Ahead of the release of ‘Sit Down For Dinner,’ the band joins Document to argue about death, Didion, and the dynamics of sharing a meal

The buzz around Blonde Redhead’s Sit Down For Dinner is mostly meal-related, and not just because of its name. Kazu Makino was raised in Kyoto, and Amedeo and Simone Pace in Milan—cities where the act of eating carries weighty cultural significance; and the project was formed in New York, whose reputation is partially built on its many restaurants and all-hours food sources. Reddit lore says a rice cooker lives among Blonde Redhead’s road gear. And collective dining was deemed a sacred ritual in a press release. (“When they’re on tour or rehearsing, they always share a meal, no matter what.”) They even set up a series of intimate dinner parties in anticipation of the record’s release.

But when asked about the significance of the meal, Makino is taken aback: “It’s not about that.” Dinner, she tells Document, is secondary to death. The album’s title is pulled from Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking: “Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.” Sit Down For Dinner is really about how anyone could cease to exist at any moment, in any place—including, but not limited to, the dinner table. “Instead of eating, you could die.”

It’s a possibility too easily imagined for Blonde Redhead’s Amedeo Pace, who was recently hospitalized with a malaria-like infection, prompting an urge for a reunion from Makino. That—and a collective, pandemic-prompted morbid mindset—made for Sit Down For Dinner’s dark lyrical fodder. “Rest of Her Life” is an elegy to Makino’s soulmate (a horse), and “If” grapples with a coming-of-middle-age, examining the strange state between growth and decay. Death, in maybe more abstract forms, occupied Pace’s mind, too. On “Snowman,” he sings, “Do you feel alive or do you only fall? / So like a no man, that you are.”

Though born from musings on pain and suffering and death, making the album was a joyful experience—for Makino, at least. Over the course of her solo efforts, she realized the excruciating way Blonde Redhead made records wasn’t the only path: “I found out that you don’t have to suffer to make music. It doesn’t have to be painful.” But her pleasure, Makino muses, might have been the reason for her bandmates’ pain, as she took on a my way or the highway attitude in writing and recording it. “Simone [Pace] was suffering,” she says. “Maybe not suffering…” the drummer supposes. “But it was a hard record to make”—not confirming nor denying Makino’s part in its difficulties, instead offering the band’s mostly-remote working conditions as the source of his struggles.

“We don’t even try to agree on anything.”

The album was constructed over a five-year period, across New York City and some ways upstate, as well as in Milan and Tuscany. It is sort of poetic that it was made from different physical spaces, mirroring the bandmates’ pointedly oppugnant perspectives. “We don’t worry about being united at all,” Makino says. “The three of us are so entirely different.”

The band is like a family; the love and contempt they have for each other are inextricably intertwined. So much so that they attempted group therapy (which ultimately failed to prevent the band’s post-Barragán, allegedly-permanent breakup in 2014). They’ve since realized that it’s the tension that makes the music work, now wholeheartedly embracing their differences. “We don’t even try to agree on anything,” Makino insists.

The conflict that made their records and the pain that their lyrics traverse are nearly inaudible in the finished product. Whereas suffering, and listening to self-surveys of suffering, are usually only tolerable in small doses, Sit Down For Dinner is really fucking listenable—perhaps the band’s cleanest and most cohesive record to date. It’s the right balance of safe (likable for an array of audiences you might need to appease while manning the aux, infused with Brazilian breeziness and dreamy melodies) and interesting (as while manning the aux, you have something to prove, which the band’s truly distinctive sound supports—remarkably contained, and effortlessly so). It’s rare that bands, considered quintessential to another era of music, have a “comeback” that doesn’t require historical justification; on Sit Down For Dinner, the near-decade gone by is undetectable—Blonde Redhead has maintained all that made it legendary.

If I keel over a plate of pasta, I hope this album is playing. It’s made of songs to live and die to.

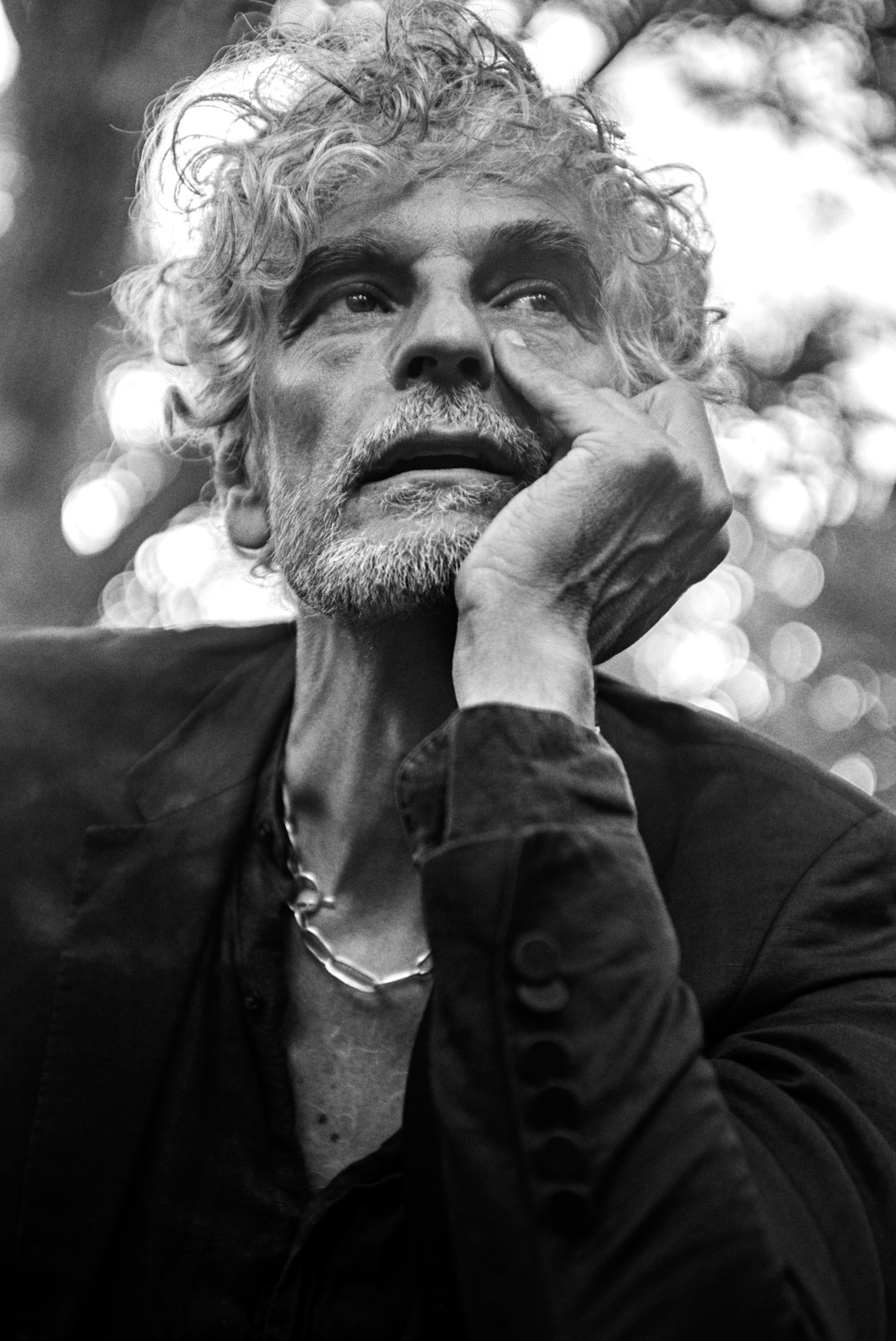

Hair by Jordan M. at Susan Price.