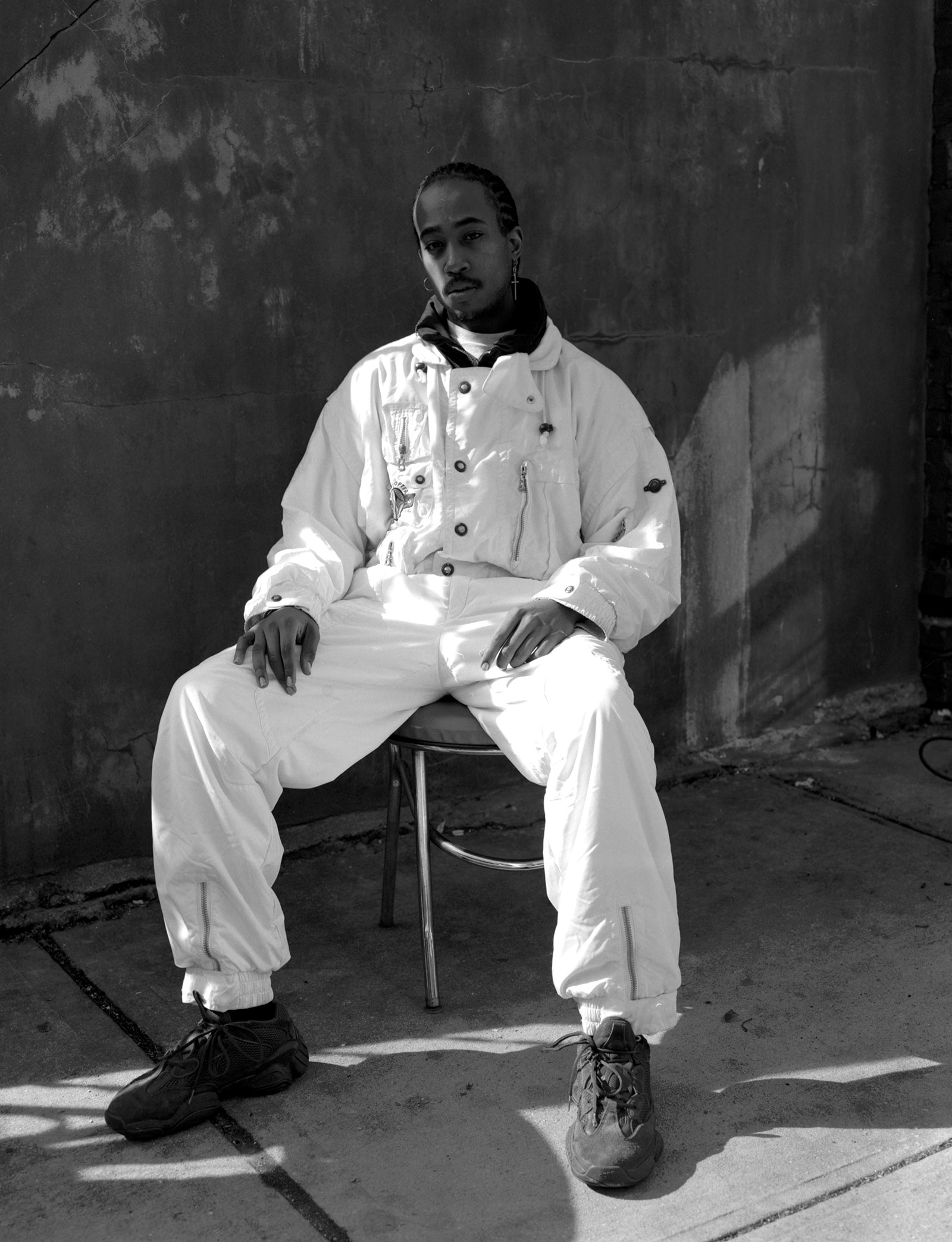

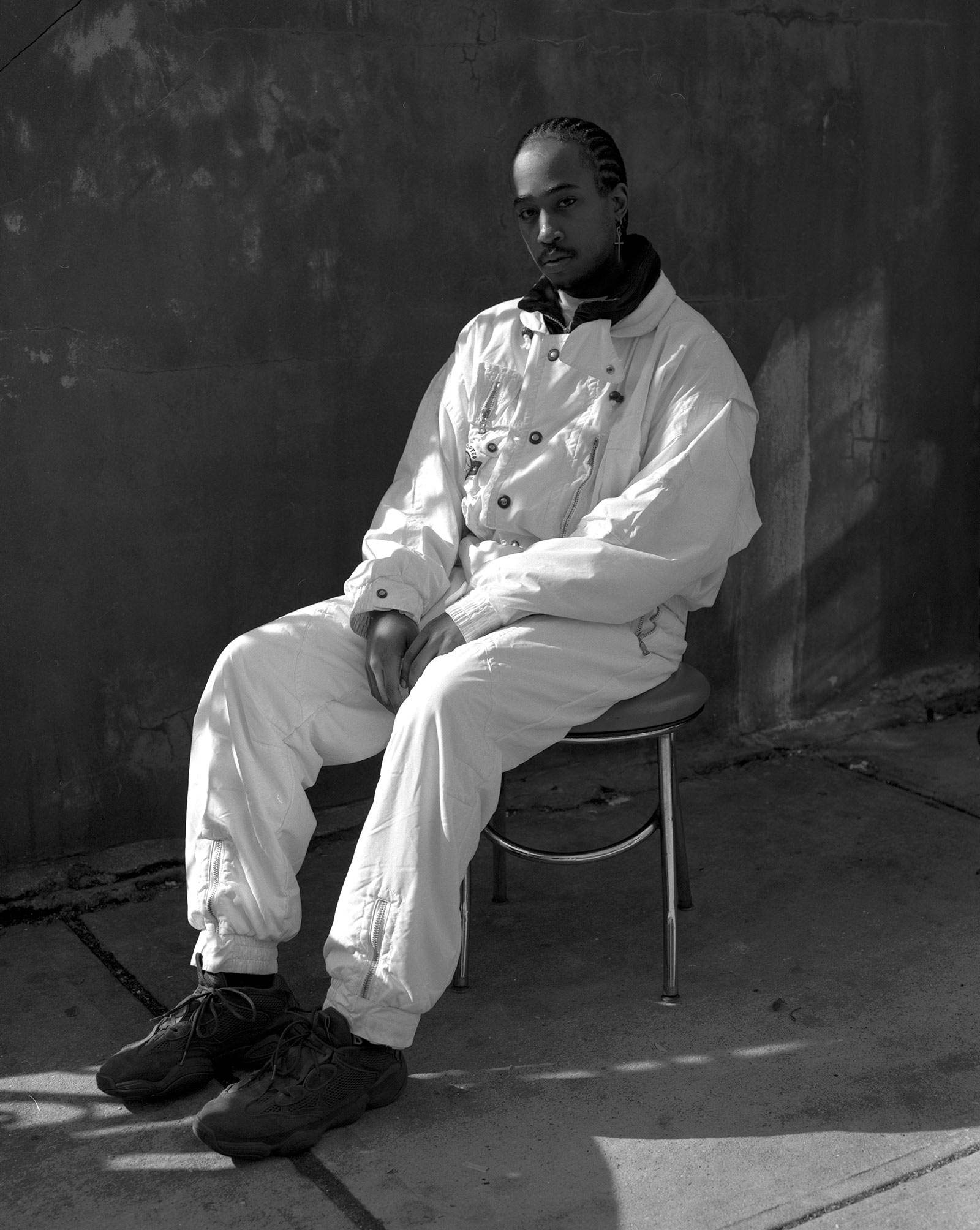

Ahead of his new album, Bryndon Cook—a.k.a. Starchild and the New Romantic— discusses southern identity and strong women with photographer Rahim Fortune.

Moving from the South to New York City presents one with a number of challenges, some immediate and others encountered as you go along. After moving up from Kentucky, I found myself burdened with numerous questions: Why do people here enunciate every syllable when they speak? Should you refer to people as sir and ma’am? Where is the sweet tea? And most pressing, how do you balance the new mannerisms you have adopted with what is expected of you back home?

Document sat down with artists Rahim Fortune and Bryndon Cook to discuss what it has meant for them to move North while maintaining the better parts of their Southern roots. Fortune is a photographer and visual artist who split time between Texas and Oklahoma growing up. His commitment to community and gentle refusal to be boxed in struck me, and I have been thinking about many of his words since this conversation. Cook makes music under the name Starchild and the New Romantic. He gives Document a teaser for his upcoming album Forever, reflects on the impact his family has had on his musical career, and demonstrates a visible desire to occupy all parts of himself. Here, Fortune and Cook shared their many musical references and the roles women have played in shaping who they are today.

Above The Fold

An Olfactory Memory Inspires Jason Wu’s First Fragrance

Archetypes Redefined: Backstage London Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Dematerialization: “Escape Attempts” at Shulamit Nazarian

Bringing the House Down

Rahim Fortune—So your father is originally from Mississippi?

Bryndon Cook—He’s from a small town called Magnolia and my mother is from the other side of the tracks in Magnolia. It’s, like, an hour out of Jackson, and they’re the first in their families, for college in particular, to go to an Ivy League and leave the state. [My brothers and I] are the first of our family to be born out of Mississippi.

Rahim—Wow, that’s incredible. My grandfather is originally from Tampa, and his father was the first Black dentist in Tampa. My grandfather was one of the first Black male instructors at West Point. His whole side of the family has got a lot of that Black excellence. It’s really interesting to hear the intersections of both of our family histories… Growing up in D.C. when was one of your first memories of traveling back to Mississippi and what was that like?

Bryndon—Every summer I can remember, we would drive down from Maryland to Mississippi, which is, like, a 15-hour drive. We wouldn’t usually stop, so I have these memories of [us] three boys falling asleep in the Camry… I remember waking up in the middle of the night and my dad listening to the Commodores, Anita Baker, Luther Vandross’ greatest hits… It wasn’t until we moved to Atlanta around 2000 when I, in fourth grade, started learning saxophone in school, and picking up guitar. Guitar was basically my bridge to funk.

Rahim—My father is a funk drummer. Him and my uncle play in a band called Dysfunkshun Junkshun. Some of my earliest memories are going to his concerts and the different things that he was playing in the car or making me sing harmonies to…Having my older brother, and this mix of early 2000s hip-hop—things like Dem Franchize Boys and Crime Mob, being caught between these two different worlds, but the setting of being in Texas and Oklahoma, which had its own implications. So it was always interesting—people not really being able to pin you down as one thing.

Bryndon—There’s this dual consciousness of Texas… the dichotomy between Mexican, Tex-Mex and the dirty, dirty South… You said nobody could really pin you down. What’s it like to find that [dual] identity amidst such a mix of cultures in Texas?

Rahim—You don’t really think about some of these things when you’re younger… but now that I look back, I was around a lot of Latin people, a lot of Hispanic people. There was always a really interesting cultural trade-off between Black and Hispanic communities—going to a friend’s house and learning a little bit of Spanish just so you could be able to talk to someone’s grandma enough to get a plate. Because if you ain’t talking to her she ain’t gonna feed you.

Bryndon—She ain’t gonna give you no arepas or nothing!

Rahim—It was also an example of the solidarity between the Chicano and the Black community, and their ability to recognize that they had a common goal politically.

Bryndon—Having split my childhood between Maryland and Atlanta, I would say that Maryland is the place that I didn’t really feel that I fit in… It’s very rural, and it’s got these red roots… [Atlanta] was this huge, Black, youthful surge of art that really gave me space to be, a point of departure that inspired my own music. I’m really grateful for that, having both experiences.

Rahim—Now that I’m creating visual art, a lot of the things that I’m interested in [are] rooted in this early way of how I came to see myself. A lot of the people I choose to make portraits of, or the people I choose to work with, are all coming from this shared experience that we might not have known we had until we began talking.

Bryndon—One of the things I really like about your work is seeing you capture people in such a natural way, but sometimes it’s people doing extraordinary things… I was wondering if your upbringing in these places that are so close to nature, and seeing people do extraordinary things in the day-to-day, informed the work that you do now?

Rahim—Obviously I’m interested in having people’s permission to tell their story or document them, but I’m not really interjecting too much into the story. Maybe I’ll get someone’s permission and let them settle back into what they were doing, and then make a photograph. I’m also very big on not overly photographing anything, so I might take one or two shots, and if I don’t get the photograph then I’ll just have that as a memory…

I really want to pick your brain a bit about the new record. I feel like there’s enjoying a friend’s music because it’s your friend’s music, and then there’s enjoying your friend’s music because it really slaps. That new album, I just want to know about how that came to be.

Bryndon—It’s my third record, right? I always try and do something that I haven’t done before. That’s, like, my blueprint, and I make that framework, and then I try and get free in it. So I produced it all myself, and I wrote it while I was on the last leg of the A Seat at the Table tour… I was traveling a lot. I think that’s when a lot of writing comes forward… [Forever] is [about] unconditional love, and trying to figure out what that really means. [I’m] talking about things that I had never really talked about—sexuality, stuff in my journey. I was trying to let it pour out, and I ended up having a mixtape and a record.

Allie Monck—Could you talk more about identity in terms of going home? How do you learn to have compassion in those areas too when you feel, ‘I know this thing and you don’t know this thing and I’m still trying to navigate this relationship’ when it feels so important?

Bryndon—For me, and this definitely pairs with what Rahim was talking about, [it’s] the influence of female energy and women in my life. The more I learn about my mother’s life and her journey, the more I’m imbued with the energy just to be able to be… to just step aside from the fight of it all—the fight to survive—which I think is such a part of New York and a part about being an adult.

Rahim—I recently read a book by Jean Toomer entitled Cane. That book is completely about gender and race in the American South in the 1920s… He talks about how people in the North tend to use more words. The culture in the South is a lot more non-verbal and it’s slower. People coming back from the North [can] miscommunicate with their surroundings and with people, and they’re a little bit quicker to brush off some of the tradition and some of the things that can be learned by simply watching. I think that that’s the way I view it. Obviously you try to stop any immediate violence, but not come back with this, “Alright let me come save these people.” Just sit back and let things work themselves out in that way.

Bryndon—So true.