Available digitally to the public today, Hauser & Wirth Institute’s catalouge raisonné premiers rarely-seen or exhibited works from the final decade of the artist’s life

“To think of ways of disorganizing can be a form of organization,” the American expressionist Franz Kline once said. His paintings wear a type of passion often associated with impulse, but his practice was deeply methodical, each work undergoing a series of studies with delicate revisions. Kline’s work stands in contrast to that of action painters like Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, and Willem de Kooning; his large-scale black-and-white pieces almost act as a bridge between his New York School contemporaries, and the progression toward minimalism that followed them.

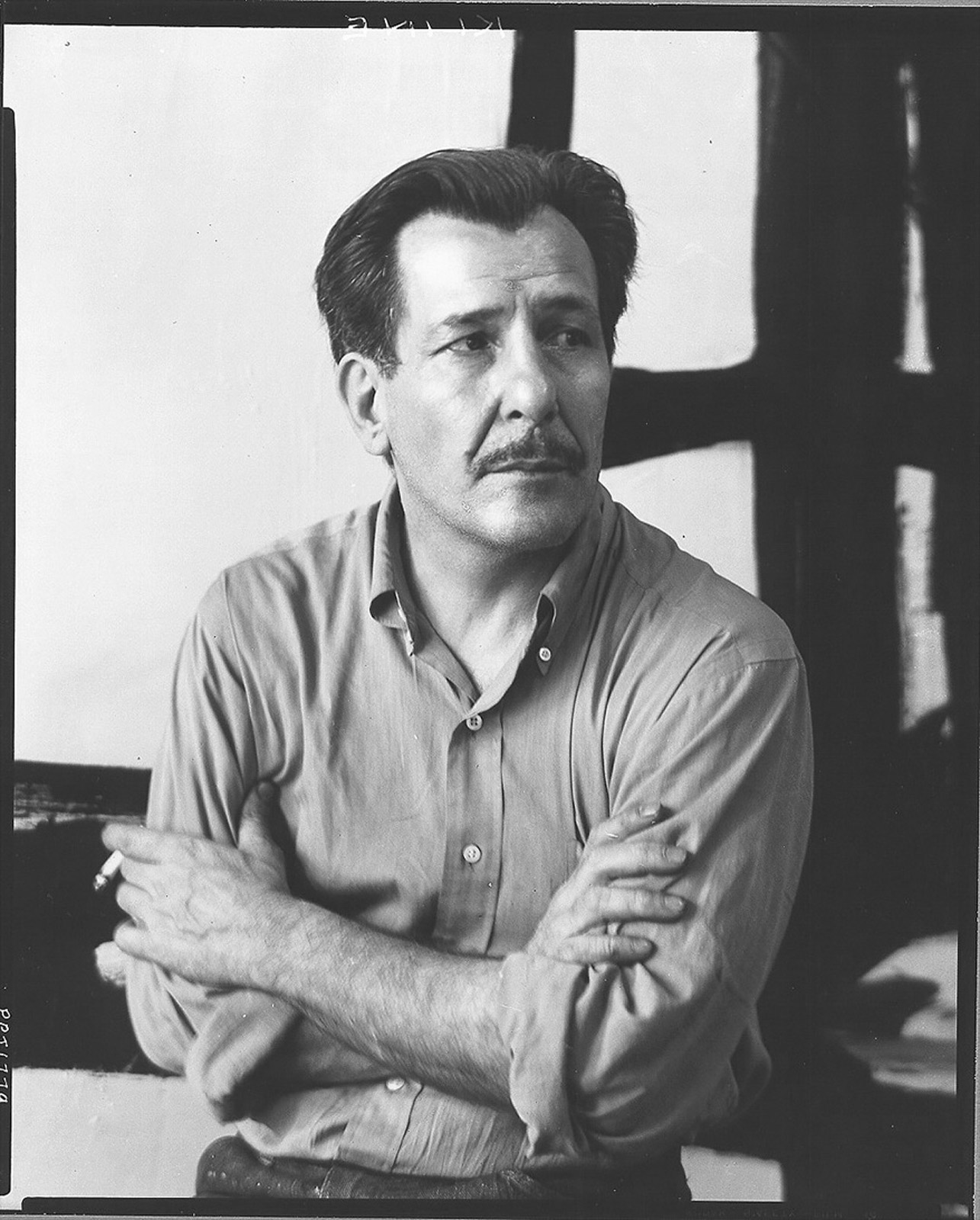

Under the direction of Kline scholar Dr. Robert S. Mattison, Hauser & Wirth Institute is publishing a new catalouge raisonné, Franz Kline Paintings, 1950–1962, which includes 256 paintings, many rarely seen or exhibited, created in the years before his death. As of today, the selection is available digitally for public consumption. The digitizing process extended beyond his art into a wider range of archival materials, such as Kline’s correspondences, exhibition files, photographs, artifacts, interviews, and books from his library, all compiled by Elisabeth Zogbaum, his close friend and executor of his estate.

Near his death, Kline felt limited by that which made his work revolutionary—defined by the monochromatic, broad brush strokes that critics claimed carried an objective opacity and frankness, which set him apart from the ambiguity and subjectivity of his peers. Though the color play he imagined as the next stage of his practice never came to be, a few works offer an idea of what it may have become—like the brown underpainting in Nijinsky (1950) and the traces of glowing green in Leda (1950). Perhaps it was best left unrealized, the stark nature of his black-and-white works found a perfect balance between subjectivity and objectivity, both enigmatic and obvious at once. Writes art historian Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, “His art both suggests and denies significance and meaning.”