At Lower East Side gallery Diana, two artists explore gay lust, pleasure, and the power of lewdness

The 12 drawings on display at Diana reek of testosterone. Here are horned-up men who want nothing but to surrender themselves to each other’s mouths and penises. They’re the occasional muse for two artists whose pairing seems apt if not downright convenient: Jimmy Wright, the 80-year-old painter of smoldering sunflowers, and Christopher Culver, the 38-year-old artist most known for dusky depictions of urban limbos. Both are gay men with a penchant for melancholia and a soft sentimentality, which color even their crudest exhibition of sexual debauchery in JIMMY AND CHRISTOPHER, on view until March 24. Yet sex itself isn’t what quickens the pulse of this small but superb show. It’s desire and the desperate need to satisfy it.

In the early ’70s, Wright started documenting New York’s cruising scene, specifically anonymous sex in the toilets of movie theaters and subway stops, which would withdraw into the shadows at the dawn of AIDS. But his drawings evoke a time when sex felt ripe only with promises of engulfing rapture; even the cruelest infliction of pain could be a turn-on. In this portfolio, that looks true for all but prudes. Nine-to-fivers blow leather boys and hairy hippies alike, while some Inspector-Gadget type screws one Castro clone after another. Each figure seems to stand for something—class, motive, burden—before their differences all but melt into roiling puddles of bodily fluids.

Culver’s cult of sex is something else altogether. Two Farmers (2024) shows a man laying on his back, his head hanging over the edge of a bed, as he chokes on a Coke-can erection. The raised veins on his neck bulge like deep, spreading roots, as if brought to life thrust by thrust. His submission, however, strikes one as romantic. At the secret heart of this image is an emotional warmth, a focus on the twosome, a tolerance for tenderness, and a belief in familiarity if not intimacy. It hardly matters if the man beds a stranger, for he knows him the moment he tastes him.

Both artists revel in the sheer filth of sex. But their titillation soothes rather than provokes. Perhaps when the rest of the country still saw New York as a sewer of vice and crime, sleaze was a brazen, transgressive attack on propriety and homophobia. Perhaps when gay liberation meant sexual liberation, before AIDS and a doting on monogamy after the advent of marriage equality, such lechery was freeing. Perhaps at one point the explicitness was radical—today it is orthodox. Progress, plus all-around gentrification, has more or less scrubbed gay erotica clean of any subversive shock. Without that, though, the idea of promiscuity indicates an expression, rather than a reaction, something sturdier, more honest.

Wright has no use for any pearl-clutching anyway. Nor does he seem to need beauty in his pen-to-papers. The artist may even be at his most riveting when he went right for ugliness. His best marks are jerky and lawless, their hostility yanked to the seedy vulgarity of his images. They make a mockery of a certain rigor, as though it rudely intruded on their fun. In Movie House Toilet #1 (1973), for example, no more than a squiggle describes one cruiser, save for his distinct hard-on, complete with a trail of inky hair, the shaft prodding straight out of a glory hole into a wet mouth. But memories of sex are often selective that way. With Wright, to pick and choose is to romanticize, to discern the grotesque and to render it in the fondest way possible.

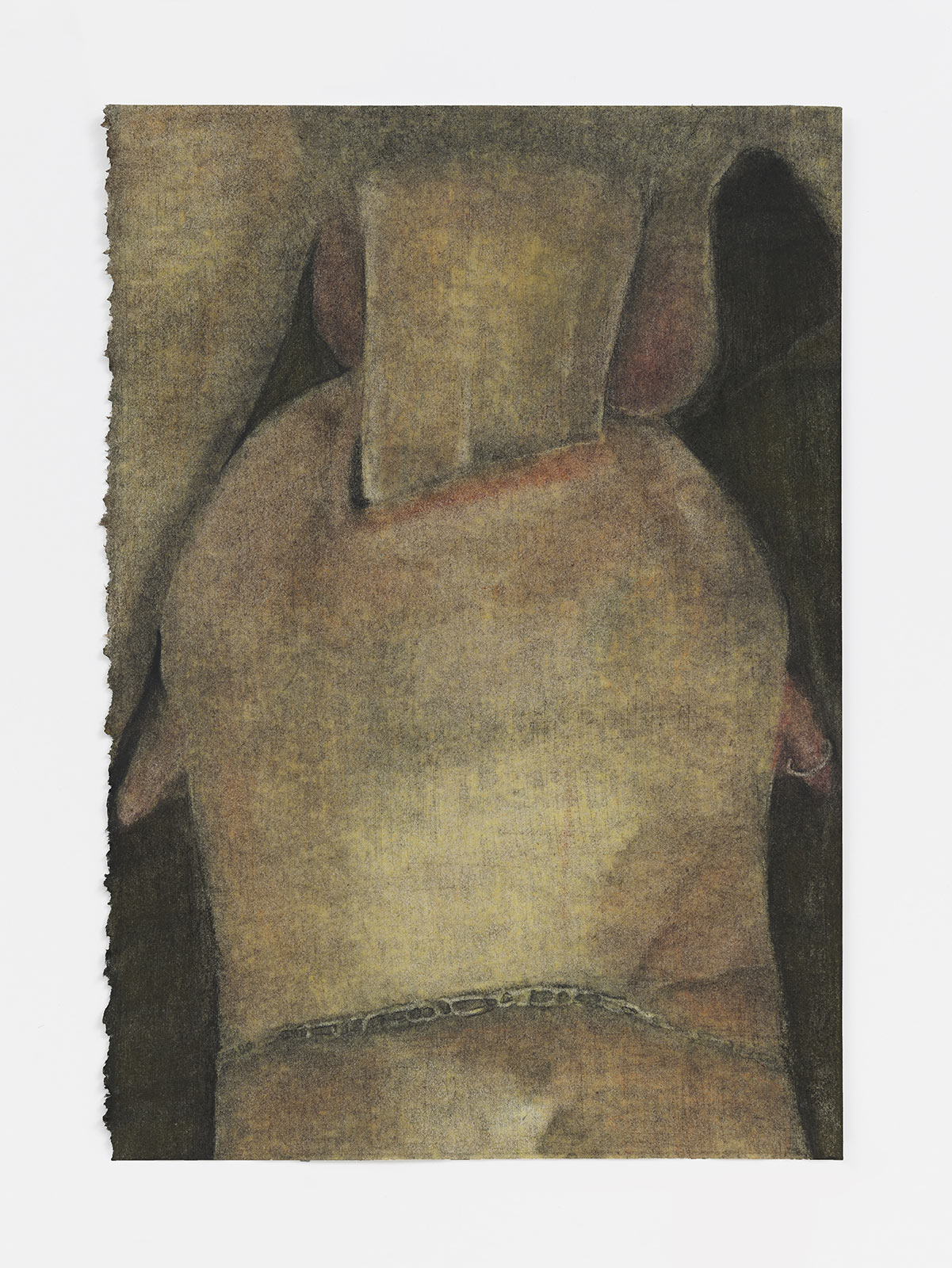

Culver is more taken by moments thick with all-encompassing emotions. Subtle variations of blue and green, bruised sporadically with cool browns and black, flood his drawings with a deep sadness. They want to know: How does one cling onto that post-sex high, here one second, gone the next? One answer is embedded in Farmers in the City (2024), featuring two male figures, both nude, in front of a mirror. One holds a camera, while the other gives him a kneeling blowjob, capturing the moment before it becomes a memory, when lust will once more be a dryness at the back of his throat. Their sex tape bathes in the oils of Culver’s gorgeous pastel and charcoal, which he exhaustively layers and erases. His approach feels at once gentle and forceful, inching Culver a little closer to Wright.