“Dirty Looks,” the Barbican’s new show, remembers when grime and ruin were a language of truth and spotlights the contemporary designers still in the muck

There’s a reason we’re forever chasing the perfect white T-shirt. It never goes out of style and flatters just about everyone, until one stubborn sweat stain banishes it to the back of the drawer. It’s a classic that doesn’t last. And yet, those underarm half-moons can be strangely erotic, romantic, even political. For the designers in Dirty Looks, the Barbican’s brilliant new show, such small confessions of the body offer a way into authenticity and alternative beauty—even if fashion is often where these ideas go to die.

In the show, “dirty” extends to anything that breaks fashion’s pact with propriety. Here are clothes caked in grime, blotted with makeup, stiffened by salt, pieced from trash, frayed, and faded. The garments span decades, from the 1980s through the mid-2000s, when the likes of Vivienne Westwood and Jean Paul Gaultier built their fame on defying convention, to today, when corporatization has made such daring increasingly rare. But forgoing practicality frees certain designers from the demands that the body be polite—and thereby policed. A Di Petsa look, for instance, pairs low-rise jeans distressed at the crotch with a tank top printed with words likening bodily fluids to holy water.

What makes Dirty Looks so refreshing is that curators Karen Van Godtsenhoven and Jon Astbury don’t gloss over fashion’s mercenary and appropriative impulses. The industry might promise radicalism, but it rarely challenges the status quo. From beatnik to punk and grunge, the most cunning designers know how to co-opt those waves of rebellion while persuading their adherents that fashion is integral to their expression. That filching of subculture has produced moments both questionable and unforgettable, like John Galliano’s infamous 2000 “Hobo Chic” collection for Christian Dior. On display is one of the less provocative looks: a pair of slacks hiked above the bust and belted with a silk tie, the hems in gauzy shreds. It’s couture, mind you.

By leaning into dirt and decay, fashion gets to look real, subversive, even progressive. But it doesn’t so much embrace ugliness as broaden what counts as beautiful. Little here is more beautiful than one heartbreak of a dress from Alexander McQueen’s 1995 collection “Highland Rape,” so delicate it must be shown behind glass. In patina-green and bronze lace, it peels in paper-thin tatters from the shoulders and thighs where the fabric’s slashed. Few garments exude such raw emotion without the theatrics of the runway.

Throughout the show, the aesthetics of ruin often conceal feats of invention. A 1982 sweater vest by Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons is riddled with holes from the knitting machines malfunctioning after their screws were loosened. Equally humble in form, a dress from Hussein Chalayan’s 1993 collection “The Tangent Flows” was buried with iron filings in a garden and exhumed weeks later, when the silk had bubbled with blisters. From Issey Miyake’s 1996 collaboration with the Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang, an all-white Pleats Please ensemble bears scorch marks where gunpowder detonated. All three pieces share a modernity of spirit missing from the bulk of fashion today.

To see Dirty Looks is to understand how hard it is to build on the work of the greats. Standouts include Martin Margiela’s broken-crockery waistcoat from 1989 and plastic-bag top from 1990, and Miguel Adrover’s early-2010s hybrid garments. Twisted, inverted, cut apart, and sewn back together, they still look like the future. It makes sense for the curators to connect their ingenuity with efforts to curb the problem of overproduction. The problem is that too many of their students are tacking the “sustainability” label onto styles that rarely translate to meaningful scale. The even sadder truth is that there’s simply no need for derivatives.

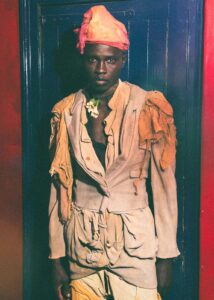

And then there’s Welsh newcomer Paolo Carzana, who seems to treat his astonishing brand more like an art project. His clothes are knotted and stitched to look as if they’ve weathered a lifetime of storms and remembered them all. Hand-dyed and available only occasionally as toiles on his website, they embody the independent and uncompromising spirit at the heart of Dirty Looks. It’s thrilling to see the thesis applied to younger or lesser-known designers, especially those from outside the big four fashion capitals, like Kampala’s Bobby Kolade and Porto’s Ivan Hunga Garcia. But the show really resonates in London, a city where this kind of spunk runs deep, even as countless names have quietly vanished from the scene. Many are here in Dirty Looks, a reminder that the industry’s obsession with the new has made not only clothes, but their creators, disposable.