Once nurtured by New York’s downtown scene, the choreographer now confronts an arts ecosystem in flux, and exits on his own terms

“Eve just had knee surgery,” veteran dance publicist Janet Stapleton tells choreographer Stephen Petronio as I walk into an East Village dance studio.“Make sure you use your glutes when you walk up stairs—you don’t want to rely on your quads,” Petronio warns me. “A physical therapist at New York City Ballet told me that.” Stephen’s conviviality evokes the New York City downtown dance scene of the ’70s—a contrast to the strict ballet instructors of my youth.

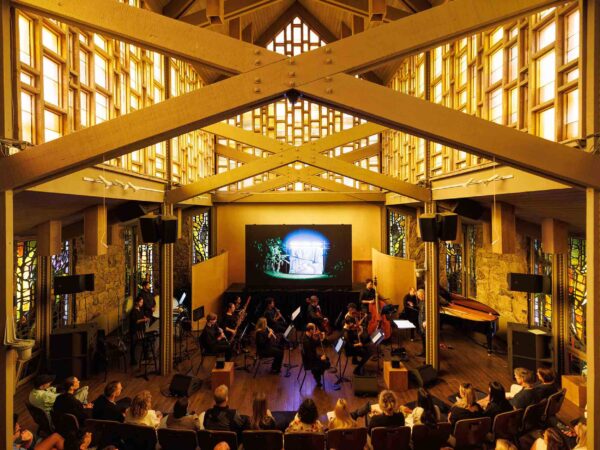

After forty years as Artistic Director of his eponymous company, the Stephen Petronio Dance Company, Petronio has decided to close shop—a financial decision brought on by shifting interests in both private and public sources of funding. Earlier this month, I attended a rehearsal at the New York Center for Creativity and Dance to watch his 1990 masterwork MiddleSexGorge, part of the company’s program for their final-ever performance this July at the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in Beckett, Massachusetts.

Watching the rehearsal, I detect the highly technical and aligned movements of Merce Cunningham, the father of postmodern dance. Petronio has taken these exercises and thwarted them, adding undulation, speed, and syncopation in the hips and torso. I imagine this is how the first generation of Cunningham dancers moved at The Palladium on weekends in the ’70s—letting loose after hours of rigorous training in the studio. This is not far off from Petronio’s origins. He was the first male dancer in Trisha Brown’s company—a younger contemporary of Cunningham’s and a pivotal postmodern choreographer famous for her use of pedestrian movement and popular music like the Grateful Dead’s Uncle John’s Band.

Born into a working-class Italian-American family in New Jersey, Petronio became the first in his lineage to attend college, securing a scholarship to Hampshire College. “Because I was the first to go to college, I was going to be a doctor,” he tells me in his office, filled with boxes of the company’s archives and costumes. At school, his plans changed when a girl told him he danced well at parties and suggested he sign up for dance classes. In one of those classes, Improvisation, he had what he describes as a “thunderbolt moment.” “[I] looked down and said what the fuck is this… I realized I had a body!” When Steve Paxton, the founder of contact improvisation and later one of Petronio’s mentors, came to teach a masterclass, Petronio’s cursory interest became a singular focus. With his friends, inspired by Judson Dance Theater—the dance collective most closely associated with bolstering downtown postmodern dance in New York—he began choreographing in a group called The Wood and Air Collective. He graduated and moved to New York. With only four years of formal dance training, he auditioned for companies until he ultimately landed in Trisha Brown’s company.

Even as a company dancer, Petronio kept choreographing. For $100 a month, he rented the basement space at 541 Broadway, where Brown owned a loft on top of Lucinda Childs, another pioneering choreographer in postmodern dance. There, he put on performances attended by Brown and other artists like Robert Rauschenberg. Petronio launched his company in 1985, just as the AIDS crisis began devastating the city: “Just when I was beginning to feel the freedom of being a queer man in New York.” He joined ACT UP, attending protests and lie-ins across the city. It was at a City Hall protest, when Petronio was grabbed and carried off by cops, that he started to connect his training in contact improvisation with his nascent political activity: “giving up control to fight for what I believed in.” It is this connection between partnering and ceasing control that inspired MiddleSexGorge. The piece recreates Petronio’s experience of being thrown into a paddy wagon by policemen.

“My dances look like my brain, my brain looks like my dances.”

“I saw everyone,” Petronio boasted, recalling the major choreographers of the postmodern period: Merce Cunningham, Yvonne Rainer, Lucinda Childs. “I didn’t like Merce’s movement in the beginning because it was taut and stiff, but I kept going back to it because he’s a genius and I was a good student.” Petronio was learning to choreograph from masters. In 2014, 29 years into his own company, after Cunningham died and Brown became sick, Petronio established Bloodlines, a project within his company to celebrate the history of postmodern dance. As part of Bloodlines, the company will perform Yvonne Rainer’s Chair Pillow (1969) at their final performance at Jacob’s Pillow.

Working with these masters gave Petronio the opportunity to define and hone his own choreographic approach. “My dances look like my brain, my brain looks like my dances,” he explains. While drawn to the exploration of movement, he’s equally concerned with the appearance of a piece. “I’m interested in chaos and force, polyrhythmic, multidirectional invention, but… I’m also deeply superficial,” he explains. There’s also an undeniable element of sexuality. Petronio challenged notions of “artiness” and put sex on stage because “sex was important to me,” he insists; but this is also an extension of Petronio’s activism. He challenged taboos by centering sexuality on his stage in the immediate aftermath of the AIDS crisis, a time when sex was dangerous and stigmatized. “Why can’t that be part of what’s on stage? Why does it have to be taboo?” he asks. At the same time, he was seeing a lot of Balanchine—the legendary founding choreographer of the New York City Ballet. “Balanchine put his foot down on the gas, which was a good vice to follow, so I put it down harder… you have to be sort of insane to dance for me.”

The decision to close the company is financial. “It’s impossible to run a dance company in this country,” Petronio asserts. Under the country’s current administration, arts organizations of all types and sizes have been affected by recent cuts at the National Endowment for the Arts. This past May, the NEA pulled a $40,000 grant from Petronio’s former troupe, the Trisha Brown Company. After funding his company partially through the private sale of art pieces gifted to the company by Anish Kapoor, Robert Longo, Cindy Sherman, and Robert Rauschenberg, Petronio purchased a property in the Catskills, used as an arts residency for seven years. Then the pandemic hit. While he kept things afloat during COVID, even managing to raise more money, institutional priorities shifted post-pandemic, with cultural institutions altering their funding priorities to efforts of diversity—a cause Petronio very much believes in. But as a 69-year-old white man, he read the writing on the wall. Petronio, along with his board, decided to sell the residency and use the proceeds to fund one last round of performances.

“What about the dancers?” I ask, instantly worrying I sound callous. “Ahh!” Petronio yowls before succumbing to tears. “I’ve taken care of them for a long time.” I resist the urge to cry and put my hand on his shoulder, but Petronio suddenly perks up and declares that the dancers will continue his legacy.

“When Martha Graham died, we learned a lesson,” he says. Petronio retains ownership of his dances, which will be licensed for future use. The proceeds from the sale of the residency will go toward a foundation to support the work of future artists, in line with a project he titled Bloodlines (Future)—an extension of the Bloodlines project focused on supporting the next generation of young dancers, particularly dancers of color. “My postmodern world is very white,” he laments. He will have a year to decide the recipients.

This closing represents more than the loss of one company and its works. Petronio embodies a bygone method of art-making. In his day, New York was not only friendlier to artists—he lived on St. Mark’s Place for $250 a month and made a living from teaching a class advertised in The Village Voice—but his generation saw art-making as a moral act. Petronio’s origins in dance sprung entirely out of curiosity. As he describes his concurrent training in technique and choreography—“I was introduced to dance with the creative process”—I compare his trajectory to the paths of contemporary choreographers, particularly in ballet companies: only after years of training do some take a stab at dance-making. In MiddleSexGorge, the piece’s dramaturgy—its internal structure—works completely. Every exit and entrance is imbued with a well-earned knowingness. One realizes that so much of Petronio’s talent stems from the multidimensional background that launched him.

I ask him what’s next. “I had a psychic reading the other day. The psychic said she saw me riding into the spotlight but on a bicycle that was too small for me. I came home and realized I needed to make a change.” He needs to find a bigger bicycle, we say, almost in unison.

The Stephen Petronio Company’s final performances will run from July 23 to July 27 at Jacob’s Pillow.