In elegiac, lyrical, wry, snarky, and wonderfully plain-spoken prose, the author crafts characters through conversational pairs

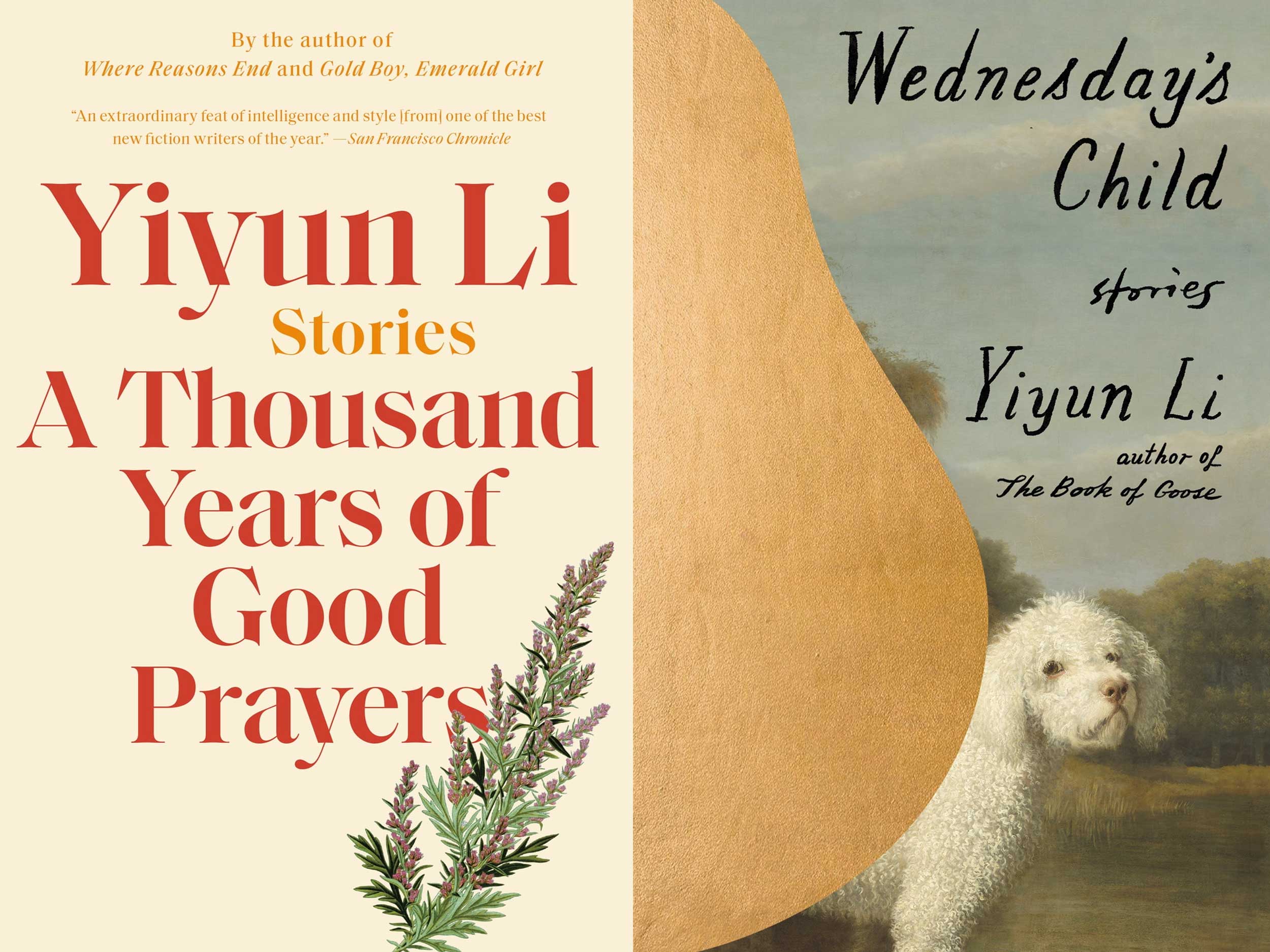

In sociology, the term “dyad” refers to a significant relational pair. Husband and wife. Brother and sister. Parent and child. Across Yiyun Li’s prolific career—10 novels, two story collections, and a memoir, as well as several works of criticism—this structure surfaces again and again. The stories in her most recent collection Wednesday’s Child teem with pairs: a mother and her deceased daughter (“Wednesday’s Child”), an elderly nanny and her client (“A Sheltered Woman”), a pair of friends (“Hello, Goodbye”), a woman and her former teacher (“A Small Flame”), an octogenarian former etymologist and her middle-aged caretaker (“Such Common Life”). In Li’s work, the dyad often becomes the locus or node around which a story whirls.

Perhaps the most common set up for a Yiyun Li story: Two people—whose relationship’s contours have yet to be defined—speak to each other. Her novels often play out in the form of extended conversations, with interludes of action and reflection. There is frequently an element of philosophical debate, where characters—with varying degrees of candor, irony, and humor—pose fundamental, often existential questions about how one should live, given the certainty of continual suffering. But if any of this implies to the unfamiliar reader that Li’s writing is academic, professorial, or didactic, rest assured it’s the complete opposite.

Across her books, Li’s writing is versatile and protean. Her prose can be elegiac, lyrical, wry, snarky, and wonderfully plain-spoken. If characters are dispensing hard-won pearls of wisdom, the writer is generous—if sternly attentive—to the psychological faults and deficiencies in their interior logics. To paraphrase Emily Dickinson, Li’s characters tell the truth but they tell it slanted. She never quite lets anyone off the hook, including herself, as in Where Reasons End; its narrator, Li’s fictive stand-in, is often described as “gormless” and is chastised by her son for being imprecise, lazy, or—that cardinal sin—cliché in her use of language. If a character says something that smacks of certitude or “wisdom,” we sense Li behind us, gently prodding a closer look, to scrutinize, to re-examine.

Li’s most frequent dyad is that of the storyteller and the listener. Her protagonists often find themselves drawn to characters—despite their various foibles and flaws—for their captivating ability to tell tales, to turn the most minor of life’s dramas into narrative. In Wednesday’s Child, Li writes: “Nina liked to be told stories, and Katie was good at telling stories.” And then again, in The Book of Goose: “I never made up stories, but I was good at listening to Fabienne.”

Often, Li’s ostensible “plots” seem to be a pretext for the real meat of the story: that same ongoing dialogue. At the center of The Book of Goose, her most recent novel, is the dynamic, complex friendship between Fabienne and Agnès. The major events that unfold in Agnès external life—her ascension to literary celebrity, her departure from her rural home to attend boarding school, her isolation, and her eventual expulsion—feel, at times, like incidental episodes. It is easy to imagine another writer mining these same plot beats for their full, melodramatic potential, producing a pulpier, less interesting novel in turn. Li chooses the riskier route. She lets the continual conversation between Fabienne and Agnès occupy center stage.

“Across her work, Li seems particularly fascinated with the kind of shaping—of oneself, of the future, of the past, of others—that happens when two characters speak, in agreement or in argument.”

One essential feature of the dyad is its dynamic of attraction and repulsion, compellingly fueling many of the relationships depicted in Li’s work. We see it in Agnès’s all-consuming dedication to her friend Fabienne, against the external forces that are determined to pull them apart. When the dyad encounters a third person, it must adapt in order to endure.

“How do you grow happiness?” Fabienne asks at the beginning of the novel. The girls are 13, but they feel that they are older. Growing up in impoverished, postwar rural France, their lives are far from idyllic. Already, they have experienced more than their fair share of toil, drudgery, and death. But the two have also managed to carve out a shared, private world, an Eden of sorts, sustained through language.

Of course, it cannot last forever, and their fall is inevitable. When the two girls hatch a plan to begin to co-write books, outside forces enter their world. First, their “mentor” M. Devaux, the neighborhood postman harboring failed writerly aspirations, who capitalizes on the potential he sees in them, eventually resulting in scandal. And later, much more potently, in the form of Mrs. Townsend, the headmistress of the English boarding school Agnès attends, as she attempts to undermine her epistolary correspondences with Fabienne. The novel can be read, ultimately, as a story of the evolution and eventual dissolution of this fraught pair.

In Where Reasons End, Li’s 2017 semi-autobiographical novel (although neither of these terms really do the book justice), the dyad goes from an essential plot mechanism to become the plot itself. Put another way, the structure becomes superstructure. Very little actually happens. The entire plot could be summed up by a single sentence: A woman and her dead son talk to each other.

Where Reasons End takes a question—what would it be like if we could speak to those who have died?—and lets it play out in the form of a book-length conversation. The narrator, a mother (also a writer and a kind of sly stand-in for Li) addresses her son, Nikolai, who died by suicide and now speaks to her from beyond the grave. Their conversation is a unique, meandering thread, chatty and cutting in turn, somber and joyful, existential and quotidian, without an apparent destination or clear purpose. Their discussions drift from etymology, to music, to baking, to Wallace Stevens’s poetry, to time, emptiness, to grief.

“The conversations we witness between Li’s dyads mimic a similar linking and unlinking—a repeated thesis, antithesis, synthesis.”

In Where Reasons End, stripped down to its barest essentials—with setting and character reduced to the nearly incidental—we can see clearly how the dyad functions as a narrative container. The novel poses the implicit question: In the absence of a conventional plot, what is left? What breathes life into these characters? The answer, at least according to Li: conversation.

As with Agnès and Fabienne in The Book of Goose, and many of the pairs in Wednesday’s Child, the format of the dialogue between Nikolai and his mother provides a stage upon which Li makes her characters’ thinking legible. They unveil their pasts, lie, write and rewrite their personal histories; they display faulty logics, glaring omissions, self-deceits. Across her work, Li seems particularly fascinated with the kind of shaping—of oneself, of the future, of the past, of others—that happens when two characters speak, in agreement or in argument.

Where Reasons End recalls foundational texts in the history of Western and Eastern literature and philosophy: the Analects of Confucius, Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy, and the dialogues of Plato. Like Plato, Li uses dialogue as a vehicle for the development of characters’ thoughts, a staging ground for ideas, a platform upon which beliefs can be argued and defended. Like Socrates, Nikolai is inquisitive, challenging, skeptical. Written while Boethius was imprisoned by the Gothic Emperor, The Consolation of Philosophy—like Where Reasons End—is narrated from a position of isolation and despair. In both, their narrators find comfort and companionship with a ghostly interlocutor who appears to them all of a sudden, miraculously.

For Li, though, unlike Confucius or Plato, the aim isn’t as clear cut as a pursuit of knowledge. The dialogues are not a simple means to an end. Nikolai teases his mother for sounding like “a mediocre self-help book.” There are no easy solutions given here, in the end, but the talking was worthwhile.

At the very end of Where Reasons End, the narrator tells us: “For days and weeks after Nikolai’s death, I had spent much of my time in his room, knitting, unraveling, knitting, unraveling.” Like Penelope in the Odyssey, weaving and unweaving each night, awaiting her husband’s return. The conversations we witness between Li’s dyads mimic a similar linking and unlinking—a repeated thesis, antithesis, synthesis. As characters speak, consensus forms and is broken; ideas are rebuffed, solidified, re-wrought. Each story, each pair, each conversation, a link in a daisy chain, continuing ad infinitum.