From Wilhelm von Gloeden to Oscar Wilde, the series hides a secret in plain sight: the untold history of Sicily’s gay destination Taormina

Luxury and lust populated Taormina long before Mike White’s gluttonous cast arrived on its shores. This season of The White Lotus echoes the characteristics that have defined the tourist town since the 19th century: sin, sex, secrets, scandal, seduction. The HBO series achieved a plot that embodies the drama of lovelorn period pieces, but is embroiled with the sort of discomfort usually reserved for the realities of romance. Each character is adorned with their own sex-soaked situational strife, from infidelity to unfulfilled desire—their resolutions all pinned to the idyllic promise of the Italian coast.

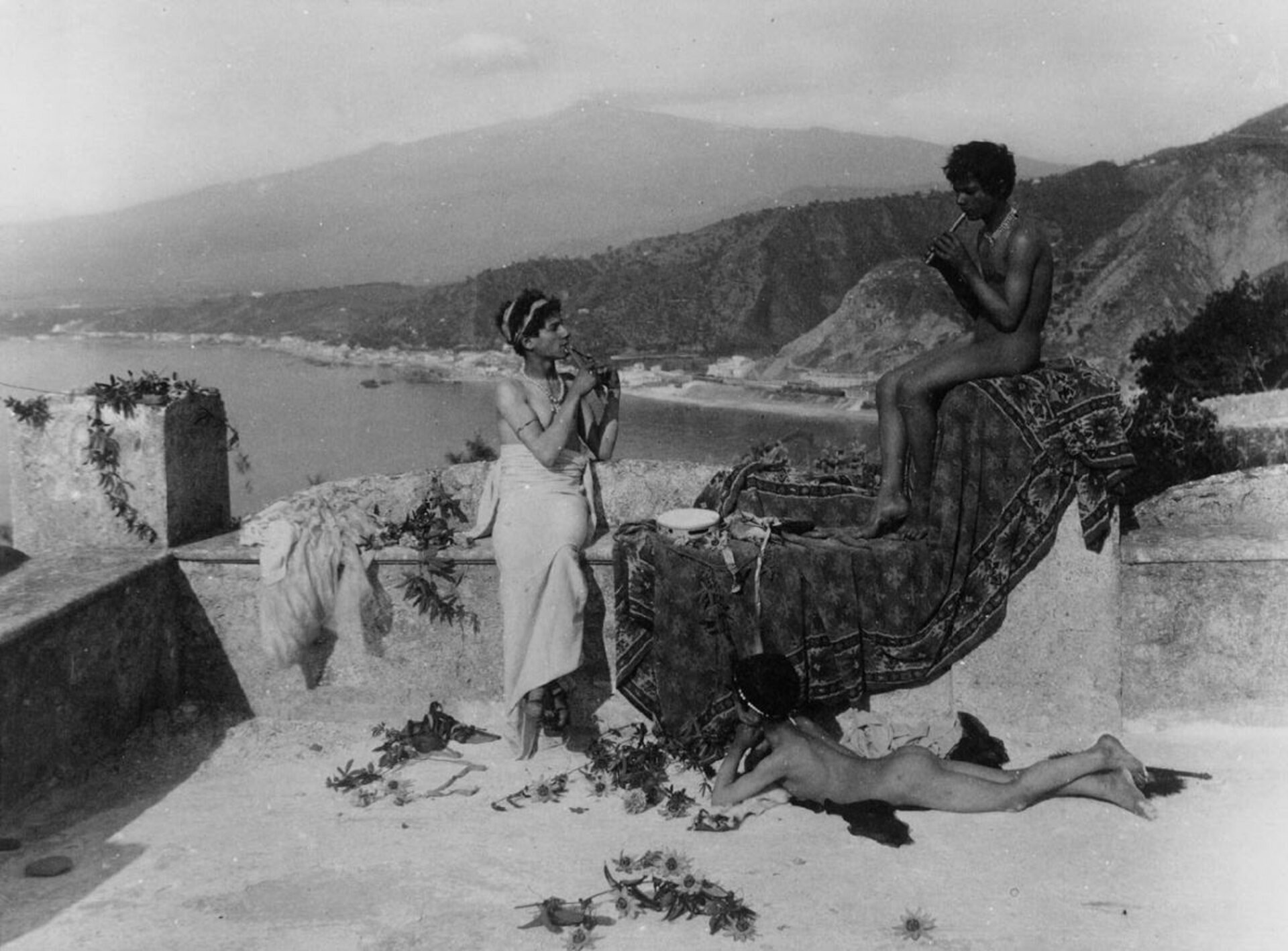

The show’s primary setting, Taormina, was one of the world’s first gay getaways; the sexual freedom it offered was made only more alluring by Sicily’s Arcadian climate and mythical mystique. German baron Wilhelm von Gloeden’s painterly images of queer youths, taken between 1878 and 1914, liken them to pagan gods, underpinning the city’s appeal. Says writer Leonardo Sciascia of the photographer’s subjects, “In the eyes of each of them, there was a light of savage distrust that contradicted the positions of their abandonment. Perhaps the baron would have loved a look full of love in them; but it was impossible to achieve this result with those children of Sicilian peasants and fishermen seeing themselves reduced to the object of an incomprehensible caprice or of an understandable and alarming lust.”

It was that lust that called to Oscar Wilde—who stuffed his suitcase with pictures of the “marvellous boys” in Taormina—and later, to those women worshipped by queer communities: Joan Crawford, Elizabeth Taylor, and now, Jennifer Coolidge. The White Lotus is defined by its subversion of expectations, and its second iteration of the show does that perhaps most elaborately in its inversion of the male gaze.

Its female cast is distinctive, each woman revealing layers of complexity over the course of the season: Daphne (Meghann Fahy) isn’t ignorant, but a master manipulator; Valentina (Sabrina Impacciatore) isn’t just a power-hungry bitch, but also a middle-aged woman still grappling with her sexuality; and Tanya (Coolidge) may have more intuition than we ever thought her capable of. It’s the series’s men that remain stagnant. Cameron (Theo James) turns out to be exactly who we thought he was: a hypermasculine fuckboy seeking dominance above all else. In the (sort of) same spirit as the tantalizing allure of the show’s so-called crazy women, Ethan (Will Sharpe) becomes more toxic as he becomes more seductive (see: the wet t-shirt that clings to his body as he stomps to shore, after his failed attempt to drown Cameron). Still, he never manages to deliver nuance. The men of the DiMarco family, who each embody a different generation of masculinity, are offered sprinklings of hope—all of which is revoked in the finale as they, in near-perfect synchronization, ogle a young woman at the airport. And the gays remain just “the gays,” even in their surprisingly villainous tirades. The most developed male character might just be Tanya’s husband, Greg, who doesn’t even appear in the majority of the season’s episodes.

The men of The White Lotus are eye candy, plot fillers, and foils, used almost entirely to construct the stories of its women. These women are sexualized, to an extent—subject to nudity, defined in part by their relationships to men, and portrayed by distinctly attractive actors. But they aren’t limited to their sexuality. (Sexual appeal, uncoincidentally, might be the only redeeming quality of some of its men.) Each of the series’s details further complicates its picture of femininity, even in the way that the women are dressed. Portia (Haley Lu Richardson) meanders between Urban Outfitters’s womenswear and stereotypically masculine styles—less a reflection of her ability to play with gender than an inability to find an identity of her own. As Harper (Aubrey Plaza) breaks from her character’s rigidity, so too do her clothes, as she aesthetically sheds an Audrey Hepburn-esque elegance in favor of the effeminate nature of Daphne.

The show’s cast is best classified as an ensemble—the women its primary characters, the men secondary. But if you were to assign it a main character, Coolidge’s Tanya is certainly your best bet. She’s Monica Vitti, she’s Peppa Pig, she’s Apollonia Vitelli, she’s Madame Butterfly. Despite their intentions, the gaggle of gays that flock around her only reinforces the aura of queerness emboldening her character.

That very aura of queerness really underscores the show’s entirety—after all, it was the gays of the 1800s who built the extravagance of Sicily, even beyond Taormina. (In Palermo, Tom Hollander’s Quentin namechecks Gore Vidal as a past houseguest.) Maybe it was just me (it wasn’t), but I expected to see at least some same-gender swinging from the couples on vacation—tensions between Ethan and Cameron broiling over into something more, or a playful moment of rebellion between Harper and Daphne during their overnight getaway. Most substantial, though, is the subversive promise of ascendency the gays once built in Taormina, which is mirrored by The White Lotus’s women. Lucia (Simona Tabasco) and Mia (Beatrice Grannò) successfully scam their way into what they want. Daphne, yet again, gets the final play in the quiet game she plays with Cameron. Portia is left with financial hope (perhaps a piece of Tanya’s pie, or as the next in line to monetize Albie’s affections). Harper finally gets laid. Valentina is liberated. And even though she ultimately fell, Tanya went out guns blazing.