As part of the Document Journal x Prada Mode conversation series at Art Basel in Miami Beach, we highlight six visionary artists changing the future of image making, and transporting us from untenable presents to unimagined futures.

Multi-disciplinary Egyptian-Lebanese artist Lara Baladi has been documenting the act of protesting and its discourse since she witnessed the Arab Spring firsthand. Her then-hometown of Cairo was the site of the 2011 Egyptian revolution and the mass protests in Tahrir Square, leading to the resignation of President Mubarak. Document spoke to Lara—a panelist on the talk “Public Access: Offline Media Dissemination” at Prada Mode at the Freehand Miami Beach on December 6—about her experience of documenting dissent and how digital media has changed the face of political uprisings.

Caroline Christie—Can you talk about the impact of some of the powerful imagery that came out of the Tahrir Square movement in 2011?

Lara Baladi—The image of the multitude in Tahrir Square, of people looking like ants from the sky, first impacted the Arab world. The unprecedented scale of the crowd and the sense of solidarity that transpired from this vibrant, powerful, bird’s eye view of Tahrir Square helped trigger more uprisings and protests— from Libya, Syria, and Bahrain to the many Occupy movements that followed. This iconic image was all over the media, if not full screen, it was always lurking in the corner above the news anchor. First and foremost, it inspired, worldwide, hope for a better future.

Arabs are almost always portrayed negatively by Western media. The bird’s eye view of Tahrir Square and the many more images of the Egyptian uprisings which went viral online, even if for a short moment, radically shifted this prejudiced image of Arabs. I remember when almost exactly at the same time as the uprisings started in Egypt, thousands of Americans were opposing the “Wisconsin Budget Repair Bill.” Protesters were holding banners with inscriptions that read “Egypt Help Us.” Americans then identified with people in Tahrir Square and saw their own struggle mirrored in the Egyptian uprisings. The Tunisian uprising woke the Arab world and Egypt’s Tahrir Square woke the rest of the world to the realization that we had become numbed in the face of political oppression and/or capitalism and that we needed to rise.

Caroline—How have you continued to look at the theme of protests in your work?

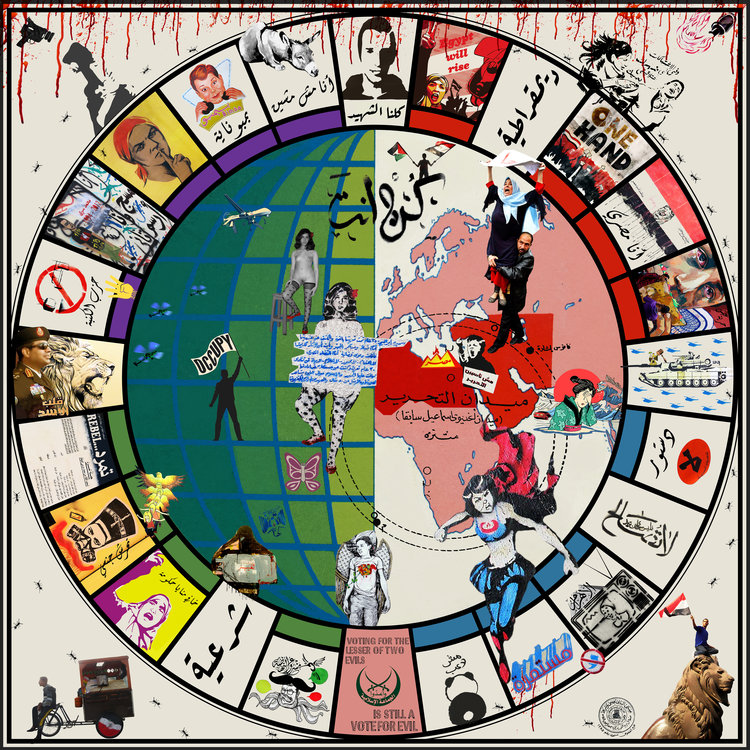

Lara—Since 2011, my work has been inspired by my experience in Tahrir Square, and has stemmed from an archive I have gathered and continue to gather on the Egyptian uprisings. Tahrir Square and the Arab uprisings at large are possibly the most documented events in history, with a vast amount of digital production disseminated online. I have been reflecting on this phenomena and working with the archive in many ways, from creating artworks to writing essays. Today, I am looking at the bigger picture, at how these events in Egypt resonate, across culture, time, and geography, with other, past and present, global social movements. In an attempt to display a narrative and draw parallels between them, I am working on visualizing how revolutions go through stages and are an intrinsic part of the history of civilizations. In most cases, the cycle of evolution goes from a pre-revolution phase which leads to an uprising, to the return of the old regime, and finally, to a long period when political change is impossible, a post-revolution status quo: an assessment of the number of disappeared, prisoners, political exiles, and political assassinations is extremely high.

Caroline—What is it about the visual aspect that makes protests infectious?

Lara—Many recent, historically significant social movements have started with the death of a martyr and photographs or videos of them, for example, 21-year-old Emmett Till, who was lynched in the street in Mississippi in 1955; Khalid Said, who was beaten to death by Egyptian police, and also died in the street, in Alexandria; or Neda Agha-Soltan, the 26-year-old woman, who was bluntly shot dead during the Iranian election protests, in 2009. These images represent comparable brutal acts of killing in public space, of a young, innocent citizen. They instantly become the mirror of an unjust governing system. They affect us at the chore of our being, mark the limit of what is tolerable and lead to mass protests.

Caroline—Where did the urge to document or archive the revolution come from?

Lara—I’ve been working with the Arab Image Foundation (AIF) since 1997, a cultural foundation based in Beirut, Lebanon, with a mission to research, collect and preserve Arab photography. As a visual artist and as a member of the AIF, archiving was always central to my practice. When the uprisings started in Egypt, it was a natural and instinctive response for me to start an archive. At first, it was a way to keep track of the fast changing events on the ground so I could reflect on them later. There was no time to process. But soon, it was clear that I was building an archive. My approach became more methodical. I focused my research on the new visual language that was emerging from the uprisings and by the speed at which the situation was evolving.

Caroline—Why did you decide to become an artist?

Lara—I don’t think I decided to become an artist. I think I was always an artist. As a child I used to create stories with my toys, postcards, and random found objects. Later, I had to transform this necessity into a profession. Most of my work uses traditional or popular visual references and language. As an artist working in Cairo, producing large-scale installations, when the uprisings began, I was instantly fascinated by the many creative voices of citizens, which emerged from the Tahrir, voices that never had the opportunity to speak up. Rap songs, video animations, performances, jokes—citizens were the new artists. I stepped back, observed, documented, collected, and supported as best as I could this general creative burst. I titled my archive, ‘Vox Populi, Tahrir Archives.’

Caroline—What are you working on at the moment?

Lara—At the moment, I am working on building the interactive timeline and interface of the Tahrir Archives so it can be an open source research tool. This includes making the archive searchable and easily navigable, but also building a tribute to Tahrir by creating a VR immersive experience. As part of this ongoing work, I am also designing a series of prints and a publication. The idea is to highlight important terms that are necessary to know in the process of democratization, and at the same time, to expand our way of thinking about revolutions by using scientific, artistic, literary references. Political propaganda starts in school books that teach the alphabet. My project is critical of these methods and proposes, somewhere between politics and poetics, an ABC of revolting.