The inaugural AIR Festival blends art, science, and performance in Aspen, reviving its history as a crucible for cultural and technological exchange

On my first morning in Aspen after a many-legged journey from Paris, Stella Bottai, one of Aspen Art Museum’s curators at large, asked, “When the light comes in and the blue disappears…what happens collectively when we have these moments of awakening?” She was reflecting on dreamstates and the transition into waking life, proposing the question in Aspen Chapel, just after dawn at the first event of AIR: Life As No One Knows It, the museum’s inaugural AIR Festival.

Attendees had all just experienced On Blue (2022), a collaborative video performance by Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul and composer Rafiq Bhatia. The hypnotic film sequences of a woman sleeping were intercut with shifting backdrops of a Thai folk theater set in a forest as the day breaks and scored to an ambient composition performed by the Aspen Music Festival and School. The experience set the tone for a week-long series of performances, exhibitions, and talks, which unfolded at the historic Aspen Institute and other venues across the mountain town and brought together a wide range of participants.

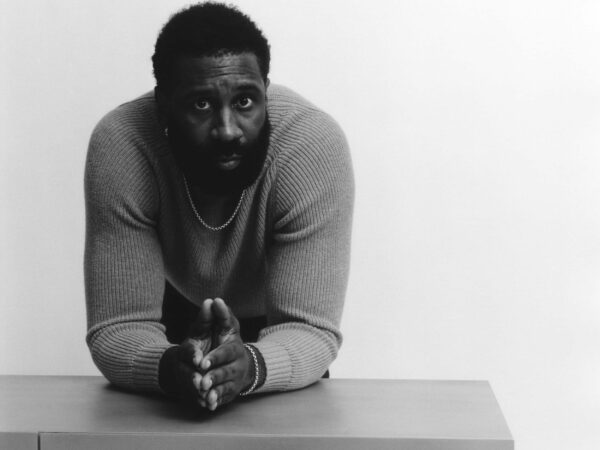

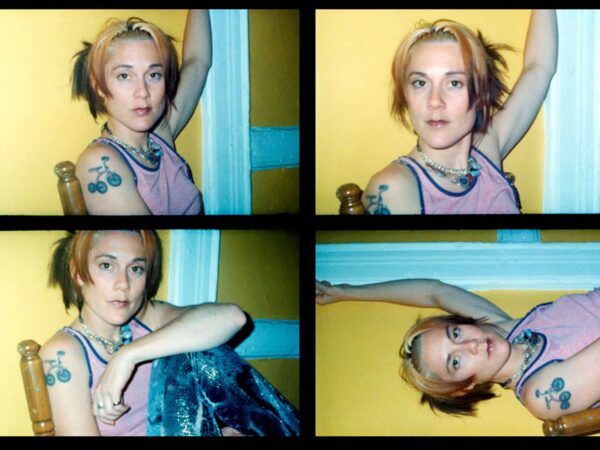

AIR, a vision of the Aspen Art Museum’s Artistic Director & CEO Nicola Lees, was formatted somewhere between a conference and an adult summer camp, allowing participants to explore ideas and reconnect with each other over several days. At a keynote speech, artist and architect Maya Lin asked if we as a society “can face death honestly?” Elsewhere, art world luminaries Thelma Golden, Director of The Studio Museum in Harlem, and artist Glenn Ligon discussed friendship. At a rooftop concert, genre-defying singer Caroline Polachek’s voice seemed charged by the storm which roared through Aspen some minutes before. Poet and technology researcher Zoë Hitzig cited writer William Blake’s contempt for scientist Isaac Newton in the eighteenth century, believing his research to be an existential threat to culture, as a precedent for our current cultural reckoning with new technology.

Inspired by the legacy of the Aspen International Design Conference (1949-2006), which gathered radical thinkers such as John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Susan Sontag, and Steve Jobs to “envision the cultural and technological future that we now inhabit,” AIR’s organizers asked “what does it mean to be human at a time when life itself must be redefined?” To address this, AIR continued an Aspen tradition of meaningfully engaging with scientists, technologists, and architects, alongside artists. Following the inaugural performance, psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster and artist P. Staff meditated on the interconnections between dreams, disorder, death, and ecological crisis. When discussing a toxic or polluted yellow, used in their installations, Staff explained that they “don’t extol the virtues of this, but maybe pollution is delirious joy.” To which Jamieson shared that “Freud has a quote that we didn’t produce fire because of technology, but to piss on.”

This interplay between poetic impulse, formalism, technology, and ecology was a resonant topic throughout the program. In a refreshingly tense moment in the ensuing talk between Sophia Al-Maria and physicist and astrobiologist Sara Imari Walker, the gap that can open when art references science became palpable. Walker, whose book Life as No One Knows It inspired the festival’s title, pushed back on Al-Maria’s discussion of collective experience to argue that from a scientific perspective, “an experience is not shareable. You can talk about it, but you can’t share it. You can communicate with language. But language is discrete. It’s a poor form of communication…” In artmaking, this becomes a useful limitation for the presentation and translation of ideas.

At architect Francis Kéré’s keynote lecture, the power of creativity was reinforced when he exclaimed, “Without artists, without fiction, what would be our world?” The group was led away from the museum’s rooftop and to the Aspen Center for Environmental Studies (ACES), an environmental science education organization at the edge of the idyllic Hallam Lake. As the rain lifted, the crowd was beckoned deeper into the reserve by the calls of a seeming ritual—a site-responsive opera by artist Jota Mombaça. Departing from Mombaça’s 2023 short story Stuck in Movement (in the Tide), the performance unfolded in three parts, with a magical moment where a musician led the group to the foot of the lake. There, one of the artist’s collaborators emerged from the treeline, seemingly floating on water or, as the artist’s text suggests, transitioning from the water.

Matthew Barney’s TACTICAL parallax was the most ambitious commission of the festival. All attendees were ushered into shuttles at the museum and caravaned through the Roaring Fork Valley to the McCabe Ranch, a private, family ranch with vast mountain vistas. We were led into a riding arena repurposed from the former drill hall of the 10th Mountain Division infantry. The performance was a series of choreographic acts that combined sequences from his previous works for the first time, such as the hunt iconography from his film Redoubt (2018) and the pageantry of sport for violent entertainment in Secondary (2023), an installation inspired by a historic NFL hit that left one player paralyzed for life.

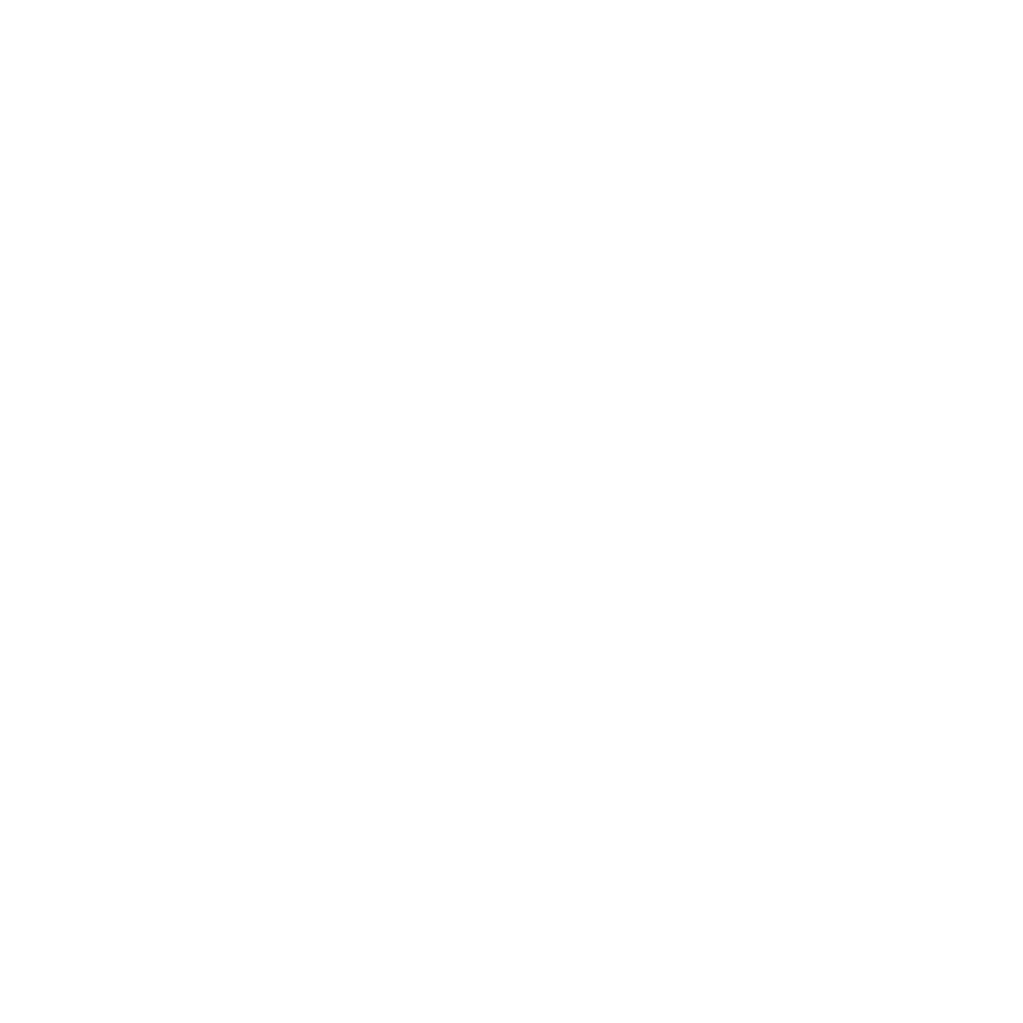

The piece began with Barney, in full Western gear (think cowboy boots, hat, jeans, flannel), drawing lines in chalk across the arena and setting up the lines of play, of battle, of presentation. Over the next hour, marching bands, referees, football players, hunters, horses, and dogs with their trainers teed off—in some sequences facing an opponent and in others performing for the crowd. In one of the more tense moments of the piece, artist and choreographer Okwui Okpokwasili took the center of the arena, wildly dancing in a fabulous Prada-designed black fringed dress, and delivered a monologue on the notion of repetition and endurance, ending her sequence by straddling and dismantling the gun of the character Diana—a reference to the Roman goddess of the hunt, central to Barney’s film Redoubt.

Barney has a keen ability to dissect symbols and mythologies, distorting the line between spectacle and reality, and an eye for the particular violence that pervades the American landscape. Within the context of the Rocky Mountains, the piece pushed further resonance about real and imagined symbols. Some time after the performance, Jota Mombaça and I spoke outside of Grateful Deli, a quirky Grateful Dead-themed sandwich shop. We reflected on which references in the piece might be “really” American and which are fictions. As a New Yorker, the vision of an American Midwest in the US—of cowboys, guns, ranches, and horses—is just as much a cultural imagination for me as for the Brazilian artist I was speaking with, who might draw from a film or the news about the United States a vision of a place somewhere between reality and cultural construction.

Aspen offers a particular context for considering these realities. It has gone through many transitions—from mining town to hippie refuge to academic nexus to haven for the ultra-rich. It exists with the legacy of all of these iterations, with the museum at its cultural center. A non-collecting institution founded in 1979, the Aspen Art Museum has operated as a more professionalized institution in the last decades. Through AIR, the team is tapping into a more experimental ethos, referencing historic Aspen initiatives around research and public discourse, though adding a museum’s perspective by centering live performance and visual art. In doing so, they’re returning to their artist-driven founding roots, allowing artists to lead and push the conversation forward.