Meet the pair responsible for Sónar Festival’s daytime multidisciplinary programming ahead of the annual Barcelona electronic music festival

It’s 1994 and the walls are sweating in Sala Apolo, a club in Barcelona. Esplendor Geométrico is headlining, and their industrial trance has suspended the crowd in an elevated state of bliss. For those who have never attended Sónar, the Spanish festival dedicated to the intersection of music and new technologies, it’s easy to imagine partying to the beat of live techno music for three days. This is true, but only under cover of darkness. During waking hours, the festival hosts Sónar+D, a selection of innovative installations within the event’s daytime programming (Sónar by Day) geared toward the creative industries and digital cultures that inspire the kind of music patrons will dance to later in the evening. To adjust the image: It’s high noon the day of Esplendor Geométrico’s headlining show, and all the music heads, engineers, and artists alike come together at Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona for seminars, workshops, and exhibitions surrounding pre-eminent sonic technologies.

This symbiotic relationship—between day and night, technology and music—was a part of Sónar’s ethos from the very beginning. Founded by music journalist Ricard Robles and artists Enric Palau and Sergi Caballero, the first Sónar in 1994 was an intellectual riff on the events of a music festival. Alongside performances by musicians like Björk, Aphex Twin, Ryuichi Sakamoto, and De La Soul, Sónar by Day has hosted talks on the open music initiative, workshops on creative robotics, and Innovation Challenges, a showcase where “challengers” (tech companies in the creative field whose projects are pre-selected via a submission process) respond to an open question posed by Sónar, like how to optimize in-flight entertainment, for example.

Ahead of this year’s festival, Document Journal sits down with Sónar+D and Sónar by Day curators Antònia Folguera and Ikram Bouloum, the curators responsible for the diverse range of programming we’ll see in Barcelona.

Maya Kotomori: How did you both get interested in techno music and what led you to Sónar?

Antònia Folguera: I was introduced to electronic music when I was a teenager, basically through the radio—I heard some weird electronic sounds and I thought, This is something that I like. A few years later when Sónar Festival appeared—I think my first one was 1995 or 1996—it felt like I was entering a place where I felt at home. Little did I know that one day it would be my job to be responsible for a small part of the program.

Ikram Bouloum: I’ve always been interested in electronic music because you can see how the codes of a music genre can change over time. I started to be obsessed with the genre of electronic music—right now, electronic music is everything, but back then it was something more concrete. I used to research different types of electronic music, like PC music and deconstructed club. And somehow around 2013, these genres all started to be more focused on narratives. I’m also an artist and I started to go to Sónar as an audience and I played there some years ago. Like you said, it felt like home. I’ve also been a part of different collectives in the city. I’ve created my own parties in different venues. In 2022 after the pandemic, I started to work with them as one of the music curators, the one in charge of the music program for Sónar by Day, more specifically.

Antònia: I started to work here 11 years ago, when Sónar+D was only one year old. They were looking for somebody who specialized in digital arts and culture. Basically it was what I had been doing for the previous 20 years in radio and TV, and also belonging to many collectives that preach electronic music, audio/visual arts, and digital arts, but also internet activism.

Maya: Within your roles as a part of Sónar’s day programming, how do you curate that sense of home you both mention?

Ikram: I would say there are two key ingredients: one is hospitality. We really care about not only how the audience experiences the part, but also the people that come to work at our festival—we want them to have the best experience. On the other side, I would say that for us, the concept of the festival is a space that has to be taken care of, and we all have to work together to make each festival the best experience ever.

On the creative side, I would say that apart from me and Antònia, there is also Enric Palau, one of the directors of Sónar. We represent different generations with different backgrounds, and we have a lot of discussions because it’s so important to remain connected when the festival has a duration of three, four days. We have limited space, we have limited slots, so what we select is so important.

Antònia: I totally agree with hospitality, because Sónar is big, but it still has a human scale. You don’t feel super small in there. I think that helps as a festival goer. In terms of programming, I think that the fact that we are from different generations and different musical backgrounds means that that diversity can be represented in different ways. Sónar works as an aggregator of audiences, meaning that our range of music is very wide: you can have something that’s very mainstream, very dancefloor oriented, and then you can have a group of niche artists doing really intense, strange, and futuristic stuff. The audiences of these two types of music might not be connected during the year, but they have a festival in common. That’s Sónar. We invite audiences to take risks when they’re in a familiar space.

Maya: I’m curious about this concept along with The Independent Movement for Electronic Scenes aka TIMES. How did Sónar first get involved with that cooperative project to bring all these festivals together?

Antònia: We came together in 2016 under another name, We Are Europe. Basically for these festivals, we were all co-curating our content. That experience made us realize that together, we could do things that we couldn’t do by ourselves as individual festivals. Collaborating with others expands your knowledge, expands your horizons, and you start incorporating things that you otherwise wouldn’t think would fit your festival. We decided to apply for a third time because this project is funded by the European Commission, and under the name TIMES, we’re able to create these interdisciplinary artworks where we put artists together, but also people who aren’t necessarily artists to develop something that’s interesting from the art-entertainment point of view, but also something with a discourse and idea behind it.

Ikram: With TIMES, we will be developing three individual projects, one each year until 2027. We will also be co-curating part of the musical program for each festival. It’s quite a privilege to have this space to be with the other nine curators from other festivals and be able to share ideas and perspectives.

Antònia: There are many, many electronic music festivals that only put the focus on the fun and how much revenue they generate. For us, the fun is important—of course—but so is taking care of each and every artist that we choose, and choosing great artists, discovering great artists that nobody knows yet. They are not ticket-sellers but one day may become them.

Maya: What do you think is the most exciting new venture you have this year with Sónar+D?

Antònia: It’s always exciting because of this very disruptive thing called artificial intelligence. [Laughs] In a way, it reminds me of electronic music in the ’90s where, like, every six months there was a completely new and mind blowing genre. With artificial intelligence, every week, or every 15 days, something new and exciting appears not just for art and music, but for society, whether that’s good or bad. We’re working in a new landscape and what I think is exciting for this year is talking about breaching disciplines—we’ve brought dancers and choreographers as well as authors to the program. We have three writers and researchers whose work speculates on the future of things with fiction. We invited them to our conference not to give a keynote, but to tell a story on a proper musical stage with a sound system and lots of screens to share the visual side of the narratives they’ve written. I’m very excited about that.

Ikram: We create several connections that didn’t exist in the past that now are happening in this festival. I feel like we are not aware of how many connections we will have made in this edition. I’m sure this will end in several other projects that will add some special narrative at some point. For me, this is quite magical. Having the space of Sónar gives us the opportunity, not only of imagining which artists represent the culture of not, but also of this cross pollination that will build many bridges to the following year.

Antònia: Every day we will have more artists who champion imagination and break the mold. It’s beautiful.

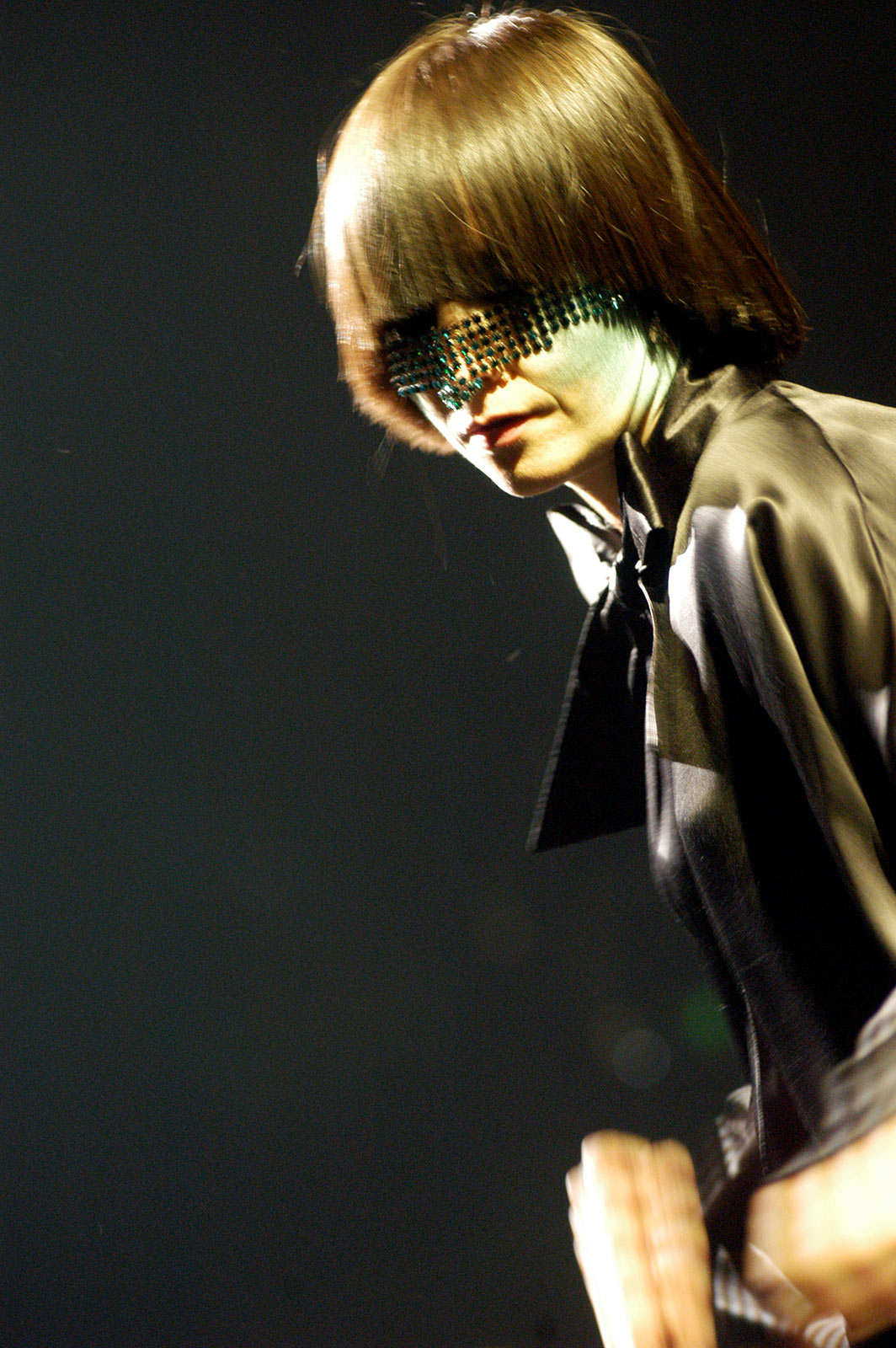

Miss Kittin at Sónar de Noche 2000.

Left: Sónar 2000. Right: Björk at Sónar de Noche 2003.

Chicks on Speed at Sónar de Noche 2000.

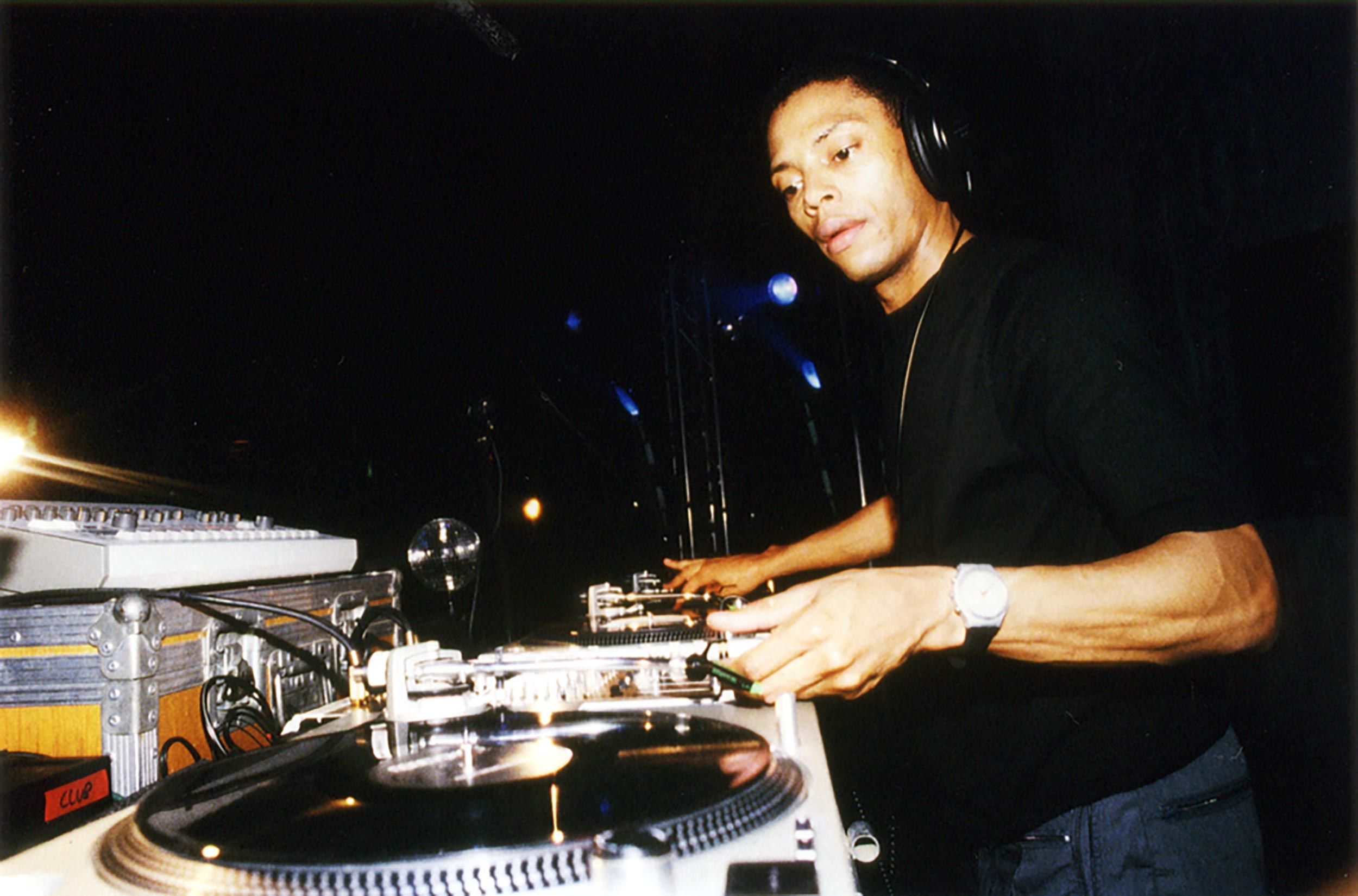

Jeff Mills at Sónar de Noche 1999.

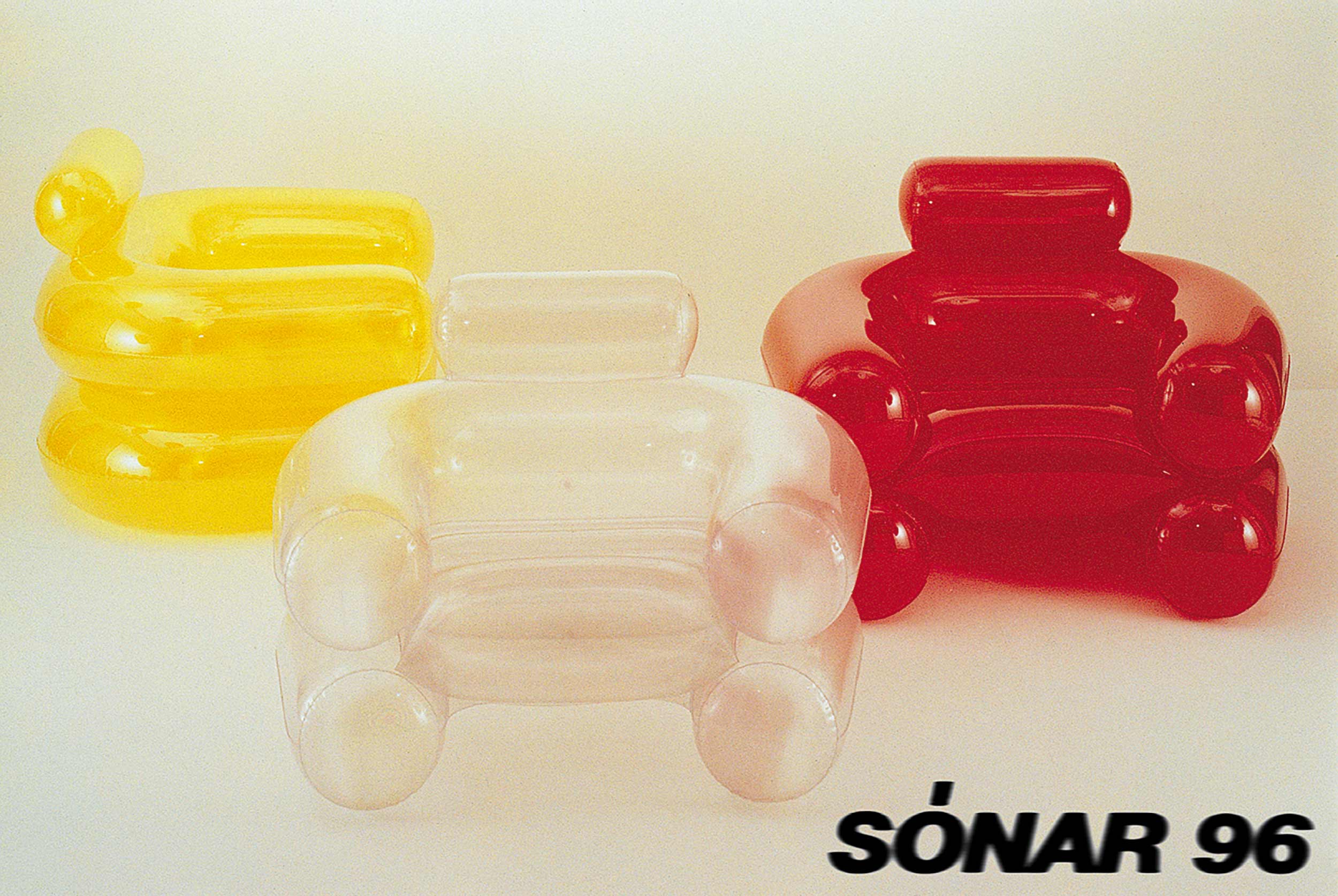

Left: Sónar de Día 2001. Right: Sónar 1996.

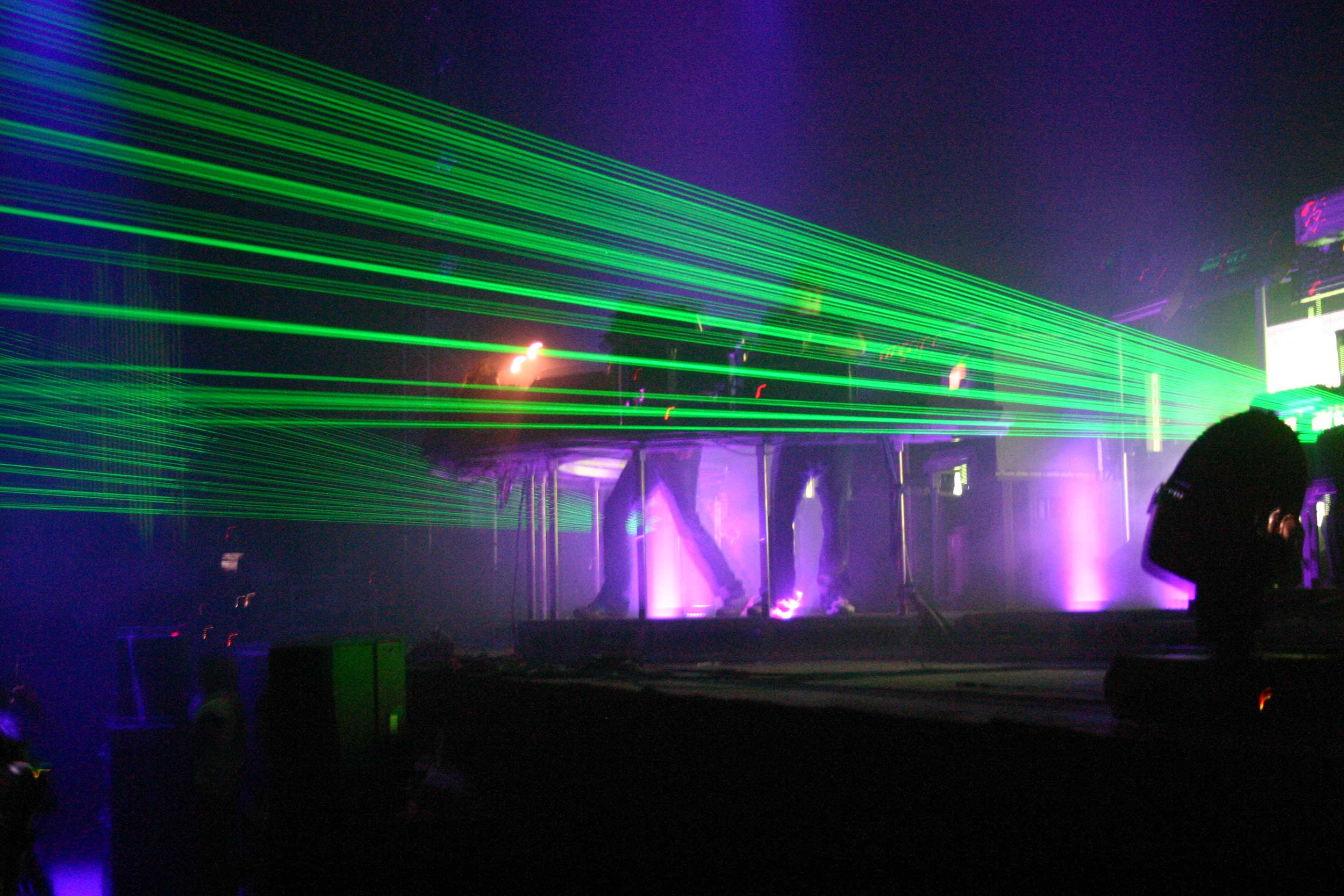

Richie Hawtin at Sónar de Noche 2012.

Left: Berkovi at Sónar 1999. Right: Grace Jones at Sónar de Noche 2009.

Sónar de Noche 2002.

Left: Carl Cox at Sónar de Día 2003. Right: The Chemical Brothers at Sónar de Noche 2005.

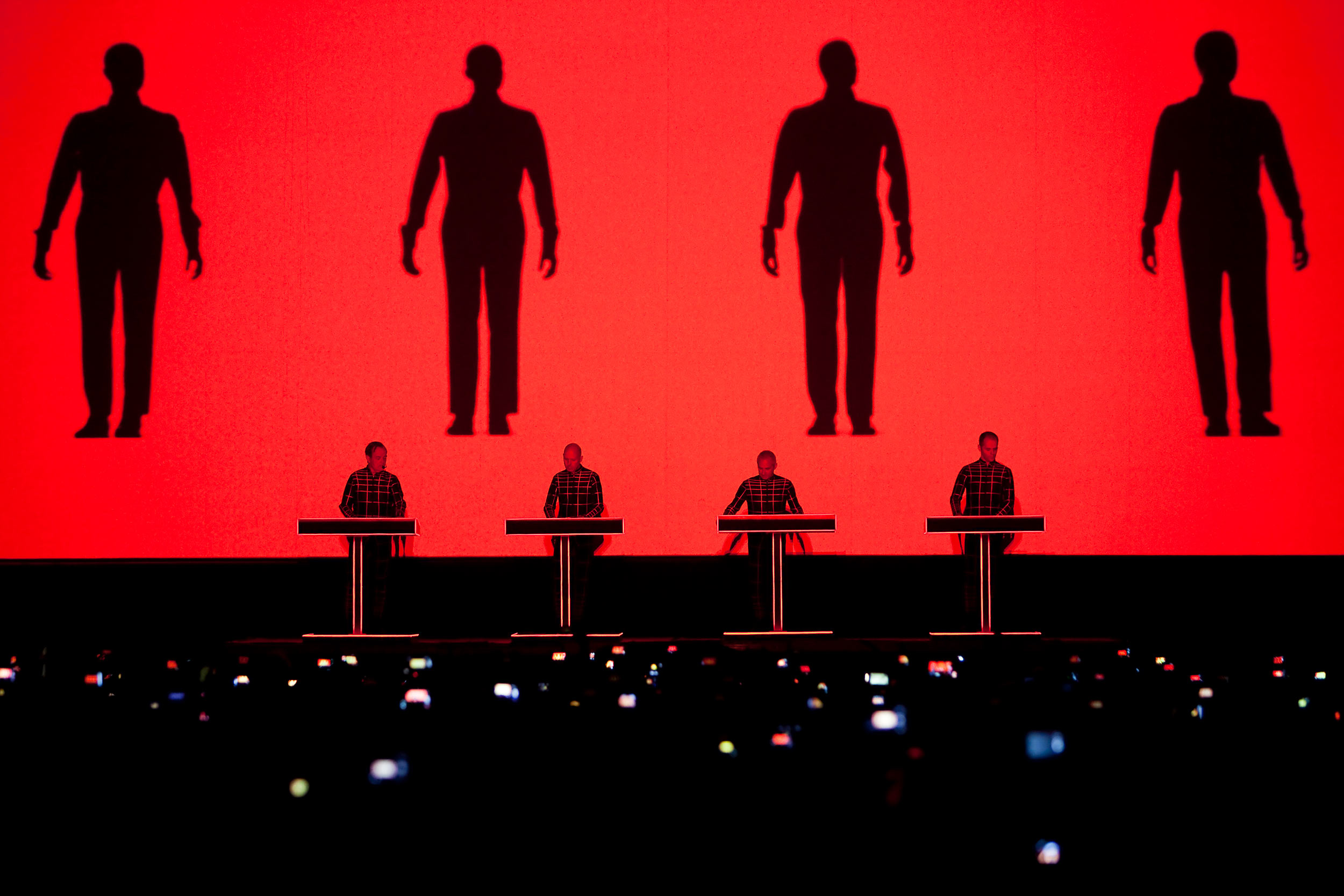

Kraftwerk3 at Sónar de Noche 1999 and 2013.

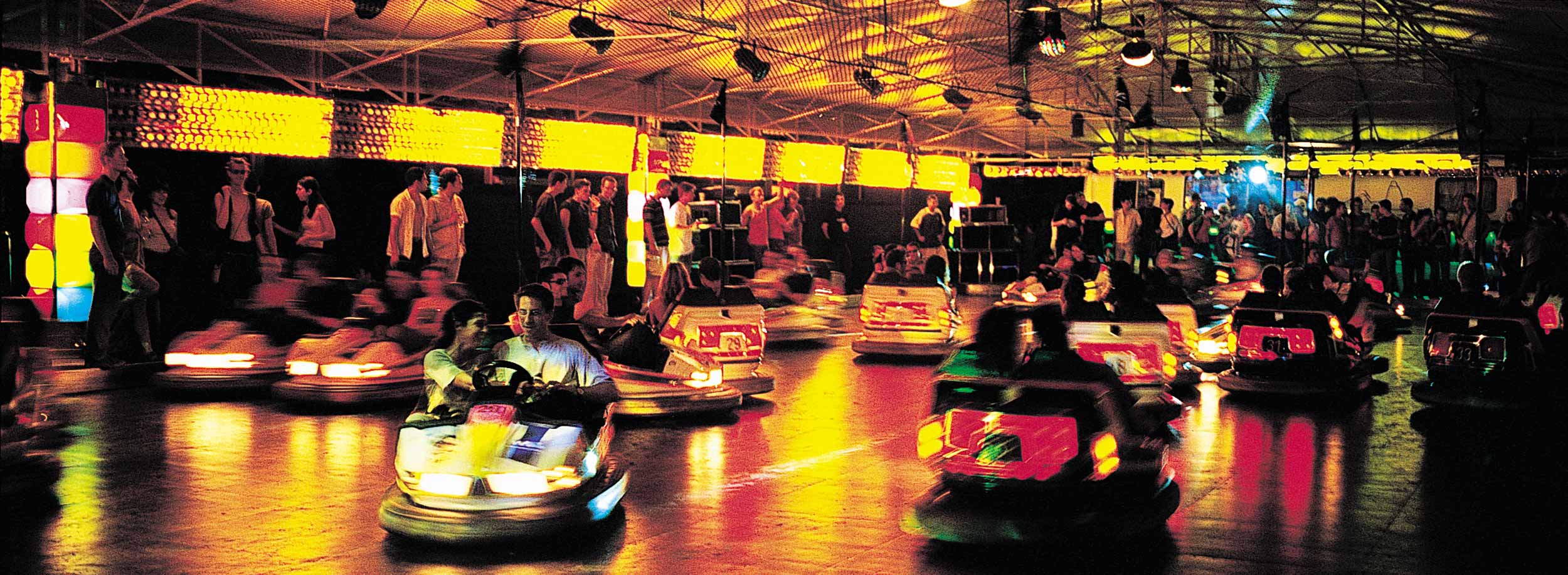

Sónar de Noche 2001.

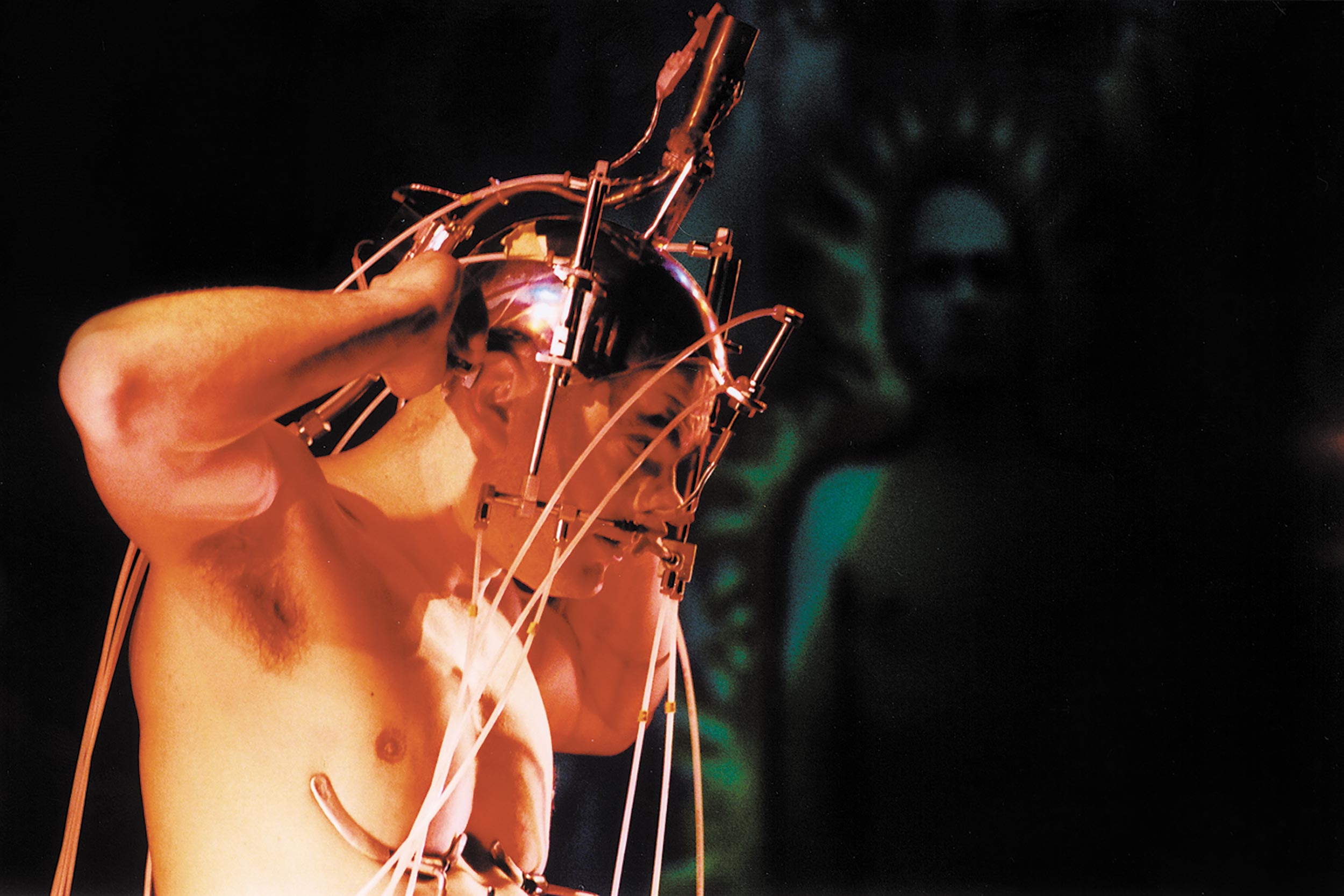

Left: Sónar de Día 1996. Right: Esplendor Geométrico at Sónar de Día 1994.

Nicolas Jarr at Sónar de Noche 2012.