Jack Shainman’s upstate school-turned-gallery hosts 29 artists grappling with the current weight of the world

Why bother making art when the world is on fire? This question has been asked throughout history during times of global tension. Artist and punk figure Patti Smith pondered it over in a 1970s diary entry in her memoir, Just Kids, when she wrote, “In my low periods, I wondered what was the point of creating art. For whom? Are we animating God? Are we talking to ourselves?” In the same passage, she bemoaned the catch-22s of producing work for the hegemonic walls of large institutions, and the “overwhelming bureaucracy” barring her alignment with political movements.

That passage was written against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, simmering racial tensions in the United States, and the socioeconomic battleground that was then New York City. Today the world is in an eerily similar moment, with increasing political and social inequity brought to the surface, a refugee crisis, war and genocide abroad, and a rapidly warming planet. A sense of disillusionment with the powers that be pervades amongst the masses. Artists may find themselves asking the same question Smith was asking in the ’70s: what’s the point?

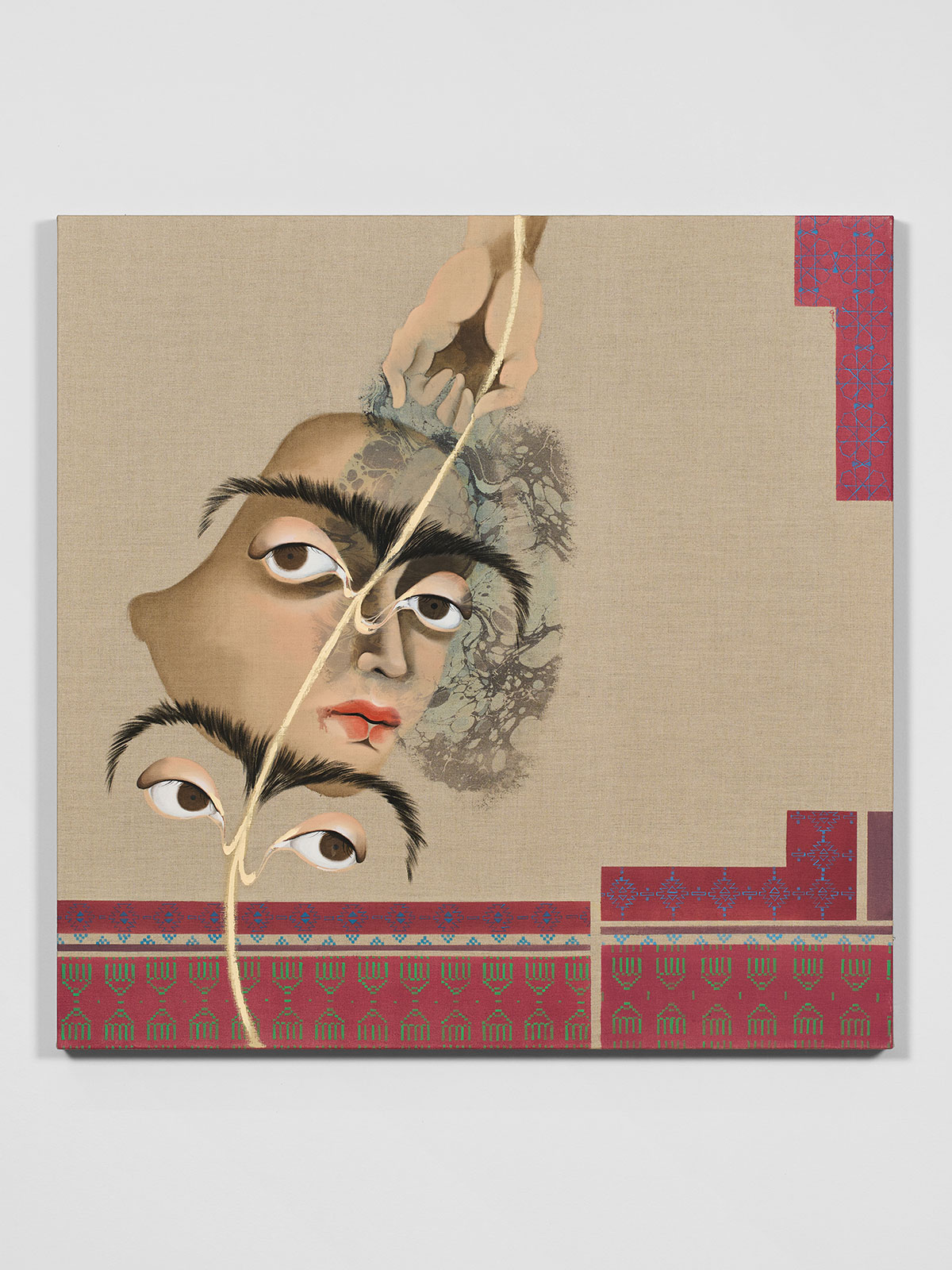

General Conditions, on view through November 29th at The School, Jack Shainman’s upstate gallery, is an exhibition of 29 artists across 130 works responding to this daunting question. Curated by Shainman himself, General Conditions aptly refers to both the current climate and turbulent times past—from the watchful eyes in Iraqi-born Swedish-American artist Hayv Kahraman’s multimedia works on paper, dealing with themes of migration and displacement, to the oppositional gaze of Gordon Parks’s Civil Rights-era photographs, highlighting Black communities in the segregated South.

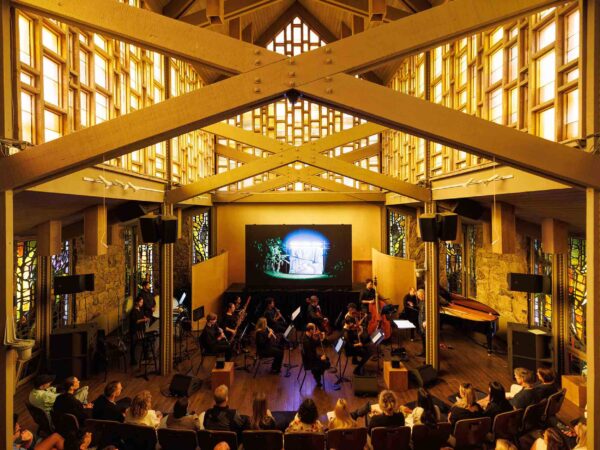

Amid the quiet valleys of Kinderhook, New York, in a 30,000-square-foot former high school building, The School serves as both an extension of and an alternative to Shainman’s two NYC locations. Asked how the curatorial process differs across the three spaces in an interview for Document, Shainman notes that even the lighting is different in the airy upstate space. “Sometimes there can be something that was so dark in the city that can be so unbelievable [at The School].” This abundance of light, particularly in the context of General Conditions, brings levity to such dizzying subject matter—things come into focus just a bit more clearly.

Entering the schoolhouse’s double doors, visitors immediately confront Jaclyn Wright’s installation, Desert Simulation (2025). An array of 10 shooting targets covered in bullet holes stand staggered against a photograph of an arid, blue-sky backdrop—an ambiguous location, presumably the American West. The installation floor is littered with colorful bullets and tattered fire extinguishers. In Wright’s work, largely concerned with issues of land use, late-stage capitalism and settler colonialism, the punctum, or emotionally-charged piercing detail of an image, is rendered literally. And in this wasteland tableau, we are struck more than once.

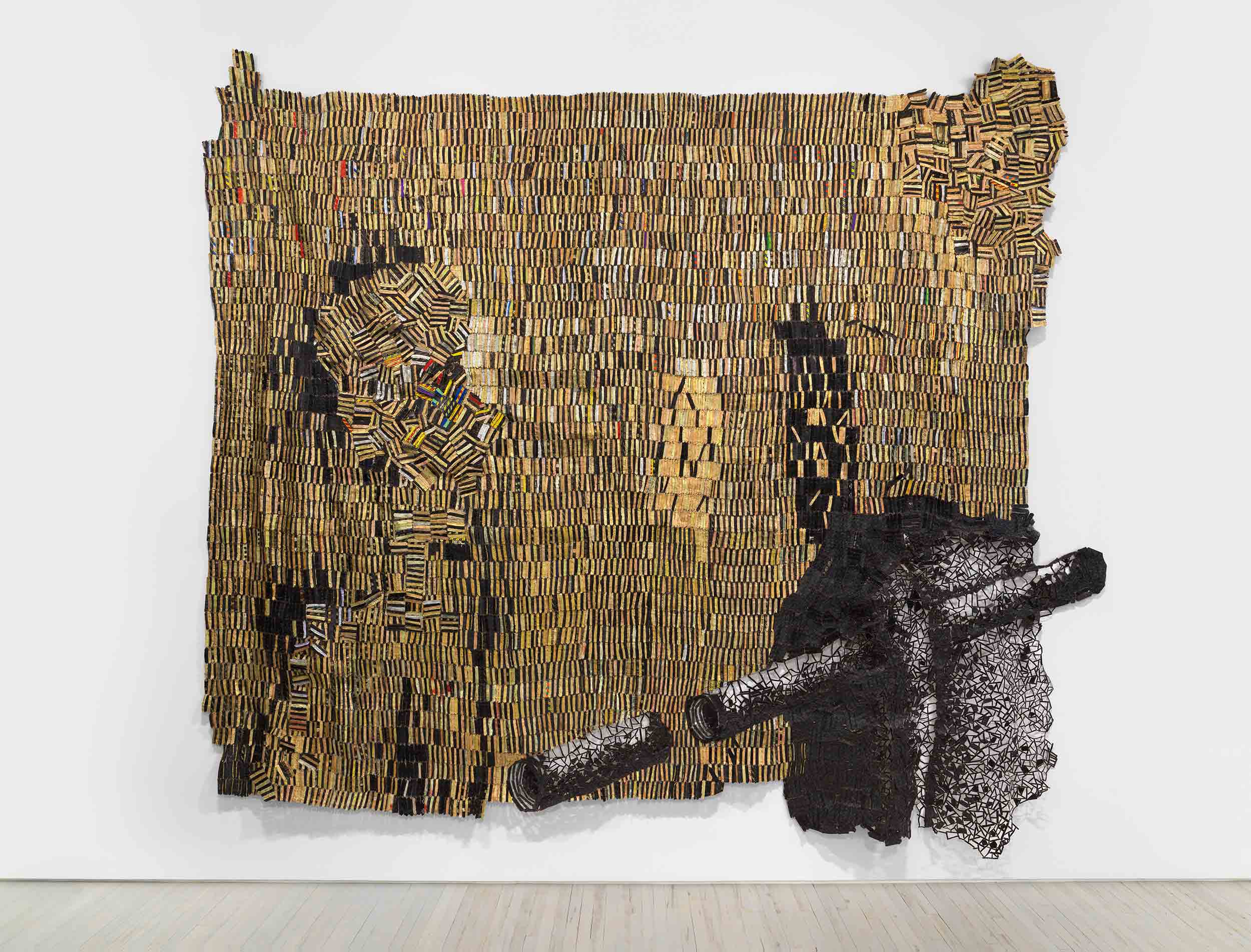

Spanning the building’s three levels, General Conditions is both formally and thematically nonlinear. One constant throughout, however, is a certain grandeur among many of the works on display. This is evident in Yoan Capote’s approximately 8 by 11-foot fabrication, Muro de Mar (Umbral) (2020), a dark, rolling seascape with hundreds of fishhooks and nails pierced into recycled wooden doors. What appears inviting from afar becomes verboten upon deeper inspection of its materials. In Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui’s 12 by 15-foot metal wall hanging, Obscured Narrative (2022), which manipulates copper and aluminum into a fabric-like quality, the transfixing sheet’s dark underbelly reveals itself in a closer look: the metal panel is made of flattened liquor bottle caps to depict an obscurely violent scene. There is a similar eeriness in Shannon Bool’s grayscale tapestries portraying Modernist interiors occupied by women’s bodies. At once captivating and ominous, Bool’s larger-than-life printed murals whisper a cautionary tale of modernity’s broken promises of freedom and progress.

On a smaller scale and most central to the exhibition’s title are Alina Tenser’s brutalist concrete meanders, and half-unzipped, colored vinyl sleeves. These sculptures refer directly to the idea of “general conditions” in an architectural context, the often intentionally vague governing framework required for a project’s completion. Shainman, who worked alongside Tenser to develop the exhibition’s concept, notes a dual “utopic and dystopic” quality about Tenser’s structures. Much like how many of the models and blueprints of the future we are shown today still feel sinister—no matter how “energy efficient” or “smartly designed.”

At large, the exhibition manages to address and then transcend the question of the purpose of art-making in tenuous times, going further by considering how we might confront such a state of affairs through art, and the ways in which art may serve not just as a reflection, but a recourse. Shainman shared that the curation process behind General Conditions was uniquely labor-intensive, but for him, it’s a labor of love. “I really enjoy thinking about the topic, how something relates to another, and juxtaposing artworks and how that looks or what kind of themes it brings.” This level of care permeates General Conditions, where the works speak for themselves, and also to each other, proving that in a world on fire, making art is possible, reasonable, essential.