The musician hones in on isolation in his new project ‘Bruteman,’ which traverses an album and accompanying photo book.

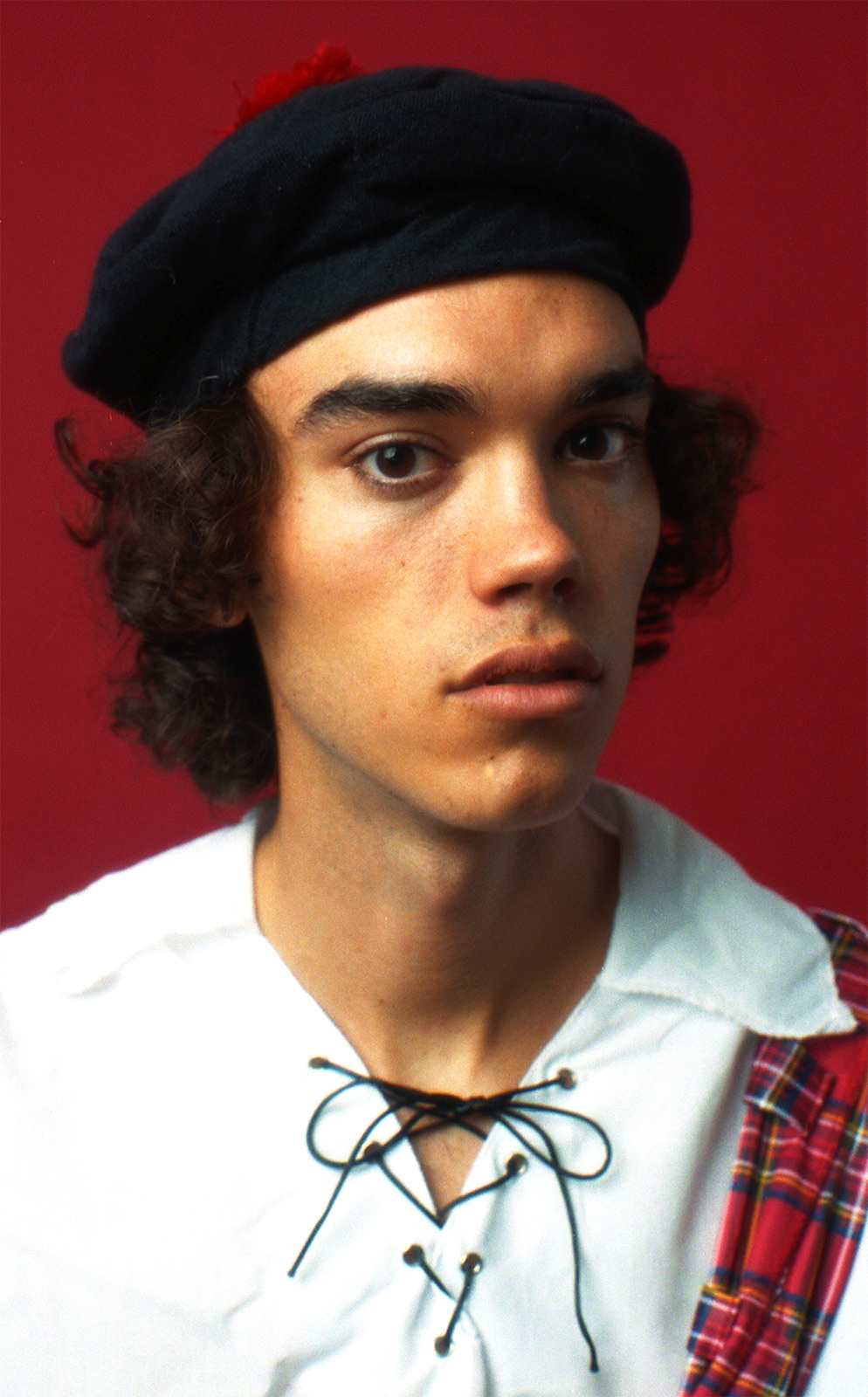

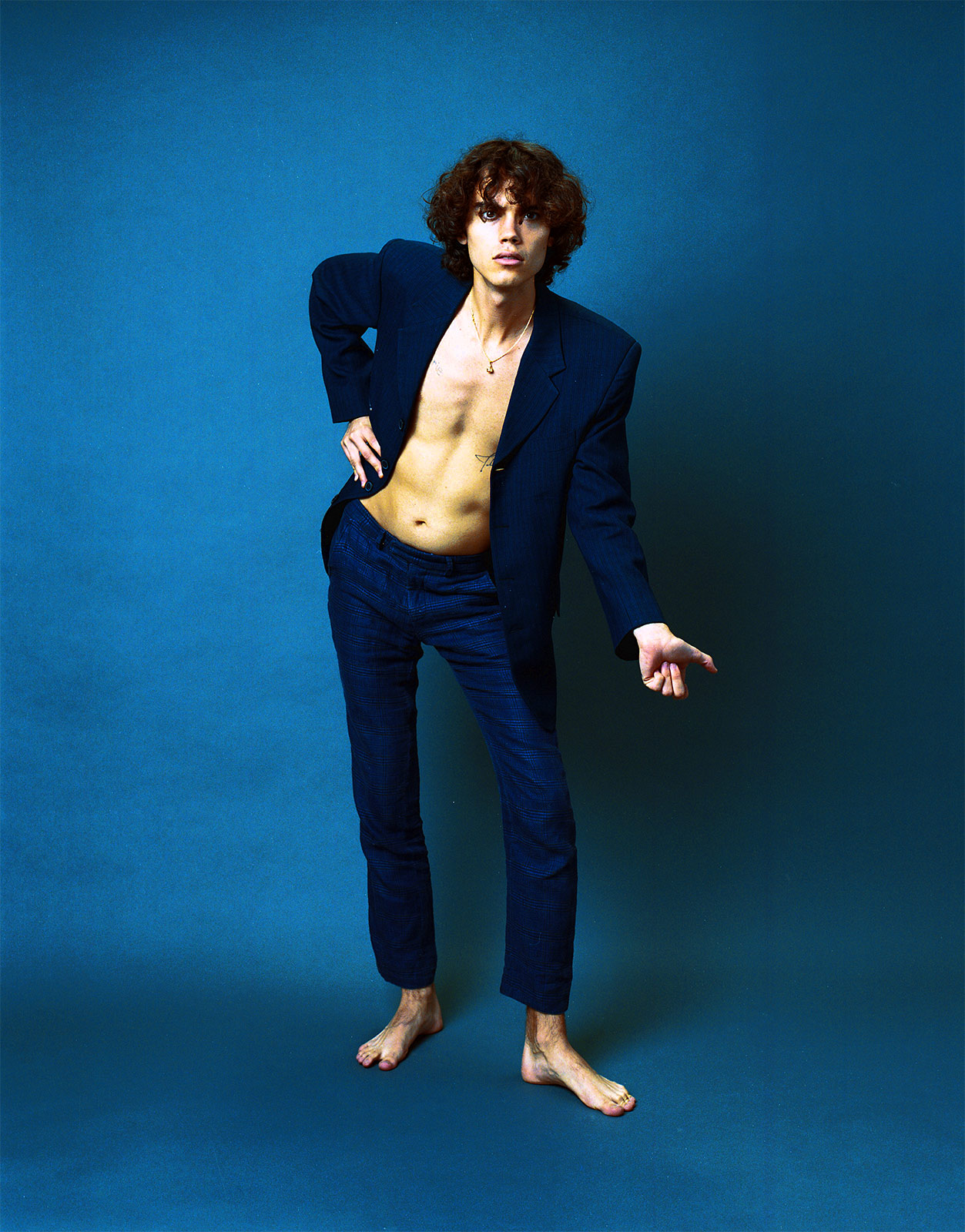

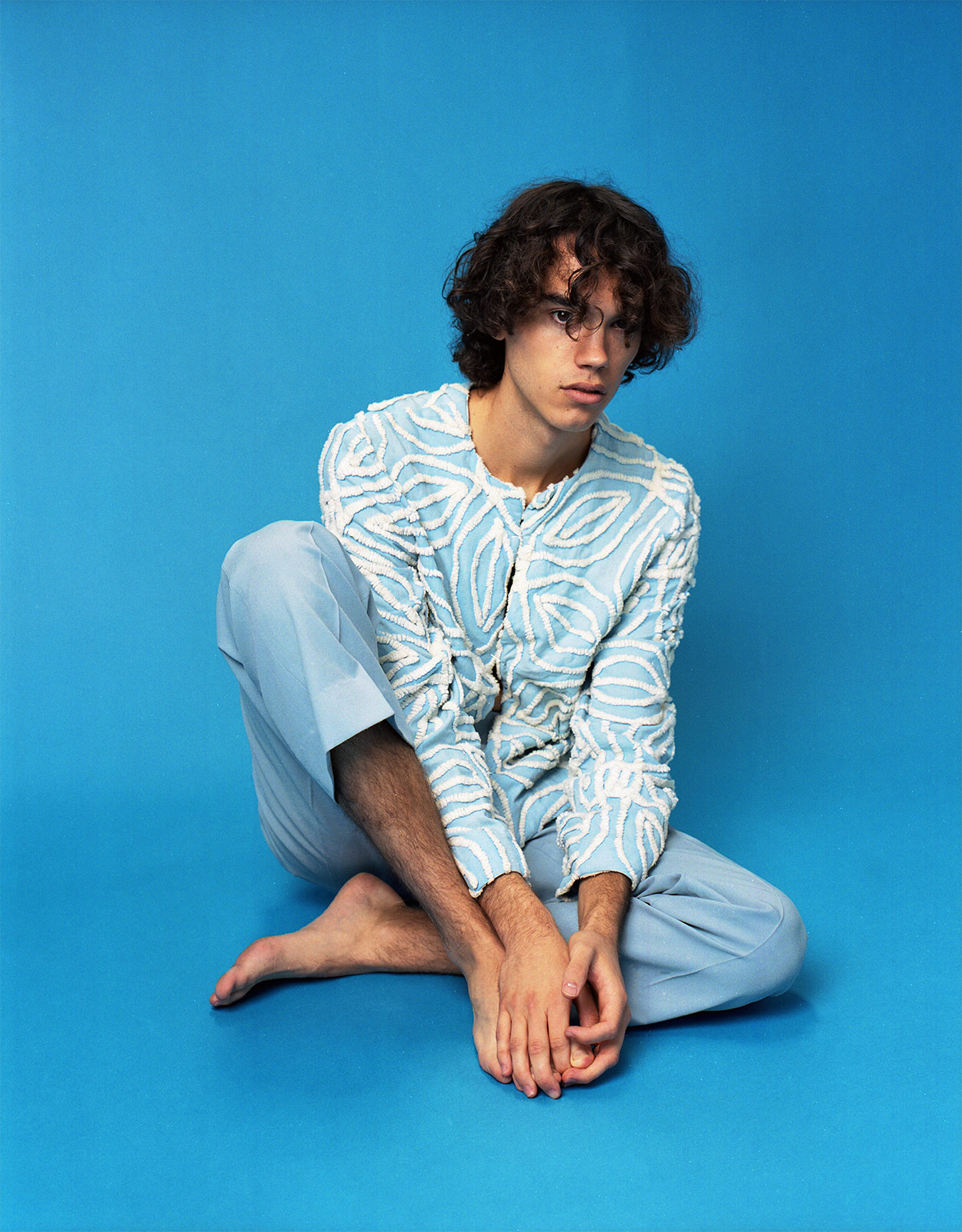

The Bruteman Book opens with a number of poignant phrases as a means of positioning itself alongside its partner, Bruteman the album. Its author, Max of Homestead, the alter ego Lazaro Rodriguez created to funnel his art through, states, “Time is better than money because it never inflates and can be spent anywhere.” He later interrupts the series of portraits, coordinated to represent each of the songs off the album, to assert “that every song on Bruteman was used as a coping mechanism for my solitude.” There is the set from “Gold Skin” in which he wears groovy printed trousers, a gold silk shirt, slicked back hair, and chunky gold glitter covers his face. The book serves as a proper accompaniment to an album exploring isolation, change, masculinity, and more.

Having produced all of Bruteman on his own, Max says that being self-taught came from “a necessity to stop being so reliant on others,” and found it shaping his sound. “I spent the better half of two years just learning production and figuring out how I can mesh that into the music I was already making,” he recalls. “It was just gradually helping me to progress into this new sound.”

Bruteman is a young man earnestly making sense of the passage from adolescence to adulthood. It’s not masked in metaphor upon metaphor, nor is it always linear. On the song “Gold Skin,” he repeatedly sings, “This is not what I thought this is not what I wanted,” before closing the song in an earnest beg to “Kiss that golden skin I know I have.”

The theme that appears most concretely in The Bruteman Book is masculinity. In 2017, Max wrote, directed, and edited The Ape, a four-part mockumentary working to unpack masculinity. In contrast to The Ape, Bruteman works to tackle “the more psychological effects of what this cloud of masculinity can hang like.” Max goes into further detail concerning his own experience. “I became aware of all of the negatives of masculinity, but I’m still a very confident person and I realize that I just have to own this shit,” he says. “There are other people who may have flirted with the ideas but they kind of let that shit rock because it’s not that important in their life. Then there are kids that really battle with this confusion of normality.”

Referencing a wide range of childhood influences including Kanye West, David Bowie, Freddie Mercury, and Todd Rundgren, Max of Homestead draws a level of confidence from men of the past who embraced butterfly eyelashes and sequined go-go suits and makeup. In a time where dissecting masculinity is a multi-generational act spanning every profession, it feels as though we have been clouded with a number of different visual interpretations of the feminine side of men as a means of reckoning. What I found energizing about the photos in The Bruteman Book, as well as in Max’s lyrical content, was the dedication to exploring one’s own masculinity before projecting it out. He reflects, “You’re supposed to be working for you, you are your biggest consumer… I don’t want to abide by anything, even if it’s this new wave of consciousness,” he says. “I just want to exist in my own world and that’s always going to come first over any type of awareness I get put on to.”

Max of Homestead has generated a body of conscious work. Dedicated to creating through organic processes, Max provides hope that more male artists pursue their work introspectively and with a heavy dose of vulnerability. After speaking with him, I found myself struck by someone who had visibly done the work of figuring himself out. He didn’t mind pausing to gather his thoughts, he refused to potentially invalidate the work of others, and he owned his work with earnest. Certainly not a brute, Max embodies the frontiers of selfhood.