Legendary editor Amy Scholder revisits Wojnarowicz's searing work on queer consciousness and erotic memory, now reissued by Nightboat

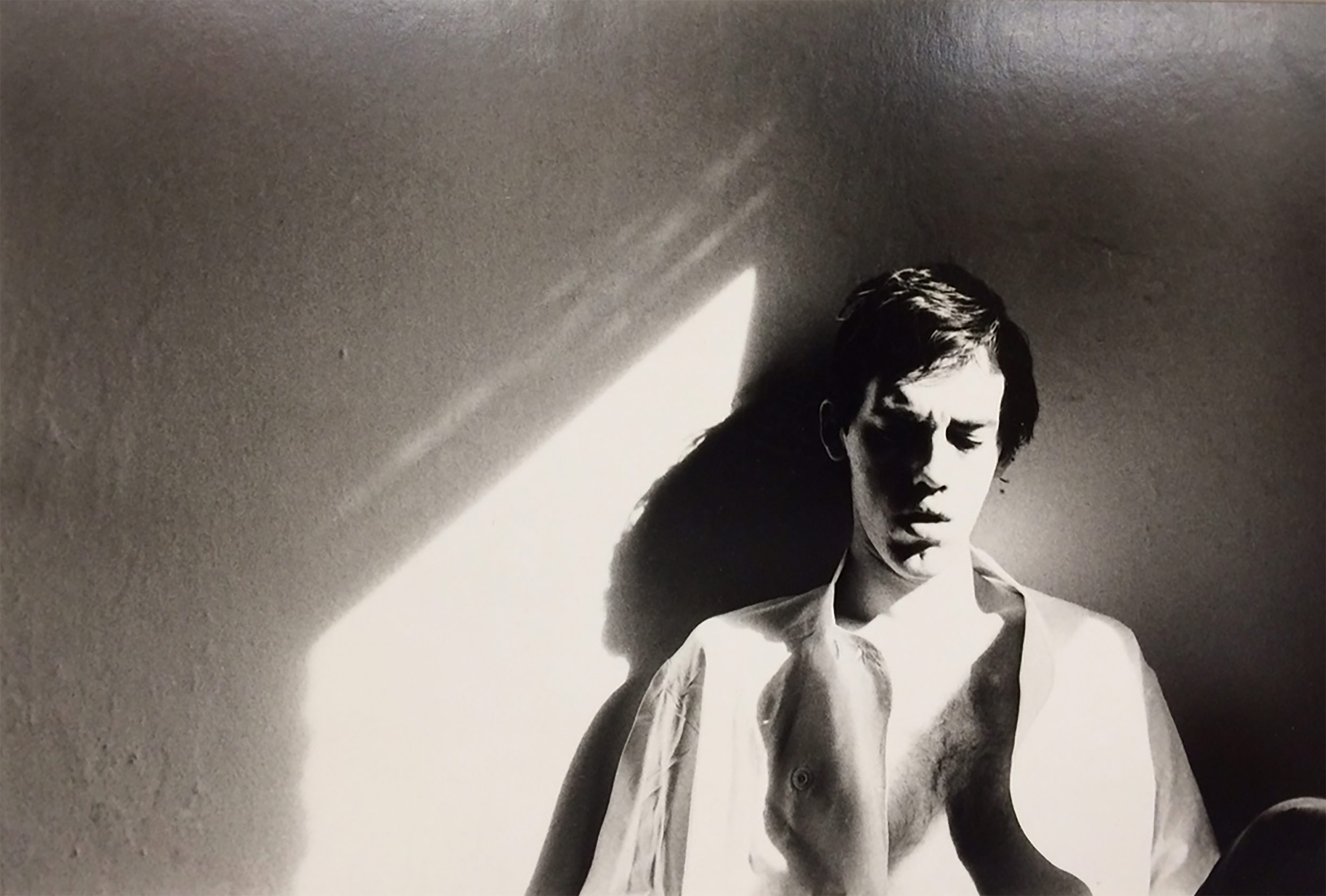

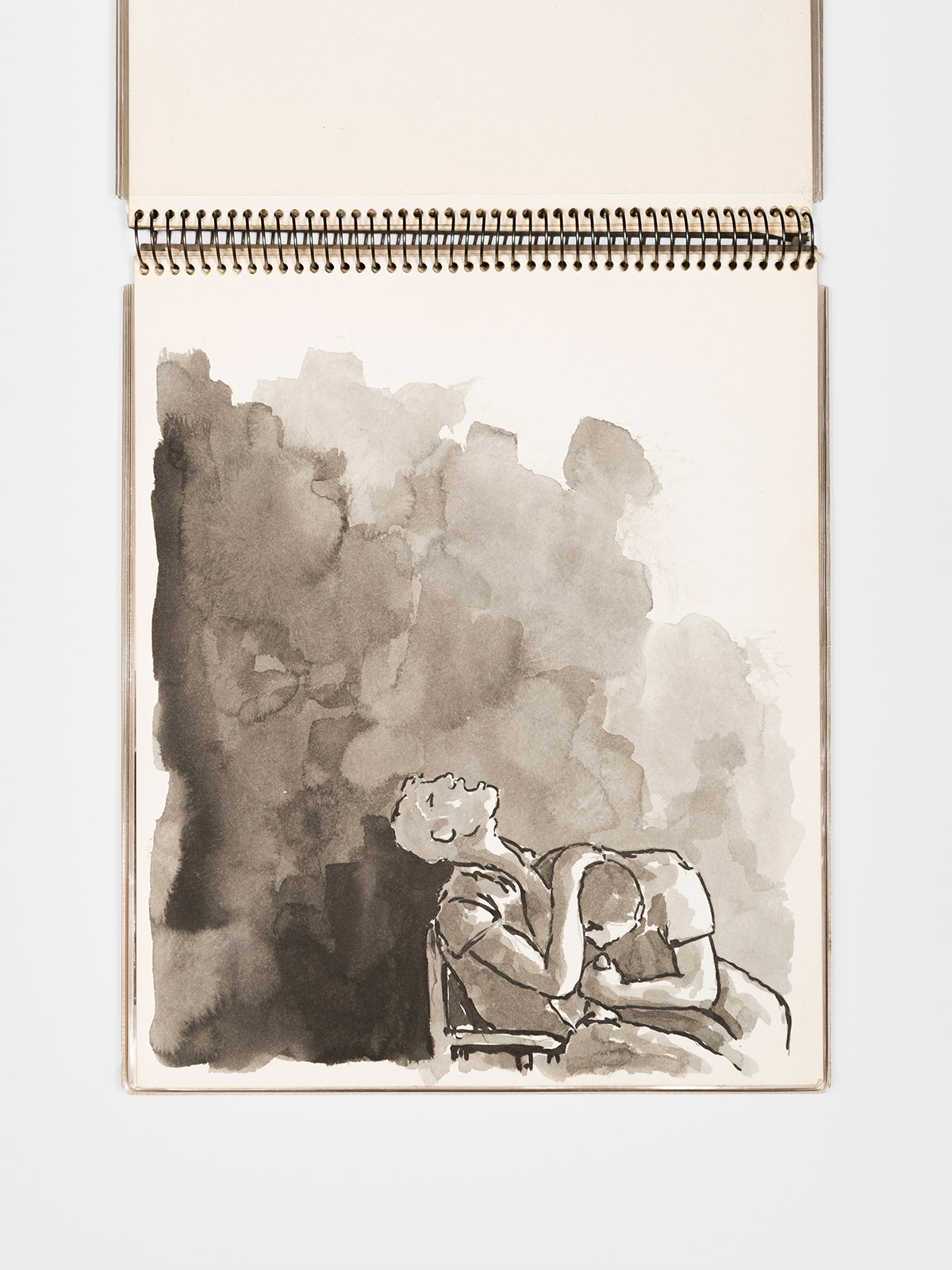

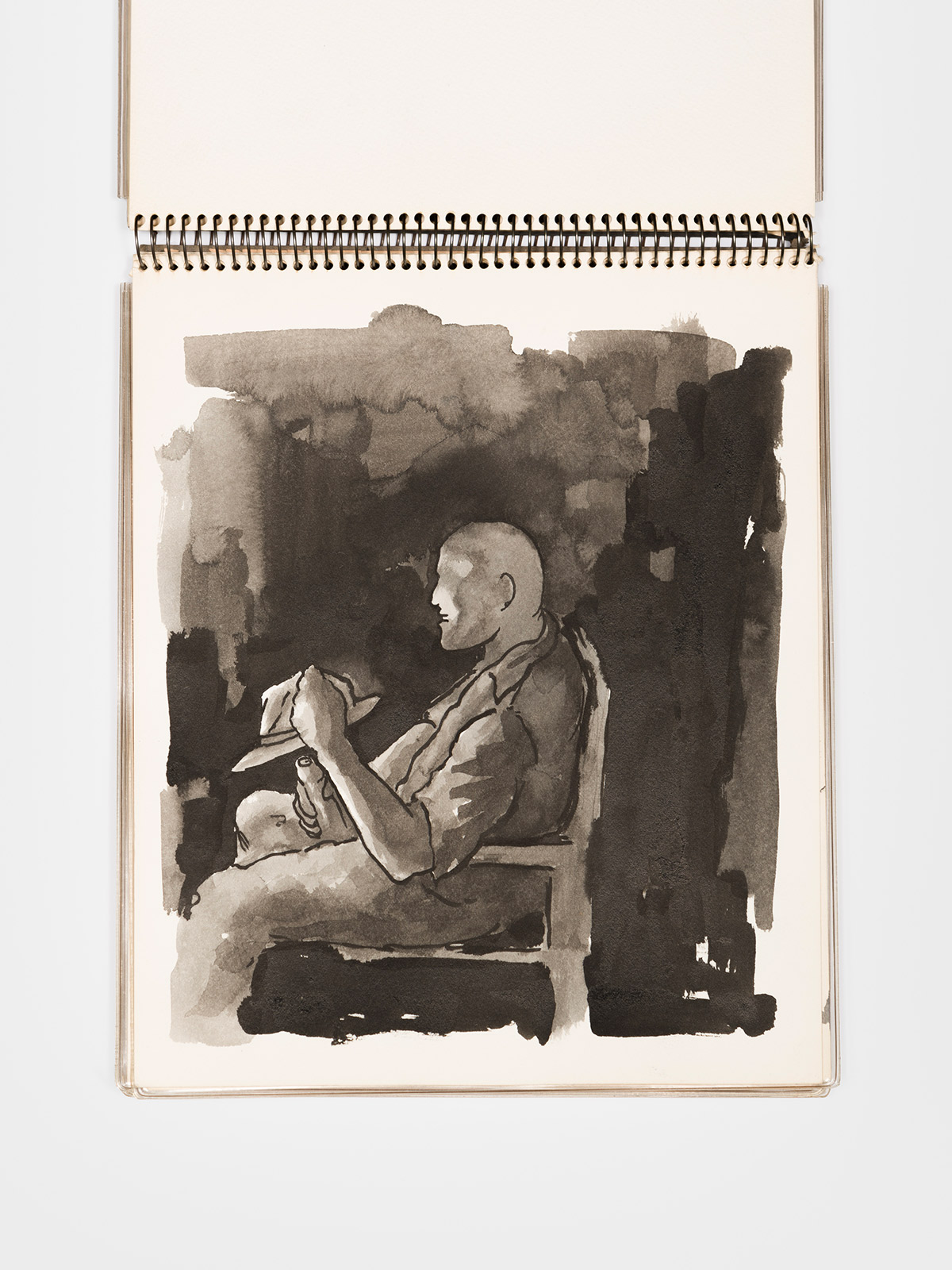

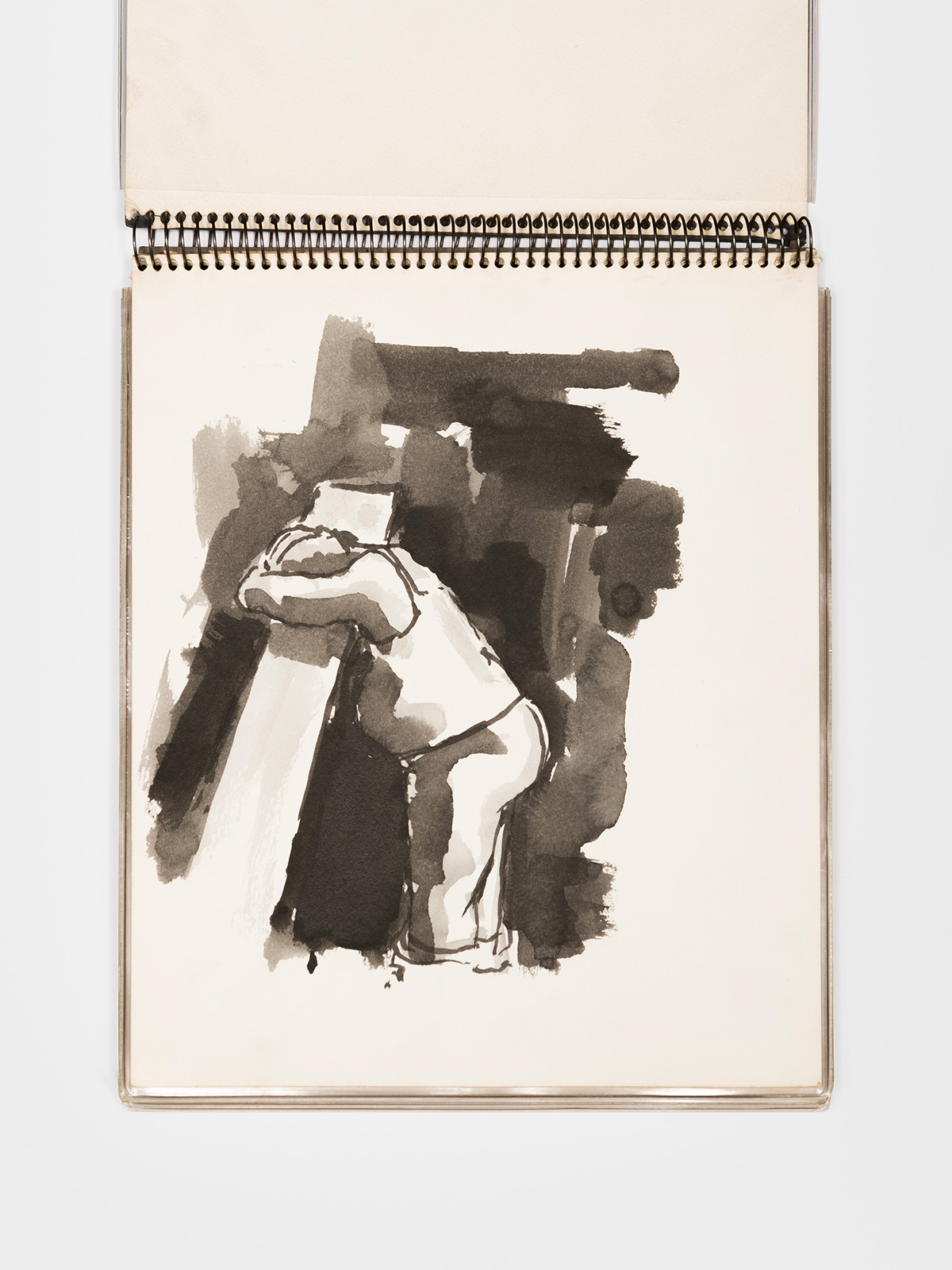

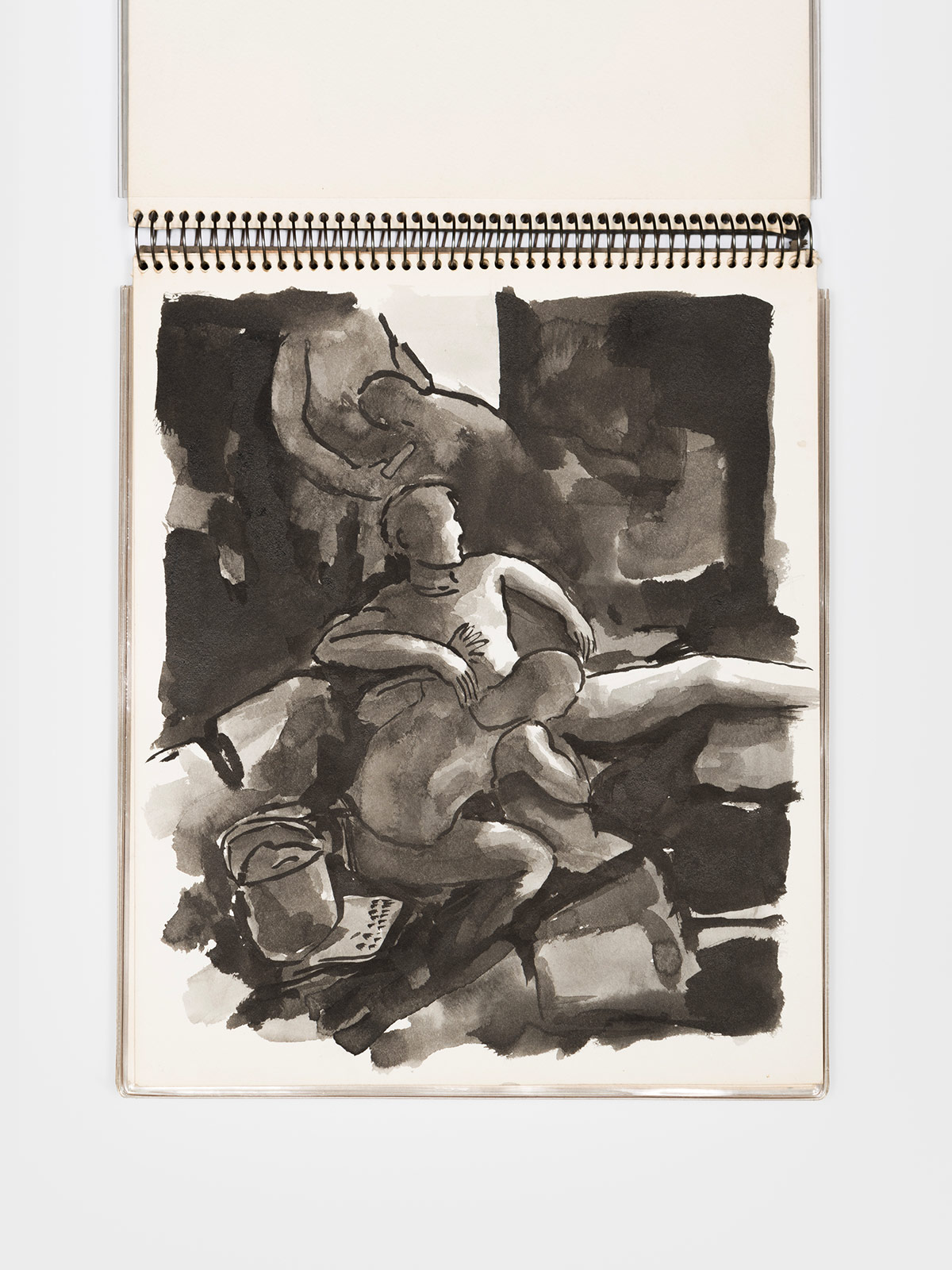

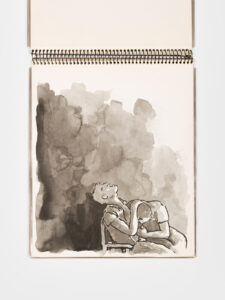

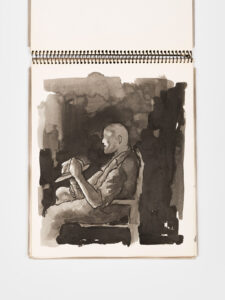

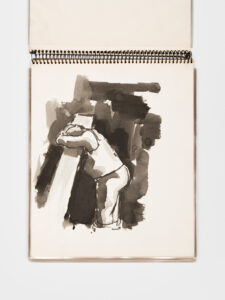

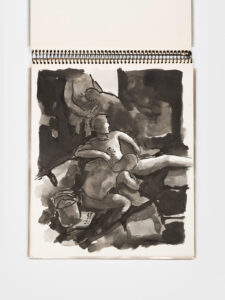

To read the stories in David Wojnarowicz’s Memories That Smell Like Gasoline is to rush through the particularity of consciousness into the totality of being. His prose reshapes time through eddies and loops and, in turn, reshapes what narrative prose can be. The individual and the other, the singular and the societal jostle, blur, explode. Corporeal presence contains both fantasy and truth. In “Doing Time in a Disposable Body,” Wojnarowicz writes, “I associate with certain gestures or body language or scars or other physical characteristics an entire flood of memories and fictions and mythologies.” In the book’s title story, the narrator sees a familiar face, which, like a haunted madeleine, unspools a violent experience from perhaps more than two decades past. The repetition of the word “gray” throughout the stories acts like the light and shadow of paintings, where memory’s murky light evacuates color. There are literal grayscale images in this book too: watercolors of hookups in porn theaters, and drawings captioned with stories from Wojnarowicz’s days turning tricks as a kid on the street.

The artist died of AIDS-related complications at age 37 in 1992. He continues to be exhibited widely (the Whitney had a retrospective in 2018; the Leslie-Lohman Museum hosted a program inspired by his early photographs this spring, which the institution will exhibit later this year). And his work continues to stir up reactionary, conservative controversy. While some of his books, like his seminal Close to the Knives, remain in print, Memories has been unfairly out of print for years. However, readers now have access to these stories and artworks: Nightboat has put out a beautifully designed new edition, featuring an introduction by Wojnarowicz’s editor, Amy Scholder, and a foreword by poet Ocean Vuong.

Scholder’s 40-year-long editorial career is the stuff of legend—beginning at City Lights in 1985, she would go on to work at Verso, Seven Stories, and The Feminist Press. But she published Wojnarowicz with High Risk Books, an imprint of Serpent’s Tail she co-founded with Ira Silverberg in 1993. The press put out radical books that transgressed stultifying social and artistic norms by the likes of Dennis Cooper, Akilah Oliver, Lynne Tillman, Darius James, and Kate Bornstein. Begun during the heights of the HIV epidemic, High Risk also published those the virus and society conspired to silence.

Now based in Los Angeles, Scholder has expanded her creative vision to produce queer-centric documentaries like Disclosure (2020), My Name is Andrea (2022), and, most recently, Heightened Scrutiny (2025), a film following ACLU attorney Chase Strangio as he argues United States v. Skrmetti, the case on gender-affirming healthcare for minors which the Supreme Court decided last month.

Document called Scholder to discuss her work with Wojnarowicz and what has and hasn’t changed in the landscape of radical art and queer life.

Drew Zeiba: Beginning in May, the National Endowment for the Arts has cut funding to many small presses, including Nightboat. Of course, David faced censorship by the National Portrait Gallery in 2010 and over NEA funding for an essay to be published by Artists Space during his lifetime, in the late 1980s. We’re also seeing renewed attacks on healthcare for queer and HIV+ people. This moment feels full circle in the most perverse way. Obviously, the republishing was in the works before this. But I’m wondering why you were revisiting this book when you were, and now how you’re thinking about the context it will enter.

Amy Scholder: This was the first book that David and I worked on. David was still alive at the time, and we had met through correspondence when I was a young editor at City Lights and we talked about various projects we were hoping to do together, and this was the one that we had the time to make. It’s especially significant to me that we were able to make this in his lifetime and he saw it shortly before he died.

I’ve been really interested in the work that the Wojnarowicz Foundation has been doing to sustain David’s legacy since he died, especially now. The first executor of the estate was Tom Rauffenbart, David’s lover of many years, and when Tom died, Anita Vitale, Tom and David’s friend, took over the foundation. So Anita and I have been in conversation about the work that can be done to help raise the legacy of all of David’s work when we realized that Memories had been long out of print. When we were talking about what would be really meaningful, it was to have this book gain a new audience.

Nightboat was our first choice, because they publish such beautiful books that go across genres and could accommodate an interesting design, and the fact that this has visual art in it, as well as text. So I was thrilled that Stephen [Motika] wanted to reprint the book and Anita and I really were committed to really finding new audiences for this book and one way to do that was to think who might write a foreword that would attract that new audience. Ocean Vuong was our first choice. I love the work. I think he’s an incredible poet, and his sensitivity around being queer in America seems particularly relevant to this book and to David’s work. I happened to be looking at things he’d written and found that somewhere online he had been asked some of the most important books to him and one of them was Close to the Knives by David. So it seemed especially apt to ask Ocean to write the foreword, which he graciously did and which I think is so beautiful and situates the book now.

We were in the middle of the AIDS epidemic with no end in sight in 1992 when the book came out. David was very sick and died a few weeks after he saw the book. In terms of the timing of it coming out now, I think there’s yet again this sense of urgency and crisis in the queer community. In a heartbreaking way, we are again [in crisis]—under different circumstances, a different crisis, but in a way, one even more sinister, perhaps because it’s so disconnected from anything that’s happening. There’s no epidemic that’s wiping out a significant portion of the queer population—and instead it’s a brutal, vicious mentality that seems to be taking over the country. One way in which we see it manifest is in funding for the arts. Here we are again in another calamitous moment for queer and marginalized communities and it happens to be when we’re bringing out this book in a new edition.

Drew: What has been your personal experience spending time with Memories again in this way?

Amy: It’s interesting to read the stories that go with the watercolors. David had this notebook that he shared with me when I was visiting him one day in his loft on East 12th Street and Second Avenue that he had inherited from Peter Hujar. He showed me this beautiful spiral-bound notebook of watercolor paper. He had basically been going to these porno theaters and watching men around him having sex, and then going home, and from memory, making these drawings of what he saw, what he remembered, and then writing about these experiences.

What always strikes me about David’s depictions of sex with strangers—when it isn’t about some abuse that happened to him, but when it’s about basically what we now call hooking up in public places with anonymous partners—is he writes about it with such tenderness and passion and eroticism and real depth of feeling about the man he’s with. It’s so different from the kind of hookups that are described that often happen through online means. I’ve just always loved that about David’s work and found in rereading that still feels so fresh to me and meaningful to think about how queer people in particular might find real connection in the dark through their sexuality, and not have it be less than meaningful or significant just because it’s outside the parameters of normal dating and relations. He defied that gay-male culture around sex being just kind of meaningless and marathon and functional. There’s something so particularly queer about it, and I love how that has endured for me.

His depictions in the second part, in the ‘Spiral’ section, of what it was like to be in the midst of the AIDS epidemic and lose so many loved ones, and then, in his case, to be so ill and be facing down his mortality and do so in real time with his writing and drawings, to me, still feels like, ‘How did he do that?’—be so expressive and productive in the face of this completely existential moment for him?

Drew: There’s such an amazing way the texts and the watercolors and drawings cycle in and out of time, both within themselves and between each other. I was really struck by the images in the title story, which is largely him recounting being sexually assaulted at 15. There are those porno theater watercolors you were describing, which are so erotic and affectionate. But in the ‘Spiral’ section we have these more narrative images that discuss being a child sex worker. These threads coexist so dynamically.

In his intro, Vuong writes, ‘Heteronormative readings of precarious Queer experiences, especially of casual encounters among gay men, have often been reduced to “trauma” or critically pigeon-holed as “trauma porn.” Wojnarowicz reminds us, however, that trauma, clinically, is what’s felt by an individual—not the action itself…. This is why Wojnarowicz’s ambivalence, his refusal to shame and judge Queer experiences, while absolutely condemning the judgment of the state, feels so powerful to me today.’ It was amazing to see and read the many different dynamics of feelings—often contradictory feelings—that are held together in this book.

Amy: I think back then there was also this point in culture where there was little space for the multiplicity and the complexity of experience around sexuality and sexual trauma. Back then, there was also this added criticism around depicting unsafe sex, and there were all of the parameters writers were supposed to have around their imagination, which, of course, was foiled over and over again and rejected over and over again by writers like David. But yes, part of what’s so beautiful about his writing and his storytelling is that he’s able to not just become that storyteller of the sexual trauma or the abuse, but is equally able to conjure all of the ways in which he has felt sexual liberation and personal liberation through his encounters of queer sex. It’s hard to do that, and it’s hard to be known for both. I think that because all of it was equally defining for him, he was really unwilling to give up part of that work.

Drew: You co-founded High Risk books as an imprint of Serpent’s Tail with Ira Silverberg back in 1993, and I’m looking at one of my bookshelves right now and I see the original High Risk Jack the Modernist and the NYRB reprint of Margery Kempe, both by Robert Glück. There’s been so much recent attention revisiting High Risk authors like Hervé Guibert and Guillaume Dustan. I wonder how you look back at that moment of transgressive literature and the clear interest in it now.

Amy: A number of Gary Indiana books are being reprinted. And Semiotext(e) has been doing some wonderful recuperation of Cookie Mueller, and they put Ask Dr Mueller into their Cookie collection [Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black], and that was really gratifying. I’ve been happy to see how those books live on, even though, like many, many small presses, Serpent’s Tail was not able to keep all of those books in print. Some of them have been revived in new editions. I’m really happy about it. Ira and I had this mandate to publish books that were from writers who were not finding homes in mainstream publishers and to tell the stories of people who weren’t in the mainstream in beautiful, interesting literary ways. So that mandate was broad enough, I think, to corral a lot of very different voices together into one imprint. June Jordan’s Love Poems and Sapphire’s American Dreams of poems and short stories felt right to live in the same imprint with Cookie’s downtown writing. I’m proud of that work that we did, and I don’t think I could even make a generalization about why and how the work is resurfacing now, except that I think it’s because they’re really great books.