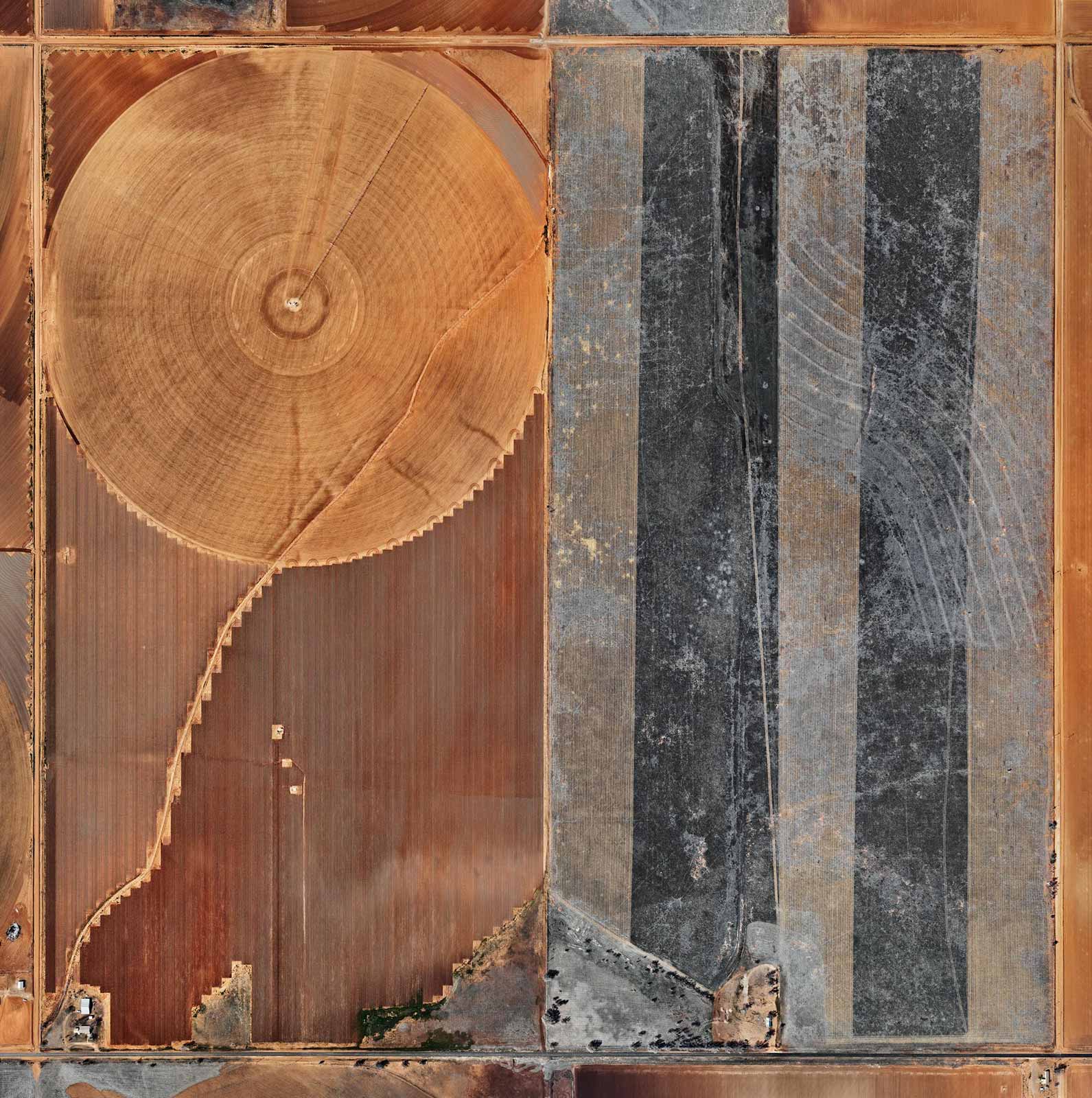

Edward Burtynsky’s 'The Great Acceleration' positions images as stark reminders that the decisions we make now will define the future of life on Earth

In the age of social media, perspective is everything. We use images to boast our access to spaces and experiences, to represent our lives with signals of relatability or exclusivity. For over 40 years, Edward Burtynsky’s photographs have used the privileges granted by perspective and access to chronicle the relentless effects human industry has on global society and the environment. Burtynsky’s visual syntax provides more clarity than ever, transcending the limits of a screen to deliver scenes and immersive murals that provoke urgency and inspire a meticulous gauge of reality.

After two decades away, Burtynsky trades his Toronto studio for a career-spanning survey in New York, The Great Acceleration, his second institutional exhibition in the city. Curated by David Campany, the show features a breadth of work that Burtynsky has championed, confronting the viewer with the seismic impact of industrial landscapes and the people who create and inhabit them. The show presents the photographer’s work not only in physical scale but in the temporal arc of Earth’s rapid transformation at the hands of humanity. The work disarms the viewer before suggesting that we are all implicated in the system. Amid the city’s density and hyperactivity, Burtynsky’s photographs serve less as alarmist activism than a stark confrontation that questions if we are ready for the price we’ll pay in environmental degradation.

In conversation with Document Journal’s Katie Rex, Burtynsky discusses the path to creating the images that defined his career, the impact of the individual, and providing access to unseen worlds.

Katie Rex: What’s the significance of showing The Great Acceleration in an area as industrial and dense as New York City?

Edward Burtynsky: New York has always been an important place for my work. In fact, in 1986, I had my first commercial gallery and first exhibition of my commercial work in New York, five years before I had a gallery in Toronto. In that period of time, I‘ve probably had over 20 exhibitions. This show is curated by David Campany, no other curator has dove into my archives as he has. He went all the way back to my student work from the late 70s and early 80s. It shows that the ideas I landed on in my mature work were already there.

I’ve always had a subset of portrait work but have never really shown, which is included. There‘s an undercurrent throughout the work looking at our impact on the planet and environment. It’s subverted. I’m not trying to point out wrongdoing, but show that this is our world as it exists today. Showing it in a way that allows for a visual gateway into these worlds, that has an impact while being visually compelling more than beautiful.

I’m exhibiting one of my biggest murals ever of an agricultural pivot irrigation circle, at 28×28 feet. It took us three days to print it. It serves as a call to action. We’re in a place in the world where the decisions we’re making now are going to be what the future is going to hold our hand to, asking, ”why didn’t you do something when you could?” I can’t help but have that feeling. I hope this show is a chance to bring the conversation front and center in New York, using photography and being able to make sure that, in the madness of what’s going on, with all of the different economic trade wars, AI, and the other existential threats around us, the only other thing that’s as much of a threat as environmental collapse is nuclear war.

Katie: You and your contemporaries have seen a city like New York, which has always been densely populated, build up to where it is today. Yet for younger generations, this is the base level, and they will observe its future growth. With this growth in mind, do you think your work impacts these age groups differently?

Edward: It’s interesting, I’ve been reading surveys on the art market. One is that a lot of the baby boomer collectors are scaling down quite often. Then, there are younger collectors coming in. It’s harder for the younger generation to afford rent, to have a decent job, and to have enough discretionary spending to buy expensive art. From this survey, what they found is that the next generation is looking for something that has more meaning to it.They either want experiences, or they want something that isn’t just novelty.

This idea is encouraging for me, because I’ve never wavered from having subtext to the works. There’s always been a constant gaze towards technology and the scale of human expansion. When I was born in 1955 there were around 2.8 billion people on earth, and we’re now 8 billion people. That’s nearly a billion per decade. In university and high school, I remember talking about the population curve that was going to happen. What interested me back in the ’80s is what was called The Great Acceleration, which is now the name of the show. I was already seeing the scale of what humans were operating at, and when I was going into factories as a young person, I got to kind of witness the scale of that at that time. And I thought, this is only going to get more expansive. It was on this hockey stick curve, all along being facilitated by technology. It gave me a North Star to pivot towards.

Katie: You mentioned that you’re also showing portraiture. As a photographer, how does the relationship with your subject change between a landscape, or broader image of people en masse, and an individual?

Edward: When I’m doing a larger scene, oftentimes the people that exist there are to set off the scale. What I aim to do in those landscapes is to show the collective impact on the landscape, the things that we do as humans using tools. Whether it’s mining trucks, diggers, or blasting systems, we’re using the tools that we’ve developed to create these worlds in which we’ve dwarfed ourselves. When you walk down the streets of New York, there are huge, concrete or stone towers towering above you. We’re dwarfed in our own cities against the backdrop of the things that we build. There’s that same kind of dwarfing in the systems to source the materials to build our cities. So to me, it’s showing that scale. You have to pull back enough to have some indicators of human scale to really understand those worlds. Usually there are individuals isolated in the center of the picture, aware of me taking the picture and aware of their own world. Who are these people that do these?

Katie: Do you get into a dialogue with them when you photograph?

Edward: I do. I ask them, “How’s it going? What do you like about your job? What do you hate about your job?” The beauty of the work that I’ve always done, whether it’s in China or Bangladesh, is that I’m in their world. It’s rare, if ever, to have visitation from a complete outsider in these areas. I’m a novelty when I visit, they’re just as curious about me. They’re all full of questions too. When I shot with a 4×5 camera, I was able to show people the little black 4×5 prints right then and there. That was always a nice way to interact with the locals and get engaged with people in a way where I’m not just standing at a distance.

Katie: A lot of journalists aim to stay on the story that they’re working on and “the why.” At what point did you see a transition into accepting your practice as activism?

Edward: I think it’s more subversive than that. I don’t really want what I consider my artwork to be too singular, like a blunt instrument to say this is bad or good. There are positives to all of the industries that develop different regions. America was able to avoid inflation, a lot of the jobs that I don’t think Americans wanted to do anyways, have left most maturing economies. Somebody should mention this to your leader as well.

Katie: What is the impact that photography can have in change, whether it’s the way people move throughout life or in shaping policy? In the environmental sphere, have you seen art and photography make an impact?

Edward: At the heart of it, humans are storytellers and we love to be told stories. We’re the transmitters and the receivers of stories and the world. The magic of photography is that we can compress the three dimensional world into images, it’s quite miraculous. By taking materials and putting them together in a particular way, allows us to send images back and forth to each other digitally, it’s not a small amount of innovation. We live in a miraculous world of potential and possibility.

Art, film, and photography are largely how we tell our stories. It’s how we communicate what’s going on in the world. How we receive information, and how we get informed about what’s going on in the world has changed quite a bit. One of the things I liked about newspapers was that you’d find surprises. You can open a broadsheet paper and see a headline where you may not necessarily be interested in the subject, but since there’s an interesting picture, you read about it. I learn something that I maybe wouldn’t have normally. I find with social media algorithms, it’s feeding you what it knows you already want. It becomes an echo chamber of your own interests. It’s measuring that and feeding it back to you. It’s a very different way of receiving information and very dangerous too, because it’s very addictive.

We have to keep this conversation going and push back against the things that are undoing all of this. It ain’t over till it’s over. We don’t have a lot of time left, things are moving ahead pretty rapidly and we’re moving the deck chairs around on the Titanic. With activism you have to ask, ”how do you change people’s hearts and minds?“ You have to show the facts in many ways. The way I built out my work, it’s not open to interpretation in enough ways to deny the subject matter. If someone is a climate change skeptic and believes this is what the planet does normally without human intervention, they need the facts presented to them in a way that‘s didactic. If information is introduced in a way that isn’t threatening, then there’s a chance to expand. You can get those people on the margins that could be convinced, but they just haven’t seen anything or felt anything compelling enough to say. Can you bring them under the tent? I think that’s the most interesting place.

The Great Acceleration, is on view through September 28th at the International Center of Photography