In the wake of Bad Binch TongTong’s mesmerizing presentation, the Wuhan-born, New York-based designer joins Document to discuss his boundary-pushing anthropomorphic designs

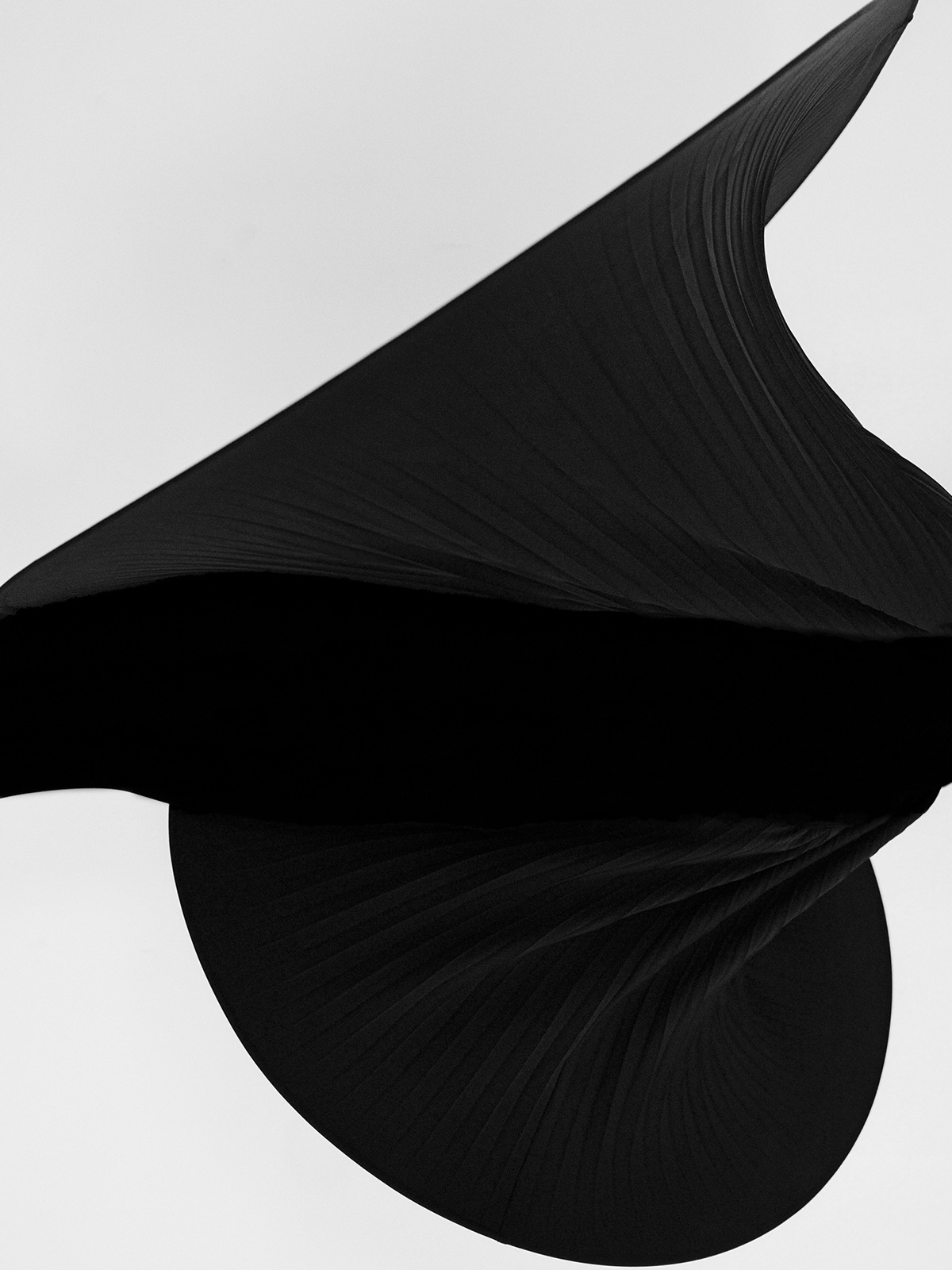

A torso spurts out eight limbs; another grows a pair of butterfly-like wings; a group of them are subsumed by a vertical stack of geometric buttresses, resembling an imposing, alien edifice more than any sort of recognizable physique. When the human body transforms into an anthropomorphic entity, its inhuman form compels the viewer to grapple with reality with childlike curiosity.

Wuhan-born, New York-based designer Terrence Zhou routinely inhabits this space of anatomical anomaly. This was more apparent than ever in his New York Fashion Week debut with his label, Bad Binch TongTong, created in collaboration with Stefanie Nelson, the choreographer and artistic director of her eponymous contemporary dance ensemble. During the presentation, bands of performers paraded down the runway, in no concise formation. The definition of choreography—the art of symbolically representing dancing—was interpreted formally as a group of shapes that chase each other away and compound together. Zhou’s designs seem to cheekily ask, Are these dancers in costumes—are these people? It’s clear that this is a dance about making a dance, a fairytale about a myth. As Susan Sontag puts it, “Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a ‘lamp’; not a woman, but a ‘woman’.”

As a designer, Zhou pushes the envelope so far—into incredulous, hulking convex and concave spheroids—that you cannot look away. Diving into hobbies and instincts, the designer sits down with Document to highlight his uncompromising design practice and its underlying sentiments, proving that the most abstract can also be the most emotional and epigrammatic.

“I design by asking the question, if we are fascinated by how the body moves, why can’t we translate these languages in visual formats that people are familiar with?”

Yuki Xu: How has your foundation in dance influenced your design intuitions? Do movements inspire you more than, say, textures or drapes?

Terrence Zhou: Aside from its technicalities, what I have learned are the dynamics between the partners, and the tensions of our bodies, through which we can express our emotions. I also see fashion as a medium to express our identities and emotions. In a way, every artistic format, no matter dance or visual arts, is similar to another and shares a solitary goal: to leave an impact on the audience. I started asking the question, if we are fascinated by how the body moves, why can’t we translate these languages in visual formats that people are familiar with?

Yuki: How did you first meet Stefanie Nelson, the choreographer who you worked with for your New York Fashion Week debut? What were some of the first conversations that you two had that eventually led to this collaboration?

Terrence: A stylist friend introduced us and pitched the idea of collaboration, and I felt a great synergy. I decided to have a show and reached out to her about the collaboration on my debut in New York Fashion Week. During the rehearsal, I realized that my gut feeling was right. There were just a lot of similarities in our artistic philosophies and visions. In a way, we complemented each other in a totally different yet similar world.

Yuki: What are some of the challenges of bringing a performanced-based, non-traditional, sometimes entirely abstract presentation into a New York Fashion Week show space, in front of a crowd of market-driven buyers and editors?

Terrence: When I decided to have a show, there was only me and my spectators. I did not care if they were buyers or market-driven editors. Being market-driven does not immediately mean that they would be against an emotionally touching performance. My goal is to provide a totally new experience in fashion through multi-sensory silhouettes, the likes of which my spectators have never experienced before. In addition, the presentation format has nothing to do with whether the designs can be appreciated and sold in the market. People will buy my designs because of the value people believe they have, rather than if the buyers like them or not. At the end of the day, it is the designers who can decide and educate the world on what fashion is.

“In my world, mermaids always exist. It is more of an inquiry to the world or dimension I have never been.”

Yuki: When looking at your designs, some are purely geometric shapes, while others are very conspicuous: butterflies, spiders, octopi. How do you approach the question of representation, or non-representation?

Terrence: I do not think they matter. It is our natural tendency to put labels on things so a connection can be made to what we have seen before, when it comes to new designs. In a way, I’m happy they have very different ways to describe my designs.

Yuki: As one example of these representational figures, explain to me, how does a mermaid emerge? Does it come from formal, geometric inquiries—an imaginary altercation of normative bodily anatomy? Or does it come from mythology?

Terrence: In my world, mermaids always exist. It is more of an inquiry to the world or dimension I have never been. I feel mermaids are a metaphor for people who are marginalized in our society. In fashion, it is commonplace to be exclusive, which I strongly disagree with. I want to express my disagreement artistically rather than literally.

Yuki: You love to subvert understandings of space and geometry. In a few words, how would you describe the metaphorical shape of the world of Bad Binch TongTong?

Terrence: My world is malleable. If I believe in it, it will happen.

Model Helga Hitko.