The photographer and filmmaker joins Document to reflect on the parallels between male beauty and the colossal shapes of nature

Over the last few years, as the business of menswear has undergone a paradigm shift—challenging stereotypes of masculinity, engaging with new notions on gender expression, and seemingly renouncing an old system of thought—British photographer and filmmaker Britt Lloyd has sublimely articulated her stance on the movement, while bridging together the parallels of beauty found in both male body forms and the colossal shapes of nature. “At the time, too, there was also this notion of menswear being super feminine or hyper-masculine, and that very stereotypical view of it. It was missing the middle ground, or maybe even just being shot from a woman’s point of view.”

Britt is an experimental enigma of an artist, whose detail-oriented, yet beautifully abstract gaze offers a pathway into a realm of sibylline juxtapositions and holistic construction. Inspired by an astonishing amalgamation of tonality and varying interpretation, her images evoke emotions from their viewers, creating an unlikely connection beyond her work’s physical form, and transcending the boundaries of connectedness between man and nature.

Olisa Tasie-Amadi Jr.: Prior to our call, you stated, ‘I find interviews quite tricky. Language is definitely not my strongest medium to express myself, but I am sure we could find a way.’ That strikes me then, because it would mean that photography and moving image, in some sense, have become your primal form of communication. How does it affect your way of communicating with the world?

Britt Lloyd: I guess when you first start out and say you want to be a photographer, you don’t really know what you’re trying to do with your work. You’re not certain what exactly you’re trying to say. As you develop, you start to discover what exactly it is you’re attempting to say, either through growth, things happening to you in life, or even finding your interests and what attracts you.

Because it’s visual, it doesn’t always have a literal aspect of initial clarity. I think I found that the more I worked, the more I found what really spoke to me as a photographer. I’m sure in 20 years time, I’ll be saying something completely different, so I don’t think it happens straight away.

Olisa: Where did the notion of bridging together the parallels of beauty found in both the male body form and the colossal shapes of nature originate?

Britt: If I think back six years ago, I didn’t really know what I wanted to shoot—I was just working, trying to learn and figure things out, and it’s really beautiful how that journey progresses. I remember that I really enjoyed shooting menswear. I was put in a fashion environment and enjoyed exploring the different levels of masculinity through menswear. In the last six years, menswear has grown massively from what it used to be. It never really had that support system, in terms of photography, that womenswear had. When you look at the greats like Helmut Newton and Richard Avedon, they’ve always shot womenswear, and I think it stemmed from that. I’ve always wanted to shoot menswear to the same standard of beauty, or as elegantly as womenswear was being shot, because it should have that same standard, and maybe now even more.

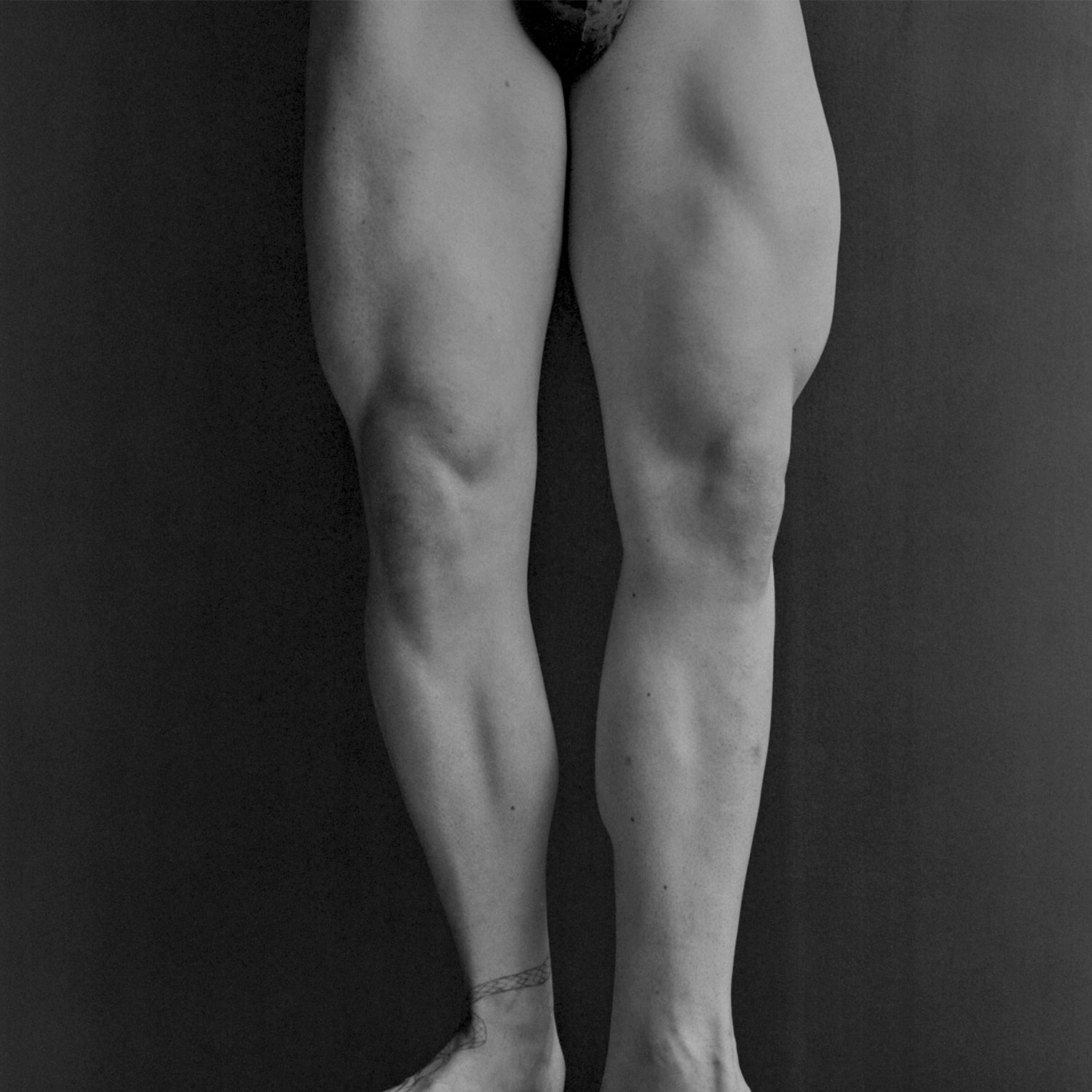

At the time, there was also this notion of menswear being super feminine or hyper-masculine, and that very stereotypical view of it. It was missing the middle ground—or maybe even just being shot from a woman’s point of view. That was the starting point of realizing you could use menswear fashion and male models and transform them into these incredible images. That led to me discovering other photographers that captivated me, especially nude photographers and landscape photographers. I quickly found the parallel, in these close-up nudes that transformed the bodies into big abstract shapes, with American photographers who would similarly transform landscapes. They both held this power and depth to them and slight darkness, and those were two things that I love, regardless of the different subject matters. I think they became the same thing at some point, so if I was to shoot a male form and a landscape, I would approach both things in very similar ways.

Olisa: You mentioned the middle ground between the delicate, feminine representation and the hyper-masculine side of menswear, and I think it’s amazing because it beautifully articulates the same thing that exists in nature. It has both the gentle and the powerful aspects to its existence—drizzles and thunderstorms, soft breeze and hurricanes, little waves and tsunamis—which nurtures the parallels your work focuses on. Do you think acknowledging that gray area helped pull it all together?

Britt: I guess it’s my response to it. In my personality, I have quite a strong sensitivity, in that I love the delicateness in images, but I also love the really dark tonality because it’s the biggest representation of emotions—images with really deep blacks radiating a lot of emotions from it. I like pulling those two sides together, and I guess I can apply that to shooting both nature and landscapes, and also to the representation of masculinity through photography. So I think it’s more of my approach to it, my middle ground, bringing both sensitivity and power to an image.

Olisa: What first ignited your interest in shooting primarily black-and-white? What was the conceptual drive?

Britt: When I look through old photography books, the images that captivate me are black-and-white. There’s a lot of older photographers that I have huge respect for and consider masters of the medium. I think people who shoot black-and-white, the tonality does the same for them as color would do for other people: manipulating the tones to create stories and what the image is trying to say. I use that tonality as a tool to really enhance what my image is about or trying to say, or the emotion I’m conveying.

Olisa: I think that perfectly communicates the understanding that due to the lack of color, the viewer is forced to focus more on the emotions or compositions present in the image, in order to understand it. And following that, I want to talk about the film, commissioned from SHOWstudio and YouTube, on Saul Nash’s Spring/Summer 2020 menswear collection which, to me, conveyed a perfect balance and representation of that notion of bridging the beauty that exists within the male forms and nature, especially being shot in black-and-white.

Britt: The video itself was a combination of three designers: Kiko Kostadinov, Ludovic de Saint Sernin and Saul Nash. For me, those designers were all so different, but such a good representation of how varied menswear is at the moment. Saul is a dancer himself, so he makes clothes that give the wearer this level of freedom, almost like air—he’s got hidden zips to give more expanse. Ludovic offers a sensual side to menswear and his clothes really hugged the shape of the body, almost the way womenswear is constructed. And then you’ve got Kiko, who is really interested in the design and the pattern cutting, and his work references are so different every year.

They all had different representations of what menswear was at the moment, which made it more beautiful. I spoke to each of them about what inspired the collections, the process, and what they were thinking about while making the clothes. It was me wanting to get in their head in order to properly portray that in a visual sense through film, using those references and individual stories. The juxtapositions between each of their works, I think, is what made it more beautiful. It wasn’t about being literal with the images, but attempting to get across certain emotions and feelings.

Olisa: Would you consider your work to be abstract in both its approach and output?

Britt: I find abstract film incredibly powerful and clever in the sense that you could make a completely abstract film, put dialogue over it, and it completely transforms what that image is trying to say. And for me, the power of imagery is its ability to manipulate what you’re thinking and draw an emotion. I think not coming from a film background made narratives somewhat secondary to me. I approach it a lot more in an abstract way.

Olisa: It seems the decision to capture your work through an abstract perspective wasn’t a conscious decision, as it gives you the boundless ability to communicate the focus of your work through other mediums for creative expression. Do you feel as though that is the case?

Britt: I’m not sure, I think I’m still trying to make film photography work before I take on anything else. In terms of the subjects that I photograph, I think my landscape is becoming much more broad.

One thing that I’d love to spend three months doing is photographing chairs that designers have made. I love furniture design, shape, and geometrical construction, and so I’d love to study them in different ways, highlighting the material and the character the chair might have. For me, I think it’s less my approach that’s changing than my subject.

Olisa: What do you think affects your changing subject matter above all else?

Britt: I think it’s probably just time passing and what your interests are. Like the chair example—I’ve always been interested in architecture, and a lot of the base of my photography is essentially form and composition. It’s not necessarily the body behind the image, but more the shapes that you can create with it. I think that’s why I like photographing the human body, because you can manipulate it in different shapes and forms. I think that’s why still life is amazing, because people can transform these simple objects, like a bottle of water or a vase, into something so beautiful.

Olisa: You’ve worked alongside visionary Nick Knight across multiple projects and shoots, and I’m curious, what was that experience like? What might you have learned in that time that has permeated into the personal work that you create?

Britt: I think that Nick’s approach to fashion film has always been driven by the fashion. Whereas when fashion films came out, people were hiring film directors. Nick’s background has always been, in terms of making a fashion image, it’s been within lighting, making the model look great, making the clothes look great, and all of that coming together in this one moment. In comparison to film directors who focus on what the model is saying, what the narrative is, and who the characters are, I think his approach viewed it as a still image, but focused on the 10 frames after and 10 frames before, which led to me creating much more abstract work.

Olisa: Where does a project start for you?

Britt: Sometimes it would be a person that I feel inspired by and want to photograph. It would always start with an idea, and from there it becomes about pushing and developing on it. I never plan my shoots too much, I always start with a small idea and explore the rest of it on set as it goes on, sort of letting your heart lead you and keep exploring it that way.

Olisa: Are you working on any new projects at the moment?

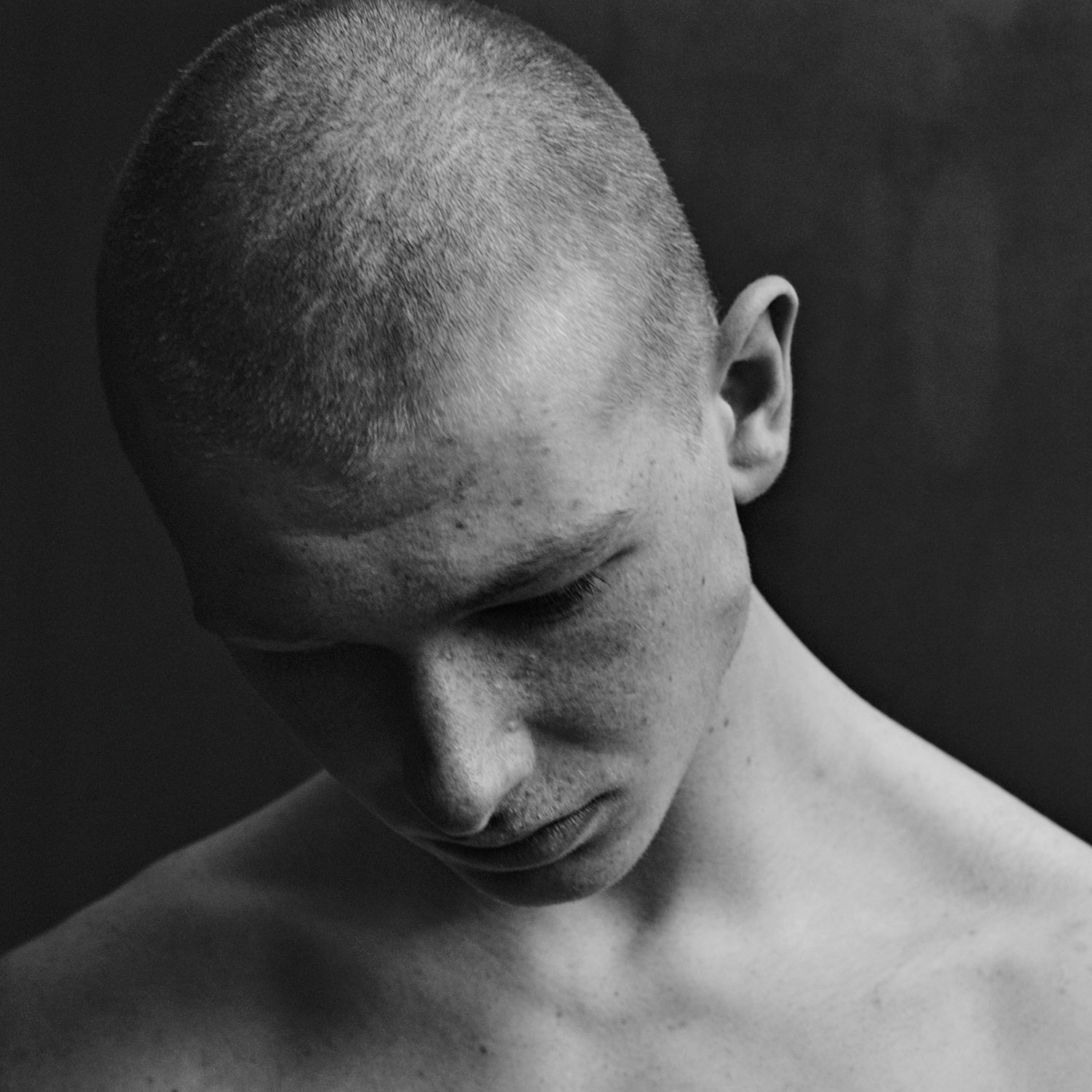

Britt: I’m doing a series at the moment. It’s quite simple actually; I’m shooting men with shaved heads, and I’m shooting just the back of their heads in my daylight studio, on a 10×8 camera. The image quality is incredible, and you get a very detailed image from it, but you still get that delicate feeling that film gives you. I’ve shot about 40 people right now but I want to shoot a hundred, and then I’d love to take the negatives and turn them into 10-foot prints, and maybe make an exhibition out of it. So you’d have these big walls filled with heads almost sort of looking down at you. The final result of them is that they’re super delicate and have this ominous feeling, and at the same time, it’s kind of aggressive or repressive. When you look at the image, you can feel your hand running over their head, feeling their skin, and spot all the little details. It’s a fine balance of both sides, and there’s a similarity to a huge mountain range, elaborating on the parallels I try to draw in my work. I’ve had dancers, artists, doctors, and so many different men. Some might have scars, and some might have tattoos. I think it’s also shown this nice representation of the variety in masculinity.