Featuring artists like Jimmy DeSana, David Wonjarowicz, and Roger Cutforth, the second iteration of a two-part exhibition at Hal Bromm Gallery explores the multifaceted nature of the face

A portrait has the capacity to transcend time and space. It’s a means of understanding the complexities and intricacies of the person portrayed, of the artist behind the portrayal, of the atmosphere of a particular period. Renderings of faces should lean into that quality of multiplicity—the distinct perspectives that they capture.

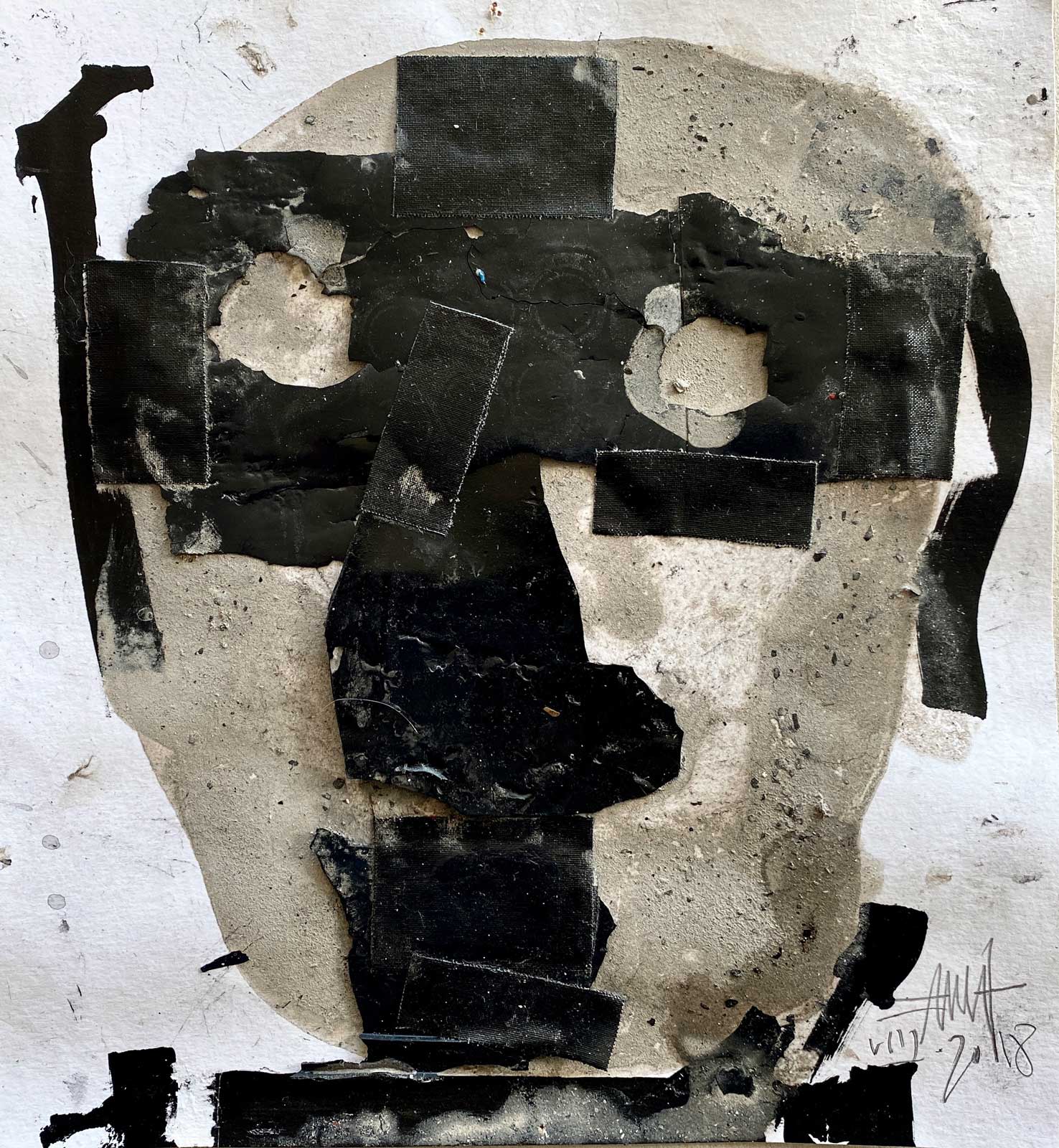

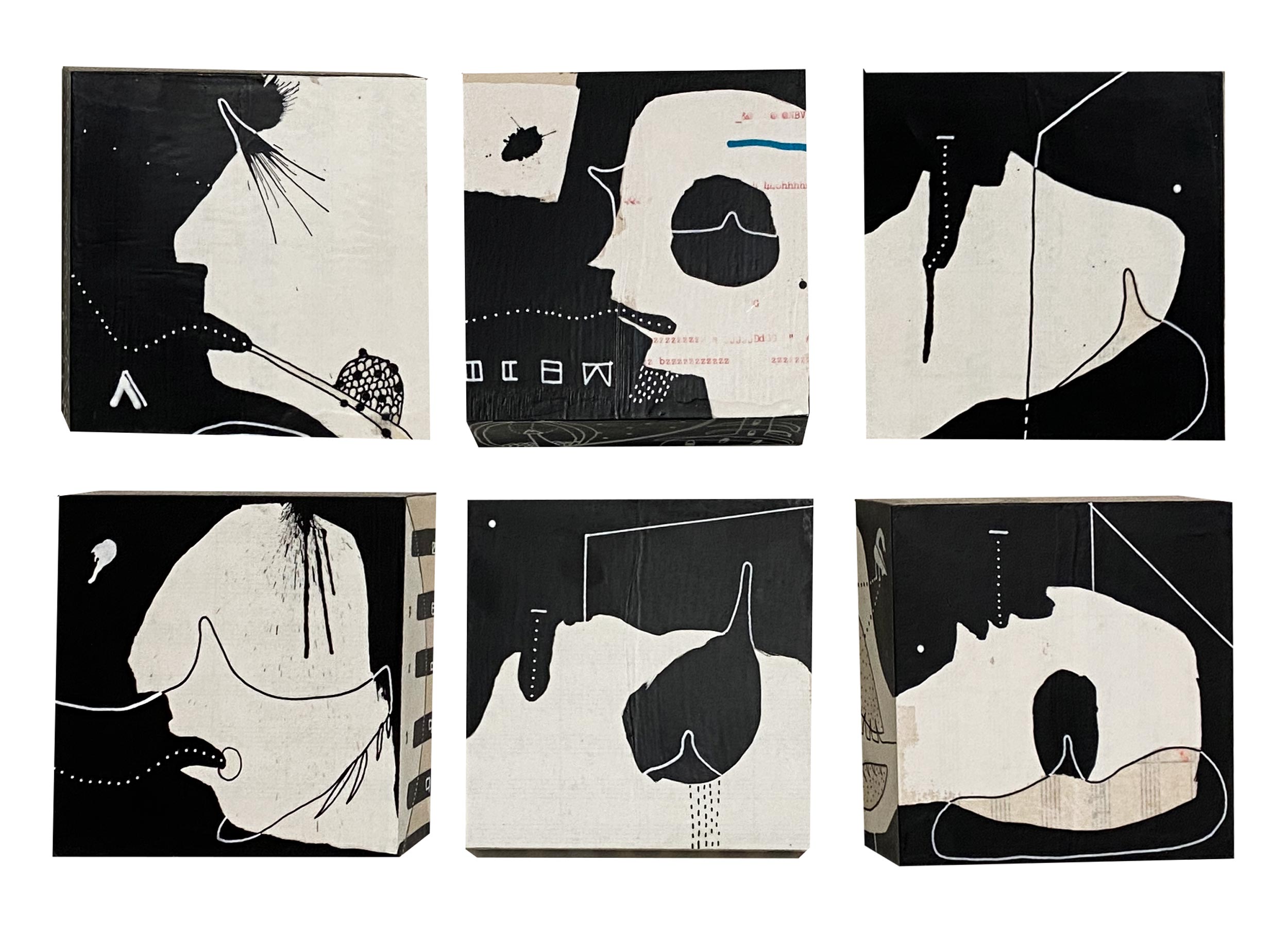

The second iteration of a two-part exhibition at Hal Bromm Gallery, FACES II features 30 works by artists across a range of mediums who challenge the singularity typical to portraiture in a classical context. Featuring artists like Jimmy DeSana, David Wojnarowicz, Tim Fite, Gary Schneider, Pamela Sneed, Roger Cutforth, Frédéric Amat, and Ted Rosenthal, the exhibition capitalizes on its gallery’s history, drawing on the relationships Bromm has been nurturing since the ’70s, when his space first earned a reputation for championing unexpected talent.

“Our face, and by extension, our self, is not only the face we see perfectly reproduced from one angle in a photograph,” Bromm muses. “It is every image of our face from every angle, it is every remembrance of our big ears or small nose, it is every first impression anyone will ever have of us. It is the unedited, unflinching, intimate knowledge of an imperfect, greasy pimply face.”

The gallerist joins Document to explore the multifaceted nature of the face, examining its history of representation in art, and the creatives who are expanding our understandings of it for the future.

Megan Hullander: Where does FACES II conceptually differ from FACES I?

Hal Bromm: FACES I and II are part of the same exhibition. There could have been hundreds of artists, as the subject is such rich terrain. Artists have always been fascinated by faces in any form; viewers are captivated by them.

Dividing the exhibition into two parts more comfortably accommodated the many great works selected. Yet, with any group installation, certain synergies and themes emerge. Perhaps FACES I opened the door for FACES II to more directly challenge archetypes of portraiture, and what it means to capture the essence of a person through portraying their face. In both, threads developed that dictated installation planning, as some ‘faces’ began to have clear dialogues with others. Both iterations built on that synergy.

Megan: What about portraiture specifically appealed to you, enough to center a show around it?

Hal: The face is universal in art—across place, time, medium, style. Throughout history, portraits have been an effective way to tell a story, and often provide a window into life at another time. The image of a face can capture the essence, psyche and spirit of someone, making it difficult to look away—perhaps projecting a viewer’s own life into the work, relating one’s own experiences to it. The special force that attracts us to faces becomes a central, unifying thread for a community of viewers and artists. And the near-universal familiarity results in portraiture being a uniquely accessible genre.

As the pandemic ebbed and then resurfaced, our ability to connect through such contact suffered. For many, seeing a masked face created a sense of loss. As masks come off, we see more of the person we missed. And today, faces seem to be the subject de rigueur—currently, front and center at Alex Katz’s popular exhibition at the Guggenheim, and curator Helen Molesworth’s fine exhibition at the International Center of Photography, Face to Face: Portraits of Artists by Tacita Dean, Brigitte Lacombe and Catherine Opie. The pandemic kept people away from each other, and our faces—seen on Zoom, in an Instagram post, or best of all, in person—are psychologically important to us.

Megan: What is it about classic portraiture that feels restrained to you? Why is it important to depart from that?

Hal: Is classic portraiture restrained? Perhaps the perception of restraint in classical portraiture speaks more to the setting in which the work was created, both temporal as well as geographic, and the social status of the subject. Formal portraiture was considered the only valid representation of the person, usually elaborately dressed and staged. As art has progressed from antiquity to present, societal norms and expectations have—generally—loosened, freeing artists to be more expressive with their work. This goes hand in hand with social justice and liberation movements throughout history, which are slowly allowing minoritized artists to take up more space. This departure from restraint might be seen as crucial to human progress, both within and outside of the ‘art world.’

Working within the confines of the ‘classical’ idiom, artists like John Singer Sargent broke free of convention with many of his portraits. His painting of Dr. Pozzi, depicted in a red dressing gown, broke new ground with its undertone of gay sexuality. And his scandalous 1884 portrait of ‘Madame X’ certainly challenged accepted standards. Fast forward to Warhol’s commissioned vanity portraits, where one sees the subject as the object of both admiration and scorn, self-obsessed with celebrity, and the notion of being seen as important within the cultural hierarchy of the day. Many of those faces meant—and still mean—a great deal to people, not just those who commissioned them.

Today, it might be argued that a Basquiat face is just as culturally significant as a formal royal portrait. Cultural constraints have shifted, so that a classic antique European portrait can be appreciated next to a Francis Bacon, side by side, without a need of rejecting one or the other. The exhibitions assert the value of creating art environments that take this for granted—that the scribble labeled ‘portrait’ and the ancient noble’s mask are both important; that they have something to say to each other, and that they benefit from the opportunity to say it.

“The face is not a single, perfect image, but a flowing thing, alive and pulsing in every moment with changes minute and exaggerated.”

Megan: How did you go about selecting artists for this show, and what narrative were you hoping to build from the pieces?

Hal: At the outset, the goal was to let the works create a narrative, rather than having to select artists or works that fit within set parameters. FACES avoided obvious choices and well-known artists in favor of younger and fresher faces, a gallery hallmark.

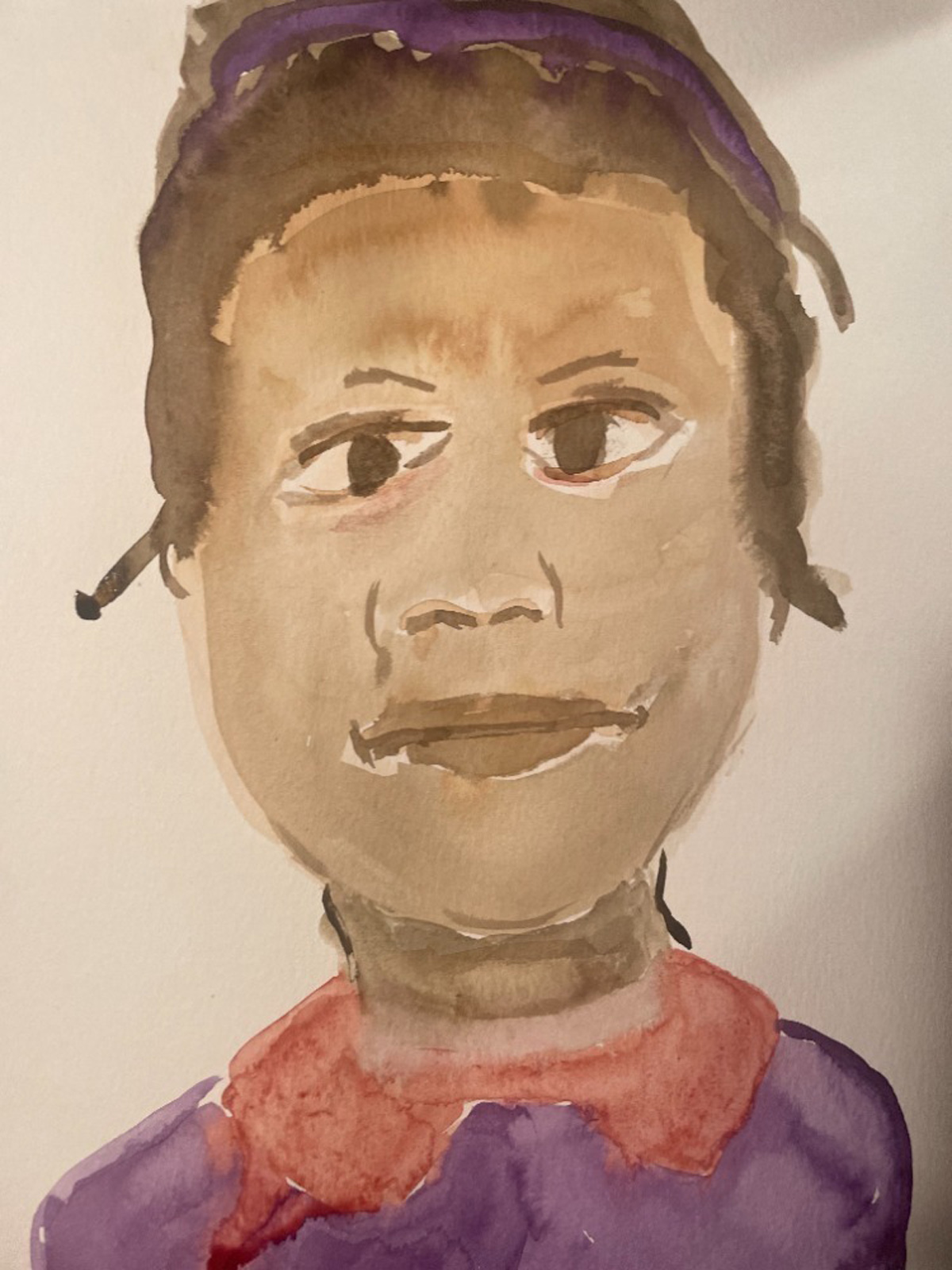

Artists whose work involves observation on the world around us—political commentary and personal struggle—are among those selected. Many faces in the exhibition challenge our perceptions and question the status quo. Simple but powerful portraits of murder victims become memorials to those killed at the hands of police in the recent watercolors of Pamela Sneed, while David Wojnarowicz’s work, showing him buried alive but for his face, recalls government indifference to the AIDS crisis; the artist died of AIDS within a year of its creation. Deborah Kass’s 2016 riff on Trump’s image, urging ‘Vote Hillary,’ harkens back to Warhol’s famous neon-tinged face of Nixon—a perk for donors to the McGovern campaign—championing support of that candidate. Ted Rosenthal’s Mussolini Flushing Himself Down The Toilet, rendered in steel plate and spray paint, packs a humorous punch.

Perhaps every work of art, as a reflection of its artist, functions as a self-portrait to some degree.

Megan: Has spending time with these experimentations on the portrait altered the way you experience people, or their faces, in your everyday life?

Hal: Faces are windows into our personalities, where feelings and actions come alive. Lucio Pozzi’s ink on paper works give us the living face, in motion and action. In his work, he reminds us that the face is not a single, perfect image, but a flowing thing, alive and pulsing in every moment with changes minute and exaggerated.

The nine faces in Tim Fite’s Final Breath, a group of wax and ink drawings on wood, seem to introduce a politically powerful display of how a face has been reduced and pummeled under the boots and blows of life. Perhaps it belongs to a victim of advanced capitalism: the face of a man seen as a worn-down tool, a cog in a great rusting machine that is nearing exhaustion under an iron hand.

Megan: Have any pieces in the show challenged the way you conceive yourself, or the way in which you present your individuality?

Hal: The works on view have not challenged how I conceive myself, but they underscore how perceptive artists can be in portraying the face—not necessarily challenging what one sees, but the manner in which it is seen.

Gary Schneider and Pamela Sneed’s works, in particular, have challenged the notion of perception. In Schneider’s work, one sees the importance and beauty of oils in the face, of blemishes—things that, in popular portrayals of the face, are ferreted out like plague. In Sneed’s pieces, we see the translation of outside perception and memory at work; over time, memory erodes faces, and reproduces previously insignificant details that somehow become central to the remembering. These mutated faces in our memory are just as real and significant as our ‘actual’ faces—those ‘realistic’ images of faces captured in photographs or classic portraits.

There is also the distance of outside perception. Seeing a face as a stranger, for the first time, the image our mind produces may as well be a caricature. Our face, and by extension, our self, is not only the face we see perfectly reproduced from one angle in a photograph. It is every image of our face from every angle, it is every remembrance of our big ears or small nose, it is every first impression anyone will ever have of us. It is the unedited, unflinching, intimate knowledge of an imperfect, greasy pimply face that only a lover could have.

FACES II is on view through March 31, 2023 at Hal Bromm Gallery in New York.