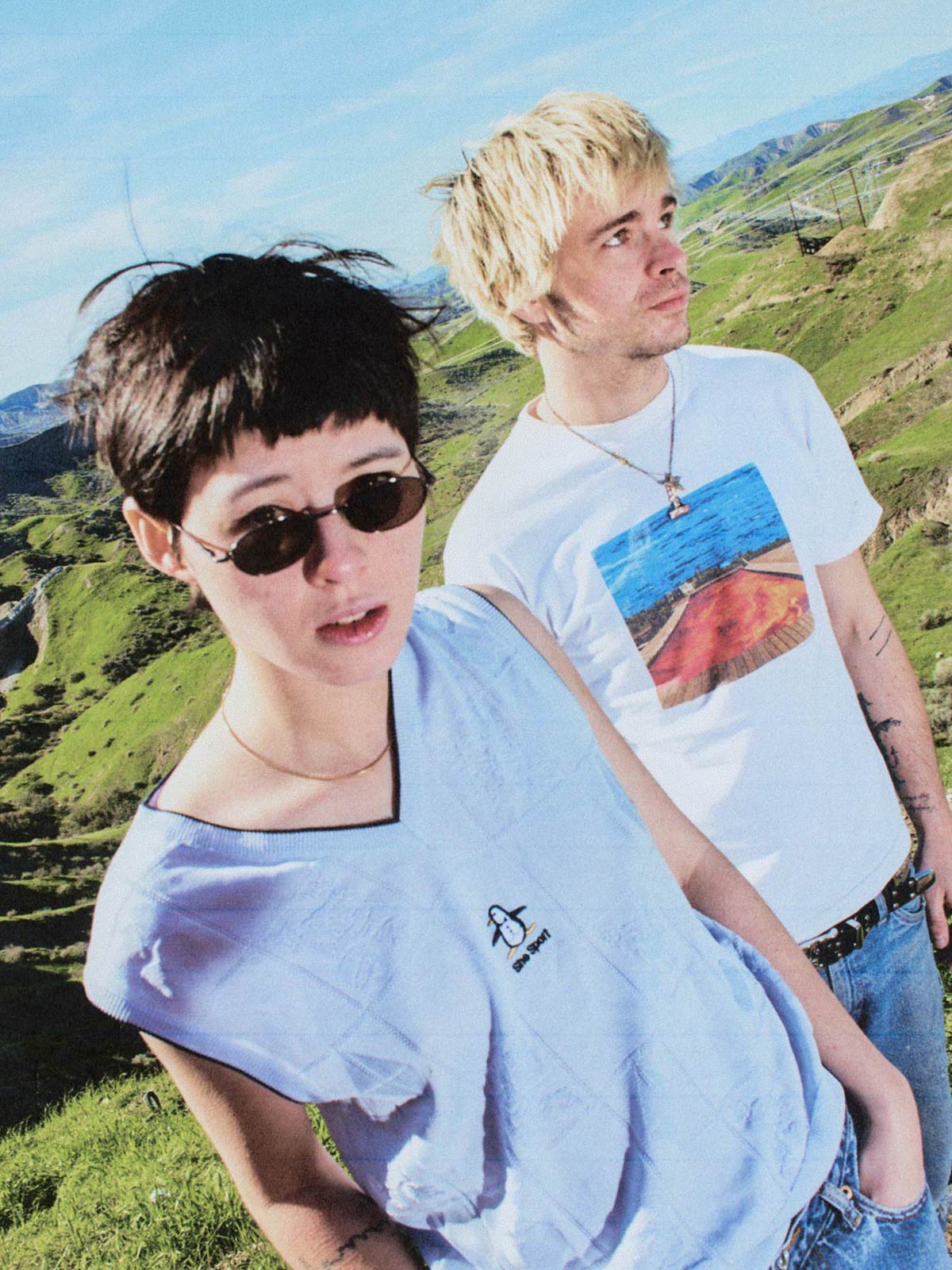

Ahead of the release of ‘Everyone’s Crushed,’ Rachel Brown and Nate Amos join Document to unpack their unintentional self-prophesying and extrapolate the record’s many meanings

Rachel Brown and Nate Amos aren’t comedians, they’re just instinctively funnier than you. Humor has been the centerpiece of the critical acclaim Water From Your Eyes has thus far received, but that’s only because most people making music today are, largely, unfunny, favoring reputations of hyper-seriousness and hyper-intellectuality over being true to life—which is actually pretty fucking funny sometimes. Amos elaborates, “The things that are funny are just as much part of the tapestry of human experience as things that are sad. It’s not comedy, it’s just trying to cover the whole spectrum.” Simply put, the duo isn’t trying to make you laugh, they’re just not trying not to make you laugh.

It’s maybe the rampant lyrically winks across their albums that might signal that a sense of humor is a primary point of their identity. (Their latest, Everyone’s Crushed, features a song about how Neil Young won’t let them rip his song.) Or maybe it’s that when they sense that an audience might not be receptive to them, they lean into that; opening with a 10-minute-long noise song for a less-than-eager set of Spoon fans, for instance, is an act of defiance against the unwillingness to succumb to the experience of their live show. But they are, in practice, more akin to Ween than they are Tenacious D: Quality and concept reign supreme, and the comedy is just a garnish to the greater meal that is their music.

But comedy actually is the only thing that the band attributes any real intentionality to. The rest, they (probably exaggeratedly) explain, is mere coincidence. It’s all built for the sake of what sounds good in the moment. All that is ripe for analysis finds its way to them after it’s been actuated. Ahead of tomorrow’s release of Everyone’s Crushed, the duo join Document to unpack the self-prophecies they’ve “accidentally” written, and extrapolate the record’s many meanings.

Megan Hullander: When you’re writing, are you pulling references from memory as you go, or do you go into the process with a sort of list of things you want to touch on?

Rachel Brown: ‘Barley’ references Sting’s ‘Fields of Gold.’ I had written a bunch of stuff, and at one of the last parts, Nate was like, That’s from that Sting song. Then, we listened to ‘Fields of Gold.’ And we were like, What if we just ripped words from the song and put it in our song—but not enough to, like, be sued? Sting’s sued so many people. We went back into everything that I’d written, and just replaced a bunch of the words with words from ‘Fields of Gold.’

Nate Amos: We kind of ran with that concept. It already fit, because in ‘True Life,’ there was originally an interpolation of ‘Cinnamon Girl’ by Neil Young in the bridge, and then his lawyers wouldn’t let us use that. So we changed it to be about how Neil Young didn’t want us to use his lyrics. And there’s a Sublime reference in ‘Buy My Product.’ There are a couple of playful allusions. And ‘Barley’ namedrops 311.

Rachel: That’s not on purpose.

Nate: I thought that was on purpose.

Rachel: You had it as some other number. Not that I love numerology, but I think it’s interesting to some degree, and 11 is, like, one of the more powerful numbers in numerology. Nate is actually an 11.

Nate: I’m a double 11. One time, I was briefly seeing someone who was into numerology and the fact that I was a double 11 freaked them out. I never saw them again.

Rachel: Yeah, exactly. I just thought, If we’re gonna choose a random number, it should be 11. But we also—maybe we use a strong word—but at the time, Nate liked 311.

Nate: I still like 311.

Rachel: I have a lot of respect for 311. They’re so crazy. But originally, it wasn’t [written in] because I liked 311.

“I think that’s how life works: Meaning kind of just finds you. There’s something more beneath the cracks of everything.”

Megan: It seems like you both often emphasize that things in your music come about incidentally or without any meaningful intention. But simultaneously, every small thing has an abundance of meaning that you’ve later attached to it.

Nate: I think that idea of embracing accidents and coincidences is something that runs through a lot of this project. That’s very much how the music gets written: doing random things until there’s some weird little click between two ideas. We weren’t like, Let’s sit down and write a song with a bunch of lyrics from ‘Fields of Gold.’ It just kind of happened, and we chased it down. That’s kind of how the whole project is approached—to a certain extent: You can attach meaning to it, but you don’t have to.

Rachel: With all of our songs, after we start performing them, then there’s meaning, then all the lyrics make sense and directly relate to my life. But only after the fact. It’s funny, because when I wrote it, it was just some words. I think that’s how life works: Meaning kind of just finds you. There’s something more beneath the cracks of everything.

Megan: And you’ve toured with some heavy hitters, like Interpol and Spoon, whose music is pretty different from your own. How have you found the reception to be with people who weren’t familiar with your music?

Rachel: Big range.

Nate: Yeah, it’s kind of a toss-up.

Rachel: When we went on tour with Palm, I think that just made the most sense with their fanbase. When we’ve opened for Interpol, some of their fans are like really into it. But their fans send us the most hate. You know that meme of Managers don’t like the vibe I bring to the workplace. Well, Interpol fans don’t like the vibe we bring to the Interpol show. People will tag us, which I think is funny. Like, ‘I flew all the way to Spain to see Interpol, and also Water From Your Eyes is the worst thing I’ve ever seen in my life.’ I retweeted that. The last show, somebody sent us a direct message on Instagram, between our set and their set, that was just like, ‘Call it a day, mate.’

Nate: I think we responded with like a selfie.

“This band has an identity that neither of us would have devised on our own. It’s this thing that has its own life and we just follow it around.”

Megan: Do you find that the music reads differently depending on the size of the space?

Rachel: We don’t change anything.

Nate: This band has an identity that neither of us would have devised on our own. It’s this thing that has its own life and we just follow it around. I think a big part of the way that has happened is just by being really uncompromising when it comes to conforming to any particular idea or particular space. So I think if anything, we tend to be more aggressively whatever we are if it feels like a space that would be less receptive to it. We opened one set [on tour with] Spoon with a 10-minute long repeating loop song of noise. People really hated that. Someone wrote this multi-paragraph thing that was just like, ‘I like cannot even explain how horrible it was. It was the most insultingly bad set I’ve ever seen anywhere in my life.’

Megan: Comedy is often referenced as very integral to the concept of this project as a whole, is that something you are really consciously trying to insert?

Nate: The things that are funny are just as much part of the tapestry of human experience as things that are sad. It’s not comedy, it’s just trying to cover the whole spectrum. When we talk to some people about it, they’re like, So, it’s supposed to be a funny band? And it’s not. I think a lot of music takes itself very seriously. And I think when you look at bands that have incorporated humor—even if it’s not the dominant thing—that’s the main talking point. They’re just as many not-silly aspects, but because there’s a spark of humor to it, they get lumped in with, like, Tenacious D. The point definitely isn’t to write something that’s ha-ha funny. It’s just not to exclude the more humorous ideas that come up.

Rachel: We’re so funny, we just can’t help ourselves.