The art adviser-slash-curator challenges time and the solo-show-industrial complex in his latest show, ‘A Modern Disease—like jetlag’

Art adviser and curator Cooper Brovenick’s disarming sincerity is, like art, simultaneously material and immaterial: physical in his outreached hand offering me a glass of wine during our gallery preview, impalpable in the way he explains the concept for his latest exhibition, A Modern Disease—like jetlag.

The title of the show is actually a line pulled from a poem by the late Glenn O’Brien—Purple’s former Editor-at-Large—posthumously published by his wife for the magazine’s love issue. “I was thinking of other modern diseases, and I realized they’re all about time,” says Brovenick. Closing this Saturday, A Modern Disease—like jetlag is itself preoccupied with time’s collapse, housing five paintings, one triptych (by Sabine Moritz no less) and one sculpture from artists all in different stages of their career. “My definition of the modern disease is based on the idea of how people are always professionally chasing something that they won’t achieve—it’s all about fastness in the chase, but because we never get there we’re constantly at a lag.”

He chose the right location for a timewarp: the pale oak floors and white French windows of the Tribeca walkup A Modern Disease—like jetlag is shown in carries the glamor of a European townhouse from the ’50s. “I love that this space feels like looking at someone’s personal collection in their parlor,” Brovenick muses. The domestic setting—a friend’s home—makes sense for a curator who got his art world start by selecting work for the high-profile clients of his early mentor, interior design legend Whitney Robinson. A Modern Disease—like jetlag is his second presentation as a curator, a show that is a part of Brovenick’s larger nomadic ethos for his practice: He doesn’t have a gallery space, nor does he represent any artists as a more traditional brick-and-mortar gallery might. “I hesitate to call it a ‘pop-up,’ because it makes you think of, like, matcha,” Brovenick confesses. “Gallerists invest in artists throughout their career, where the goal is to build their profile, get them in institutions, all of that. Me not being a gallerist who owns a space means I have to do something different.”

For him, “different” means a point of view antithetical to the solo-show-industrial complex, a system based on a revolving cycle of young artists who earn gallery representation and the opportunity to develop their own show concepts only to disappear altogether. “What I think is interesting about a group show is the ability to put artists of different experiences in conversation with one another. My whole shtick is that I build my group shows around very successful late and mid-career artists alongside emerging artists to show a range of interpretation,” he says. “Galleries want to give their artists the opportunity to test things with their support, and that’s great! I do think that sometimes there’s too much space and too much pressure for artists though.”

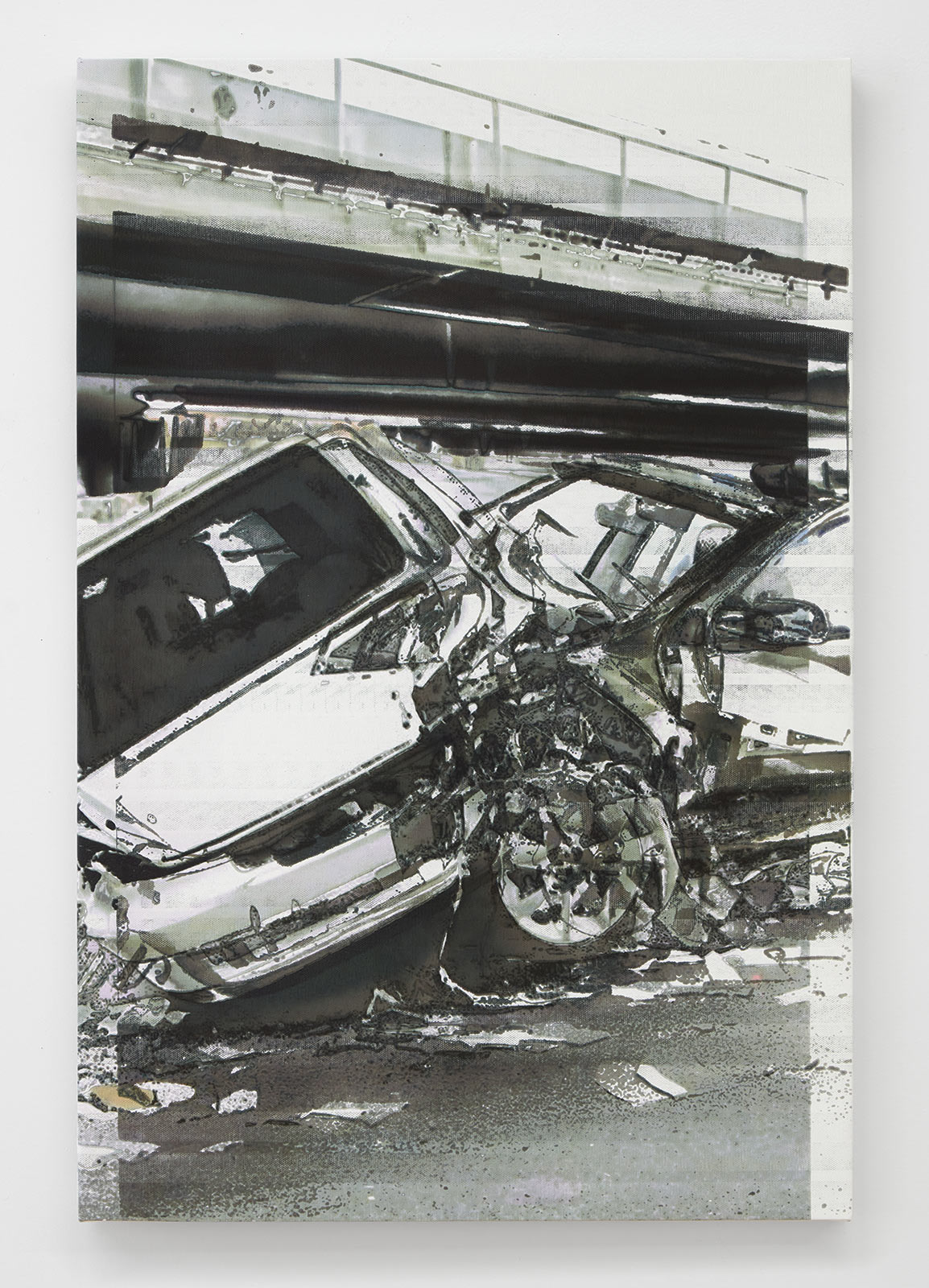

Brovenick’s references for A Modern Disease—like jetlag are as deliciously out of left field as they are myriad. He draws from Paul Virilio’s concept of dromology, or the theory that successful societies—as they are defined by wealth, political power, and a strong military—are built on ever-increasing speed. To Virilio, all instruments that increase momentum are intrinsically valuable to humanity; to Brovenick, art is its most disruptive when it is slow. A Modern Disease—like jetlag challenges dromology by showing how speed fails. Thomas Blair’s Study for White Car Crash, a 30-by-20-inch inkjet study of a grisly highway accident suspends a moment of vehicular impact on canvas; the image shows cars torqued to unrecognizable clumps of metal and burnt rubber as the consequence of freeway speeding. Beside it is Julia Wachtel’s Time and Again, a 5-foot-tall painting of a man in something between a space suit and contagion gear—glass fishbowl helmet and all—facing an alien-esque prehistoric figure. The painting reads left to right in three parts: half of the quarantine-suited man in black and white faces himself, this time painted in full-color in the center, facing the figure on the right. When the man looks “forward,” from black and white to color, his two-dimensional profile faces the right; the last figure, however, is painted to look at the audience, as if to challenge a two-dimensional idea of what looking “forward” means by breaking the left-to-right sequence.

“Listen, artists are cool because they will always be curious,” says Brovenick. “Later career artists get pigeonholed into the solo-show-industrial complex too. Thomas is one of my friends, and I put him next to Julia Wachtel, who’s very known within these art institutions. Curious artists can [and should] be in conversation with each other.”

The opening for A Modern Disease—like jetlag is effectively a house party. A group of well-dressed art and art-adjacent people meander about the space, chatting with their contemporaries about the works and the weather. They hold white wine packaged in those Japanese soda bottles with the jingly glass ball in them, and eat catered sushi arranged on the gallery floor, which is covered in bedsheets. Brovenick sits among the throng, cross-legged, in look 27 from Loewe’s spring 2024 menswear collection, grinning into a spicy tuna roll. Among the art, time becomes effusive, almost non-existent apart from a glimpse of the darkening sky. “What time is it?” asks a bottle redhead in full Simone Rocha before bursting into laughter. Everyone smiles—we all know it doesn’t matter here.