Founder Ben Gorham sits down with artist Dozie Kanu, discussing the geography of his oldest and most recognizable fragrance

Ben Gorham, the perfumer and founder behind the luxury fragrance and lifestyle brand Byredo, originally concocted the scent Bal D’Afrique as a love letter to Africa. Gorham—who was born in Sweden to an Indian mother and a half-Scottish, half-French Canadian father, and raised between Toronto and New York—discovered the journals where his father recorded memories and observations from a decade spent in Africa. Gorham visualized the journey, the freight ships and the mélange of faces and personalities, dreaming up Bal D’Afrique.

Bal d’Afrique (African Ball in French), a warm floral scent composed of African Marigold, bergamot, buchu, cyclamen, violet, Moroccan cedarwood, and vetiver, debuted in 2009. To pay homage to one of Byredo’s oldest and most recognizable fragrances, Gorham tapped artist and designer Dozie Kanu, based between New York and Portugal, to create the brand’s first presentation during Milan Design Week. Born and raised in Houston, Texas—Travis Scott was a classmate, and is now a fan—to Nigerian parents, Kanu came of age straddled between his American and African identities, with a longing to discover his ancestral homeland. In 2018, at age 24, Kanu took matters into his own hands, purchasing a ticket to visit his father in Nigeria. Since then, he’s also traveled to Ghana, and most recently to Dakar, Senegal.

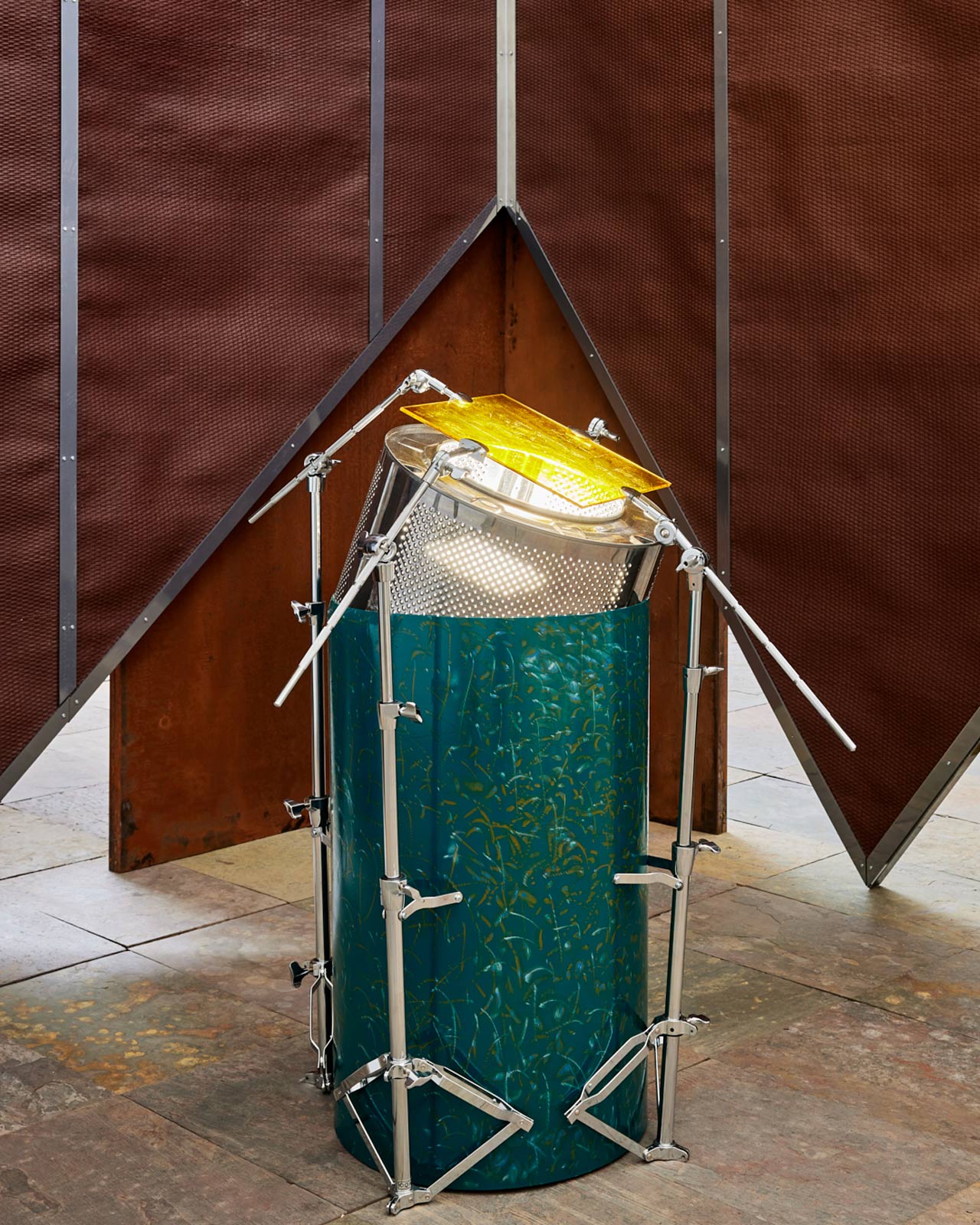

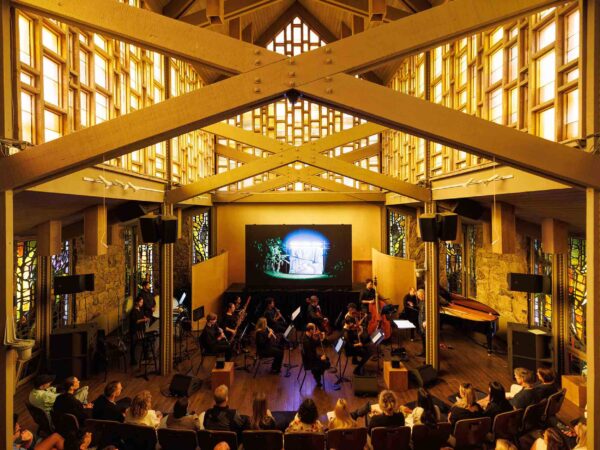

Bal d’Afrique by Dozie Kanu is a celebration of more than just the fragrance; it’s a tribute to Africa, and those who make up the African diaspora around the world. Situated at Milan’s Spazio Maiocchi through April 23 during Salone del Mobile, Kanu’s installation begins with a vitrine filled with photographs of Africans, collected from the Saman Archive. Visitors walk down a long hall, observing scenes of everyday life, vibrant Ankara and kente prints bursting with color. Kanu’s first architectural structure, a pavilion of weathering steel, glass, aluminum, wicker, and stone, was inspired by his recent trip to Senegal; he invites visitors to enter and observe various elements of his multidisciplinary practice, from a series of beaming lights made with found washing machine drums, to a red table that uses giant steel pipes for legs, to a gridded seating area, adorned with bamboo stalks.

Gorham and Kanu met on the opening day of the installation to discuss being raised by immigrant parents, their impressions of Africa, and how the late Virgil Abloh—who had a 2018 Byredo collaboration—influenced this project.

Ben Gorham: At Byredo, we were looking at the larger body of work we’ve been [creating] for 18 years. A few of those projects stood out; Bal D’Afrique was one of them. I wanted to revisit the narrative, how it evolved throughout time. Dozie was one of these people in the culture, in the community. Virgil [Abloh] was, too. This is a love letter to Africa.

Dozie Kanu: As I got older, and as I got to know myself more, I started to really embrace my African heritage. When Ben extended this invitation, I was at a point where I was fully ready to dig in. When I was younger, I was constantly trying to hide my African heritage, because it was just another way of excluding me from being a part of Black America. Kids are harsh, you know, they diss you. But as I got older, I really just wanted to embrace it. This was a beautiful opportunity to fully dive in, and bring to the surface everything about me that I’ve been suppressing for so long.

Ben: Do you think that’s changed in America? Because I’m older than you, and I went to an all-Black and Spanish high school.

Dozie: It’s definitely different now. If I were to grow up [today], I might be cooler for being African. I don’t know what happened. There’s just more awareness.

Ben: In the communities in which I grew up, Africa was a very foreign idea, even in Harlem. A lot of people didn’t know enough about that heritage. It’s the same thing, you know, for Indian communities. My parents’ generation, they almost overcompensated in assimilation.

Dozie: I don’t speak [Igbo or Ibibio], because my parents really wanted me to integrate. But as I got older, like I said, I really wanted to get down to the roots. I took the initiative to go to Africa for the first time: I paid for my ticket, booked my hotel, and went to see my dad, who had been living there for the past seven years.

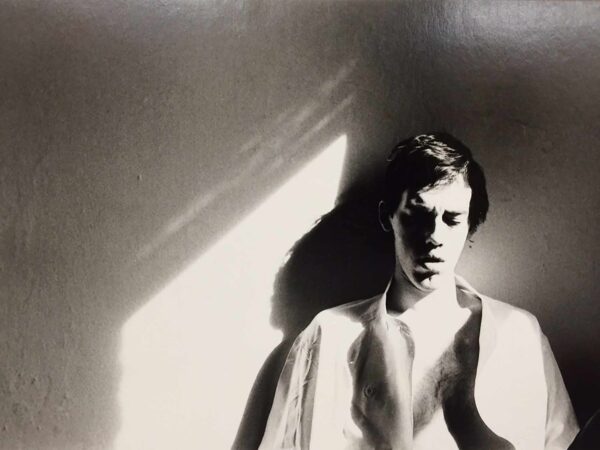

Some of the photographs that are in the exhibition are actually from my first trip. The reason why I’m able to see the beauty in some of these things is because [I have] such distance from them, conceptually. I’m able to have a different perspective, because I was raised in a different culture.

Ben: I think this experience relates a lot, because Bal d’Afrique is really a wide-cast net of stories relating to the continent. The diaspora today is much more connected than what we were seeing when you were growing up. And a young child in Houston, [raised by] Nigerian immigrant parents, was probably not thinking about creative explorations in Nigeria, whereas I think they are today—partly because media and music and culture, these things are being integrated. As we were revisiting the narrative of Bal D’Afrique, [we thought that] Dozie could have a very compelling perspective when it came to the diaspora. And that’s what the work was centered around. From our side, it was a collaboration in the truest sense.

“Bal d’Afrique is really a wide-cast net of stories relating to the continent. The diaspora today is much more connected than what we were seeing when you were growing up.”

Dozie: I’m curious, was there ever a point where you were nervous about what I was gonna do?

Ben: No, because I knew your work. I don’t think I was worried once. The only thing that may vary [with collaborations], you know, is the type of communication you have. How constructive can a dialogue be? How collaborative can the creative direction be? I tried to give, in this case, as much space as possible.

Dozie: I felt pure freedom. I felt like you were giving me the green light on a lot of things. You never stepped in like, I like this or I don’t like this—

Ben: No, I said that kind of behind the scenes [laughs].

When I looked at Dozie, and Dozie’s potential, it was beyond anything I’d seen. So I felt more confident in a supportive role, because I know you’re on this trajectory. I’ve worked with other artists, established in age. I approach it a little bit differently, because they’re really at the upper echelon.

Dozie: Yeah, household names.

Ben: Not even in public perception. They’re producing at their capacity. With you, it’s getting you to truly see your potential. I felt like that was important.

Dozie: In [Virgil’s] passing, I’ve been able to get rid of a lot of the fears I used to have—of being on a platform that I felt like I didn’t deserve. I used to think that I had to hide, and let people discover my work slowly. There’s something that I envied in Virgil—always just standing front and center, unfazed, taking all the criticism, all the backlash. I could never do that; I could never just jump in front of a speeding bullet. Shortly after [his passing], you reached out to me, and I felt the spirit of him. I was like, I can’t say no.

There’s something to be said about the current moment we’re living in, in terms of being a young artist. There’s no clear path to success. There never was a clear path to success, but now it’s really, really fucked up. Because it’s so saturated, there’s so many ways to promote yourself. There’s so many ways of gatekeeping now. Doing this project, I want to step outside of these rigid structures that artists have to subscribe to in order to be accepted. I feel like I can do work in any context. I can do great work in any context.

Ben: You are very much like V in that.

Dozie: In essence. I have to stop being so worried that I can’t tailor any situation to myself. It is imposter syndrome. That’s one thing that plagues me, for sure. I want to deserve success, you know? I don’t want to stand on a platform that people think I didn’t earn. I always try to make my work resonate for that reason.

Ben: This process [has been] very fluid. It’s less about the smell; it’s more about the narrative, and the idea behind it. I think people can take smell in a very literal way. For me, it’s because it’s so subjective—it means one thing to me, and one to you. It’s more about creating the spark. Your mind starts to explore. I call that collective memory. It’s getting you to tap into what’s important.

Dozie: My mom loves it. You sent, like, a big care package.

Ben: I go to a Byredo shop anywhere in the world, and there’ll be 18-year-old girls and boys and grandmothers buying the same products. And that kind of still kind of blows my mind. Fragrance is unique in that sense. Smell relates to this very innate aspect of somebody. It’s almost DNA.

Dozie: In order for me to justify a statement piece like this one, I really wanted to involve a friend of mine, Adjoa Armah. She runs an archive called the Saman Archive. She goes and collects negatives from these photo development shops around Ghana that they’re [about] to get rid of. She has thousands and thousands of negatives and a team of assistants; they carefully curate what they think need to be salvaged.

Part of the richness of the collection of sculptures comes from the fact that they were made over the course of four years; it’s not like every piece is new, which helps a lot when you’re not trying to make a bunch of new work for a show. You can curate what you feel works together. You don’t really get a lot of that at Salone. It’s all pretty much new work or old stuff. The structure [of the show] came from my trip to Dakar, really wanting to do an architectural project. I studied set design for film and theater, so I had that sensibility. I wanted to exercise that muscle, and I had this amazing, ambitious, super capable company to help me.