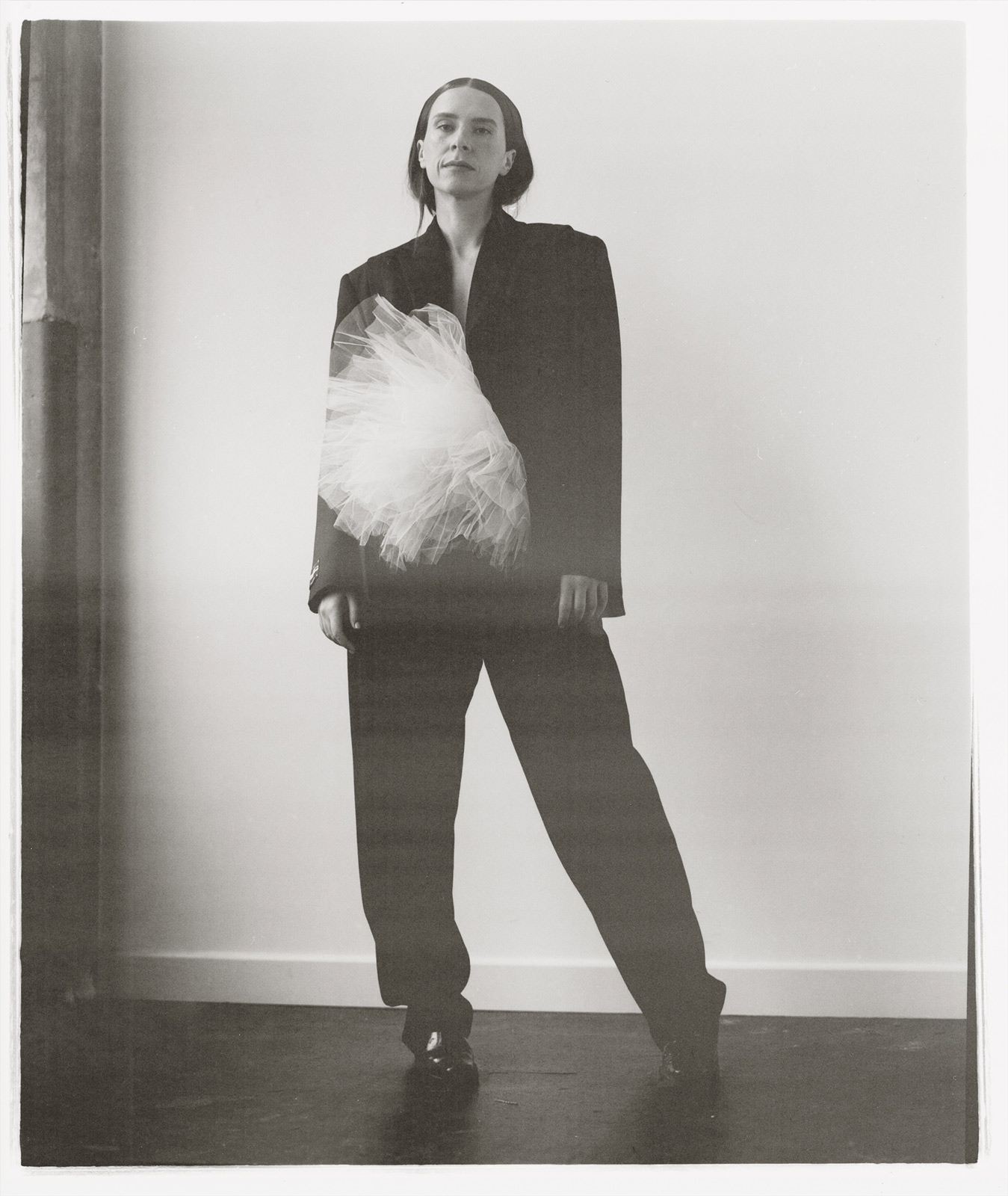

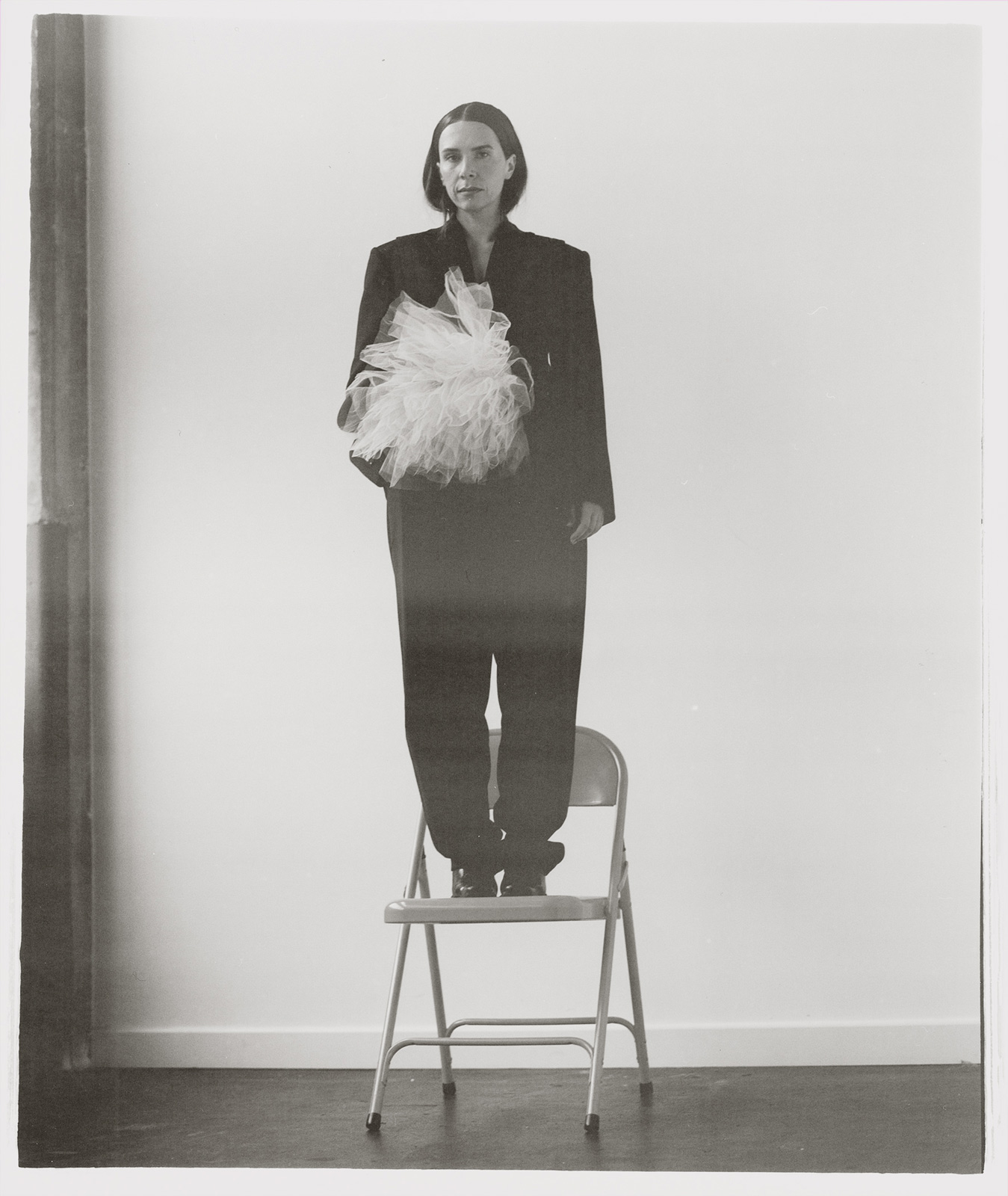

Document catches up with Ana Kirova, the radical platform’s founder, examining the roots, rules, and labels of the modern sexual landscape

In 2014, Feeld was born—the brainchild of Ana Kirova and Dimo Trifonov, a couple of London-based graphic designers looking to expand the bounds of their own union. It’s been called a hundred things: the hookup app for the emotionally mature; the Tinder of threesomes and swingers; the ultimate dating site for open-minded lovers. In any case, the app is an object of intrigue among singles and couples and triads and so on—really anyone seeking any sort of unconventional connection. Its mission shifts depending on who’s using it, making Feeld hard to pin down or sum up.

Kirova, the company’s recently-appointed CEO, says they were likely too early for their time: “We had to fight to explain what Feeld was about. We started when there weren’t really words for what we were trying to do.” In the mid-2010s, non-traditional relationship structures, and non-mainstream desires more broadly, were firmly situated under the private-life umbrella. Non-monogamy was relegated to shock-factor TV specials like Sister Wives, or automatically characterized as sex addiction or cheating; kinks were synonymous with promiscuity, and sex positivity, with hedonism.

Kirova and Trifonov got lucky, in the sense that they caught a cultural swing, creating space for what already existed on the fringes, and was starting to branch out—namely, curiosity around alternative sex and relationship models, and the active, ongoing pursuit of them. The latter was mostly relegated to the shadows: dark-room cruising initiated through word-of-mouth, apartment orgies, pay-to-play illicit sex clubs. It’s not that these routes have disappeared, or that apps like Feeld could or should replace them. But not everyone has the drive—or the sense of personal security—to do the work to find them. If there was that gap in Kirova’s own quest for self-expression, it had to exist for others, too.

“Feeld allows you to enter that space,” she says. “You don’t have to show yourself; you don’t have to say exactly who you are. You can look around and see what people say about themselves. Sometimes, that’s enough to make you feel a little more comfortable. That level of access is difficult to recreate in a physical environment.”

At first glance, Feeld isn’t too different from other popular dating apps. It’s a clean, simple interface: You choose a few nice photos, agonize over your bio, set your location, input your name and age. After that, it starts to diverge: You can join as a single person, or as a couple. The gender, sexuality, and desires options are expansive, so much so that a glossary has been fashioned for each drop-down menu. Demiromantic, and seeking someone to text? Homoflexible, looking to do bondage with FWBs? You’ll be able to say it right from the get-go, cutting out small talk and incompatible prospects.

“I think language is a very big part of what we do,” says Kirova, on that note. In its early days, Feeld had three gender options: Man, Woman, and Beyond. “I received a very considerate, but very emotional, message from a trans member of the community, who told me they felt erased,” she recalls. The conversation that ensued led to the development of Feeld’s wide vocabulary—undoubtedly, one of its biggest assets. The team now takes care to consult the community they seek to serve, constantly evolving their internal language to reflect the broad scope of users. In short, they’re trying to humanize the machine they offer.

But is that really possible? For Kirova, the venture started with design, going for warmth over start-up sterility. “Sex and sexuality generally had this slightly dodgy aesthetic,” she says. “If you put intent and beauty into it, how you interact with it changes.” It’s a concept we see elsewhere in the industry: A few years ago, for instance, there was that boom of audio porn, marketed largely toward women off-put by the graphic—or fake, or just unsightly—nature of the typical adult production; or, rather than doing away with visuals all-together, indie filmmakers gained traction for productions featuring finer cinematography. Beyond Feeld’s aesthetics, there was the overarching mission of collaborating with artists and writers. In Kirova’s view, “Tech bros were tech bros. We [needed] people from various backgrounds involved, from the very early days. That helped set the groundwork for appreciation and respect and curiosity.”

In that vein, she took inspiration from pre-existing art and literature—work that contends with sex and relationships, but isn’t, per se, defined by them. She references Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy, traversing themes of gender, race, consent, power, and hierarchy; there’s Brave New World, with its radical take on pleasure. The film Her was particularly formative: “Theodore, Joaquin Phoenix’s [role], decided to be with that AI, despite what it meant. There was discovery, for both characters, of what they wanted and what they weren’t getting. That level of awareness only comes after exploration, vulnerability, willingness to go out there and do something that you’re advised not to do.”

“Feeld is operating, all the same, in a politically-fraught moment. The sexual landscape is changing again, and bound to be met with appeals to morality, to tradition, to the regulation of bodies and of self-articulation.”

It’s an intriguing idea, viewing Feeld as a resource—equally valid whether it lands you a partner, or just teaches you something about yourself. The app is certainly a means of sex education, with all the transparency missing from health class, and, hopefully, less of the awkwardness. Kirova herself—who grew up in Bulgaria, with abstinence-based curricula and, luckily, a sex-positive mother—learns much to this day from the platform, reading their in-house blog; at the moment, its homepage features posts on dollification, subspace, and OPPs. (One Penis Policies. It’s safe to assume that most readers could glean something new, from at least one of these posts.) “A lot of things we put out are new to me,” she says. “It’s a treasure chest, feeding me all sorts of different experiences, worldviews—the nuances of everyone’s perceptions.”

It goes beyond picking up sexuality’s modern language, its labels and signals and acronyms. “What I hear,” says Kirova, “is that Feeld provides a sense of belonging, because of its shared code of conduct.” That is, if someone acts inappropriately—beyond intervention from the app’s administrators—other users are likely to call them out, acting on long-upheld codes from real-world kink communities. That’s not the work of Feeld itself, but testament to the space it creates: a digital home for the sexually marginalized, where a foregoing groundwork of care and respect seamlessly transfer over.

It all boils down to openness. Want to stay anonymous? Monogamous? Never leave your apartment? You’re within your rights. Same goes if you want to be tied up, or to tie someone up yourself. Every generation has its Sexual Revolution—and just as certainly, its own Sexual Panic: The Flappers spurred moral debates, around whether young women should be able smoke and drink and dance and party; the birth-control pill, on the purpose of sex in general; the free-love movement gave incentive to the religious right—scandalized by the pursuit of pleasure they saw all around them—shaping American conservatism into what it is right now.

Feeld is operating, all the same, in a politically-fraught moment. The sexual landscape is changing again, and bound to be met with appeals to morality, to tradition, to the regulation of bodies and of self-articulation. Kirova is creating space, then standing back and letting reformation unfold: “I’m working on a future where the default is [permissive of] the diverse ways we relate to each other, based on what people need, and what makes them feel whole—rather than subscribing to a made-up model that might not work for everyone. I see signs that this is where we’re heading to. [Feeld] is one thing, but when you’re trying to influence the fabric of society, the way that we do, the only way to do it is to tap into culture.”

Hair by Johanna Cree Brown at Gary Represents. Makeup by Gina Parr at W Lab.