The artist’s forthcoming album charts his evolution through relationships, looking inwards in the meantime

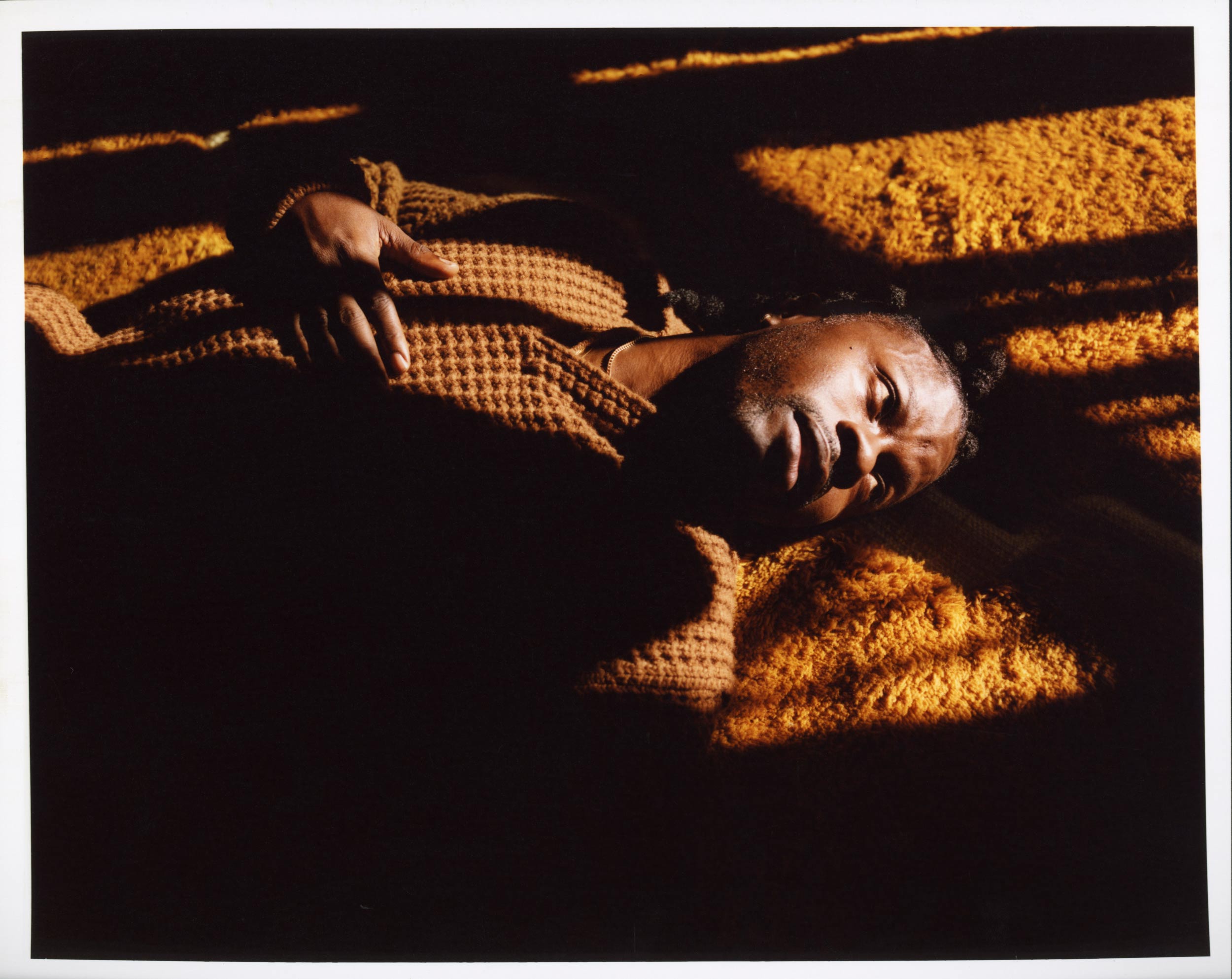

Of the many sleek, bassy tracks on his forthcoming album New Growth, musician Jesse Boykins III titles one song with a blunt directive: “No Pussy For Losers.” This single is one of those bangers whose hook is particularly infectious, partly because of its fluent translation from the vernacular of everyday life to lyric, but mainly for its straightforwardness. Alongside the more contemplative and deeply sentimental songs on the album, this track goes one step beyond, with Boykins issuing an unfettered assertion, to be chanted as a rule: “No pussy for losers, beggars can’t be choosers.”

New Growth is based on the idea that hard-edged masculinity is a point to mature from, rather than a staunch edict. Whereas the typical male crooner may simply flaunt his sexual adventures with women, Boykins can kiss and tell while looking inwards: On “No Love Without You,” he draws parallels between the nervousness his paramour inspires, and the act of taking a test; “Kind and Nasty” is one of those just wait for what I’m about to do to you songs, embodying both titular adjectives equally—Boykins wants his women kind, as much he wants them nasty, not as a conquest, but as an act of love.

As if produced with a finely-tuned lathe, New Growth articulates Boykins’s quest to reshape himself through tender sound—from the glittery synths of “Convo,” to the self-assured guitar twang of “Let It Come To You.” For Boykins, these realizations culminate in an understanding of the self, as necessitated by its ability to change over time.

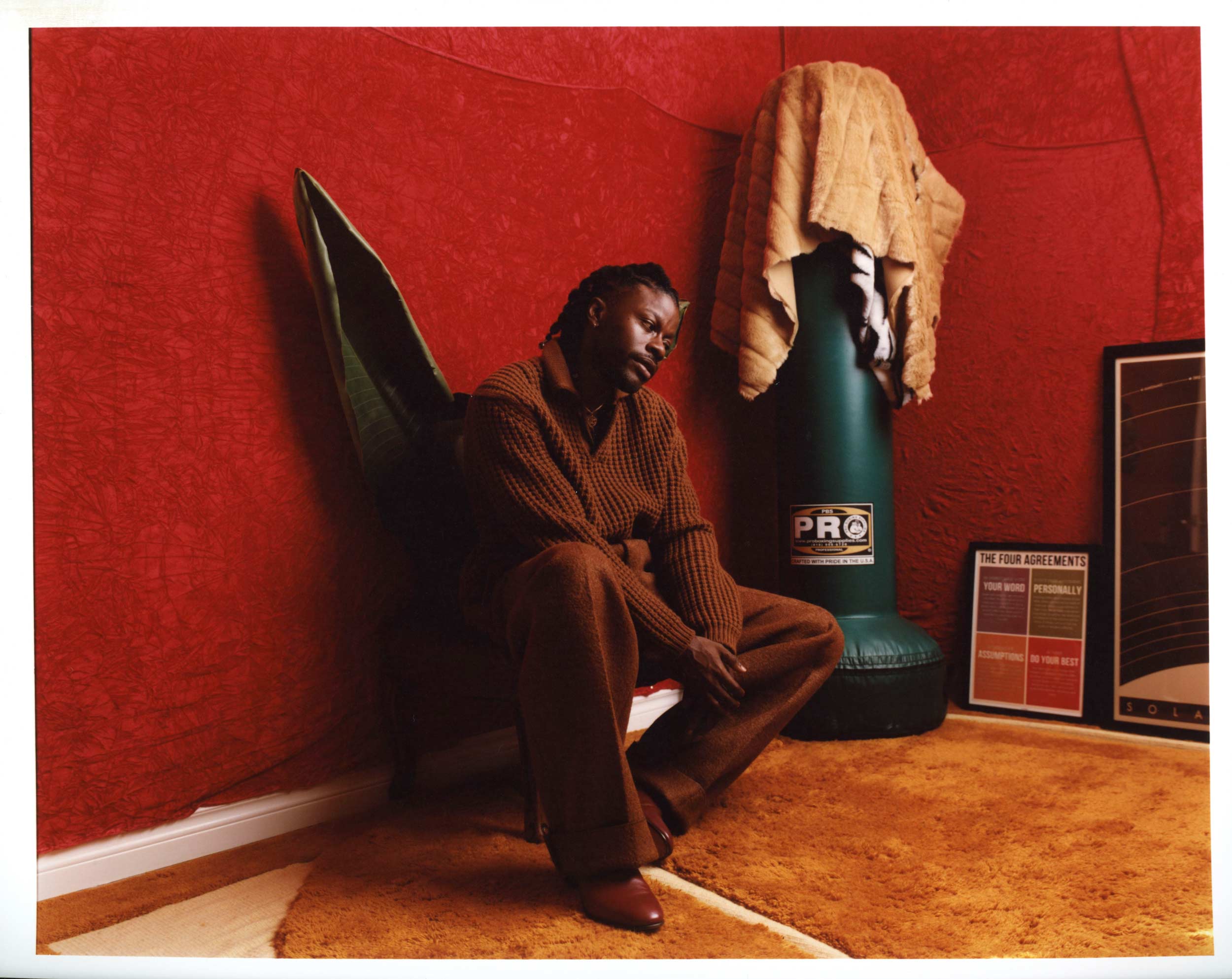

Maya Kotomori: Since you hit the scene, you’ve been known to have a very distinct swag. What would you say is your relationship to personal style?

Jesse Boykins III: My relationship with style is a history thing. I connect with a lot of different eras in a lot of different regions—for a second I was into Buddhism, so I was wearing all these pieces from India. I feel [my clothing] is distinct to what I’m learning or researching.

Maya: What’s a historical period that has been important to you, both in your style of dress and in your music?

Jesse: The ’70s, for sure—[specifically] Rasta culture. I’m Jamaican, so a lot of my references come from old photos of my uncles and my mom in the ’70s and ’80s. Seeing that they were so free in what they wore introduced mixing and matching and experimentation in what I wore. I think that aspect is also in my music, in the styles I choose to sing over and produce. I try to mix things that you wouldn’t think go together.

“I think about expressing something authentically—it might be a dark emotion, it might be light, it might be joyous, it might be fucked up. Artistry is authenticity, and musicianship is craft.”

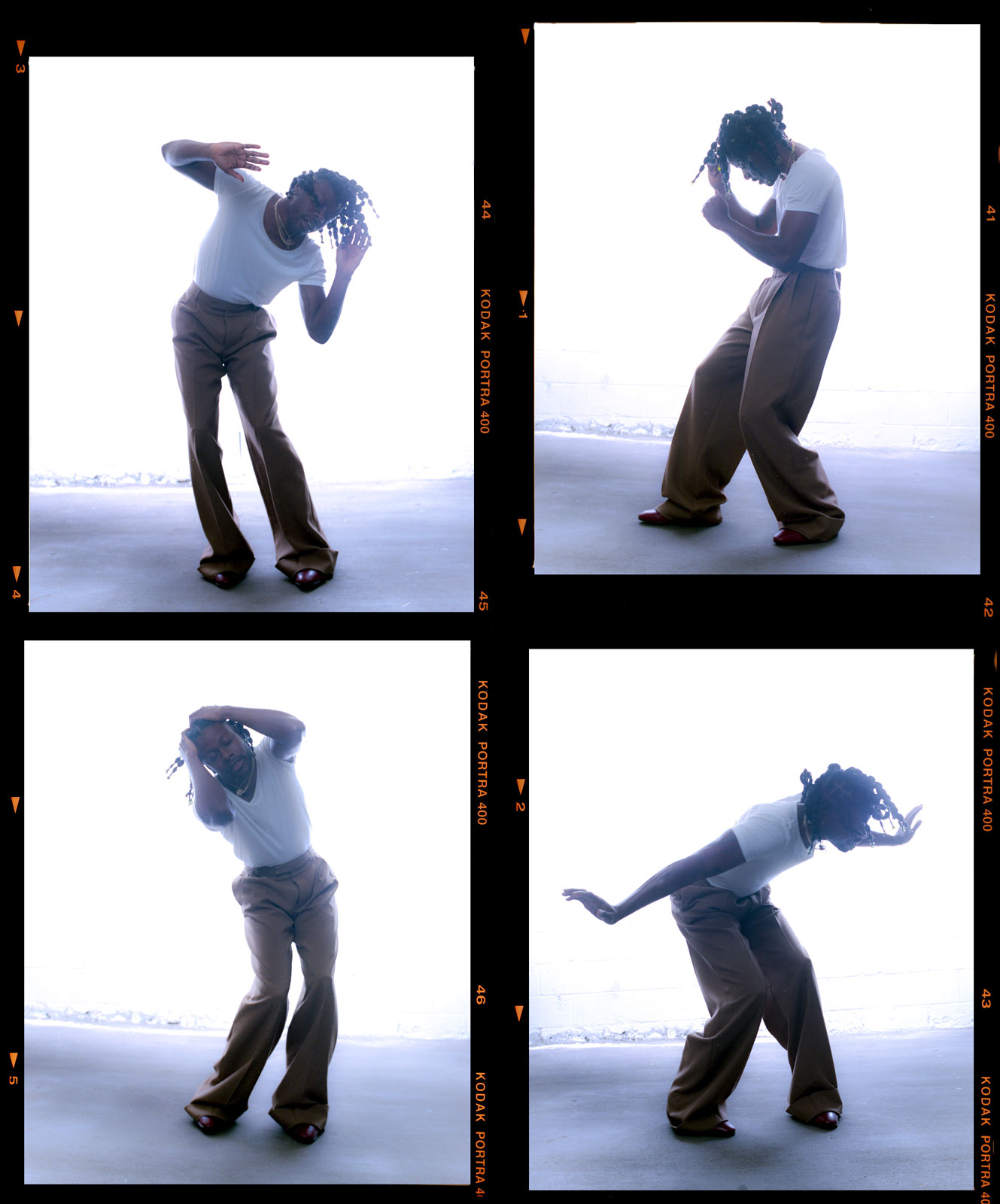

Maya: Where does that influence appear on New Growth?

Jesse: ‘Go With The Feeling.’ Funny enough, my mom came to visit me over the summer, and she got really excited when I played that song. I guess she forgot about it [though], because when I released the visualizer, she FaceTimed me in the car with a friend—they’re both from Jamaica—and was like, The new video wicked! There’s another song on my album called ‘Fun For Free,’ which is a blend of reggae and traditional Senegalese drums.

Maya: ‘Limit To Your Love’—one could argue that that song is a reggae song through and through. Do you aim to do more of those adaptations moving forward? How do you think they affect your process?

Jesse: Honoring things that influence you is an important part of the process. I like to celebrate what I’m a part of, not just what I do. Being able to give my interpretation of [a song] back to an audience is an important part of songwriting, [because] you are able to understand what songwriting does outside of your personal bubble.

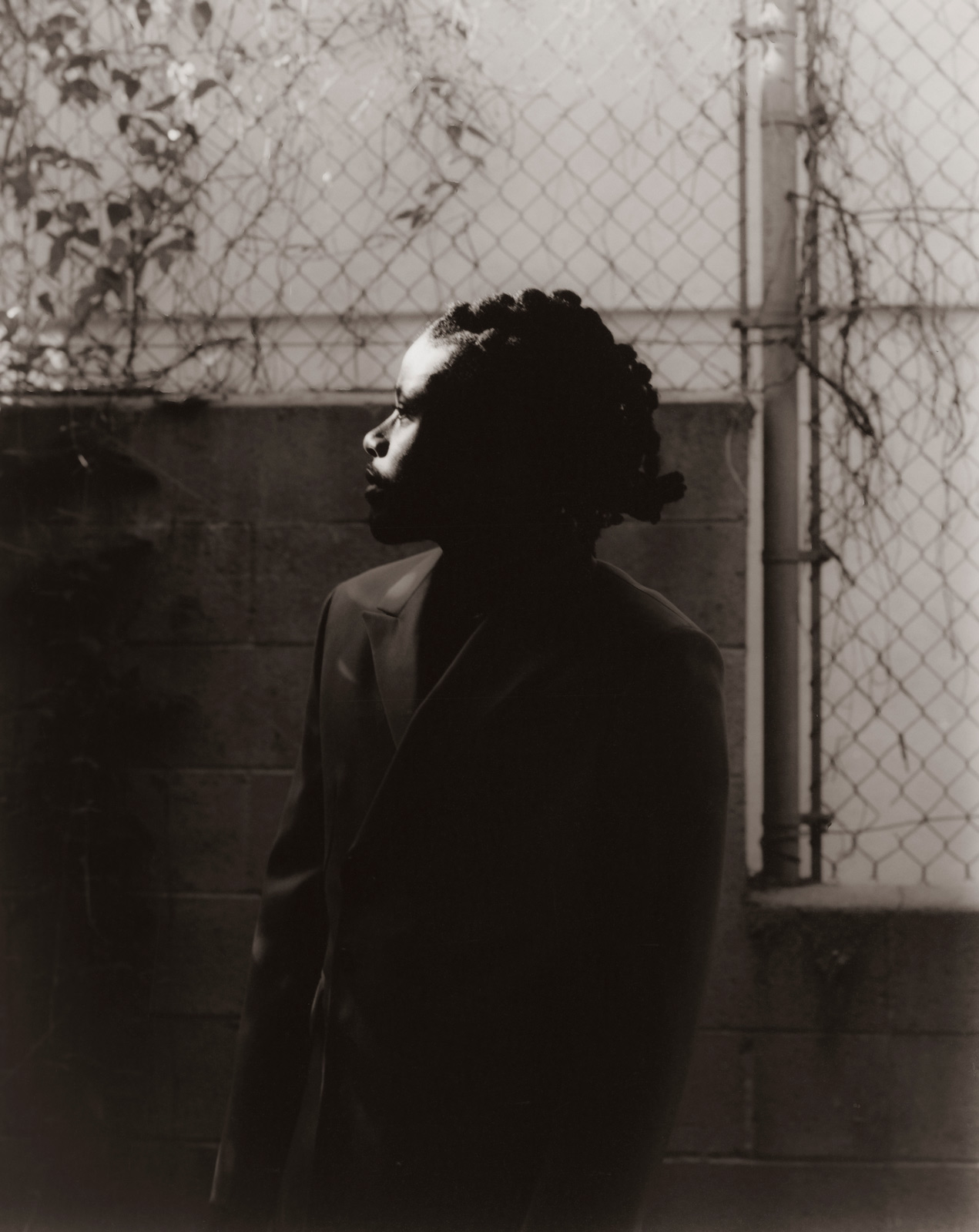

Maya: How would you describe yourself as an artist paying homage, and then how would you describe yourself as a musician? Are they the same?

Jesse: I think they’re separate. There’s this rebellious spirit in artistry; it’s about finding out what you stand for. When I think about artistry, I don’t think about just music. I think about expressing something authentically—it might be a dark emotion, it might be light, it might be joyous, it might be fucked up. Artistry is authenticity, and musicianship is craft. As a musician, I find myself wanting to create a space for my artistry to flourish.

For example, I was playing guitar at my studio one day with one of my homies. We [ended up] making t-shirts that say ‘No Pussy For Losers’ on the front, and ‘Because beggars can’t be choosers’ on the back. I’m just bullshitting [on the guitar], and then I start singing, ‘No pussy for losers.’ I was like, Well, if I continue to sing the song, it has to sound this simple and beautiful for me to be able to say what I want to say. [The shirt] and the song interact, and I appreciate the push and pull of these two things: artistry and musicianship.

Maya: I have to ask about that song—it is an earworm. Apart from that time in the studio, how did it develop?

Jesse: The song is actually me talking to my younger self. I think we live life based on potential—and I don’t like that. I don’t want somebody to be like, I see so many good things in you, so I’m gonna give you this before you actually earn it. When I was younger, I was getting acknowledged for what I was doing, and I was taken advantage of. I wasn’t necessarily understanding that everything I thought I was getting, I should have [already had]. I’ve learned that we all are motivated by a lot of darkness; not saying that love or intimacy is [exclusively] that, but sometimes it can be weaponized, and most men will accept what they don’t deserve.

Maya: What has your musical journey been like thus far? How did you get your start?

Jesse: In the beginning, I just wanted to be on-stage, and I really wanted to go to college; that [had] more priority for me than signing a piece of paper that I didn’t really understand. When I went to college, I [started] singing background for Lyfe Jennings, Keyshia Cole. I would always quit or just stop showing up, because I didn’t like the dynamic or I wanted to sing my own songs. I just wrote, taught myself how to record and produce—I would record my friends at my school [for their projects]. I didn’t have any mentors in that space, so I was really green. And then I graduated, had to eat, so I got, like, four jobs. I was outside selling CDs on Broadway.

I did a deal at Def Jam, and then the cats who signed me left, and I got all these things I was promised: the budgets, the creative directors, the stylists for music videos. My video for ‘Earth Girls’ was the first video that I had people come in and work on, and I asked to leave the label right after.

Having to fight for someone to communicate the fine print of my contracts was my biggest issue. That’s when I started collaborating, writing, and producing with [people like] Steve Lacy, Syd, and Charlie Puth. Then I met my publisher, Tim Blacksmith, who signed Sam Smith and Charlie XCX. He’s Jamaican, I’m Jamaican. I feel like he understands what I’m after, and what spaces I want to create. I’m very big on developing some sort of safe haven for artists to be themselves, and to provide for themselves.

Maya: Do you think the music industry has changed in a way that matters for an independent artist?

Jesse: Yes and no. I think CDs were a certain type of business structure for a long time, and then streaming came and artists became really successful, because it was a little ahead of its time. The labels were freaking out, and positioned themselves as the middleman—they did those deals with Spotify and Apple. [Musicians] don’t have a union, so it’s easy for them to do that. I think the music industry is still the same in a way where you’ve got the top five percent: Rihanna, Drake, The Weeknd. Then you got some shit in the middle. Then you got, like, me at the bottom, coming up to the middle, and I’m like, Okay, it’s nice up here! And [the structure] is like, ‘You know too much, stay down there.’

I look at myself as a curator. If I think of an idea, or I meet somebody who I feel [would work well] with another artist, I call whoever and bring this artist to them. I go between wanting to be this executive person who helps people connect, and being an artist.

Maya: Where did the concept for New Growth come from? What do you think audiences need to know before they give it a listen?

Jesse: I’m gonna give you a call to action. When I listened back to my album, I thought about how many Black men have a hard time expressing their feminine side without feeling like they’re losing the masculine aspect. This album is about me celebrating both, and all the emotions that come and go with that.

I curated the songs based on this script I wrote [specifically] for the project—it’s like a sci-fi rom-com, and it’s a series of questions.One of the questions the main character asks is, ‘When God created Adam and Eve, do you think Eve was really fucking with Adam, forreal?’ And this woman goes, ‘Well, if you think about the quality of men right now, Eve was probably asking for more.’ His rebuttal to that is, ‘That’s clear. But if I’m the first man on the planet, and I have to be with the first woman ever, I’m gonna need some guidance.’ What a lot of the album is about, is me wanting to understand the feminine, [while also] trying to unlearn these aspects of the masculine I don’t [need].

Groomer Jessica Harris.