The artist’s latest exhibition demands connection between painting and viewer

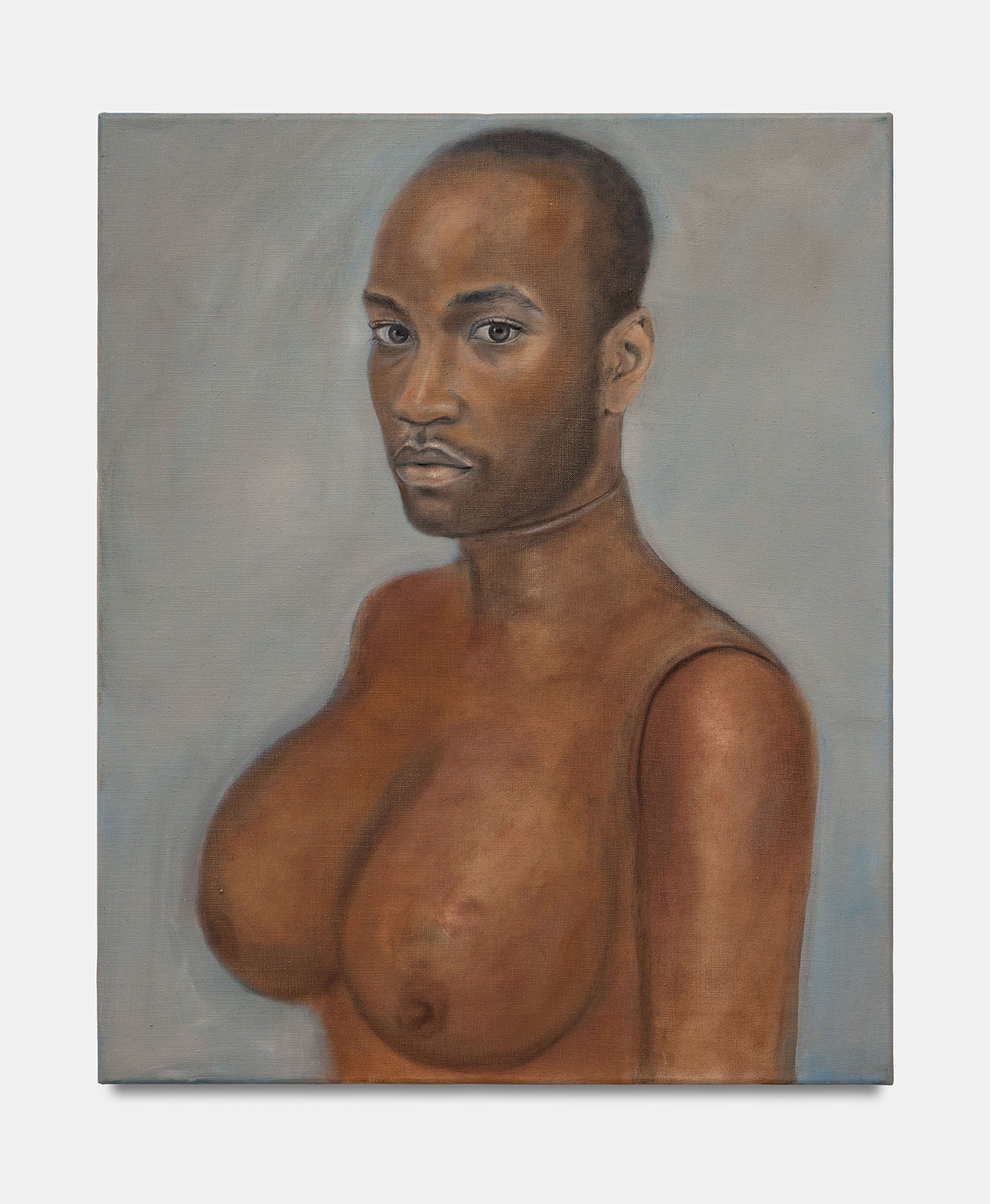

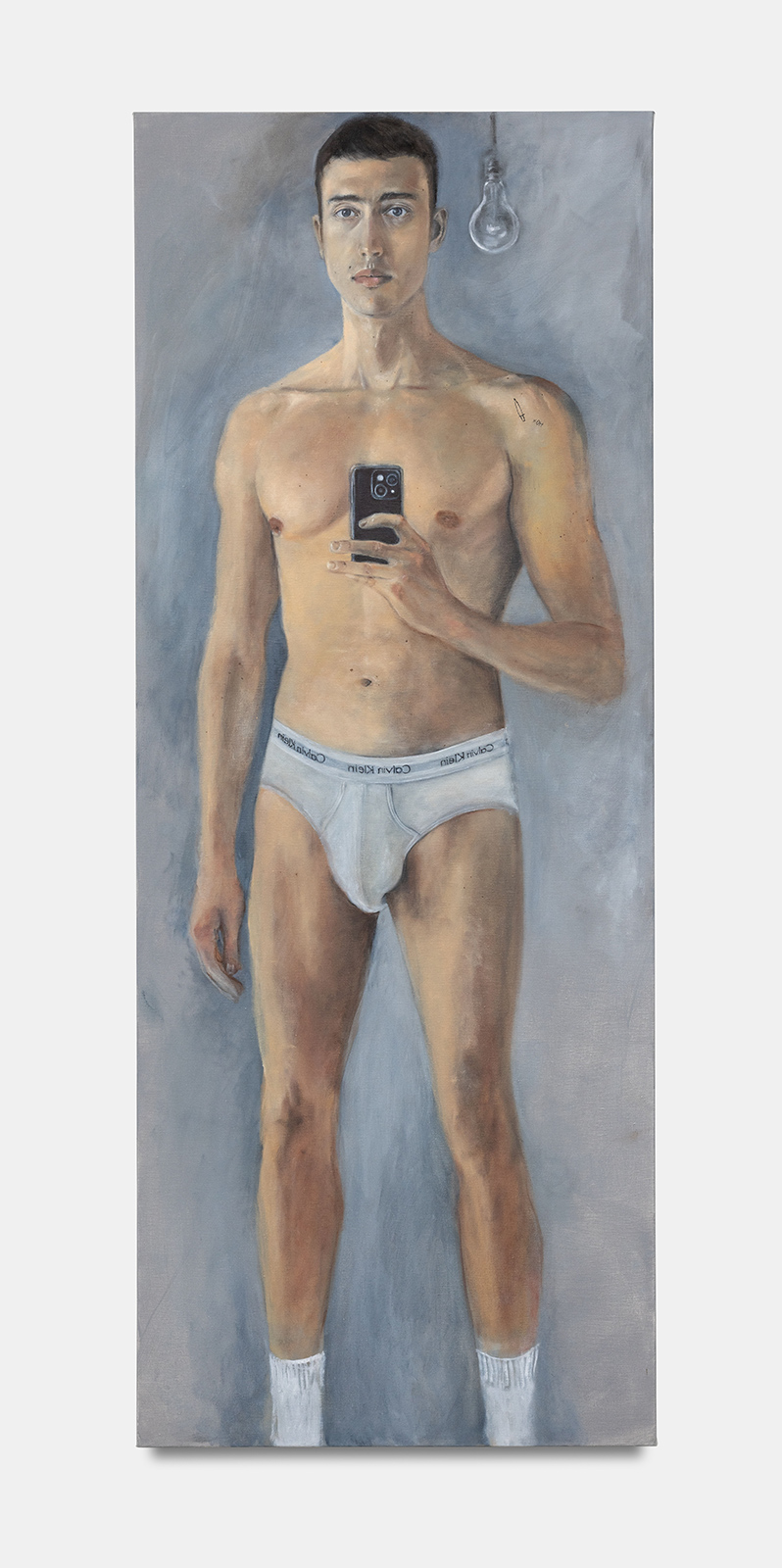

Cédric Rivrain’s portraiture demands connection; wordless connection between individuals. Presented with the Parisian Fitzpatrick Gallery, the French artist’s first American solo show titled Poussière is on view until March 3rd in a Hollywood Hills bungalow. Each of his subjects stare out from the canvas, making unbroken eye contact with anyone willing to meet their gaze. Suspended in time, the viewer is forced into a private moment with the stoic figures.

The domestic location for the show is pared-back; Rivrain’s flat-background depictions of (primarily) people and (occasionally) animals unassumingly populate an otherwise empty building. The sparse placement nonetheless takes over the space. Art hangs in corners, in front of windows, and at varying heights. As opposed to the traditional stark-white gallery, the bungalow mirrors the intimacy Rivrain captures in his work, inviting audiences to engage with the interiority of the paintings’ inhabitants as if visiting them in their own residences.

Being invited into someone’s home is intimate. Rivrain himself describes the work as “seductive.” Although most of the people he paints are in their underwear, Poussière articulates an important distinction between the seduction he refers to and sexuality. Enchanting raw materials (“poussière” translates to “dust” in English), Rivrain’s particular brand of seduction conjures his subjects, enticing them to present private versions of themselves to the world. Coming into unmediated contact with the viewer, each individual is unclothed and rendered in muted colors. Mundane moments—moving aside a bedroom curtain or taking off on a flight—are portrayed with care. “It was important for me to capture the essence of the people that I painted. The bareness of everything goes deeper into the person, entering into the subjects,” he explains.

To animate his subjects, architecture is necessary in each work. “Using domestic details like windows or doors creates this opening to a parallel dimension.” In accessing these parallel dimensions, memory and imagination become sources, rather than live models. These openings give Rivrain a chance to glimpse at the people he paints. “To recreate them I need their absence. That’s the only way for me to feel an urge to recreate their presence,” he says.

In Porte-Fenêtre, a stern portrait of two people closing a window, Rivrain calls upon the memories of his real-life friends, later replacing them with fictitious characters after he realized he was forcing a bond between them in his painting. “I felt that I created an artificial relationship with those two people. At the beginning of this painting, they didn’t even know each other. I knew them,” Rivrain admits. For this piece to function, he needs the two women to be authentic, instead of real.

Invented or not, one can’t help but look into the figures’ eyes and construct a narrative. A personality. A situation. The same is true when exchanging a glance in real life. On the train, at the post office, or across a street, shared moments rarely have larger narratives attached. Even when they do, human beings are still irreconcilably separate; they must recognize something of themselves in another to feel close to them.

“The subject looks at you in a painting… but I’m not sure they know who they are because they’re captured on a canvas,” he explains. “I’m not sure they know who they are looking at either.” Between these contextless strangers, relationships, however brief, are forged solely through this mutual staring.

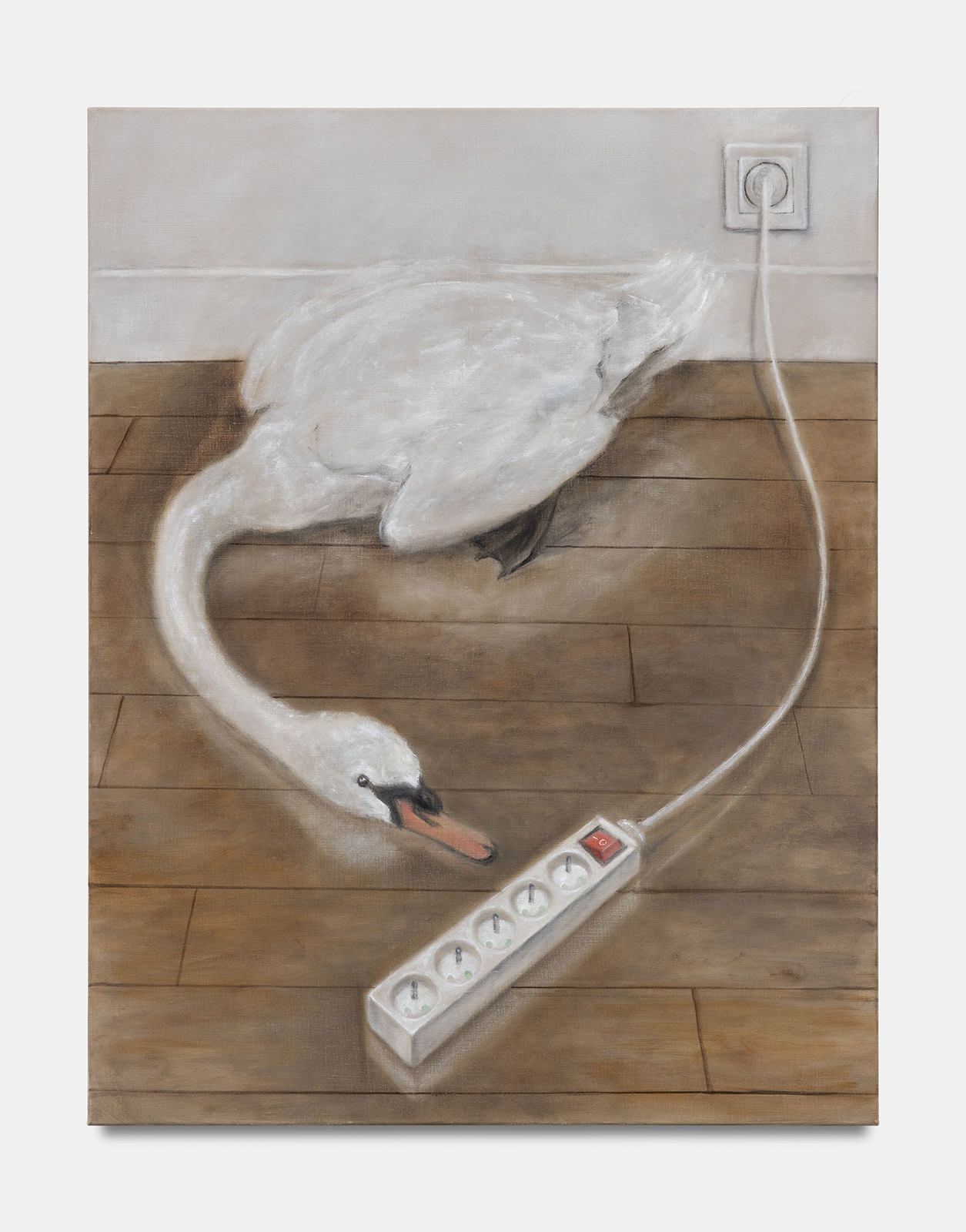

Rivrain’s paintings of animals—the ultimate other—test the limits of the kind of visual connection he cultivates. His non-human creatures are still relatable. Cygne et multiprise is a sympathetic work, despite the fact that most people have never been swans inspecting surge protectors. A mid-century modern home is no place for a swan—an analogous situation to the plight of queer people in a word hostile to difference. Cédric himself sees the swan as a gay character: “When I was a kid—I was at a lake in Switzerland with my parents—I saw swans really close for the first time. I was so fascinated by their over-the-top attitude. I do not know why, [but] I realized there was something gay in me. It was like a coming out in my head.”

Queerness—both in its pre-21st century and contemporary usage—exists at the core of his Poussière. It is queer to share moments like the unspoken ones in Rivrain’s paintings. It is queerer still to try and understand that presence, let alone immortalize it.