Following the two-week-long event, festival founder Sam Ozer chats with some of the creators behind this year's immersive exhibitions

TONO Festival, a celebration of time-based work, returned this spring for its third edition, taking over museums in Mexico City and Puebla with live performances, video installations, and film screenings. In addition to a screening program in collaboration with MoMA and New York film curator Sophie Cavoulacos, the program also extended to another outpost of films exhibited at the H Box gallery at CAM Gulbenkian, Lisbon. This year’s edition featured over twenty artists and collectives from around the world, drawing not only a largely young, local audience, but also notable attendees from Mexico City—such as chef Elena Reygadas and artist Damián Ortega—as well as international guests like Neue Nationalgalerie director Klaus Biesenbach and Whitney Museum curator Drew Sawyer, among others.

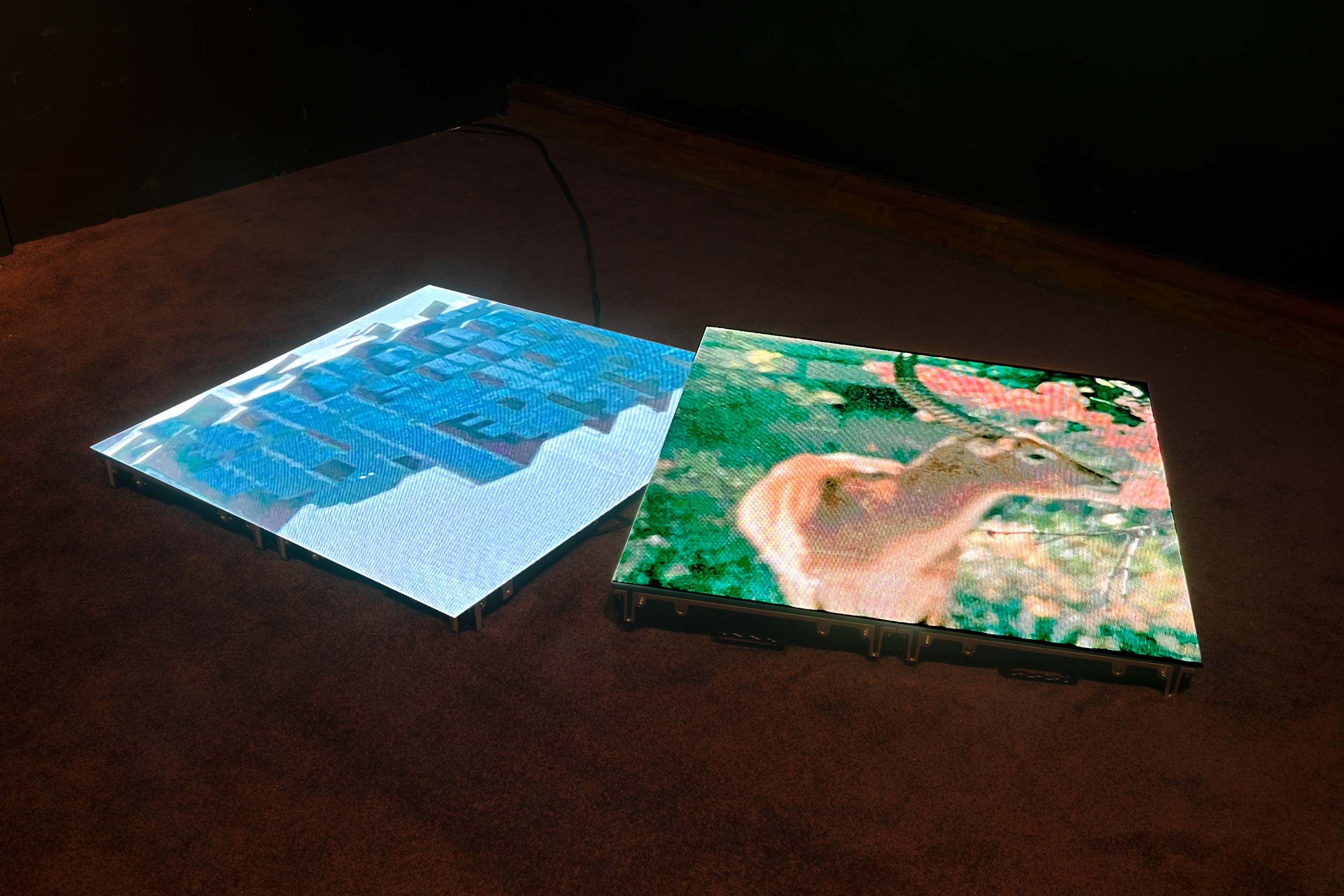

In addition to touring Adam Linder’s Mothering the Tongue lecture-performance, where he danced through a rumination on the practice of “free dance” to explore the connection between the body and language, TONO featured several new commissions that explored poetry, choral practices, and embodied movement. In Aguas Frescas, co-produced with MUDAM, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane’s band of collaborators proposed an expanded definition of poetry as a communal, durational, and sensorial act, inspired by the everyday Mexican performance of gathering to drink fresh juices. The transformation of words into form and the fluidity of natural cycles were present in Jota Mombaça’s Corriendo hacia la asamblea de las cosas, co-produced with Wiels, in which a chorus of local singers worked with Mombaça to reinterpret a poem of tides in the context of Mexico City’s water systems. Eartheater and Freeka Tet’s new video and live performance drew connections between human and shark anatomy—splicing x-ray images of a shark head and female pelvis against the heartbeat of the pregnant singer’s fetus.

A resounding chorus came together in Delia Beatriz’s performance which closed out the festival live program. Staged in her TONO commissioned multi-channel sound installation Sequedad Sobrenaturalizada (2025), the performance and exhibition responded to the history of the museum Ex Teresa Arte Actual as a former church and reimagined Carmelite and monastic choir traditions. The cyclical nature of time and themes of death and transformation were present throughout several of the exhibitions. Saodat Ismailova: Abyss Between Two Mountains at Museo Amparo brought together films, installations, and woven materials to explore the role of mountains within her body of work, examining them as the confluences between several continuums of time. Korakrit Arunanondchai and Alex Gvojic: Pray, Daniel Steegmann Mangrané: Drench, and Luiz Roque: Paradise, are solo presentations on view at Laboratorio Arte Alameda, another museum which was formerly a church, explore ghosts—of people, ideologies, forests, and architectural giants—and imagine the darker sides of paradise. Finally, Carolina Fusilier and Paloma Contreras Lomas: Cómo se escribe muerte al sur? at Museo Anahuacalli responds to the phantasmagoric imagination of the museum, which Diego Rivera created as a temple for art to house his collection of pre-Hispanic objects and where he hoped to be buried when he died.

As the exhibition program extends beyond the festival dates, Document spoke with several of the artists and some attendees:

“Both the verticality and cyclicity of time are present in Uzbek and Tajik classical poetry, as well as in local professional musical suites. This has often led me to think about possible narrative structures that do not necessarily connect with us on a mental or intellectual reading, but rather engage our emotional and sensory experiences, allowing us to explore intellectual perspectives from different angles. Let’s refer to these as nonwestern narrative structures, which, in my view, provide a space for the audience to engage actively, rather than simply absorbing predefined conclusions or directions.”—Saodat Isamailova, film director and artist.

“Media in this exploration of understanding spiritual transitions, became the mediums for connecting to the realm of ghosts or immaterial worlds that are not accessible through sight. Paintings are portals and speculative machines that transform matter, animate the inanimate, wake up the dead…”—Carolina Fusilier, artist.

“Since I started with my investigations I have built different categories of specters or ghosts—for example, political ghosts, economical ghost, and corporeal ghosts—to understand how these bodies that surround me are affected by these specters of the promise of modernity. Also living in the Third World, understanding not in the way of the 20th century, but more like the specter of living through and after capitalism. For me, specters have been an essential tool to produce my own imaginarium. I think of some of them like oracles because they are of the past and the present and what I imagine of the future.—Paloma Contreras Lomas, artist.

Songs for Living deals with the ocean as the space of death, where spirits and flesh rejoin. In this video the ocean is imagined as a womb for the individual whereas the fire becomes the womb for the collective to form around and to reimagine high powers. Songs become the medium that brings the spirit and the flesh both on the individual level and on the collective level, together. The video installation thinks through the emotional and transcendent impulses of peoples, nations, and beings living under the symbols of higher powers.”—Korakrit Arunanondchai, artist.

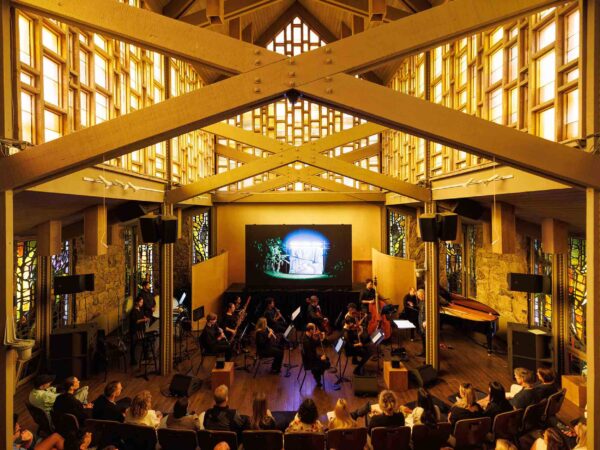

“For years I have pushed these live shows and concert formats to their furthest consequence while deliberately avoiding the label “sound art,” because I want to stay inside music’s own lineage. TONO offered the freshest and most contemporary context for this stance, and Sam’s holistic approach to production supporting not only the concept and music itself but the entire ecology of a live work, gave me the freedom to make my largest stride yet. That freedom allowed me to create a true Gesamtkunstwerk: I researched and composed for former Carmelite convents, re-engaging with the order’s musical heritage, and presented the resulting concert in the form of a mass alongside a live choir and 8 muses who read the meta-reflective liturgy. The project (Sequedad Sobrenaturalizada) builds on the long history of concerts, sound installations, and site-specific practice, treating architecture as a physical music, yet it reimagines those traditions for the present moment.”—Delia Beatriz, musician.

“Daniel Steegmann Mangrané’s work Drench (2024) establishes a poetic and critical dialogue with the Laboratorio Arte Alameda, a building whose history—from convent to cultural space dedicated to contemporary art—reflects an overlap of temporalities, uses, and narratives. The video, filmed in the replanted jungle of Tijuca, where traces of colonization remain, shows the image of an eye underwater surrounded by tadpoles as an apparent regeneration of nature. In a way, the work inscribes itself in the space that hosts and exhibits it, and both become structures traversed by memories, impositions, and re-significations.”—Lena Solà Nogué, Tamayo Museum Assistant Curator.

“With Paradise, Luiz Roque transforms the screen into a space of longing, memory, and possibility. Presented at Laboratorio Arte Alameda as part of TONO Festival, this exhibition reminds us how moving images can hold both personal intimacy and powerful social reflection.”—Abaseh Mirvali, Vienna Contemporary Artistic Director.