On the island of Bequia, the designer transforms plastic waste into works part textile, part sculpture, and part performance

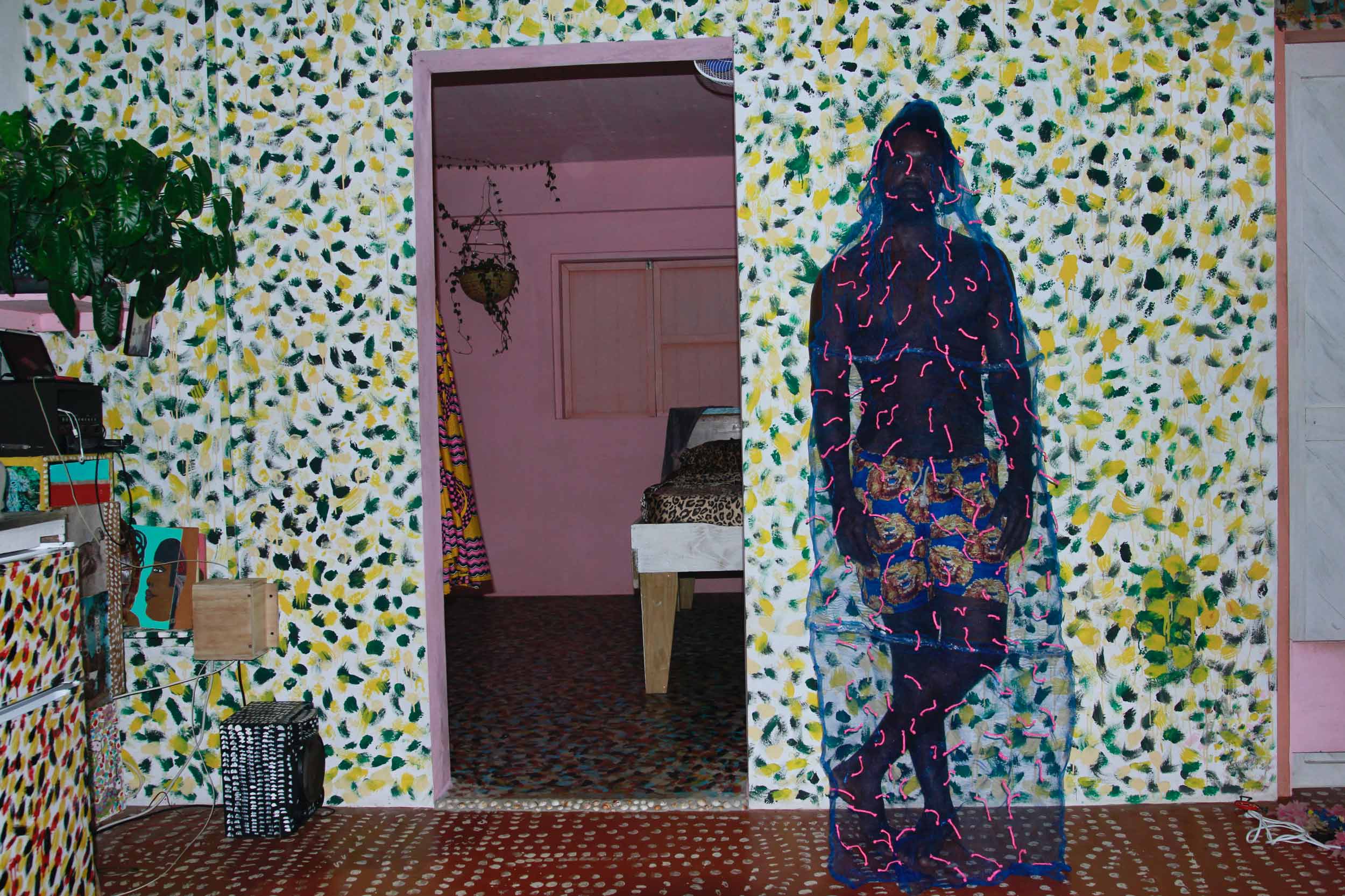

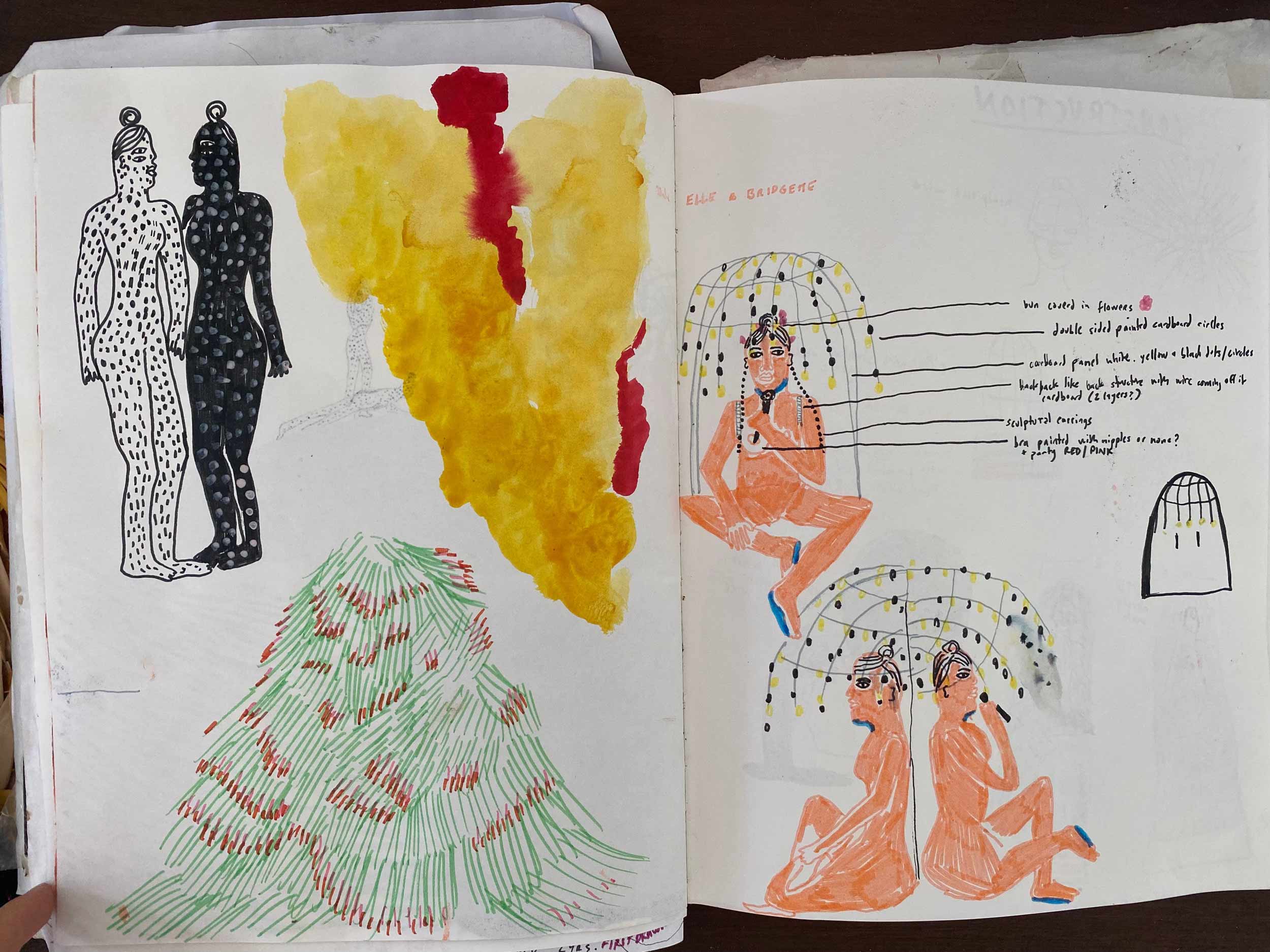

Backed by a muted sunset, a subject wears a blue veil that appears luminescent, adorned with tassels. In a desert scene, another body is covered by what seems like a feathered robe. Lila Roo’s garments, however, necessitate a closer look. What from far away looks like feathers turns out to be plastic—the same as the veil and the tassels. An inspection of Roo’s portfolio reveals that everything is made from discarded materials.

Working from the island of Bequia, part of the Grenadines, Roo collects materials that have been thrown out, transforming them into works that are part textile, part sculpture, and part performance. The island is less of a tourism hub than others nearby, and Roo’s life there is deeply intertwined with the land. Still, inhabitants inevitably make their mark. Roo’s criticism of the overconsumption of plastic is evidenced in her pieces: They function as an inversion, reconstituting the materials in new products, made more beautiful in the process.

In this way, Roo’s work subverts traditional expectations of how artists talk about place. Instead of depicting island life, the designer preserves the unwanted detritus the island has tried to get rid of. These pieces are then reincorporated into local life, worn on people or displayed in the landscapes. Through highly imaginative use of material, Roo’s work extends beyond a simple environmentalist lens, commenting on the intangible byproducts of human existence.

Alexandra Bickerdike: What’s life on the island like?

Lila Roo: Colorful, raw, real. Illusions don’t go very far here. This place shows you your greatest strengths and weaknesses, and keeps you humble. It’s slower than the big world—and yet, in the slowness, lack of distractions, and limited resources, there is infinite depth.

I live in the fishing village my husband, and generations of his family, were born in. It’s a tough and loving place, and one of the last sovereign strongholds on the island that isn’t marketed for tourism. My days: I take my son to and from preschool in a commuter van that blasts dancehall, walk home in the heat, work on my art for as long as I can, grumble at doing housewife chores, work on more art, drink beer on the street with everyone on the weekend. Our family just hand-built a wooden fishing boat named Lion Order which has become a vessel of work, exploration, and freedom. It looks like a leopard racing through the blue water.

Alexandra: How do you channel the energy of the people into your practice?

Lila: My art is always a reflection of my life: the people I love, the environments I am in. When I make work for people, I focus on the strength and beauty I see in them—energy beyond the physical things that define us. I feel like day-to-day functioning is a limiting world that doesn’t always offer ways for people to express their dynamism and depth. Adorning and transforming your body is an age-old practice that allows people to find or express other parts of themselves.

Alexandra: Your making process feels like an expression of love, for people and for our planet. How were you first influenced to start creating?

Lila: I am a deeply visual and sensory person; that is how I take in information. Creating art has always been my way of communicating—my language—and I have been doing it since I was a kid.

My love is invigorated by that which angers and repels me, too; it’s that contrast and challenge that propels it. I’m working with the discarded products of amplified consumerism and exploitation. Transforming this material into something unrecognizably beautiful, through the energy of my own hands—it’s a philosophical challenge for me as much a physical one. It’s about tapping into the alchemy of life through transformation, reminding me that things aren’t just as they seem.

“I think true environmentalism is looking at our unquenchable thirst to consume, own, and exploit things—people and nature.”

Alexandra: Do you have any sourcing or making rituals that you like to carry out within each project?

Lila: I walk a lot, sourcing and collecting materials. And when the inspiration hits, I work laboriously—stripping, braiding, melding, without much stopping. I usually listen to the same music on repeat for an entire project. Through that repetition in my hands, for days and months, I build a kind of energy and vision for the project. Once I am immersed, it becomes a safe and creative vortex, and if I interrupt or leave that space, I become self-conscious, and too ‘human’ again. When projects are performative or photographic, I try not to talk much, and just see what reveals itself in the moment. The mystery of what comes out, from myself or other people, is always really exciting to me.

Alexandra: Your practice exists at the crossroads of environmentalism, fashion, sculpture, and performance—what is at the heart of each art piece?

Lila: Contrast, duality, beauty and ugliness, the revered and the discarded—and how these things are all connected.

Alexandra: What is its main aim?

Lila: Staying sane. Communicating the holism that I see and feel.

Alexandra: How do you want people to feel when they view your artworks?

Lila: I hope people feel opened up; my work is not something you have to understand or know fully. I want people to feel inspired and curious, and not to consume it or define it too quickly.

Alexandra: How would your practice’s focus shift if all plastic pollution stopped?

Lila: My practice is more about transformation than the actual materials I am using. I imagine that, without plastic pollution, I would continue to transform other materials that would otherwise be discarded. I find human consumption and waste deeply disturbing and fascinating.

Yes, plastic is an awful material. But consumption itself is the heart of the problem. I think about this a lot, living on a historically colonized West Indian island. Pollution is bigger than going green with our products. I think true environmentalism is looking at our unquenchable thirst to consume, own, and exploit things—people and nature.

Alexandra: Do you feel your practice has prepared or inspired you to work with other mediums in the future?

Lila: I would love to work more in film, performance, and sound to capture bigger, more sensory experiences. I feel this current facet of my artmaking is just the beginning of what I want to create.