Document spoke with a few of the fair’s innovative makers, celebrating the heritage of weaving, millinery, metalworking, and more

Last Monday, London Craft Week returned for its ninth edition, spotlighting the work of more than 700 creatives and originating a slew of eclectic workshops, pop-ups, exhibitions, and panels. From the traditional to the innovative, the work on view celebrated artistic communities across and beyond the city, providing fertile ground for inspiration, and exposure to new—or often overlooked—modes of expression.

Document fell in with the crowds, finding time to speak with those designers, artists, and industry leaders redefining craft for the present day: At the Sarabande Foundation, Megan Brown, Anouska Samms, and Martina Spetlova explored the art of contemporary weaving; Cubitts founder Tom Broughton hosted his own spectacle-making class; at Lock & Co.—the city’s oldest milliner—Awon Golding positioned her headpieces as one-of-a-kind personalities; and Lanxin Yang represented the London College of Fashion, showcasing utilizable jewelry design for the future. Here, they shed light on their methods, the marriage of tradition and technology, and the evolution of established craft into something distinctly modern.

Megan Brown, Jeweler

Document Journal: Your ancestry uniquely informs your work. When did you first become interested in carrying on your great-great-grandfather’s jewelry and weaving practice?

Megan Brown: During lockdown, I began working on a new jewelry collection. The designs I had created up until then had always been very sculptural, with a strong focus on flowing lines. It dawned on me that what I was drawing was fundamentally a weaving. In a way, my family’s legacy has [always] been influencing my path. It’s a powerful reminder of the importance of heritage and tradition.

Document: What draws you to metalwork?

Megan: My background in fashion design introduced me to working with fabrics and threads, but I found my true passion in metalworking. The detail that metal allows is unparalleled, and it presents an exciting challenge—recreating the delicate qualities of fabric with durable material.

Document: Do you consider your jewelry its own form of sculpture? Where do you draw the line between fashion design and artmaking?

Megan: Through my work, I explore the interplay [between] soft, flowing fabric and hard, durable metal—seeking to capture the delicate beauty of one in the enduring strength of the other. I specialize in hand-woven jewelry and one-of-a-kind silver sculptures that mimic the graceful drape and fluid movement of a textile. Fusing allows me to take a unique approach to metalworking, as I’m essentially drawing with gold. I’m able to capture the delicate textures and patterns of fabrics, and bring that artistic quality to my work: a woven piece of art, which I then shape and form into the finished sculptural design.

Anouska Samms, Interdisciplinary Artist

Document: Tell us about the family ‘ritual’ that fuels your work.

Anouska Samms: I look at the things we make literal and physical as a way to stay attached to family, heritage, and unknown identities of the self—but, most importantly, the ways we wordlessly communicate our love for others. I primarily look at mother-daughter relationships, taking my own maternal [ancestry] as a starting point; I come from a long line of gingers.

Across five generations of women, [my family has practiced] a seemingly unquestioned ritual of dying our hair red. There was this unspoken act, where everyone expressed themselves similarly through their hair. I was trying to create some alternative textiles by putting different materials through my sewing machine; I had been researching genetics and reading about hair. With my family’s strange ritual, it seemed to be the perfect material to express this connection—so through the sewing machine it went!

Document: What draws you to the organic materials you work with, human hair and clay?

Anouska: In looking at mother-daughter relationships, hair, weaving, and clay are extremely symbolic. Mitochondrial DNA is found within the hair shaft and passed down to a child from their pregnant parent. The warp and weft symbolize the tissues of a child’s body, woven into the womb of a pregnant parent.

Clay—a transformative matter that inherits the quality of the ground it’s removed from—can create vessels from the mundane to the ceremonial. I like to play on this idea of the ceremonial form, exploring the ways my own family has made a very literal expression of their bond. I tend to make strange, vessel-like structures, expressions of [the forms that] connection can take, passed [down] to different generations.

Martina Spetlova, Designer

Document: You have a background in the sciences. How would you say that influences your approach to design?

Martina Spetlova: I see a strong connection between the processes of conducting biochemical experiments and creating textiles. Both involve trial and error. I carefully consider the properties of materials, and how they interact with each other—always seeking new and innovative ways to work with them. My scientific background also instills in me a sense of precision, attention to detail, and a curiosity to push boundaries and explore interdisciplinary connections.

Document: Would you say that it relates to your affinity towards technology—in terms of the scannable chips you work into each piece, or even in your approach to sustainability?

Martina: Absolutely. In my approach to sustainability, I embrace a holistic mindset that considers the entire lifecycle of a garment. And by incorporating scannable chips, I can provide valuable information to consumers—empowering them to make informed choices and prolong the lifespan of their garments. These chips can guide them on proper care methods, encourage repair [over] disposal, and facilitate responsible end-of-life options. I am also a big believer in storytelling, and transparency [around every product] narrative. Technology invites my clients to interact with [their pieces] in a more meaningful way.

Document: What does modern craftsmanship look like to you?

Martina: It represents a fusion of traditional techniques, innovative approaches, and a deep appreciation for quality. It recognizes the importance of sustainability and ethical practices. It places value on responsibly sourced materials, eco-conscious production methods, and [the promotion of] transparency. Modern craftsmanship embraces a holistic approach that considers the social, cultural, and environmental implications of each design. For me, it is about creating pieces that are both timeless and forward-thinking.

Tom Broughton, Cubitts Founder

Document: What do you feel is at the heart of your craft?

Tom Broughton: I’d characterize it as craft for purpose, rather than nostalgia or tradition. So with our frames, it’s about using the best materials, and then making beautiful objects that can easily be repaired and renewed.

Document: Where do you take your inspiration from?

Tom: We’re lucky in that we have three centuries of spectacle design to draw from. But we often focus on British designs from the 1930s—the ‘Golden Age’ of UK optics—French shapes from the ’40s and ’50s, and mid-century silhouettes from around the world. I like the idea of taking enduring, iconic shapes and updating them for the modern wearer.

But really, inspiration is everywhere, spanning art, sculpture, nature, and design. Recent frames have referenced Bird in Space by Constantin Brâncuși, the Amazonian water lily, Ancient Egypt’s Eye of Horus, and the work of Donald Judd.

Document: Who do you consider your industry’s style icons?

Tom: I’d say anyone who proudly wears their spectacles should be considered a style icon. But some of my personal favorites are James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, Michael Caine in The Ipcress File, Le Corbusier, Smiths-era Morrissey in his NHS 524s, Jarvis Cocker in late-90s Pulp, and Iris Apfel. Oh, and Clark Kent—but not Superman.

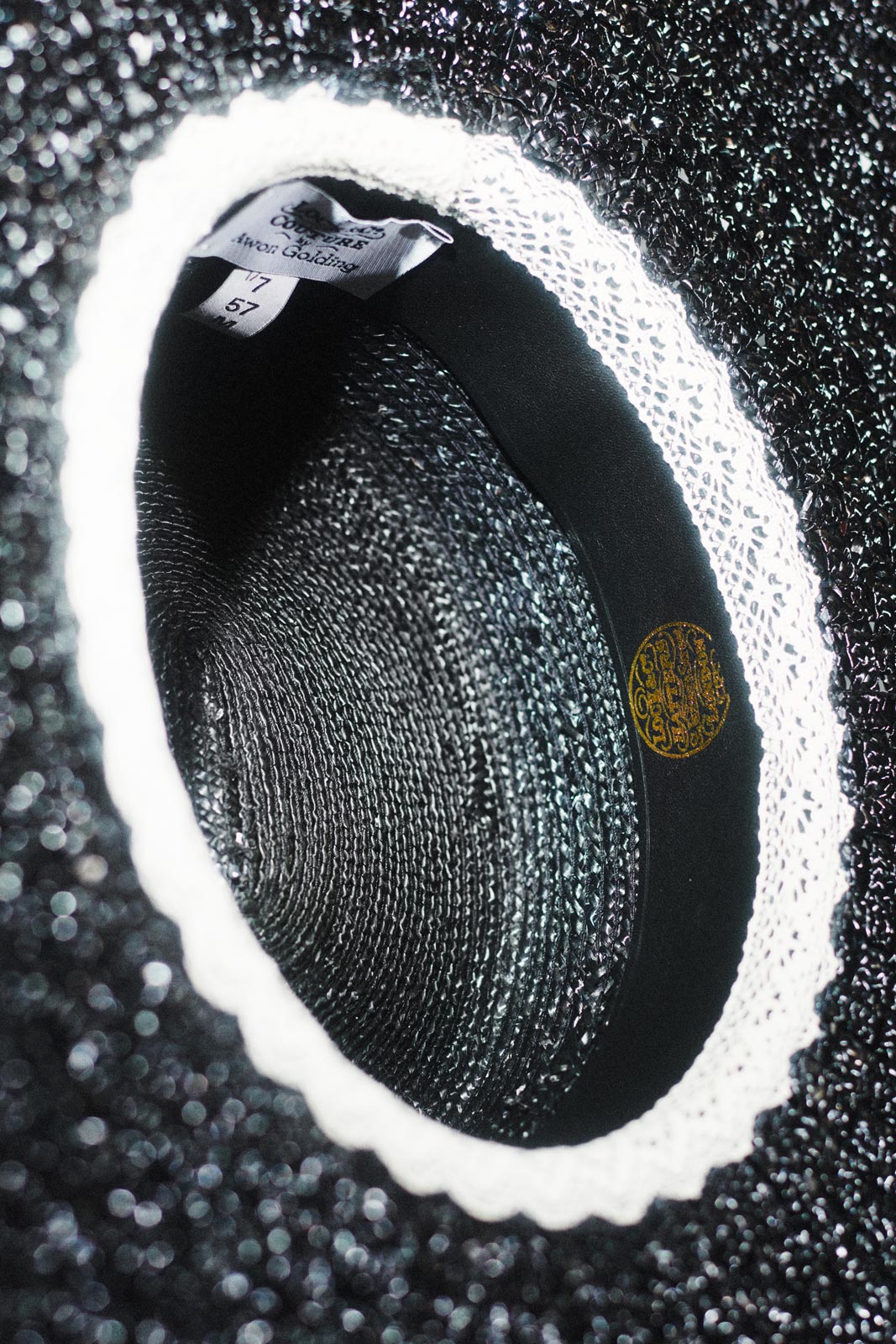

Awon Golding, Lock & Co. Milliner

Document: What techniques go into the creation of a Lock and Co. couture hat?

Awon Golding: I use traditional millinery techniques, such as blocking, hand-stitching, silk flower-making, and wiring. I use woven nylon quite a lot, which I cut with a soldering iron. As materials have changed over the years, so have techniques—they’re symbiotic, and constantly evolving.

Document: Each of your pieces is unique. Do you see each hat as having its own story?

Awon: More than a story. I see my hats as having individual personalities. Each one represents a mood or a feeling—something tangible and human. I always have the final wearer firmly in mind, so in some ways, that anthropomorphizes my designs. She’s sassy, or classy, or a party animal, or demure.

Document: Your hats uphold a sense of joy. In your practice, have you ever encountered a happy accident?

Awon: My first ever proper hat collection—back in 2014, for my own brand, Awon Golding Millinery—was a happy accident. The central work was a gelato headpiece, made from a giant ostrich pom-pom. At first, I had zero idea what I was going to do with the pom-pom; I just loved the shape. It wasn’t until I went on holiday to Italy that it came to me—most probably over a towering cup of gelati.

Lanxin Yang, Designer

Document: How do you develop each of your tools’ unique functions?

Lanxin Yang: In daily life, simple stretches and exercises for the fingers and arms—or for the whole body—can be used to keep corresponding body functions flexible. At first, I focused on the fingers and palms, studying the design of structures to assist movement.

Document: What do the materials you work with symbolize for you?

Lanxin: The shiny, metallic surface of brass is visually striking, and contrasts with its hard and cold texture. Glass is cold and fragile, but it is made through a process of melting at high temperatures; [its transparent shine comes from] a process of purification, of change—a hint for people to take action. Alabaster represents nature, the primitive, and tells people to keep their bodies in their original state of vitality.

Document: What’s behind your impulse to look toward the future?

Lanxin: Science and technology will reduce the [need] for human physical activity. I wanted to recreate a balance—physical and emotional—by harnessing technology, rather than being ‘controlled’ by it. Technology has developed into an extension of our bodies, and we can no longer survive without it. At the same time, as it becomes more efficient and people become less active, the human body is declining and losing strength. If such a lifestyle continues, we will not be able to maintain our current capacity; for example, our fingers, arms, and other limbs will no longer be active. It’s going to be a scary future, so I’m looking ahead to a positive one.