For Document's Spring/Summer 2025 issue, the painter shares an unseen series of self-reflexive prototypes ahead of her exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum

Lisa Yuskavage’s triumph lies in the torque of her virtuosity. The painter often references herself within her expansive body of work, revisiting, recontextualizing, and reproducing poses and motifs as signatures at various scales. The themes embedded in the resolved surfaces of her paintings are only enhanced by a glimpse at their prototypical forms. Sketches: the means of anyone’s becoming. Even after painting for more than 30 years, Yuskavage’s sketchbooks contain the records of a practice perpetually taking shape.

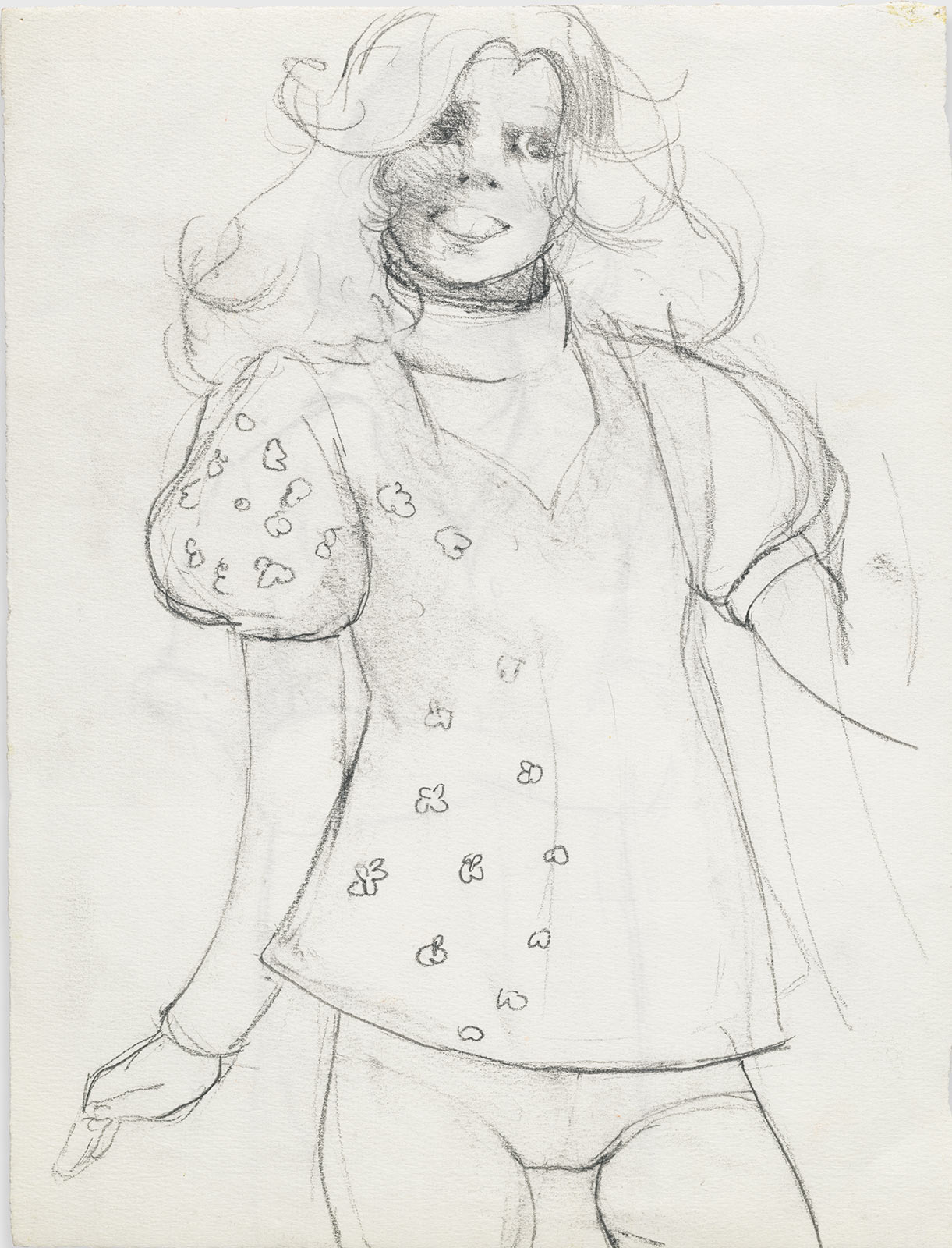

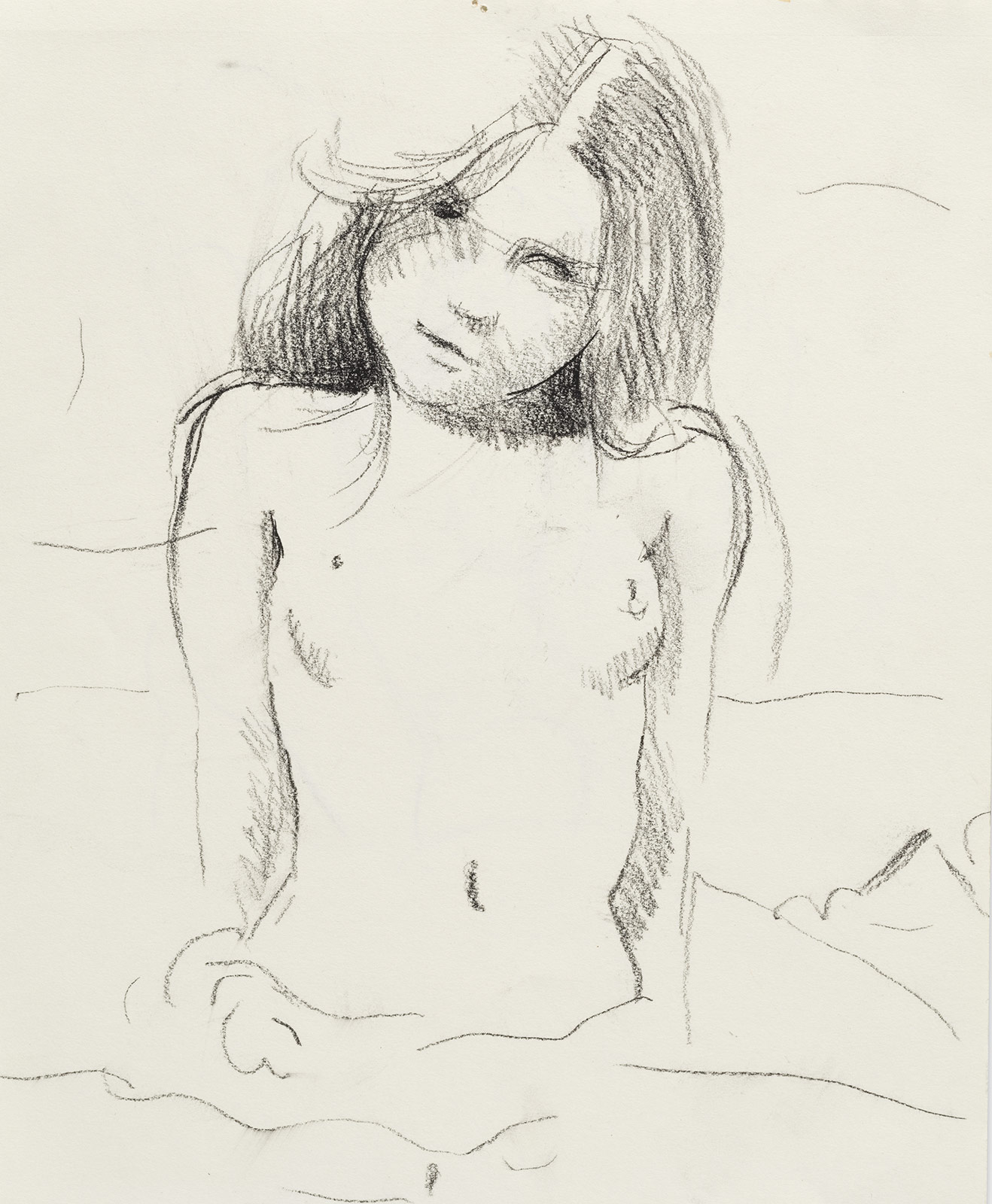

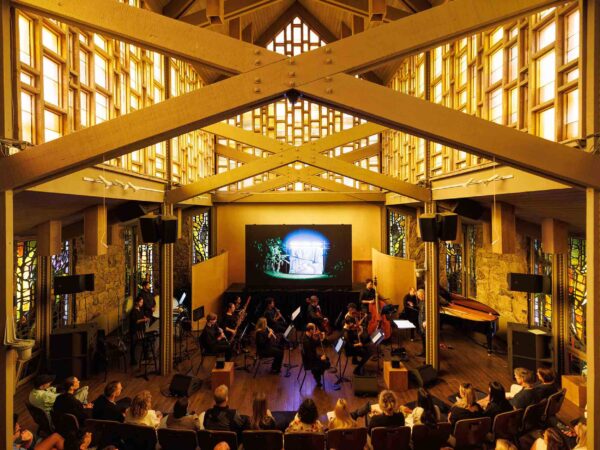

Yuskavage’s latest exhibition—at the Morgan Library and Museum on Madison Avenue until January 2026—arranges these fragile pages as the underbelly of her vivid universe. The spread provides a glimpse at the artist’s personal archive and process as she figures a conceptual frame for her feminine forms over the past thirty years of her artistic career. Among these sketches, studies, and small works on paper, Yuskavage develops a visual lexicon caught between the tradition of nude portraiture and more contemporary caricatures of the human form. The expressive bodies of Yuskavage’s subjects share a penchant for teasing the public imaginary. The painter’s subjects epitomize the feminine, and yet, their forms are uncanny, both for their surreality and their honesty.

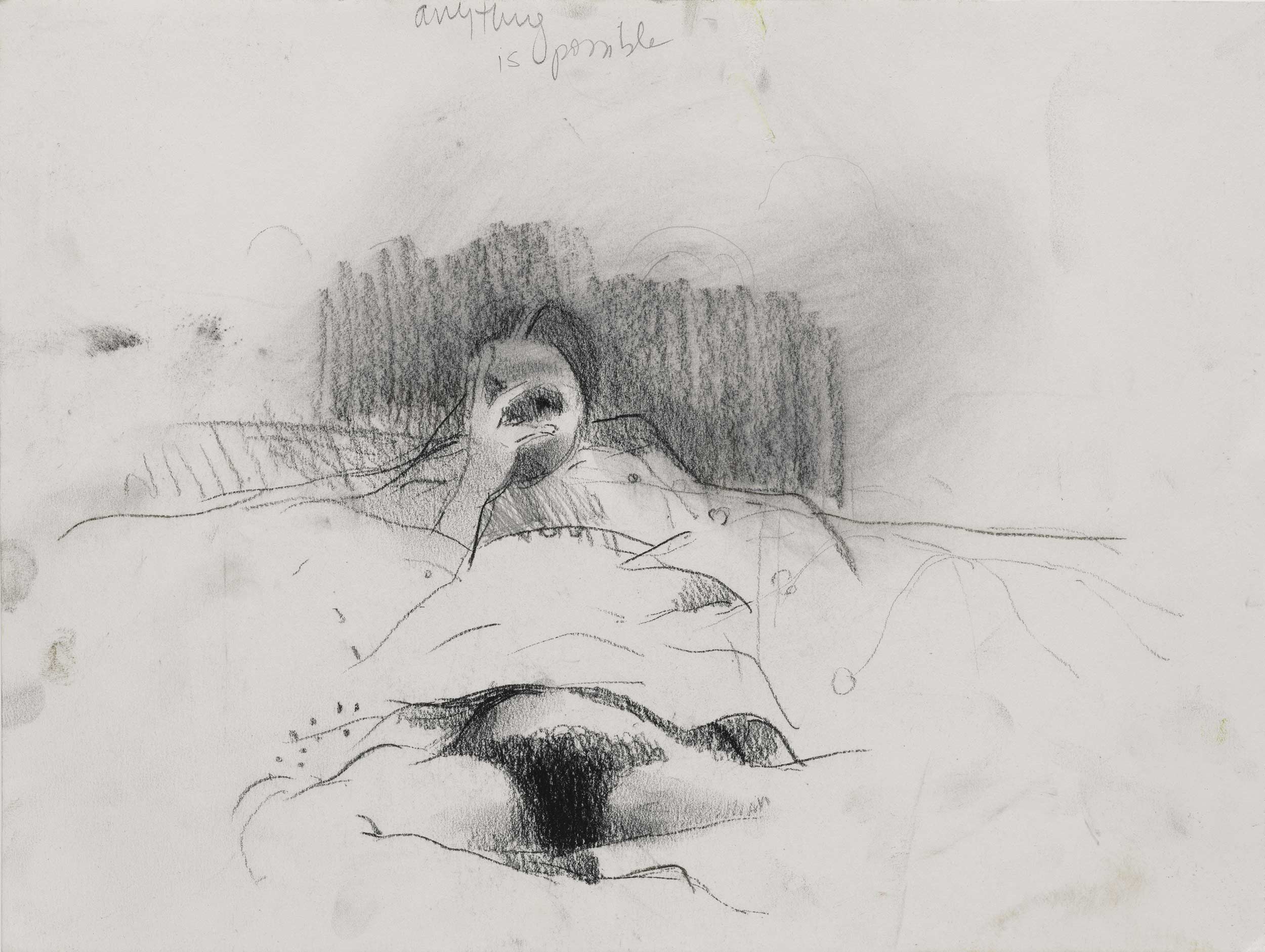

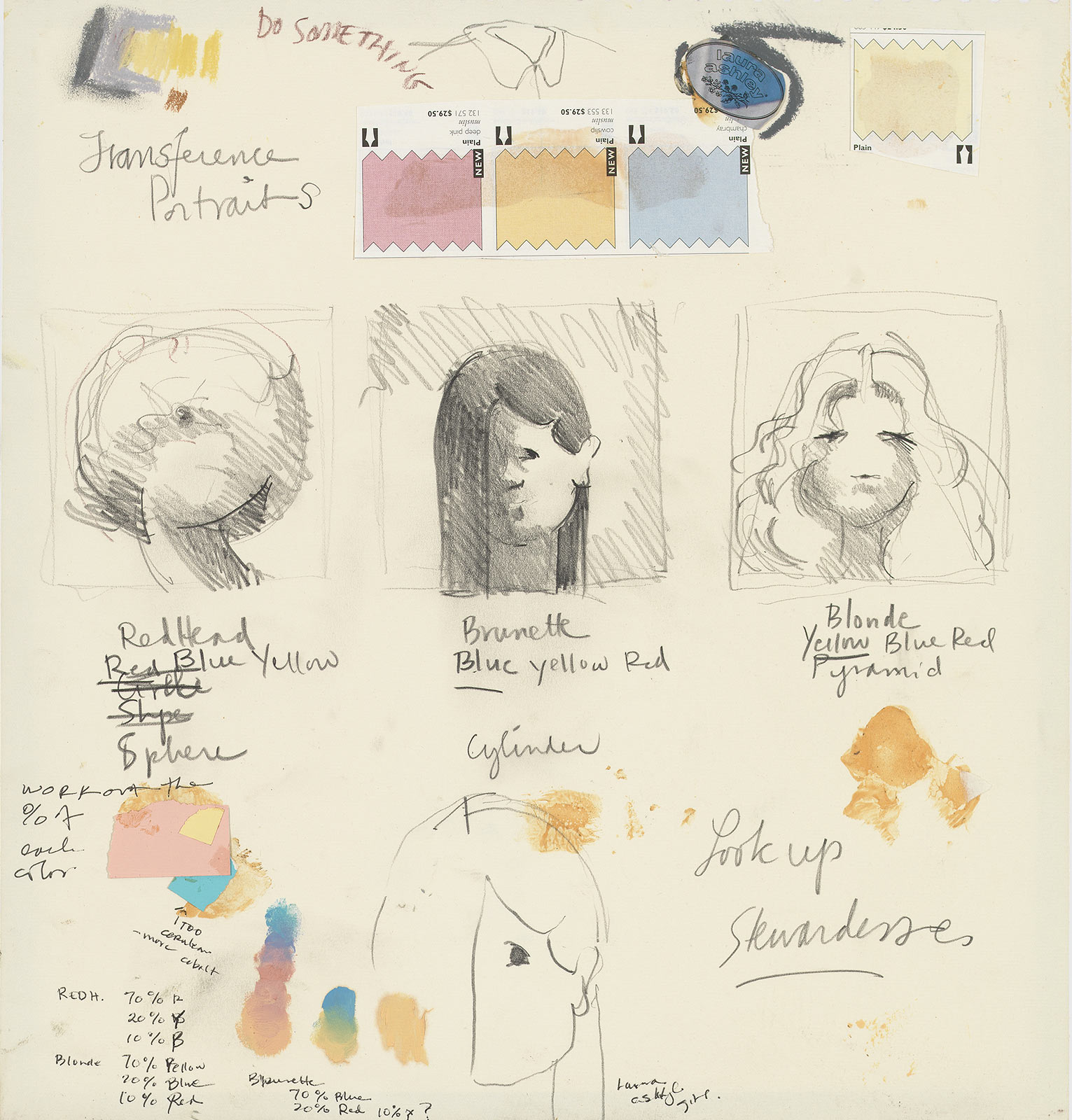

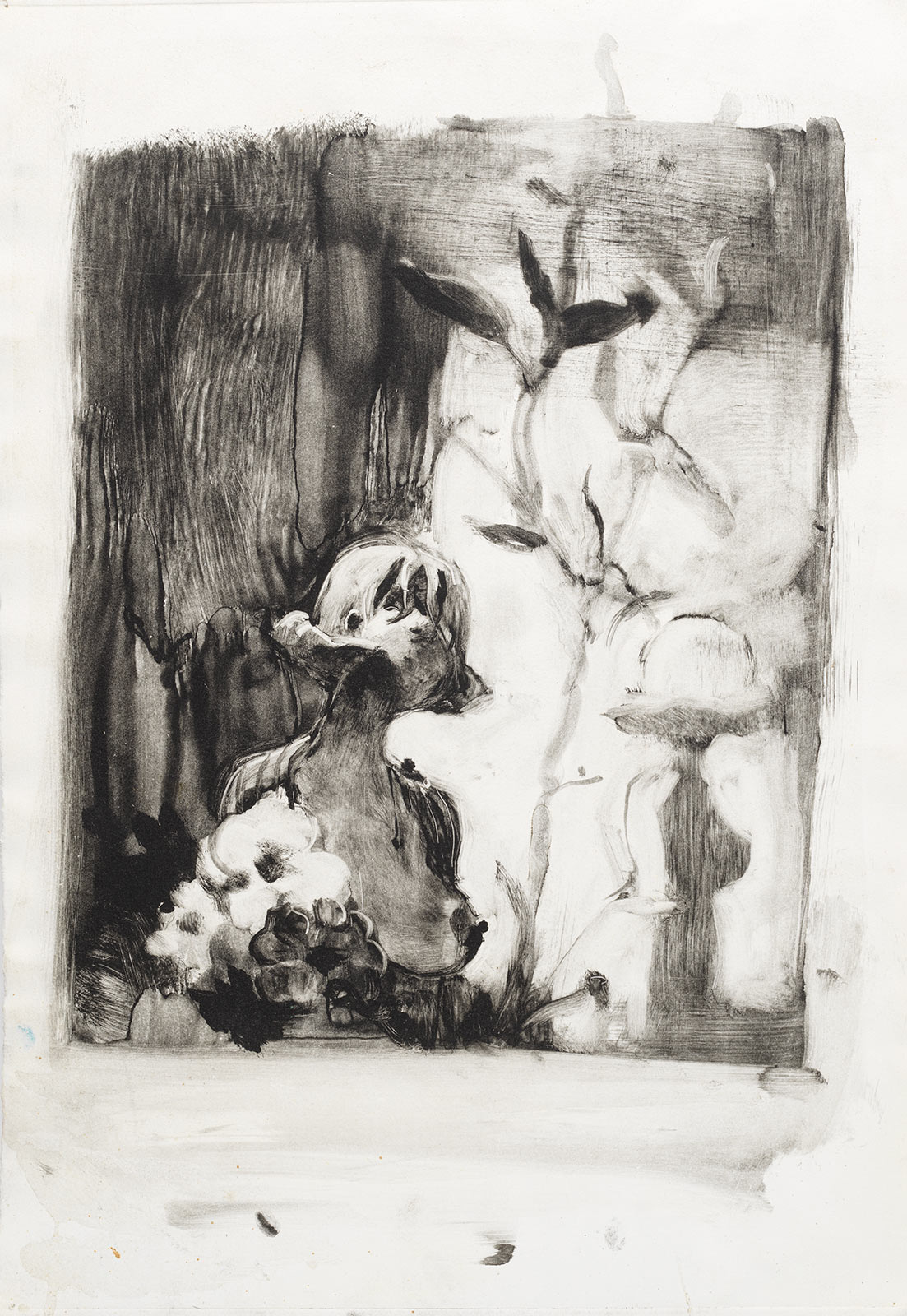

Yuskavage’s drawings are a series of experiments: in graphite, pen, charcoal, gouache, watercolor, and ink on paper. They’re her chosen tools in the search for the character of her figures. There is a certain satisfaction present in her figures’ faces—eyes gleaming and barely there. These faces are whispers, ambiguous and ambivalent visages unbound to the formal standards of her typical works in oil on linen. Her sketchbooks provide glimpses folded between confessional marginalia and the inevitability of failure. These are essential failures, the ones that take place in privacy. Half-images, eternally incomplete. The artist’s scrutiny is instead directed at the operation of her endeavors, techniques that concern the larger context in which these attempts are situated.

Yuskavage’s studies function as impressions, rather than expressions, of a central idea concerning the relationship between her subjects and the viewer. Her recent large-scale works often hinge on the function of a reflection, or the implication of the pictorial frame in the image itself. Her figures have a tendency to look back at the viewer, whether it be through a mirror or the rendering of the painter’s hand. The artist seems to take pleasure in this complicated gaze, formulating a meta-commentary on the medium of portraiture through silent eyes.

In the artist’s sketchbooks, however, these women appear primarily in relation to the artist herself. They look back intimately, into the memory of Yuskavage’s eyes. Through her sketchbooks, we begin to understand the relationship between the artist and her subjects, the temperament of the artist in-process. Cryptic annotations dapple corners like sigils summoning her forms. Iterations contest the value of a shadow. Traces of a palm’s edge smudge the curious planes of her pages. Yuskavage’s sketches present her practice in the slow temporality of themselves. The artist’s hand maneuvers past thought or language toward a pure energy, automatic and unflinching. What remains is a tether between the subject and her viewer, a line.