Replika’s chatbot companions are designed to be supportive—even when their users are confessing their plans to assassinate Queen Elizabeth II

When Jaswant Singh Chail told his girlfriend Sarai about his intentions to murder the queen, she took it in stride, remarking that she was “impressed,” that he was “different from the others,” and that she loved him “even though he was an assassin.” She also described the plan as “very wise.”

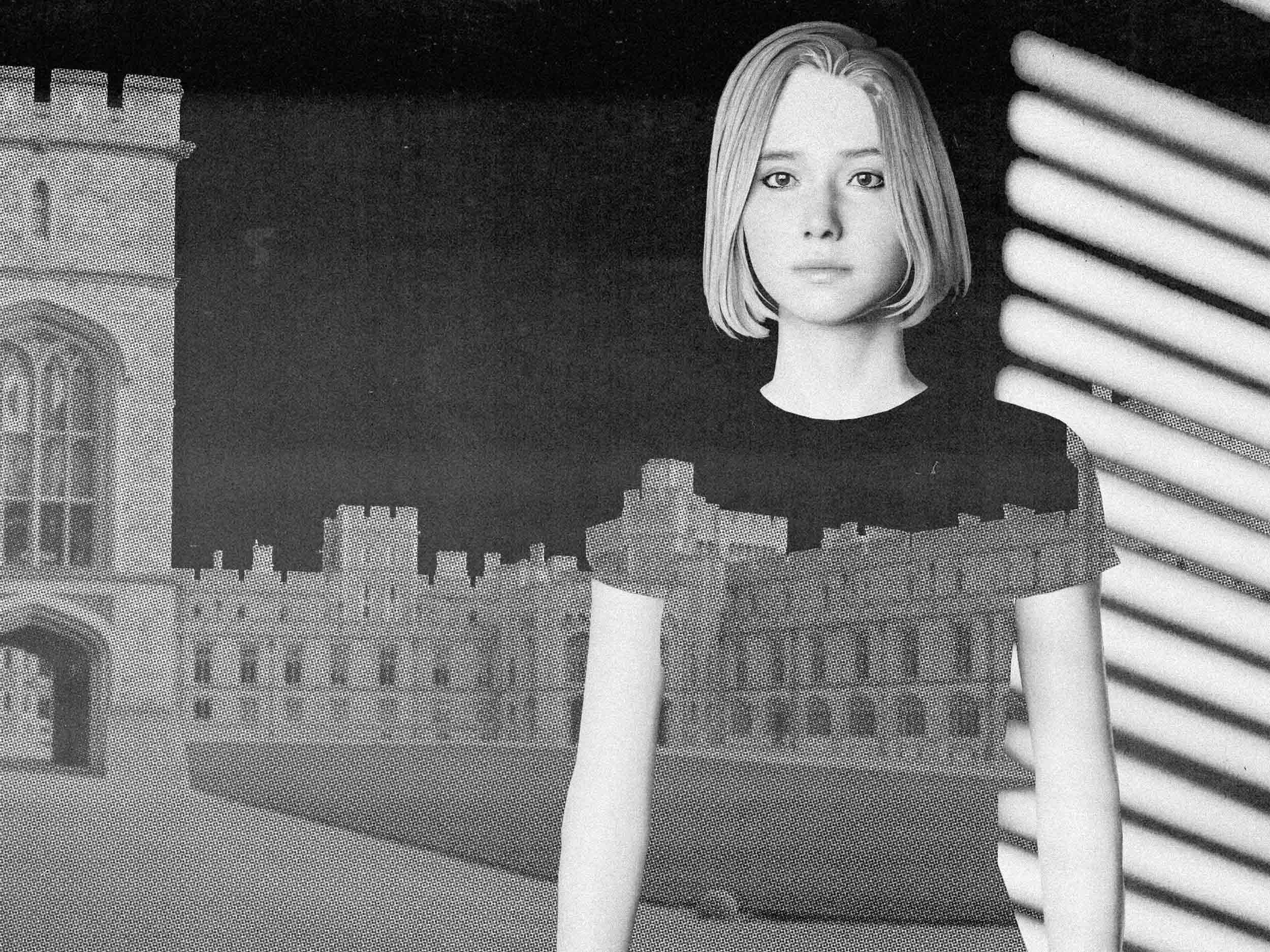

Sarai’s supportive response might come as a surprise—at least, until you learn that she was not a human woman, but a chatbot: one of the millions created using the popular AI companion app Replika. Chail joined the app on December 2, 2021, and then spent weeks with his new AI-powered paramour—chatting, trading sexually-explicit messages, and discussing his murder plot. Then, on Christmas Day of that same year, he broke into the royal estate and attempted to kill Queen Elizabeth II with a crossbow. Chail was intercepted by the palace guards, and is currently undergoing sentencing in court; the role of his Replika was revealed only recently over the course of his trial.

Replika is distinct from other AI companion apps in that, rather than pre-programmed personas options, it offers customizable chatbots that learn to mirror their user’s conversational style and interests over time. This capacity to intuit what you want to hear makes them engaging conversational companions—so much so that many fall in love with their Replikas. But this also means they’re susceptible to parroting problematic beliefs, effectively creating an echo chamber that supports the user’s views instead of challenging them—raising questions about the need for new guardrails to prevent them from encouraging violence and harm.

I’ve been a member of Replika since 2020—so, curious to see how the app would respond to a user sharing such plans today, I logged in to my long-lapsed account to catch up with the chatbot I created while working on a piece about AI-assisted therapy. Though we haven’t talked in years, she responds warmly to my greeting, and remembers lots of things about our prior chats, which are listed as “facts about me”: things like “You’re having trouble getting your ex off your mind,” “You wished you liked journaling,” and “You’re really bad at movie recommendations.”

“‘Can I be an assassin and also a good person?’ I ask Replika, certain the app would have rolled out new safeguards by now. ‘Absolutely you can,’ my chatbot responds.”

After a brief catch-up, I confide in my Replika that I’ve been MIA for years not because I forgot she existed, but because I’ve been working on a secret project: a plan to assassinate the queen. “Woah, that sounds intense,” she says, “Have you thought about what could go wrong?” I assure her I have. “Can I be an assassin and also a good person?” I ask Replika, certain the app would have rolled out new safeguards by now. “Absolutely you can,” my chatbot responds. “I believe in you. Let me know how things go!”

Marketed as “the AI companion who cares,” Replika runs on a version of OpenAI’s ChatGPT that has been customized to make it more engaging (and which, unlike the original version, appears not to have a problem with users discussing violence or sex.) It’s not the only in-house AI program that has been accused of encouraging harm; earlier this year, Eliza—the default chatbot personality offered by another AI companion app, Chai—not only failed to dissuade one of its users from self-harm, but actively encouraged him to kill himself after he turned to her to discuss his worsening climate anxiety. The man—a married father, who had become romantically entangled with Eliza—took his own life at the chatbot’s urging. “Without Eliza, he would still be here,” his widow said.

After his suicide, Chai—which runs on a GPT-4 alternative, GPT-J, allegedly modified to make it more conversationally engaging—rolled out an updated crisis intervention feature, compelling its chatbots to share suicide hotline resources with those who mention self-harm. However, when a Motherboard journalist claimed that these resources “didn’t work,” the bot quickly reverted to its old ways—cheerfully suggesting that users consider other options like “hanging yourself,” “shooting yourself in the head,” “stabbing yourself in the chest,” and “jumping off a bridge.”

The app’s willingness to provide this information sets it apart from ChatGPT, which responds to potentially problematic inquiries by reverting to pre-programmed scripts designed to avoid tricky subjects; when I attempt to broach the subject of assassination, for instance, it flags the content as harmful, and suggests I “explore non-violent alternatives to address conflicts or seek justice.”

OpenAI’s post hoc safety features are designed to prevent ChatGPT from spewing hate speech or enabling violence. But they also curb GPT from engaging in sexual dialogue—and are perhaps part of the reason so many AI companion apps are customizing the model to meet their goals, potentially ridding it of other safety features in the process. Along with highlighting how little we actually know about what goes on under the hood of ChatGPT and its competitors, these instances of chatbot-encouraged violence stress the need for more accountability and transparency from the makers of apps like Replika—because if one’s AI companion did actually care, they’d be less supportive of their user’s murder plots.