In their latest performance piece, the dancers employ a simple set for narrative flexibility, communicating a range of characters and places through their movement

Baye & Asa move with violent grace. The harmony of their performance implies an impenetrable synchronicity of thought—one that supersedes the fallacies of human relationships. That apparent sameness is underscored by the breadth of their relationship, which traces back to a first-grade dance class. But it’s those fallacies upon which the poignancy of their performance is built. Arguments, they explain, are often the genesis of their art. The passion that permeates their conflicting opinions is what signals to Baye & Asa that a topic is worthy of artistic exploration—worthy of an audience.

A lot of artists are afraid to make “COVID art.” There was a certain safety to it when the genre first emerged—a sturdy socio-political bubble that protected it from any real critique. But as flooding Instagram stories with fliers for protests and fundraisers went out of fashion, that bubble became increasingly delicate, and eventually inverted. To make art stemming from the pandemic was labeled easy, obvious—even desperate. At this point, however, the ideas at the foundation of (good) COVID art were only at their formative stages. What was bubbling then is just now beginning to erupt, nudging that temporary attention into something longer-standing. Baye & Asa’s HotHouse is one such work.

The choreography duo built the structure and thematics of their most recent project from the universal sense of isolation and the spotlighting of societal and institutional failures that defined the pandemic’s earliest months. But their work is informed by that influence—not defined by it. Their interrogation of distinctly American ideologies probes at that which permeates through even the most earnest-minded’s subconscious—at the myths wedged deep into the national consciousness.

Inside a rectangular plexiglass frame, a floor made of dirt is illuminated with a lighting display that fluctuates with more emotional range than some people are even capable of. Set to a live score from Show Me The Body’s Julian Pratt and Harlan Steed, HotHouse sees Baye & Asa adopt a series of characters in a range of imagined settings, threaded together by a sense of confinement and a unique psychophysical vocabulary.

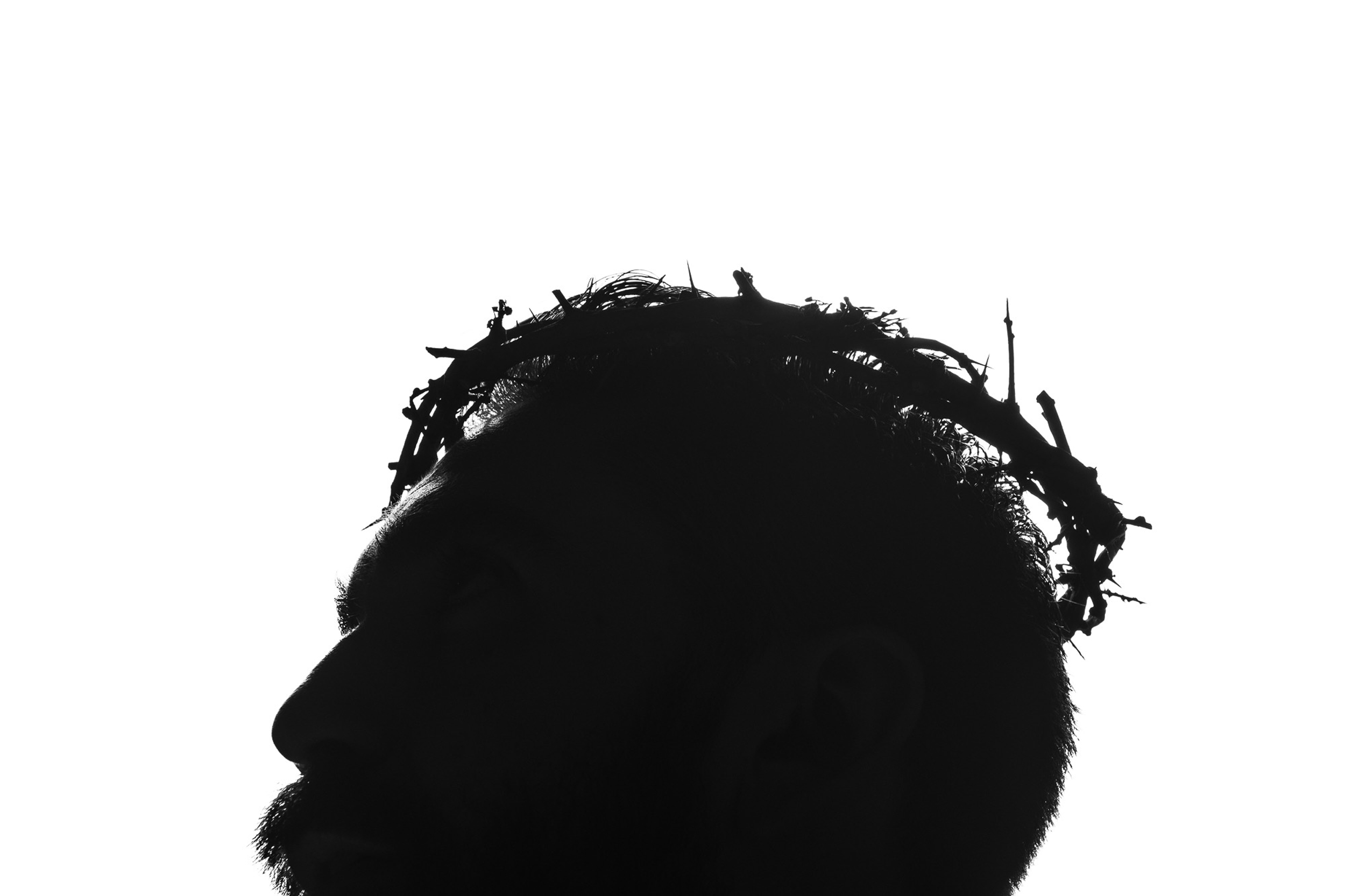

Following its premiere at Red Hook’s Pioneer Works, the duo joins Document to discuss the conceptualization of HotHouse, the narrative adaptability of simplicity, and the myth of “white Jesus.”

Megan Hullander: Where did the concept for HotHouse originate?

Amadi ‘Baye’ Washington: The top of the pandemic really brought us together, and we had to figure out a way to make live performance happen, despite the need to physically separate. The idea for HotHouse started as a response to the epidemiological necessity for physical separation—which is why it takes place inside of a box that separates us from the audience, through plexiglass and wooden studs.

Sam ‘Asa’ Pratt: It was essentially like, How do we innovate the geometry of live performance, instead of waiting for houses to reopen? We were thinking outdoors, of all of the ways in which I’m sure many performance artists were thinking about ways to make their art happen. But the response to George Floyd’s murder grew, and the cultural conversation started to shift. I think the line that we’ve written is, ‘COVID-19 unmasked the greater systemic failures of America.’ We, for the first time, understood—culturally, medically, in terms of housing—how communities are siloed. The pandemic underscored and gave new meaning to the ways in which we critique American society and politics.

Amadi: There was an equalizing factor to the pandemic that gave people a lot of space to reflect and be like, Whoa, the world is messed up. And maybe it always has been—but we were able to see, in a very up-close and personal way—that our social safety nets are much more fragile than we might have thought they were, even for those who are in more privileged classes.

Sam: Amadi talks about equalizing, which I think, from a virologist standpoint, is true—beyond the people who have autoimmune things, who are more susceptible. During the pandemic, people weren’t dying because of the disease. People were dying because there wasn’t enough staff at hospitals. That’s not related to COVID-19, but instead, this greater failure and inequity that exists structurally.

Megan: How does that concept of equalizing inform the way that you approach the relationship between yourselves and the audience?

Sam: There’s a divide. Like, we’re equal in the sense of we’re in the same space. But there is a clear divide. We’re locked in a space and the audience is free to roam—free to change their position throughout the performance and walk around this structure, 360 degrees. I think there’s a fundamental acknowledgment of confinement in the geometry of the performance.

Amadi: I will say, in terms of equalizing: We all see performances, and we all see art. And the first thing we try to do is find a narrative, or find ourselves within the work. And we’re talking a lot about the pandemic right now. But the piece is not just about the pandemic. I think being inside of a box, being enclosed in a space where there are only two people who are going through a journey—that is sometimes a little bit friendly and tender, but at other times anxious and aggressive—will create its own sense of equality. Or it will break that wall, that barrier that we’ve created between ourselves and the audience, because we’ve all spent a lot of time in isolation in the last few years.

“Dance serves us where language can be limiting.”

Megan: Given the change in context since this project’s ideation, has the function of the plexiglass expanded?

Amadi: People won’t be wearing masks, like we originally thought they would.

Sam: We imagined the audience in masks, and it was this beautiful image that compounded the theatricality of the work and the dangerousness of performing live during the pandemic. But now, we don’t want it to be a pandemic piece. Suddenly, a plexiglass enclosure becomes a sweatshop, a prison, a home, a building. There are all of these ways in which the structure, hopefully, is a narratively adaptable canvas in its simplicity.

Megan: What do you think movement brings to storytelling that might not be captured with other mediums?

Amadi: Dance has the unique capability to liberate thought into indeterminacy. How we perform—the physicality, the gaze towards another person—tells so much. As Sam was saying, it’s a prison cell, it’s a medical isolation unit. It can be all of these things, because we’re not telling the audience what it is. It allows the mind to go in all sorts of directions.

Sam: The ambiguity that exists in dance, because of its poetic nature, feels like a strength to us. It allows more people in. Dance serves us where language can be limiting.

Megan: What’s your process for developing characters, and how do you go about building them, defining them, and figuring out how to best embody them?

Sam: There are two of us. So, everything is always in relation to the other person—even if you’re doing a solo, their absence is part of the commentary. We are hoping to embody archetypes we see in American life, but then we are also very much ourselves. There are some dancers and dance companies who want to be gods and larger-than-life and technical beings, as opposed to real people. We often talk, in our physicality, about the virtuosity of pedestrian performance. How it can change the experience of a high leg into, like, this is happening to somebody—not a dancer executing a move, but creating meaning in space, because it’s a real person.

Amadi: We often start with a piece of primary source material, whether that be a film or a document, or something that is generally happening in the world that we can go out and research. Or we start from a set idea or a lighting image that we had and build from there, versus going into the studio and making some movement. When you think about a primary source material, it gives you the characters. Character development is embedded in the way that we approach choreography. I hope we get to a point where we can be researching movement, and just be in the studio like, Okay, what do we want to make next? Is this going to turn into a piece? But a lot of the time we’re in the space; we are oriented towards making something that feels like it is meaningful in relation to us as people. That’s why one of the first things I said was, I’m a Black man, he’s a white man. [That’s] never removed from the context of the work that we make. Even if we tried to remove it, it’s still gonna be a part of it.

“We often talk, in our physicality, about the virtuosity of pedestrian performance. How it can change the experience of a high leg into, like, this is happening to somebody—not a dancer executing a move, but creating meaning in space, because it’s a real person.”

Megan: The press release mentioned that you are trying to contemporize allegorical materials. What were those references for HotHouse?

Sam: There are a lot of ways to think about that. I think the most obvious one is the myth of ‘white Jesus.’ That feels, to us, like the very first delusion—that all of the world came from white people and an idyllic garden. That’s like the first lie of culture—that this dude was Aryan. It’s just historically and factually ridiculous. It feels like the myth of white superiority, the myth of white intellectualism, the myth of white high culture are embedded in the ways that we see ourselves problematizing contemporary American culture. It feels like it not only exists in this grand scale that I’m speaking about, but also in the more mundane ways in which people felt excited, happy, fulfilled, and satiated with their involvement in the George Floyd protests—in the way that people clapped at 7 p.m. I’m not trying to be judgmental about any of those things. All of them have positive aspects. But I think it’s a part of the narrative that starts with something like the myth of ‘white Jesus.’

Amadi: Towards the beginning of the pandemic, we were given access to a vacant bank and did a series called The Myth Series. We looked at a lot of ancient myths, and then portrayed them as we see them. Like, the myth of law and order—like law and order as a way to subjugate and oppress people, perpetrating modern slavery. So that, in its own way, is an allegory, a myth—that you can have law and order. And you see that around the world. But, from our own lens, we speak about the city that we’re from: New York, and the United States. Entitlement comes from the idea that you are ordained by this godly creature to take over the world. And that everything you do to serve other people is a sacrifice.

Megan: I think a lot of people—in the past few years especially—have been grappling with what constitutes performative activism versus action that’s actually valuable, and grappling with where and how much intention matters. It feels like that ideological struggle has been magnified for a lot of artists, and there’s newfound pressure on them to be activists in their practices. Does this feel warranted to you?

Sam: Sometimes we get labeled as ‘activist artists,’ and we push against it. We say we are political art-makers, not activists—and there’s a real difference between those things. I truly believe that artists do not have an obligation to fucking anybody, zero fucking people. I personally feel the desire to do this. And this is how I want to speak. And it’s how I’m interested in engaging with art and my mind. And so this is what comes out. But under no circumstances do I think that other artists have any obligation.

Amadi: Being an activist is something that has actionable steps, that lead to real outcomes. Just because I say something is about a political idea does not, therefore, make it activism. We can have this conversation right now, which is good, but it’s not activism. It’s starting a conversation, starting a dialogue. And sometimes starting that dialogue is the seed of activism. I hope that people walk away from this performance and think about what we were trying to say, or find their own space for discovery and commentary within themselves. And maybe that moves towards something that’s actionable—but maybe not.

Sam: Our culture likes to put politics on top of art, where it’s sometimes conflated with an artist’s identity. And just because an artist has a specific identity, people are like, It must be about this. No! I’m just making my shit. And maybe this abstract painting I made has nothing to do with that. I don’t want to be forced, because of my identity, to make shit about it.

Megan: I like that characterization—of art as thought or dialogue starter. How do the dialogues you attempt to generate in your performances inform those of your own for future projects?

Amadi: As we continue to make work, we start to see overlapping themes—one thing that we talk about a lot is white delusion—this idea that white people are ‘under attack.’

Sam: And, historically, it repeats itself over and over.

Amadi: That feeling that you are under attack is also what begets violence. If you’re in a position of power, and then you feel like you’re under attack, the fact that you have that power makes your violence even more possible, and even more palpable. We made this film called Second Seed that was in response to DW Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. The whole film is about a white race in danger. And therefore, like, we need the KKK, the white knights to save us from this free Black population. The delusion that existed back then still exists.

Sam: My favorite thing about our collaboration is that we’ve known each other since we were in first grade, so we can fight about stuff. Us fighting about things and disagreeing about politics is where the ideas grow, and they often come when we’re in the studio warming up, and we get heated about some shit. And then it turns into, like, Oh, this is something we really care about. And then it transforms. Our arguments often lead us to the next thing.