The late pioneer’s work made history, paving the way for a new generation of Black cinema

A bold policeman stranded in Mississippi. A smooth-talking jazz musician roaming Paris at midnight. An escaped convict intent on freedom. A kind-hearted drifter, a beloved teacher, a doting doctor—Sidney Poitier embodied all these characters and countless others. He commanded the screen, even when sharing celluloid with heavyweights like Tony Curtis and Katherine Hepburn. He is a figure forever cemented in American cinema, a maverick who paved the way for future generations of Black actors and storytellers.

A few weeks ago, I saw Sidney Poitier in The Defiant Ones on the big screen—a rarity, since classic films seldom grace the silver screen anymore. Film Forum, New York’s premiere independent cinema-house and nonprofit, was conducting a retrospective on Poitier’s filmography, given his recent passing this February at the age of 94. I was first introduced to his work as a child by my father, who came of age watching his films and, like so many other minorities in 1960s America, saw Poitier as the epitome of cool, a slick underdog to root for. After decades of racist films, such as Birth of a Nation, which depicted people of color as aggressive, unintelligent, and subservient, Poitier’s characters showed white America a side of the Black man they hadn’t seen before—he depicted alluring and empowered characters of color that American households could understand and identify with.

His films reflected the trauma, fury, and internal reckoning America was grappling with in the 1960s. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, which follows an interracial couple navigating the early ebullience of love after a crossing paths in Hawaii, was released in 1967, the same year that interracial marriage was legalized in the United States. Poitier’s early work didn’t shy away from the frightening underbelly of America—it put a light to it. In the crime drama In the Heat of the Night, the Ku Klux Klan are alluded to when a group of men driving a car with a confederate license plate, chase down Tibbs, played by Poitier. Later in the film, Tibbs slaps a racist cotton baron after being provoked (a script alteration Poitier insisted on). The shocked man remarks how there was a time he could’ve had him shot for such an act.

Poitier made history when he became the first Black man to win an Oscar for Lilies of the Field, and was the first Black man to share a kiss with a white woman on-screen in Patch Of Blue. He was well aware of the impact he had as one of the only Black actors in Hollywood in the ’50s and ’60s, and he wielded that power with care; he never took a role if the character was inhumane or stereotypical. “If the screen does not make room for me in the structure of their screenplay, [then] I’d step back,” he recalled in an interview with Lesley Stahl.

Poitier’s work lives on through the artists he influenced. Renowned director and comedian Jordan Peele cites Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner as a major inspiration for his critically acclaimed horror satire Get Out, with both stories revolving around a white woman bringing her Black boyfriend to meet her “liberal” family. At the 2002 Oscars, actor Denzel Washington asserted that, “Before Sidney, African American actors had to take supporting roles in major studio films […] He was the one we all followed […] He was the beacon.”

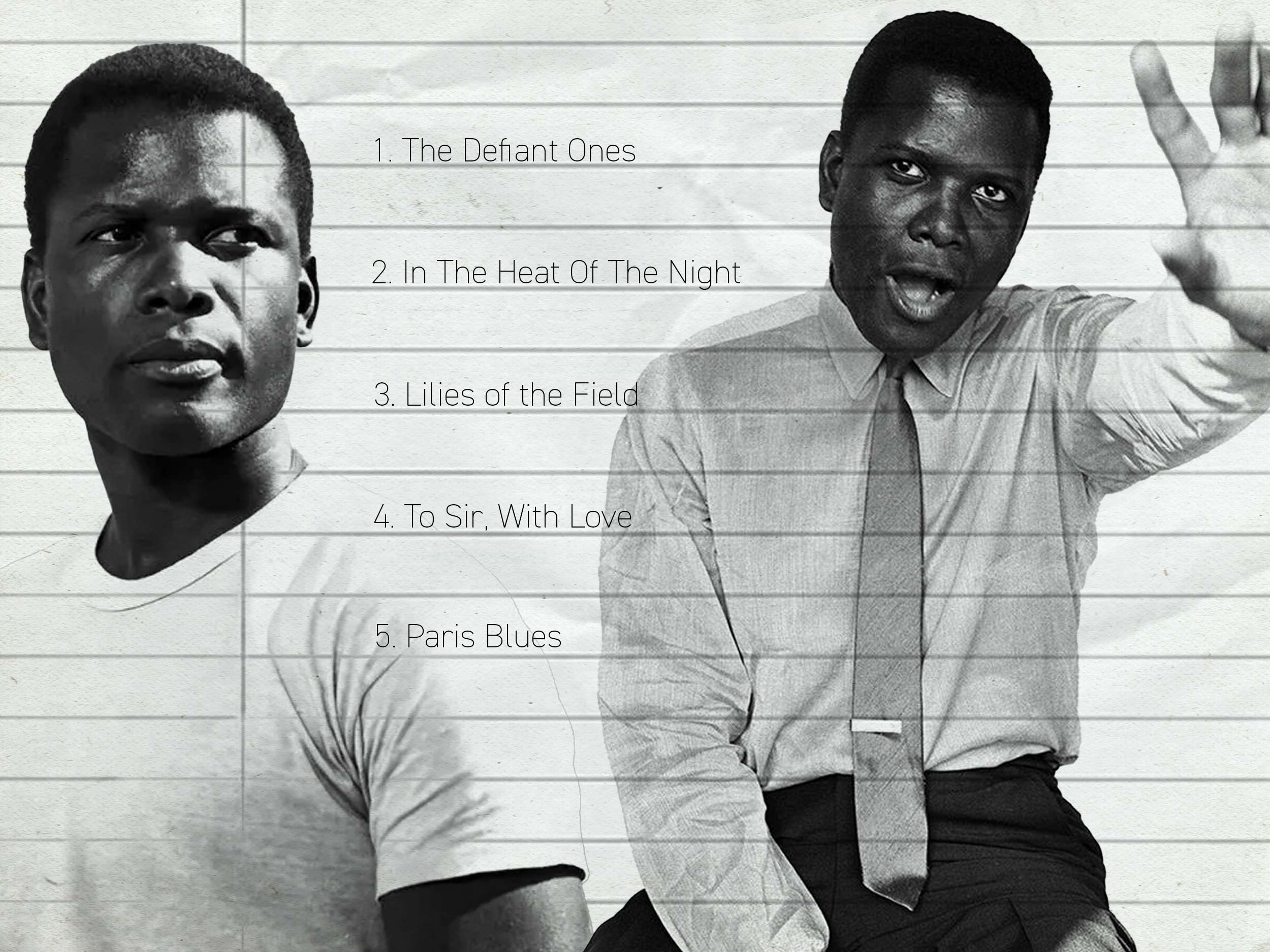

With a wide-reaching lexicon of 44 films, Portier’s early work is among his very best. And though his movies would be nearly impossible to rank, these five films are a great introduction for anyone looking to take a dive into his stories.

The Defiant Ones (1958)

Starring Poitier and Tony Curtis (Some Like it Hot, Spartacus), this film follows two escaped convicts on the run, initially butting heads before forging an unlikely bond. It pushes audiences to grapple with the issues of the time—ones which still permeate into society today—such as the use of the N-word, classism, and poverty. Curtis shines beside Poitier in this heartfelt tale of friendship. It’s an adventure story where, by the film’s end, you find yourself rooting for them both—prisoners or not.

In The Heat Of The Night (1967)

With a theme song composed by Ray Charles, this is perhaps one of Sidney’s best known films. Its infamous line ”They call me Mr. Tibbs” going down in cinema history (Lion King, anyone?). Much like The Defiant Ones, the film follows an unexpected friendship—only this time Sidney and his co-star Rod Steiger are both lawmen who must work together to solve the murder of a construction tycoon in a small Mississipi town. With layered characters and intimate camerawork, it’s not hard to see why this film became such a beloved classic.

Lilies of the Field (1963)

This list would be incomplete without the film for which Sidney won an Oscar. The film follows a drifter who stops by a monastery being run by a motley crew of East German nuns, struggling to get by. Despite his initial attempts to leave, he ultimately decides to stay and help the sisters build a proper chapel. Like a good concerto, this film hits all the notes—tugging at your heart and making you laugh. At its core, it’s a story about humanity, helping your fellow man and woman, and the connections we construct when we take those leaps of faith.

To Sir, With Love (1967)

A timeless classic that undoubtedly inspired films such as Lean On Me, Stand and Deliver, and Dead Poets Society. The film follows a Ghanaian teacher who—unable to secure a job in engineering—takes a teaching position in one of London’s grittier neighborhoods. His candor and empathy earn the respect of the rebellious youth, changing their lives as they transform his. The film did so well globally that Columbia Pictures conducted a study to pinpoint its success. The reason? Poitier, of course.

Paris Blues (1961)

Poitier and Paul Newman’s powerhouse performances are the bread and butter of this movie. The film follows a couple of American expat jazz musicians in Paris who fall in love with two radiant American gals on vacation (Joanne Woodward and Diane Carroll). Ram (Newman) is an obsessed artist, who chooses music above everything and everyone else; Eddie (Poitier) sees Paris as a green zone, a place away from the hate and racism he knows all too well back home. The film examines other elements too, such as drug addiction and the artist’s struggle. With a score by the great Duke Ellington, it’s one of Poitier’s lesser-known gems. If that doesn’t sell you, then seeing Poitier and Louis Armstrong musically dish it out should.