For the holiday season, tastemakers dispense a potent fantasy: the fleeting escapism of finding the perfect present

As a kid, my mom could never be caught buying another child a gift without also getting me (usually the same) one. I would throw tantrums: There was no affront quite like someone else getting a present that I didn’t. I’m her only child, why should anyone else matter? A few decades after these childhood foibles, my girlfriend told me about the presents she was giving our mutual friend for their birthday over pho, and my response was, naturally, Why are you getting them such nice presents, you could get me nice presents. My girlfriend, ever pragmatic, told me she was getting me nice presents. Fine, I sighed. Old habits die hard, I suppose.

Reading gift guides has been a pleasure of mine for years. I have always loved buying frivolous things, and there’s an intimacy in knowing what other people would choose to give. Gifting underscores desire, right? If not directly, then the act at least triangulates that desire: what the giver thinks the recipient wants, what the recipient actually wants, and how each party views their relationship via the item. And what could be more interesting than knowing what someone, especially a stranger, yearns for? If you like your recipient, you probably give something you think they’d genuinely want. If that person is similar to you, maybe you present them with something you would also want, but would rather gift than keep for yourself; like the time I finally ended up giving a Playboy ashtray I found on eBay to a friend, after they let me know that they really loved it.

“You may give a lavish holiday present, only to find that your recipient didn’t think of you at all. You may receive something you hate, that someone else thought was perfect for you. A gift is supposed to represent a nice gesture, and yet it’s fraught.”

In theory, giving gifts should be fun, easy, and exciting—a manifestation of thoughtfulness, by way of devoting your resources to someone else. And yet, the act lays bare so much else. In his seminal essay The Gift, French anthropologist Marcel Mauss writes that gift giving is “where obligation and liberty intermingle.” I liken this to the prominence of the phrase there’s no such thing as free lunch among men who have taken one econ class, and politicians who hate poor people. Mauss contends that gifting serves as a tool for much more than mere exchange: Social standing, sentimentality, morality, humiliation—all are at play, often simultaneously. You may give a lavish holiday present, only to find that your recipient didn’t think of you at all. You may receive something you hate, that someone else thought was perfect for you. A gift is supposed to represent a nice gesture, and yet it’s fraught. Should you be embarrassed for doing too much in the former scenario, or does it breed resentment? Should you be offended in the latter, say, when a relative seems to have thought you’d love an infinity symbol necklace from the clearance section of a chain jewelry store, or chalk it up to misunderstanding? And if it is a misunderstanding, does it mean something about your relationship, that perhaps they don’t really know you?

If you scroll through the many gift guides in publications, or on TikTok, you might feel excitement, jealousy, desire, and a sense of dread. Look at all the lovely things in the world! Look at all the potential, but look at that price tag! Is it too much? Is it good enough to prove my love? Maybe there are people out there who can decide on both what to buy and for whom without feeling like their relationship to the recipient hinges on their choice. But the average person can’t simply buy themselves or a loved one a $4,000 Loewe Squeeze bag to validate their devotion to the recipient, like Vogue’s tastemakers suggest.

“If there’s one thing the excessive guides can offer, it’s a fun (albeit fleeting) escape from the chaos, disaster, and dismay of the state of the economy, politics, and the tragedies we watch unfold in the world.”

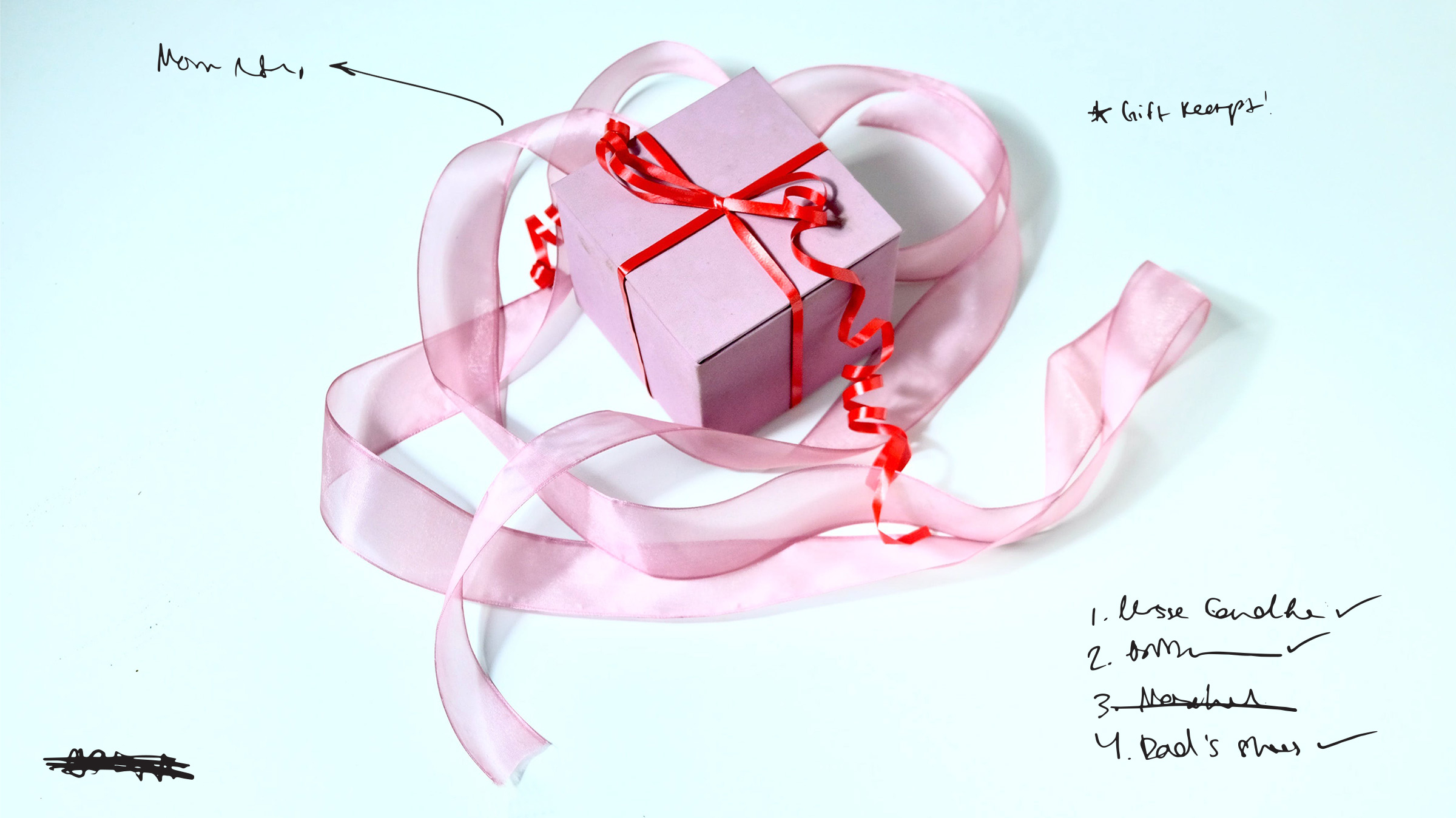

Given that the majority of Americans would describe the current economy as “chaotic, disastrous, and dismal,” it seems like even the $100 Loewe candle (which, thanks to this TikTok, did in fact make it onto my personal wish list) is out of reach. Despite this, it feels like aspirational gift guides have proliferated this year. Searching TikTok, for example, one can find guides for your favorite GirlTok archetypes; the “homebody,” the “cool girl,” the “bow & ribbon lover,” and “THAT girl.” These lists posit that, actually, everyone can be pinned to some amorphous aesthetic category; if you get it right, getting someone a gift that feels unique, despite coming from one of these ready-made lists, can make you feel like their coolest, closest friend. If there’s one thing the excessive guides can offer, it’s a fun (albeit fleeting) escape from the chaos, disaster, and dismay of the state of the economy, politics, and the tragedies we watch unfold in the world. It’s no wonder they have proliferated this holiday season, given what we’ve seen from attacks on individual bodily autonomy, to the large-scale destruction of entire cities. For a moment or two, I can inhabit a world of excitement, where my biggest worry is wondering what designer fragrance my loved ones may like best, and my biggest win is a positive reaction to whatever choice I make. I want to prove my closeness, my knowledge; and I’m sure I’ll be excited in turn, when it’s my time to receive. But then what?

Anthropologist Mary Douglas, writing the foreword for the English translation of Mauss’s The Gift, answers this question with a blunt statement: “a gift that does nothing to enhance solidarity is a contradiction.” Fancy things may not go beyond the act of pathological exchange, but perhaps (one can only hope?) the relationships and community we form with our recipients might.