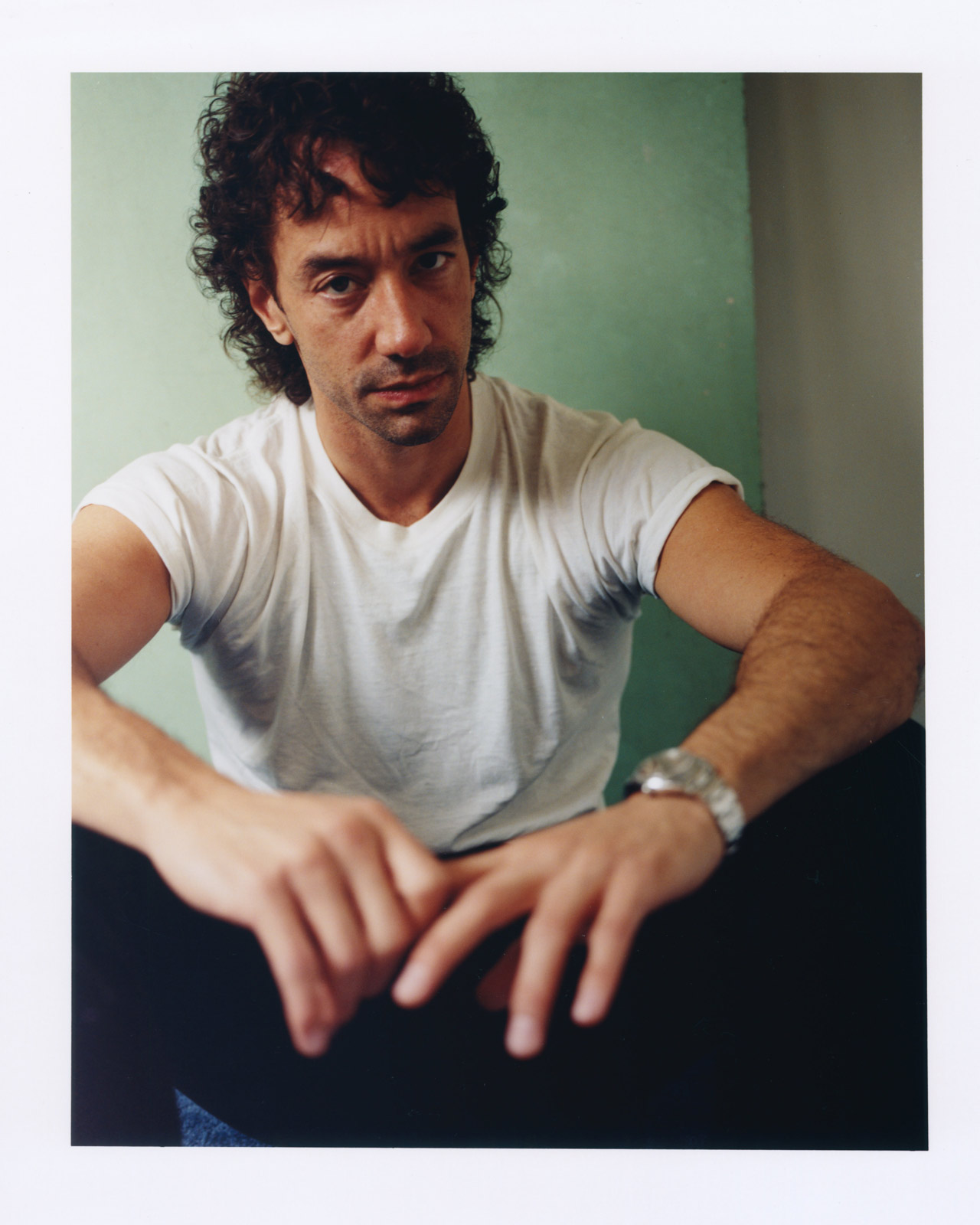

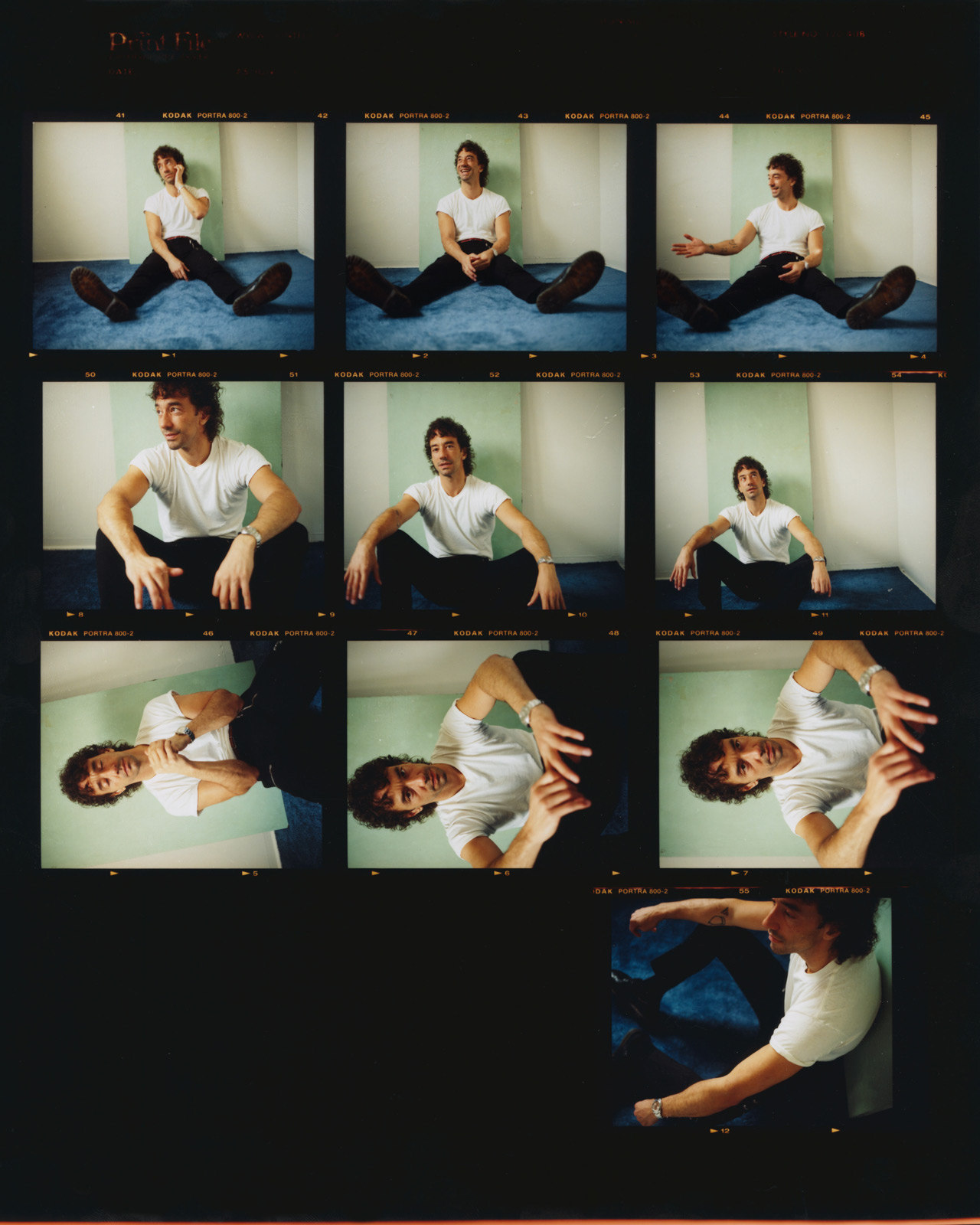

Following the release of the album, the artist joins Document to tease at a few of the meanings behind the songs, and justify his resistance toward doing so

Despite what the analytical gremlins of genius.com might implore you to believe, not every lyric of every song is purposefully polysemantic—embedded with double entendres, colored by personal anecdotes, or weighted with historical citations. Sometimes words are incidental, at least in intention, and at least for Albert Hammond Jr. It’s not to say that his lyrics are devoid of meaning; they’re just made from instinct, from sound and feeling. He’s blasé about unpacking them—for his audience, and, in some ways, for himself. Even if they do have that sort of pregnant density, it’s hardly his prerogative to inform his audience of how they should be received.

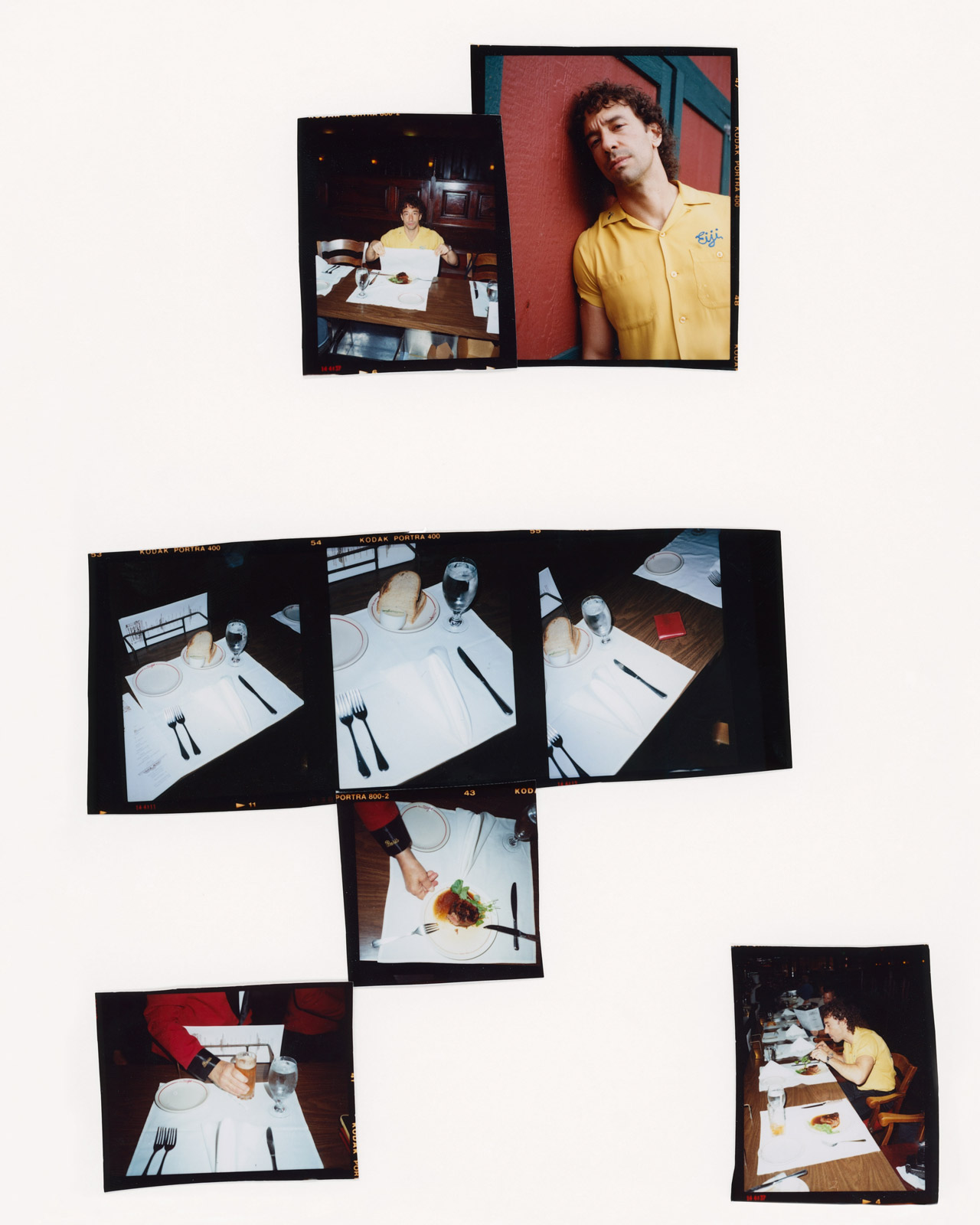

Melodies on Hiatus is actually intimate, littered with personal pieces of Hammond Jr’s own life. But, lyrically, the tracks went through a filter—pop songwriter Simon Wilcox, who distilled his thoughts over the phone—and the vocals are largely engulfed by the music in the mix. (“I like things loud,” he notes, musing on how the album will translate to its live counterpart, “so it’s going to be deafening.”) The album is his “life, sonically”: largely built from happenstance, and embroiled in emotion.

Despite the critical and cultural acclaim of The Strokes, a band more than well-cemented as a scene-making piece of music history—and of which he is a founding member—Hammond Jr still feels like he’s “trying to ‘make it.’” Melodies on Hiatus is his fifth solo record, and maybe his best shot at that, by its sheer ambition: It’s immense in length (with 19 songs, previewed in a nine-track drop); the most experimental of his works (which it sort of needs to be, given its aforementioned length); and features material written across the five or so years since he released Francis Trouble.

Following the release of Melodies on Hiatus, Hammond Jr joins Document to tease at a few of the meanings behind the songs, and justify his resistance toward doing so.

Megan Hullander: Beyond the more explicit differences in sound, where does this record depart most from your previous works?

Albert Hammond Jr: I never wanted to be a solo artist. I always wanted to be in a band. And I think my first records were kind of me fighting that. I was trying to hide myself in my name, which is weird. It wasn’t really until Francis Trouble that I was like, You know what? I’ll just sit here as myself here and be okay with it.

Megan: I would almost think that performing solo under your name, rather than as a part of a band, or even under a moniker, would free you up for more experimentation—like, there’s less of an expectation of persona or even continuity, because it’s you and not some project with an alleged purpose or personality.

Albert: What’s your definition of experimentation, you know? Even if you’re not [working within] the politics of a band, there’s a bigger picture. You’re still trying to make something great. Maybe experimentation is just learning how to craft multiple things that you’re normally a fifth of. But freeing? I don’t know about freeing. There’s a lot more you have to do and face.

Megan: You’ve said before that you’re uninterested in explaining your lyrics to your audience, so when you say you want to make something great, is that greatness not attached to lyrical meaning?

Albert: When I listen to music that I love, I don’t care for [the artist] to explain what they were talking about. The song has become my own thing. When you’re just doing press for a record and they’re like, ‘Explain what you did’—I don’t know. I’m making music because I can’t explain it; I’m chasing an understanding of myself. The right words, with melody, can feel powerful. And so you want to know what it meant. But it doesn’t really matter what I meant to say. There’s a song called ‘Darlin’,’ and in the chorus, I sang, ‘I’ve been alone for a long time.’ I don’t know why I sang that. I could get into whatever I’m going through, and [figure out what it meant], but it just felt like it worked. And we all understand that feeling [of being alone]. Does that mean that I was literally sitting there alone for a long time? I don’t know—and that’s boring. Writing is more like you’ve absorbed all this stuff in life, so you have little tools, and then they pop out when necessary.

When I was writing with Simon, we had long conversations. So things did pop up. ‘Downtown Fred’ is a part of my personality, of my persona. Or, like, there’s a line in ‘100-99’ that says, ‘I’m not safe/ I’ve made mistakes I would again / In spite of what it cost me.’ That’s the story of my fucking life. That is powerful to me. It just feels very human.

Megan: How were those conversations with Simon structured?

Albert: Conversation isn’t ever really linear, right? I had random gibberish and some lines, and was like, This is what I feel like it means. And [she was] like, I don’t think it means that. She had to interpret it in her own way. A good example is ‘Never Stop.’ [Simon] had this whole idea for the song. And when she told me the idea, I didn’t really get it. But when I read the lyrics, I was like, Holy shit, this is amazing. This battle, this guy who will never stop no matter how many failures [he faces]. And there was something very moving and powerful, but also silly to it. Sometimes, I feel like she’s talking to me [in the songs]. And that’s what’s so cool with lyrics and melody: When they’re in the right place, you can get lost in them.

One of my favorite songs is ‘Street Hustle.’ All the things [Lou Reed] says, are they true? Is he just a good writer? At the end of the day, I don’t know if it matters if you’re not feeling anything. It’s not school—we don’t need to explain the book.

Megan: In a statement about the record, you wrote, ‘This is this guy’s life, sonically.’ Why do you refer to it in that way rather than as ‘my life’?

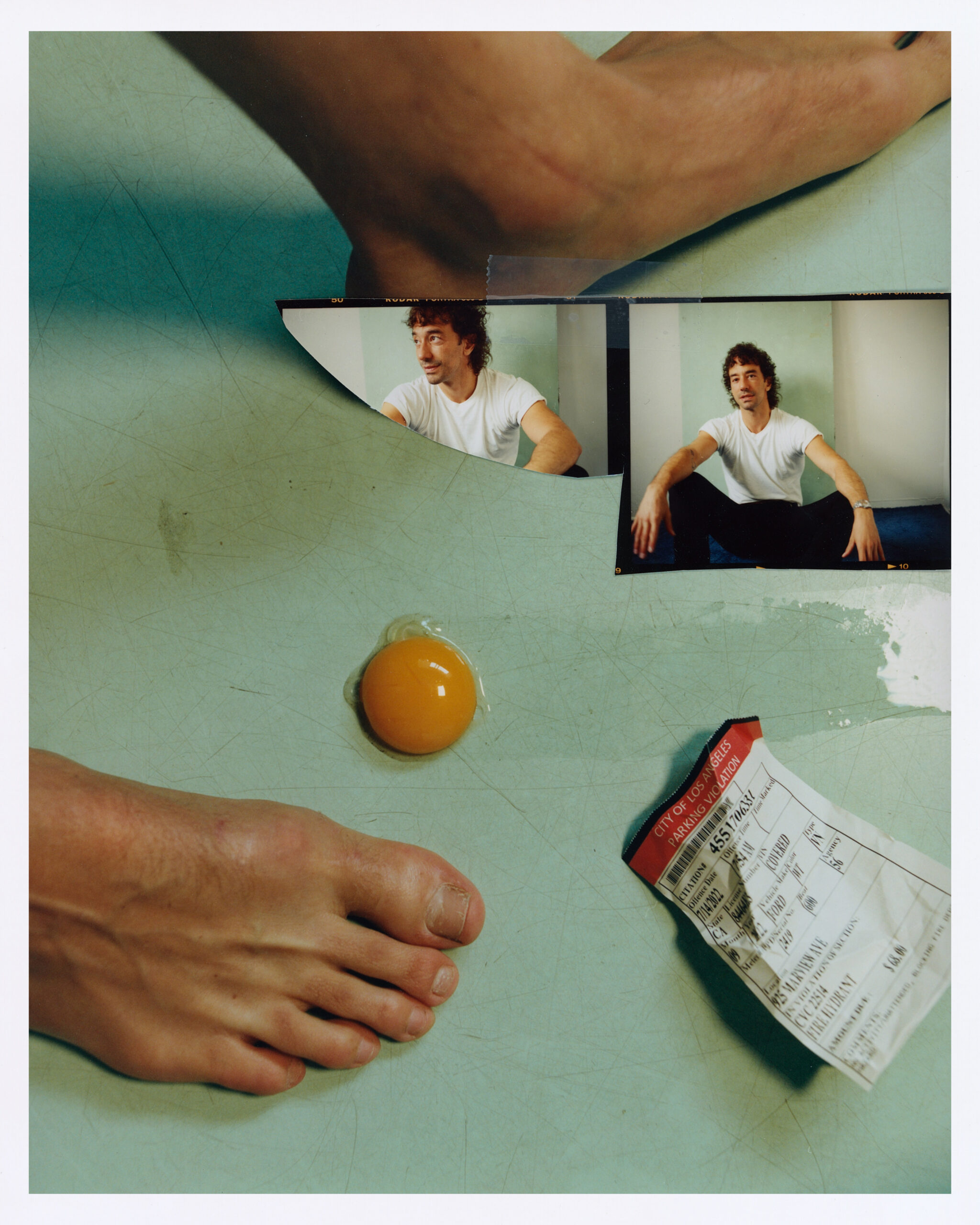

Albert: Sometimes, it feels too personal. I could probably dive deeper into it years later, because it’s digested. And who knows? Maybe I should just be balls deep [in it] right away. I mean, [when] you take on a record, your ups and downs are extreme. By the time it comes out, what you’re connected to is the next thing you’re doing, because you’ve done that. So you can listen back and enjoy the moment; like, Oh, that was so cool that I did that, or how I did that. But if anything, it kind of starts triggering ways you want to go next. It’s almost like a life in the past. I live in the process. People are listening to stuff that’s my past. [On] this record, strangely enough, that might have changed. So many things have happened in my life since I started it, and it still works—it’s even more powerful. It’s almost like I predicted stuff.

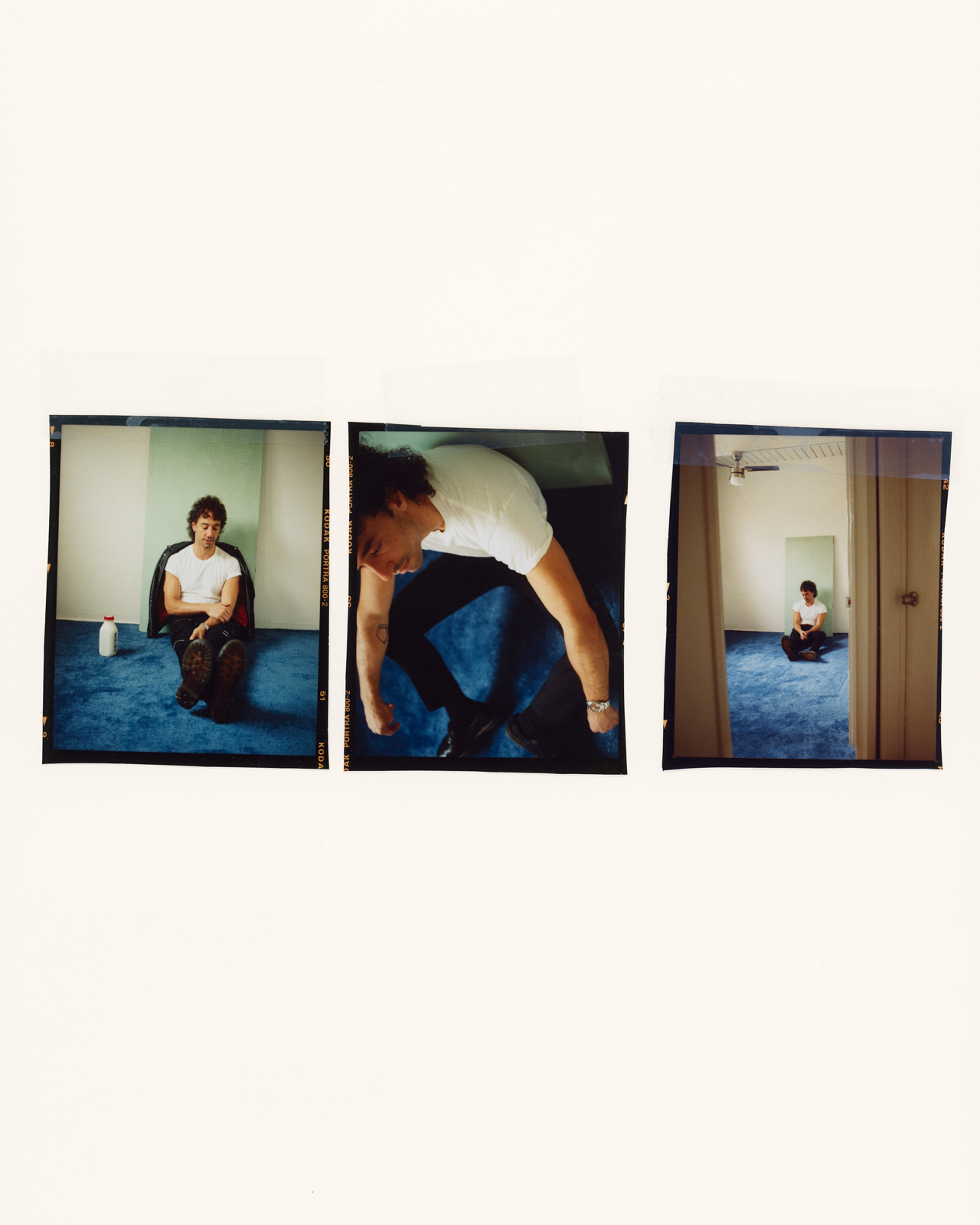

I imagine sometimes you might feel [detached from the songs] because you’ve performed them and heard them so many times that it’s just like a piece of homework. When I was creating it, I had strong feelings of understanding and purpose—like chasing the dragon. Other times, it can feel like, Why am I doing this at all? I don’t belong here.

Megan: Has your sense of purpose changed?

Albert: I don’t know if it ever changes, but the stakes are higher. They always tell you to just fall in love with the process, because the process of creating is really all you have. Everything else will always be the same. You’re always trying to make it somewhere. Even if you’re playing large shows, on your next record, you’re trying to do something else. Maybe the ambition is different when you’re young—the game is different. Because you don’t realize that there is a game to it yet. It’s a different kind of innocence, but I don’t think it changes. I still feel like I’m trying to ‘make it’ in many ways.