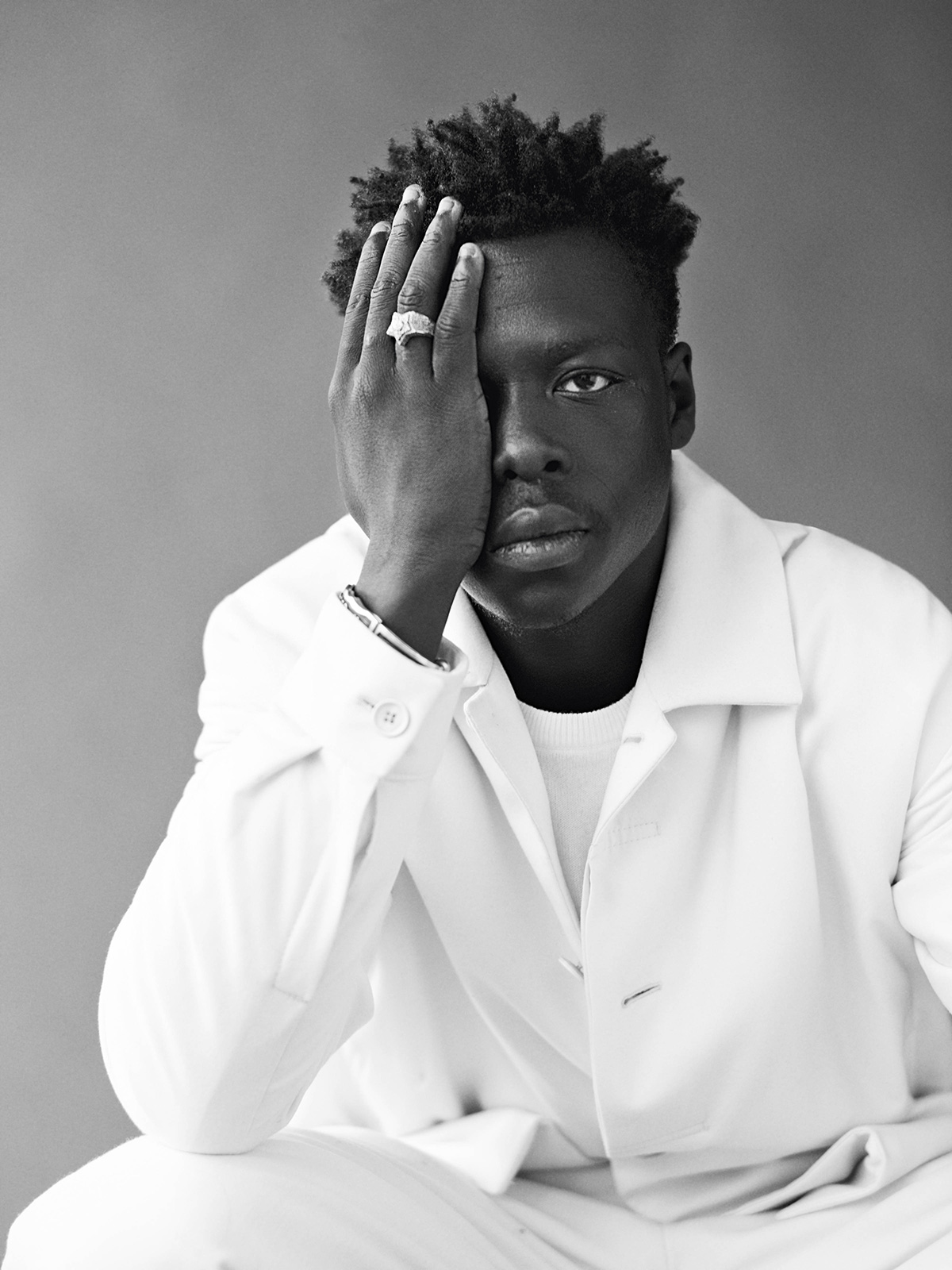

For Document’s Winter/Resort 2023 issue, the breakout musician reflects on his many lives, from the frontline to international fame

If art’s purpose is to chronicle life, Pa Salieu can give testament to living more than just one.

Born in Slough, an industrial town 20 miles west of London, the musician spent the majority of his early childhood in The Gambia. Until the age of seven, he stayed with his grandparents in Serekunda, the nation’s largest urban center—learning Wolof, running the streets, sharing a bedroom with his cousins. “My auntie would give me change and I’d hide it under my pillow,” he remembers, laughing. “I would never find it in the morning.” Behind the house was Salieu’s grandfather’s farm, where they grew corn and mangoes. His uncle’s Islamic school stood down the road, above a market he’d visit with friends in the evenings, collecting mint leaves scattered around the threshold by passing shoppers. The Gambia, he says, is where he learned community.

Once Salieu’s parents were settled in the UK, they sent for him. He moved to Hillfields, a suburb of Coventry with a reputation for crime that stretches all the way back to the blitz bombings of World War II—the city couldn’t bounce back, neither financially nor socially. Today’s residents refer to the stretch between Primrose Hill and King William Street, a span of blocks known as the town’s “frontline.” It served as the inspiration for Salieu’s breakout hit of the same name—part of his 2022 record Send Them to Coventry, the album title derived from a 17th-century English phrase relating to ostracization, as Royalist prisoners were often exiled to the then-outlying Parliamentary stronghold. The track, with its unforgettable, weighty hook (“They don’t know about the block life / Still doing mazza inna frontline”) quickly gained traction. On BBC Radio 1Xtra, it was the most-played song of 2020.

Coventry was a taste of “real life,” according to the artist. “There’s a lot of fiends. Cleaning up needles. Certain memories can’t escape me.” He started recording music soon after his best friend, Fidel “AP” Glasgow, was stabbed to death in a fight that Salieu was also involved with; and a couple of years ago, the artist himself survived a shooting that left 16 bullet fragments in his head and neck. “I’m not going to shut down,” he says. “Writing keeps me from losing my mind. Too many friends gone too young. But you don’t know who you’re pushing—future leaders, future kings, future queens. How many frontlines are people living?”

The chapter Salieu finds himself in now feels surreal. His videos are playing on MTV; he earned a gig on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon; he’s racking up millions of streams, performing at big-name festivals, heading fashion campaigns, and winning the hearts of critics everywhere. “I’m getting used to life right now,” he says. “It’s like a living movie.” A movie, in that Salieu is cutting from scene to scene quickly; it’s the hero’s journey for the modern age, with barely the space for a transformation montage along the way.

Speaking with Salieu is a bit like driving manual—learning to switch gears on the spot. Sometimes, he pauses liberally before answering a question. Others, he cuts in before the end of my sentence, eager to get his point across. He loves a tangent, but not as much as he loves apologizing for them: “There’s so many things in my head. It’s hard for me to focus on one. We’ll have another interview one day, and the articulation will be so, so, so much clearer.” And for all the stoicism, the toughness Salieu’s music portrays, he’s generous with his emotions—grinning, gritting his teeth, tearing up when speaking of his grandmother. “How can I be loved?” he wonders, when I ask what it’s like to be recognized on the streets of Coventry these days—how to recognize a fan, versus someone to steer clear of. “My past makes it very confusing for me.”

The thread through Salieu’s body of work may be his rock-solid sense of intention. He believes in fate—it’s what assured him he wouldn’t die in the wake of that 2020 drive-by—but even more so, he believes in personal responsibility. “I see myself as a bridge,” he says, maintaining that he was sent to The Gambia for a reason deeper than his mother’s struggles as an immigrant. He’s on a mission: “It’s what was written for me to see. Two different worlds. As a human being, I think I was made to make a change.”

What form that change might take isn’t set in stone, but Salieu has plenty of ideas. Just recently, he returned to The Gambia for the first time in 18 years. Save for his grandparents’ absence, everything—from the house he grew up in to the city’s storefronts—seemed the same. “I was a child again. However good that made me feel…” He trails off. I ask Salieu whether the trip brought him closure: “It was an opener! All I know is action.”

“It’s what was written for me to see. Two different worlds. As a human being, I think I was made to make a change.”

What soon followed was Salieu’s most animated response yet: He wants to refurbish Gambian lorries, turning them into mobile schools equipped with eight seats and a set of computers. Or, he’ll build a school for the arts. Practical skills could be rendered more accessible, too: “Teaching someone how to farm. How to build a well. How to do architecture, instead of using their power to overtake someone else. I didn’t have school like that. I was in the exclusion rooms. All my life, I’m thinking, ‘I could create. Give me a paintbrush!’”

While Salieu’s beats align with the stylings of contemporary UK rap—drum-forward, synth-heavy, and dark—with a few creative incorporations of old-school instrumentation, it’s his vocals that set him apart. He transitions easily from sharp enunciation, to modulated half-singing, to straightforward, charismatic speech. He understands rhythm intuitively, never backing down from intricate production; details that might get muddied in another artist’s music only add to the richness of Salieu’s soundscape.

If you google the artist’s name, you’ll find him grouped in with a handful of genres: Afrobeats, drill, grime, dancehall. His own allegiances, however, might surprise you: “I can’t be called a rapper. My tribe back home—we’re folk singers.”

Folk was Salieu’s introduction to music, by way of his auntie Chuche Njie—a renowned artist of the genre who he sampled on Send Them to Coventry’s “B***K.” “The way she sings is exactly the way women would sing next to the king,” he maintains. “Explaining the past vocally, beautifully. The definition of folk singing is to carry on the past.” His grandmother helped to instill this value, as well, gathering Salieu and his cousins each night, telling them stories, feeding them fragments of their collective history—a history, it should be understood, that Salieu is a living, breathing extension of. “I’m stuck in the past, trying to walk towards the future,” he says. “I’m going to explain my life, spread my love. My job is to carry on this pride.”

Understanding Salieu’s music as an extension of the folk tradition sheds new light on his lyrics. In “More Paper,” on the surface level, he’s mourning his friend: “When my brotha died, I swear I lost myself / I blame myself, I never saw who killed AP.” Taken universally, though, he’s speaking to the mundane ties between grief and guilt—attesting to the all-too-common experience of early loss in a neighborhood like Hillfields, archiving a life and a death in the process. “Energy” is in the same vein: “Some do it for the livin’, most do it for clout / Some do it for the money, the dollar, the pound.” Here, Salieu gives prominence to the societal factors that provoke crime and violence—decentering morality and taking control of his own culture’s narrative, rather than leaving it up to the assumptions of outsiders.

It all boils down to Salieu’s ego. His stubbornness. His empathy—for himself as much as others. The artist speaks of the figure of the “Afrikan Rebel,” his 2021 EP’s namesake: “You’ve heard of Pangea—you know, where everything starts. We’re from the dust. We’re from the sands. Whatever madness is given to the Afrikan Rebel, you still wake up in the morning and move, move, move.”

Salieu remembers being 18, learning about the pyramids in Sudan for the first time: “I feel a sense of pride, right? There’s beauty to carry on. My job is to carry on beauty. If I have to sacrifice myself for this—for another me that’s going through hell—so be it. I want everything documented. I’m the blueprint for someone else.”