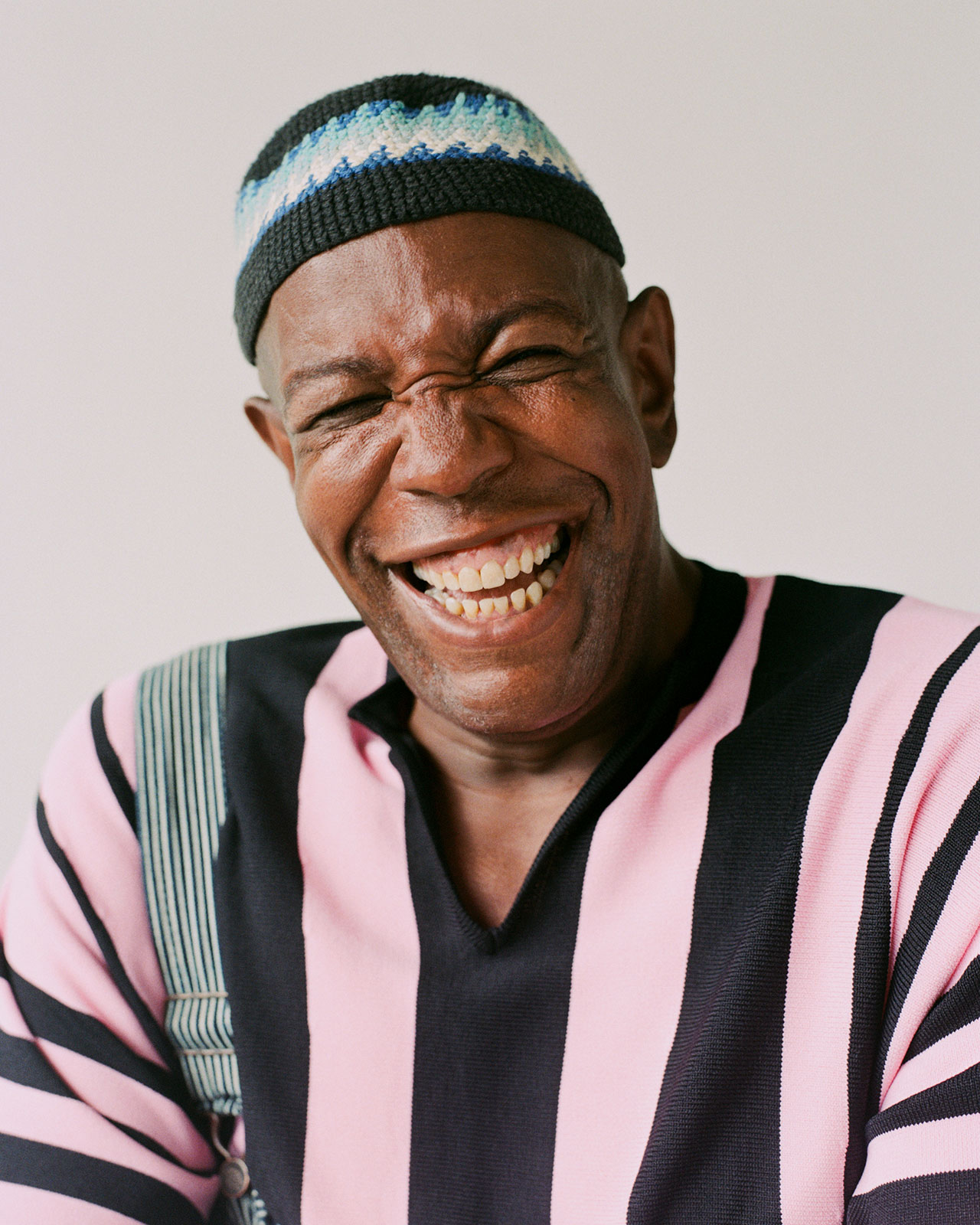

In her biweekly column for Document, McKenzie Wark passes the mic to Shawn Dickerson, to talk 40 years on the New York nightlife circuit

Vibe editor

By: Shawn Dickerson

I never went to Studio 54—for me that was aspirational. Looking at it in magazines, I’d imagine I’d go to New York and go there, but I was too young. I missed it by a few years. It was ’78, ’79 and I was still in high school, but I was fantasizing about it a lot.

I got to New York when I was about 21. I was in Florida for college, and I just felt ugh about it. I would come up here to see this kid from Florida who lived on the Upper West Side and worked at this club called Xenon. I would hang out with him while he’d be working, and I would talk to people to try to find where the gay people hung out. I went to Uncle Charlie’s. I started seeing the whole gay scene. I decided to leave Florida and come to New York.

That’s when I started going to Paradise Garage and Area. The thing about Garage, that whole experience, is that everybody was just hanging out together. It wasn’t about you being different to the other person. Like how I met Keith Haring: He was just smoking this joint outside, and this guy walked by, really cute, and we both came in looking for him. Keith smiled at me. We laughed and he asked if I wanted some of his joint. And then we would just kick it like that.

I guess I knew he was an artist, but he never really talked about that with me. I would see him hang out with certain people, but really everyone hung out with everyone, so you didn’t know who anybody really was unless they were really famous. He was on the cusp then. I remember going to this art opening; I walk in and he’s there. He catches me staring at him. He turns to me and we start laughing. Like the same way he always was. He was like, “oh, you didn’t know?” And I’m like, “No, queen.”

Keith was definitely part of the Garage scene. I had this moment of thinking that I wasn’t in the inner circle for a while, and I wondered if he was one of the people I wanted to get to know. I’d seen Grace Jones walk through, and I’m thinking what’s going on here? Then there’d be Madonna, with all the bracelets on (like in “Lucky Star,”) and I’d be like What’s going on? She’d just taken off. That’s how it was. Whoever was going to do whatever they did, they did it. But Keith was someone you could just get to know, and it’d be cool. He was one of the people I just wanted to hang out with. I remember taking a seat at Danceteria, and he’d come over to see me and my friends, warmly and honestly.

When I think back about the Paradise Garage moment, I guess that’s why people are interested in my story. I was around Basquiat and all those people, but I was so fucking young and just caught up living in that New York moment—being 22, and finding myself, playing with all this new stuff. Like we had these friends who were African royalty, they had diplomatic immunity, but they were drug addicts. All of a sudden limousines are coming to pick them up. I’m Hanging out with Marci Klein and she’s telling me stories about her father—Calvin. It was stuff like that all the time. I was so busy getting high. I was living.

I want people to know about those times and think about it. But honestly, I think the kids now are creating a moment like the one I saw. I feel it; I’ve lived through it enough. I’ve felt it happen a few times. And they’re just doing their shit and living their lives. That one is going out and getting fucked up or whatever, but they’re going to be the next William Burroughs.

I was at FIT [Fashion Institute of Technology] back then. I’d hang out getting dressed for hours. You’d have three or four looks before you. I’d be with my best friend at the time, Louis—he was the reason I’d come to New York. He decided he wanted to create this drag personality called Mercy Jones. He would be dressing up for hours, teasing his hair. He was Italian, really beautiful. We go out about 5.30 or six, and stay ‘til the end, which was usually about midnight. We’d hang out with the Xtravaganzas who’d all leave the club and go hang out by the Chelsea Piers—that’d be your Saturday and Sunday. The Xtravaganzas used to scare me a little bit.

When I was growing up in Philly my grandmother had this best friend George who was a transvestite and hung out with this really flamboyant friend, Tommy. The whole setting was that my grandmother ran a speakeasy. They’d all hang out at my grandmother’s speakeasy. Tommy would come over and get dressed up in her clothes and would tell stories and entertain. Tommy had lived in New York. Everyone’s just drinking and laughing. My grandmother loved it.

I was a kid, and George and Tommy would tease me until I’d be crying. I was always scared of anything too fast, or too flamboyant. I think I’m different now, but then it freaked me out. It was scary. They would tease the fuck out of me. I’d have a friend with me who was just a friend and they’d be like “Is that your boyfriend?” I’d be like, I’m not gay! They’d be like, “Queen…” I’d call my grandmother over to protect me. I kind of grew up with that.

In school, all my friends came out to me when we were in the ninth grade. I always thought that if someone is comfortable enough telling me their secret then who am I to judge? Who am I to refuse acceptance? It was always that way. Whatever it was, I’d be like, OK, that’s cool. My best friend Louis would take me to the park they called Judy Garland Park, that’s where they’d cruise. He’d take me there. He’d say, “Sit over there on the bench and watch out for the police.” I was always the lookout. It wasn’t until years later that I realized that I was putting myself in these situations because I was curious. At the time, it didn’t feel like my thing.

Maybe it’s a socio-economic thing. Like, my friend Lisa. She was really young when she started dressing up. She had a twin sister and started dressing like her sister. We lived in a tough neighborhood, but she’d be there in her outfits. I was being butch, while they were the ones fighting battles—I was not. All these things are lessons learned that have really served me in what I do now. I feel like they’ve given me access to this next generation that a lot of people that are my age don’t have. I’ve always accepted people as they are.

“There’s this whole door thing where I’m judging someone, and at the same time they’re judging me. I always think that’s interesting, they’ll look at me like, ‘What are you wearing, girl?’”

When I got to New York from Florida, the look was preppy. I was so into Polo, in matching colors. But then in my head, I was a fucking freak. I was encouraging Louis to do looks that I was never comfortable in myself, although as I got older, I got more and more comfortable. When I was at FIT, when we’d go out to the Garage, I’d first start dressing preppy like that, but Louis would be like, “Wear a skirt!” I worked in the knitwear lab, and I’d make these long skirts. I always liked what I called the Olive Oyl look, a really long skirt, a big puffer jacket. And then I started wearing wigs, with hats on top of them. I would just play around with that a lot.

It was interesting because when I was dressed like this, boys hit on me. Different types of people would try to talk to me, I would get different types of attention. I think all of that was also me experimenting with how people judge, and how they would judge me. But the reality is: that’s your bullshit, that’s your movie. I’m the same person right here. It’s all your projections.

Now I dress more like I used to when I dressed down. If I’m working three nights in a row, there’s usually one night I’ll not wear glasses, one where I wear glasses, or sometimes I wear fake glasses. If I wear black one night, I’ll wear color the next. I do love wearing skirts, and I do love the feeling at the door. When I put it on, it doesn’t feel like I’m trying to be feminine, it just feels like it takes away the power of this item. There’s this whole door thing where I’m judging someone, and at the same time they’re judging me. I always think that’s interesting, they’ll look at me like, “What are you wearing, girl?”

I started working door in the ’80s. I’d met my first boyfriend, Joe, and we lived in the East Village. Thursday nights we would always go to Boy Bar, which was on St. Marks. After a few months they asked me to work there. That’s where I started, probably about ’84. I was really young, in my early twenties. Then after Boy Bar, we’d walk down the Bowery to go to the Garage. It was seedy down there back then. I’d be getting into situations with homeless people along the way and Joe would be like, “Let’s just get to the club!”

We’d arrive, and Patricia Field would be sitting there. There was this connection between Patricia and Larry Levan, through this guy who worked for her, who like Larry was into dope. Larry was the star of the Garage. I started hanging out with him. There was this whole fashion connection. What’s interesting is that I think the same fashion-to-club connection is happening now. I see these young kids—I’m fascinated by them. They look like they’re deconstructed, or just falling apart, but then I look closer at the outfit and its labels, and I’m like, What are you doing? Girl, rent is expensive. I don’t know what you’re doing to afford to look like that! That’s what I love about the city. There’s so many stories.

I’ve worked door pretty much non-stop since Boy Bar days. I was doing that when Joe said: “Why not start a club?” He started Café Con Leche, and I worked it with him. That segued into Starlight Wonderbar—I put in about 10 years there. Then The Cock, everybody would hang out there. And then bigger clubs, like Twilo.

Joe would say, “You’re too small for the bigger clubs.” They wanted that thing that I don’t really do, the big tough thing, whereas for me, door is more psychological. I guess it’s like from the time I was with my grandmother’s speakeasy, because back then I would see the whole night. I’d see how, like this one is getting riled up. As I got a bit older my grandmother and I would have signals, like, Watch that one! I just got good at seeing people. Most people, when there is a situation, they just want to be heard. I’ve seen it so many times. The way they’re making it physical, it so didn’t need to be physical. So the bouncing thing is not really for me.

“The way Americans react to that “no” at the door, that’s such a different thing. In Germany people just walk away. They’ve been doing it such a long time. Here it’s like, ‘You’re going to do this to me?’”

In terms of today’s parties, when I work those T4T parties, it feels like there’s a real reason for me to be there. I can make someone feel comfortable in a way other people can’t. That’s my gift, my “superpower.” It feels very natural to me. And I think it’s important. In terms of clubs that are hard to get into, I was never really involved with those types of door. All that shady door stuff, like at Twilo or Sound Factory, was all performative. At the end of the day, that performance about keeping people out made people want to come to that club. It’s the same shit now.

At the underground techno parties that I work like Fluffer or Flanger we do try to keep out a certain kind of vibe. If people don’t get in, it’s usually based on entitlement. If you’re too much with us, then we’re going to get into it. Sometimes I work with Cedric, and I feel that his door is different. He’s very good at treating people well, but when he gets shady, it’s like a performance. We’ve talked about it. He’ll say, “I have an avatar. This is my avatar for the night.” Us working together at Fluffer, I learned some of that style.

Working Basement door has changed me a lot. There’s a speed of decision there. The security guys always laugh at it. Like I’ll say to someone, Oh I love your jacket, but the next thing that comes out of my mouth is Thank you so much for coming, but another time. The security guys are like, “You just smiled at that person’s jacket and turned them away, how do you do that?” I can do that because I know it’s not personal. I really liked that jacket.

It’s just really fast there. Those Basement nights, that’s thousands of people. I don’t know how many people I’ve interacted with at the door, a few hundred thousand, easy. I think in terms of how to manage people’s expectations. That came from watching my grandmother. I would watch her deal with problems—there was so much shade going on. She would have this whole signal system. And they’d put wider straws in some drinks, so people would drink them faster. If someone got too drunk and they were by themselves, you know someone would lift his wallet. It’d be crazy. That guy would be getting into it with my grandmother, and she’d be saying, “You accuse me of stealing?” When the whole time, she was the one with his wallet.

It’s funny, like every time I go to Berlin, I look at how the door feels. Basement always gets this whole comparison with Berlin, as if it were Berghain. But it’s never going to be. The way Americans react to that “no” at the door, that’s such a different thing. In Germany people just walk away. They’ve been doing it such a long time. Here it’s like, “You’re going to do this to me?”

I’ll say this: there’s certain nights particularly when I’ve had a really long shift, and I have to work the next night, when I’m just over it. Someone comes up, and I’ll try to be sweet, but I just want it over. I’m like, What do you need? Let’s get this over with, let’s get you in or get you out. How you do this depends on where you’re at. Do you have support there? That varies. Sometimes it’s like: “let’s just talk over here.” A lot of it is listening. The thing that’s really important is that anyone who’s in the perimeter of what’s going on, like smoking a cigarette or whatever, I want the situation to be as minimal as possible for them. The people around shouldn’t even know it’s happening.

The other day, Cedric and I had a situation at Flanger. You could see it was happening. Later I was told it was GHB. I didn’t even know this person did G, maybe he’d just been drinking. He was slurring and talking to himself. I thought: He looks like something is happening to him. You keep an eye on someone like that. He went back in, came back out; I was dealing with something else. Cedric was talking to him. I told Cedric I think you should walk him down a little bit. He’d be saying, “I’m gonna leave, I’m gonna leave,” and then he’d sit down and start to pray. He was in this loop, of getting up and talking, getting on his knees, praying. Sometimes we have to deal with things like that. You’re trying to get someone to go home. You’re just trying to get them to a safe place. It took a good hour with him. We were trying to get him hydrated the whole time with citrus and water. Finally he was able to get it together enough to go home. That’s the part I don’t want you to see.

“I had to ride the ride, and be on that show with her. Sometimes you’re not fully there, but they are; so they have you.”

It’s crazy on a Flounder night at [Redacted]. I would hate to be an EMT at that party. It’s the worst job ever. But a lot of places don’t want to be like the TSA at the airport. You know why people are there. With the GHB thing, it really is problematic because I just don’t see people controlling it. They’re not dosing properly or mixing it with other things. It’s hard when you’re in that state to say no.

I did this one party for Flocker—it’s a younger crowd. Those kids are really young. It’s quiet the first hour, there’s nobody there. This doll shows up, she’s zooted up, and she tells me this and that about her whole thing. But you know, I had to ride the ride, and be on that show with her. Sometimes you’re not fully there, but they are; so they have you.

Sometimes when I don’t have to be at the door, I like just walking through and dancing. Sometimes I’m checking to see how the vibe is. That’s part of the whole thing with working door. You have to see what it feels like. Does it need more of this or less of this? Sometimes I wish I could get in to dance sooner. I’ve had some DVS-1 evenings where—ah! I just want to get in there and get to it.

I love dancing to Carry Nation, but it’s a hard door to work. It’s challenging because a lot of regular Greenpoint people go to Good Room. Some of them are “bros,” and they’ll fight to get in. I can try to convince them not to want it. I don’t mind taking the straight dollar for the club, but sometimes they’re going to pay 30 dollars, and they’re going to stay less than 30 minutes.

Or sometimes the gay kids will be like, “There’s too many girls!” But there’s too many everything. One of the lines I really hate hearing from straight people on the door is “Well how bad is it?” Then I have to tell them It’s not for you. There’s nothing bad about this, it’s just not for you if you have to ask me that. Or they’ll ask, “Is it really, really gay?”

There was one guy—he was the cutest too, almost like a young JFK Jr.—who came up with two girls and a guy, like they were two couples. He asks, “Do you think I’d have fun?” I can’t tell you that. He’s asking, “Is it just too many guys?” I point to the girl he’s with and say, You probably won’t get hit on, then I point to him and say, You will definitely get hit on. Does that work for you? This is going to be part of the experience. I ended up telling him, It’s a little too gay even for me. And he says, “Right on!” We laughed about it.

Now that I’m taking acting lessons, I’m thinking about what acting is all about. You’re creating this exceptional thing that sometimes feels as unreal as possible, and making it a reality. That’s sometimes where you’re at with the club. There’s so many shenanigans, there’s so many levels. Sometimes you’re in space, sometimes people are including you in whatever is going on in their head. Particularly at Basement. There are videos from people we rejected on the internet. I try to tell everybody at the door to just try and come together for a moment, see where they’re at, see if they know the DJs. See if they’re part of the community, but just look different tonight. Some people are mad because they paid for an Uber to get there. That’s the entitlement thing.

I’ve been doing this for so long. I’m imagining myself not doing it. I’ll move myself out of it. After Starlight, I started trying other things, as I’d done that for ten years straight. Someone would ask, “Can you do this one party?” I did one party and then they wanted me for Fluffer. That was my transition from the house and gay world, to the techno underground thing. That led to Basement, Flanger, and now those Flocker kids want me to do a party with them in Berlin.

I think about how you document all this. My ex, he was obsessed with documenting the Garage. It goes back to my grandmother again. When I was a kid all she talked about was how Billie Holiday was so great in her day and I’d be like Will you shut up about Billie Holiday! I love Billie Holiday now. For me back then it was like Girl, okay, that was your moment, live. This is my moment. I’d be trying to tell her about the Garage, and she’d be like “Well, back in my day….”

I think about this a lot. You know the Pepper Labejia scene in Paris is Burning? Where she’s like, “I’ve had a good life.” I really feel that. The resignation of that. Particularly as you get older. Thinking about my uncle George and his best friend Tommy who used to tease me. They were getting sick. My grandmother was trying to be there for them. They were basically without family. I was so scared of that.

What was always important to me is that I had really good relationships with people. My chosen family became my real family. We were there for each other. But I get really inspired by the kids now. They’re just free in a way that’s kind of astonishing. Sometimes I’m shocked by it, but I’m just really happy for them. I just want people to be accepted. If I give anything to anybody, it’s that.