The photographer and writer share personal images taken on Polaroid’s Bowie Edition film, meeting to discuss his unfaltering influence, and the ways it’s maintained today

Every life is comprised of a series of distinct worlds—of places and characters and jokes and tears that belong to those who occupy it. For some, these worlds are so enthralling they must be dilated, and dissolved of boundaries. David Bowie was a master of making his accessible to anyone interested, and in manifesting the worlds he imagined into reality.

More than his music, more than his style, more than his showmanship, Bowie’s legacy was founded upon a willingness to keep his identity in flux: to never hesitate to dive wholly into whatever caught his attention, regardless of how it—or, more likely, how it didn’t—fit into his existing image. That spirit is near-universally revered, but difficult to occupy.

CJ Harvey is one of the rare people who carry that spirit in its truest sense. For Bowie, music was the means of accessing and expressing those worlds; for Harvey, it’s photography. There’s an intimacy to each of their practices that can’t be forged, and a shared disposition to make their own realities. It’s even matched—as famed writer, educator, musician, and real punk Vivien Goldman notes—in both creatives’ self-sufficiency, built from the need to carve out spaces that don’t yet exist.

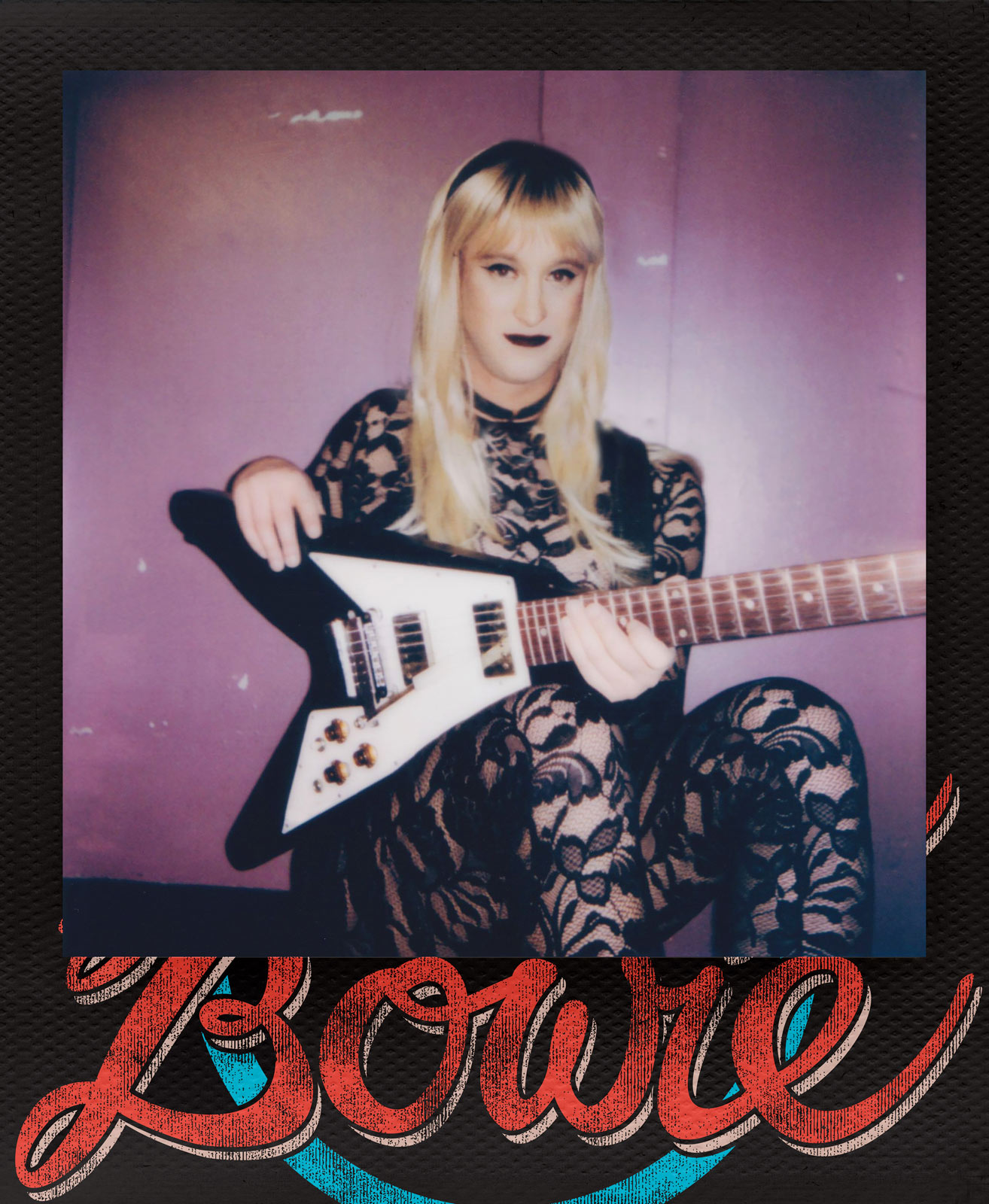

Film is Harvey’s preferred medium, for the intentionality it requires and the spontaneity it inflicts. It requires more risk—more faith in the self and the process. Polaroid photos, though, allow greater ease, or “the best of both worlds,” as Goldman observes. Their dreamlike quality is fortunately flattering, and there’s something distinctively pleasurable about their immediate access. The photographer thus felt an obvious choice for Polaroid’s launch of Bowie-inspired collectible film. Every image she captured aimed to match his essence—in the moments they were taken, in the artists that they captured. Goldman is an equally natural fit for the frames—not even just as a professor of Bowie at NYU, but in her enduring ability to experiment with different mediums, and her obvious love for sharing the joys that come from that creative play.

For Document, Harvey and Goldman share personal images taken on Polaroid’s David Bowie Edition film, meeting to discuss his unfaltering influence, and the ways that it’s maintained today.

Vivien Goldman: I remember being in my parents’ bathroom—I hadn’t even started dyeing my hair yet, which I have done from [the age of] 16 to now. ‘Space Oddity’ came on the little transistor radio. I remember the quality of light in the room, I remember everything [about that moment]. It was so transformative—it has this amazing sense of uplift and possibility. And that’s really what David Bowie represents.

He never stopped evolving. In this day, when everybody’s talking about cultural appropriation and authenticity and so on, you never hear anybody knocking David Bowie. All those pivots and changes were part of his magic. He kept on uncovering, discovering new archipelagos, and responding to them in music—but each song was unmistakably him.

CJ Harvey: Bowie’s not ripping anybody else off. It’s all unapologetically himself. There are a lot of artists who get stuck at a certain point in their career, and then they’re like, I can either keep making the same kind of stuff forever, because that’s what people expect from me. Or they try something that’s too different. And it’s not authentic. It just feels forced and staged. It takes a very particular kind of artist, like David Bowie, to be able to continually express themselves throughout the decades, with this whole realm that he created. It was always so much bigger than just the music; it’s about the drama, and the emotion, and the costumes, and this vibrant world that he created and invited his fans to be a part of. Had he not evolved that sound, and everything else that made him who he was, it probably would have [been] buried, because the rest of the punk community and the youth culture would have continued to evolve and left it behind.

Vivien: I was right down there in the center of the mosh pit of punk, in the first London wave. We despised everybody, but Bowie remains sacrosanct. The authority with which he managed to invest each incarnation was really riveting. He never wanted to be bored. He would rather take a risk—and if it comes to it, fall flat on his face.

CJ: But at least it’s never stagnant. You could drop a pin, at any point in his career, and think that that’s what he’d done forever—you would think that that’s his whole shtick, because he’s so immersed in what he’s doing and so expressive.

“I was right down there in the center of the mosh pit of punk, in the first London wave. We despised everybody, but Bowie remains sacrosanct.”

Vivien: And then the amazing thing, which elevated him as a star among stars, is the end of his career. When he did Blackstar—the final works, they’re so big, and transcendent. And you think of the generosity of an artistic spirit, who never stops questing and finding new teamwork and synergy to express what is clearly something prophetic of his own imminent demise.

When I was checking you out, Miss CJ, you did remind me of something Bowie. He was the first artist to take to the stock exchange and get people to invest in his future work. And it became huge. When I was checking out your website, I saw you’ve really got it down with your presentation to the marketplace, and finding your own independent position. You’re not just sitting around, it seems to me, waiting for one big client to call you up. You seem to be the person who’s using the conduits of today, and the alleyways and byways of the internet, to build your own constituency and your own market. [Bowie] went through an awful lot with management, and so on. And then, at a certain point, somebody said to him, ‘Guess what, David? Nobody can manage you better than you.’ Which he started to do.

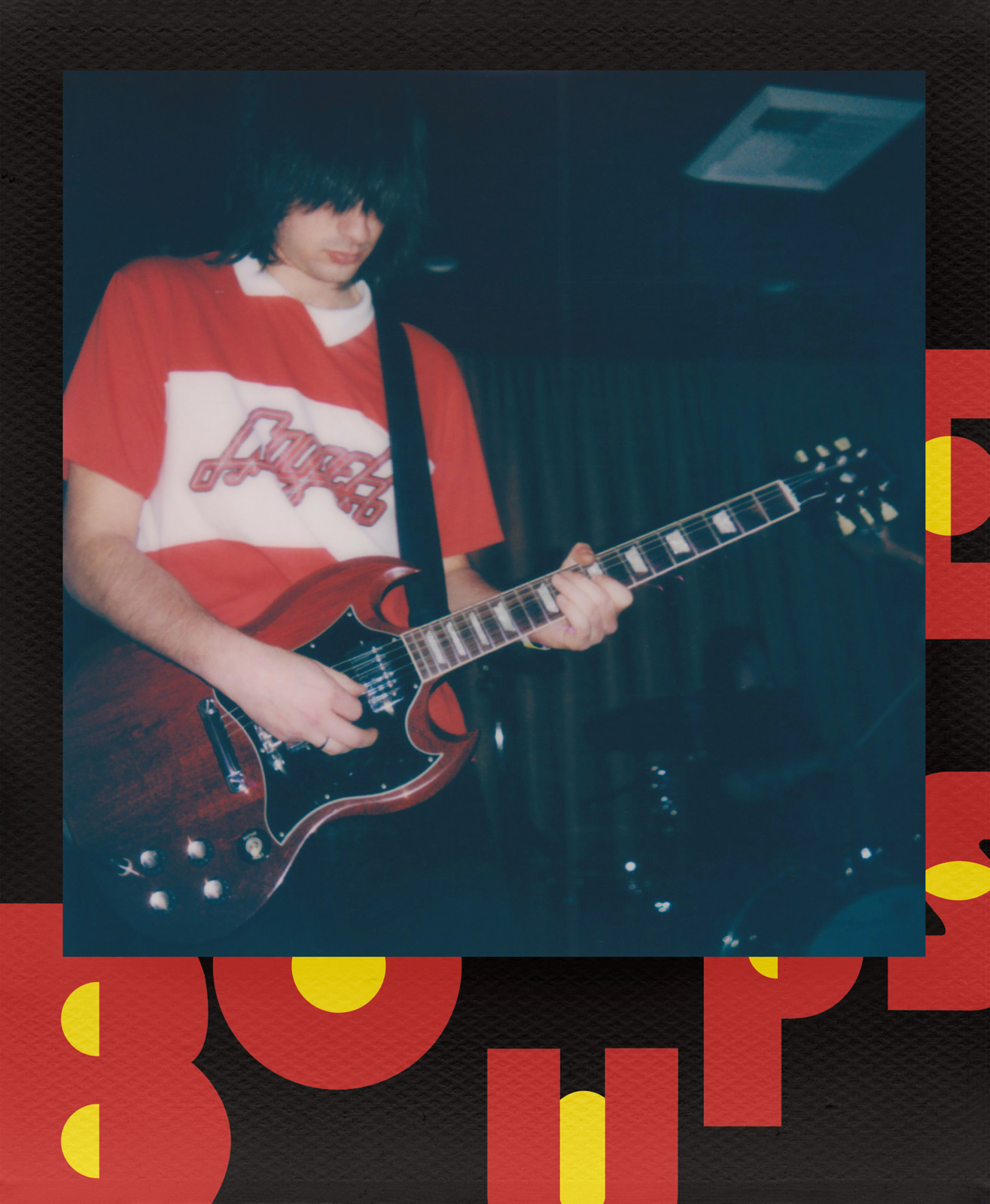

CJ: I think that, of course, you have to talk about the internet and Instagram when you’re talking about younger artists. It’s this tool that’s accessible to almost anyone who’s got a phone or a computer. I’ve never had a manager, I’ve never had an agent. When I started shooting in New York City when I was 18, sneaking into clubs and stuff, some of the first people to give me these opportunities were the bands busking in the subway. Starting with really small bands and having friends who are artists, you get really comfortable with your gear and learning the lighting and the environment. I love shooting on film, as well, and it takes a lot of trial and error to kind of get the hang of Polaroid cameras, because it’s not necessarily as straightforward as using a digital camera would be. I was able to use these smaller artists as my subjects to figure out who I was as an artist, what I wanted to express, and the style that I wanted to develop. If I could have it my way, I would never pick up a digital camera again.

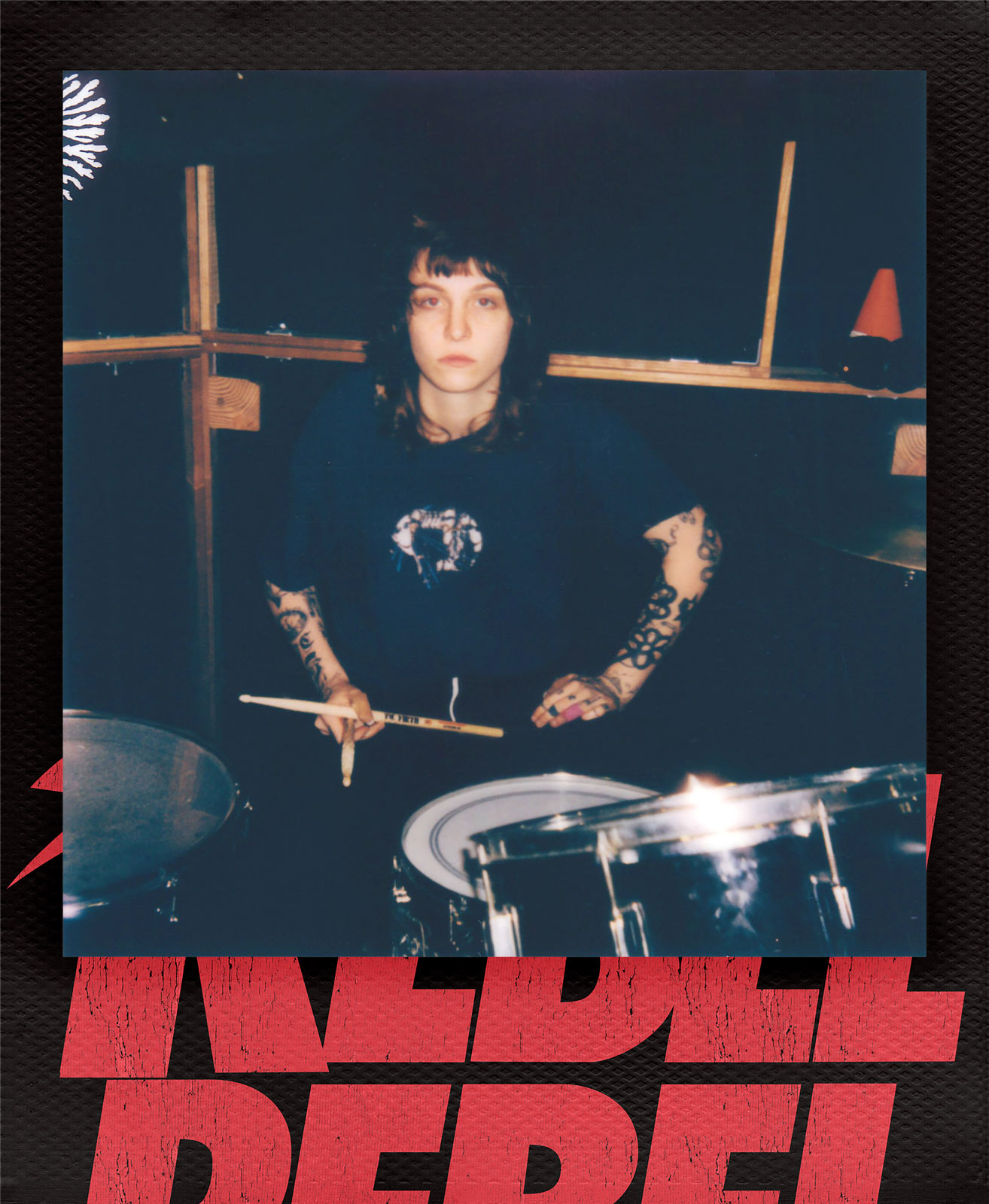

I’ve had a great relationship with the folks over at Polaroid for many years. And back in the fall of last year, they reached out to me to see if I would be interested in documenting some musicians on this special David Bowie Limited Edition film. They wanted me to document actual young, emerging artists who I thought referenced Bowie in their own work, and in their own spirit. I worked with two bands: Mannequin Pussy from Philadelphia, and Rocket from LA.

It was so fun to have the Polaroid film, because what you get is what you get. It feels like you have a toy. And you don’t really look at it until the very end of the night. Then you pull out this massive wad of 30 Polaroid photos that have been sitting in your back pocket. They’re a little sweaty, and you pull them out, and everyone’s huddled around you.

Everyone just looks good on Polaroid, too. It’s just a very flattering film to be shooting on. And people get so excited when it’s tangible. It feels like this very honest form of art, because it’s not this big, digital thing that you did in a studio with Photoshop and CGI and post-production—there’s none of that. No frills, no editing, no color correction. It’s not staged. That’s as close as you can get to honest documentation.

Did you shoot much in Polaroid back in the day?

Vivien: Not me specifically, because I was always working with amazing photographers and I sort of never bothered myself, because there were always mates documenting. Among them is my very close friend Jeannette Lee, formerly of Public Image Ltd, and now of Rough Trade Records. And she put out a book—which does actually feature yours truly, along with Johnny Rotten and everybody else—of her Polaroids. And the color often came out quite oversaturated—in a good way. You will find a sort of graphic intensity with those early Polaroid photos.

CJ: It’s the graphic intensity, but everything also has such a dreamlike quality, where it’s soft and hazy, and the highlights are a little blown out. It feels kind of glamorous to me. A Polaroid photo just makes anyone look like a movie star. Bowie encouraged younger artists to push these boundaries of their own individuality to express themselves in ways that far surpass their music.

Vivien: If he was on a shoot or something, instead of just retiring to his caravan or whatever, he would always make a point of talking to the kids on the set. ‘Where are you hanging out? Is there a new club? Let’s go together.’ That endless receptivity as an artist, and being open and listening and wanting to follow things is the way to keep being relevant, I think. Because you hear some people talk about, How do I stay relevant? That is the challenge if you’re committed to a whole life in whatever branch of art. Bowie shows us the key: Keep your ears open, don’t close your mind down, be honest.

“It feels kind of glamorous to me. A Polaroid photo just makes anyone look like a movie star.”

CJ: He never settled. He seems like the kind of person where nothing was ever enough for him. He always wanted to keep those doors open, like you said, and let the influences come to him from different types of people in different environments. He wasn’t just creating something new for the sake of doing something different; he was creating something new because it was relevant to this reflection of the world around him, and how things were changing in his actual life.

Vivien: And he took his people with him, didn’t he? He opened my eyes to all the possibilities. That just gave me the courage to explore. It doesn’t need to be eternal youth; it needs to be eternal creativity, eternal exploration.