The Swiss artist discusses his otherworldly portfolio and paying homage to the rattlesnake in his painting of Joan Didion for Document’s Tenth Anniversary cover

Otherworldly faces in every color stare with piercing gazes. Magical landscapes show a sun rising over a body of water above curved clouds. An intense red glow emanates from a cluster of trees. Welcome to the world of Nicolas Party. The Swiss-born, New York-based artist, who also has a home in Brussels, Belgium, always had an affinity for art.

Born and raised in Lausanne, Switzerland, Party grew up in a picturesque city on the shores of Lake Geneva overlooked by the Alps. Before attending the Lausanne School of Art, and the Glasgow School of Art, he hopped train cars as a young graffiti artist eager to paint throw-ups on their walls. Party claims his knowledge of art history is surface level, but in conversation, his references run from Tintin comic books to ’90s graffiti to 19th-century Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler and 18th-century Venetian Rococo artist Rosalba Carriera.

Like so many talents throughout the centuries and of his time—Mickalene Thomas with old Jet magazines and Impressionist paintings, Demna Gvasalia with ’90s hip-hop references and Cristóbal Balenciaga silhouettes, and Virgil Abloh with, well, everything—Party samples and remixes elements of art history and pop culture to create something that is entirely his own.

His exhibitions, like the group show Pastel he curated at the FLAG Art Foundation in 2019 and Sottobosco at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles in 2020, feel as if you’re wandering through the insides of a peculiar jewelry box—all at once alluring, mystifying, and eccentric. In his world, the works are rarely hung against stark white walls, but rather against rich tones of eggplant, marigold, emerald, thistle, cobalt blue, and more.

For Document Journal’s Spring/Summer 2022 issue, Party painted a portrait of the legendary author Joan Didion, who passed away last December at age 87. In it, Party pays homage to the rattlesnake—a motif in Didion’s writing that Party discovered while reading Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The Year of Magical Thinking—by placing one winding over her chest.

The works featured in this portfolio will be on display at Red Forest, Party’s exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong that runs from June 30 to September 23. I spoke with him about the artists who helped shape his practice, why he refuses to conform to the standardized white wall display, and the time when a Milanese police officer pointed a gun at him.

Ann Binlot: I want to start out with your youth. You were into graffiti.

Nicolas Party: My youth? That’s right now.

Ann: [Laughs] How did you discover graffiti?

Nicolas: I started in the ’90s when I was 14, 15. There was no internet then. There was only one local magazine, that’s how I discovered it. Then they opened this hip-hop street store in my hometown, Lausanne, which is a small city, and there they had three magazines. The only way to have access to non-mainstream culture was probably magazines. Now it’s easy to have access to any subculture in a second. Back then, I discovered what people were doing around the world and mainly in Europe through those magazines.

At that time, the golden age of [graffiti] was New York in the late ’70s. The style changed a lot in the ’90s, it was more elaborate. Germany was very big into it—Berlin, Munich, all those places. So that’s how I started, and I did that until around 2001.

Ann: What was your tag?

Nicolas: I had a bunch, but one was Real. There was Seam. You have a bunch of names, but if you get caught you have to change them. Sometimes you change [your tag] because you feel like you’re pretty close to getting caught.

Ann: What was the craziest thing you did as a graffiti artist?

Nicolas: The train expeditions. When we were young, it was quite a thing. You have to put something [over] your face so you don’t get recognized on the cameras. You have to climb those fences, you have to avoid the police. You [scope it out] the night before to know exactly where the guards are. Italy was a bit less guarded than Switzerland in some places, and it was a bit out of control there. When we were [in Milan], some gangs were doing graffiti—which was really not common—so the police were very on edge. Every time we got chased by the police in Europe, it was not that big of a deal because I’m not Black, so I was never scared of getting shot. In Italy, the first thing they did was point a gun at us. There was a big wall and we turned around and the police were there pointing guns at us. We were very shocked. We stopped, they got us, and that was the start of a long day with Milanese police. They discovered we were Swiss and decided they would have a great time with us at the police station, so they sprayed our clothes, took all our money, and said, ‘Get the fuck out of here.’

Ann: Oh, wow. So they were corrupt?

Nicolas: They were just having fun. They were like, ‘Okay, this is ridiculous. These kids from Switzerland, we’re just going to scare them from coming back.’

“It’s my own because I did it. If it looks very similar to another person’s, it’s still my own—it just looks very similar. If someone prefers to look at the other [artist’s work], it’s more about the viewer.”

Ann: What drew you to fine art? Did you visit museums and galleries when you were younger?

Nicolas: While I was doing graffiti I was also doing very traditional landscapes. I was always really into art when I was a kid. Way before the graffiti, I was already doing a lot of watercolors, even oil painting. My parents were very supportive, they really liked that I was doing that. They bought me books on how to paint landscapes, how to use oil paint, it was all going on in my attic and I would go in there and paint. I grew up in a very picturesque place with a lake, so I was painting the landscape in a very direct way.

Ann: How have landscapes played a role in your work? They are still a very big part of your practice.

Nicolas: Growing up in that landscape had an effect. It’s in a vineyard area, so a lot of the labels of bottles were made with watercolors, and I always loved that when I was a kid. But now I realize that there’s a broader culture of landscapes in a place like Switzerland.

Ann: So you went to art school in Lausanne and Glasgow. How did those experiences further shape your practice?

Nicolas: Glasgow was really a big switch in terms of leaving my hometown, because Switzerland is a bit insular. It’s neutral and everything’s nice, so people don’t necessarily want to leave. They are like, ‘Why are you leaving? It’s great here.’ The social system is pretty good. There’s a lot of money. For me, Glasgow was really trying to explore something else and get out of this little cocoon. It was a great switch, because Glasgow was the opposite of Switzerland—not very comfortable and cocooning. It was rough and quite poor, and the weather was terrible—but I loved it. There’s a counterbalance of people, because the city is difficult to live in, [so] the people are really a composite of the city’s roughness and its history—[it was] great energy for starting out a career. The school was quite cheap compared to the US and other places in the world, so there were a lot of people from everywhere, even Canada, America, Asia. It was great because in Lausanne, there was very little diversity.

Ann: Some artists prefer not to be influenced by other artists, but so many others like Otto Marseus van Schrieck, David Hockney, Pablo Picasso, and John Armleder, to name a few, have informed your work. You’ve also curated shows featuring other artists’ work, including the Pastel show at the FLAG Art Foundation and your recent show at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. How do you take other artists’ influence and make the work your own? And why is it so important to you to highlight the work of other artists?

Nicolas: It’s my own because I did it. If it looks very similar to another person’s, it’s still my own—it just looks very similar. If someone prefers to look at the other [artist’s work], it’s more about the viewer. Having a recognizable personal style doesn’t make you a good artist. I never really questioned myself—if it looks too much or not [enough like] mine. I’m just doing my thing. I don’t think anybody in our day can claim that nothing similar was ever made.

Ann: Everything’s been done already.

Nicolas: Yeah, but it’s been that for a long time. Even the masters of the avant-garde, like Picasso or Picabia. Cubism, you can put it next to a lot of images and go, That’s very similar. It’s a bit of a myth, this originality thing. What is more important is being an individual. Nobody is me, and nobody is you. It doesn’t mean it’s good or bad. It’s just a simple fact.

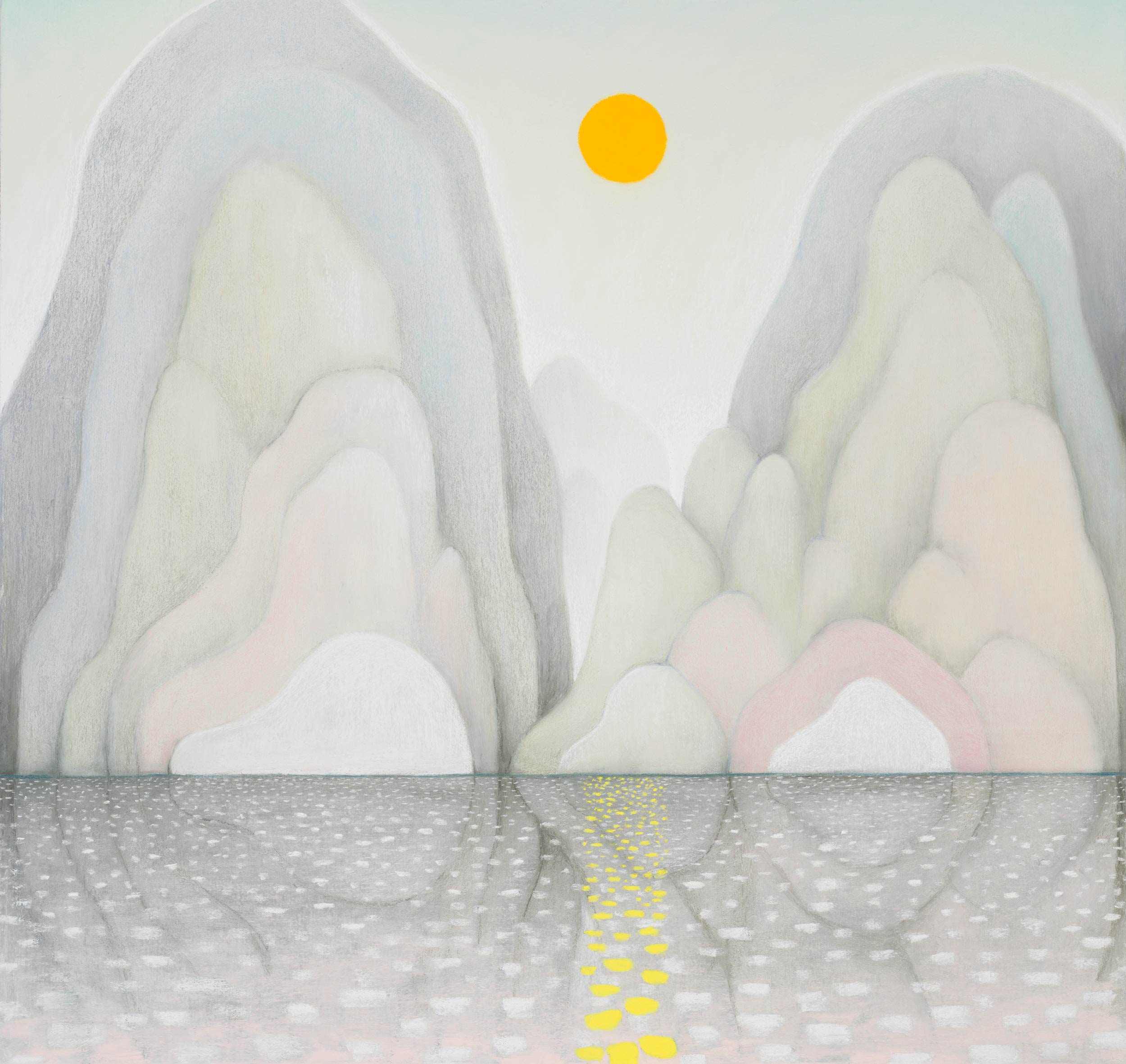

Let’s say I do the sunset that I did. There’s the sun, and the mark of the sun on the water is a straight line. I took that from a painter called Félix Vallotton, it’s more or less exactly the same. But if you see a moon, for example, I did that exactly the same too. If you google ‘Vallotton’ and ‘sunset,’ it’s the first [image you see]. That’s the one that I took for my sunset. I take a painting and I just do exactly the same. That’s more a sample or an homage. Back in the day, a lot of artists would do a copy of [another] painting. Sometimes I do that too, but my painting is quite different.

Ann: I love how the exhibitions I’ve seen of your work do away with the white wall. Why do you choose to do this?

Nicolas: What is interesting is asking any artist, ‘What color did you paint a wall?’ If the artist says, ‘Oh, I didn’t paint it. I don’t have a color, I just put it in white,’ that will imply that the person feels that white is not a color, that white is a neutral value. White is a color with a very specific history. Hanging things on white is very tied in with our Western idea of what white is—a non-color, a neutral color. And that is completely wrong culturally, historically, and even scientifically. You choose white because you think it’s a great color for your painting, which is often not the case. Very often white is just a bad color for hanging or seeing things. The example I often use is if you take a photo of someone and the sun is [behind them]. Usually you’re gonna say, ‘Oh, it’s not great because there’s way too much light on the back, the subject is going to be very dark.’ You don’t want that. This is exactly what a white wall does to a painting, because the color white rejects most of the light.

The cult of whiteness is connected to purity, to cleanness. It’s not a scientific value, it’s a cultural value. It became super fashionable in the ’20s in Italy with Mussolini, with the fascists—it’s difficult to not make a little bit of a connection anyway. But also, colors are complex and dense. I mean, if you go to the edge of the white cube, if you go to a big gallery, and everything is super white—whites on the floor, concrete, or whatever it is—it’s a look that comes with a cultural history. Every time I go to Chelsea I’m like, ‘Well, it’s a great show, but it’s very sad that it’s on white walls because the show would be much better in another color.’

Ann: It comes out really nicely. Do you think about social media when you conceptualize an exhibition and lay it out?

Nicolas: It’s not social media. It’s looking at art through your phone. What matters is you see things through a very small screen, which is very different from [looking at art on] the computer. Everybody has a phone and the only person that can say, ‘It doesn’t have any impact, my work or my vision is not polluted by the phone,’ will be a person that has no phone and has never looked at images on a phone. I’m extremely affected, because I’ve been looking at art on the phone for a decade now. My Instagram is probably, I don’t know, 70 percent art, so I look at art much, much more on my phone than in books.

Ann: Is that why your color palettes are so vivid? Because they really bring the viewer in.

Nicolas: The very vivid palette is definitely from when I did the graffiti. I think that had a very big effect on my eye, because graffiti has to be seen very quickly. And you do it at night. You have to do a very bold, graphic color. It’s basically a logo to have big so you recognize it very quickly. So doing that for 10 years, when I was a kid, definitely formed my eye. I was a slave to it.

The other thing is, I was reading a lot. I grew up with comic books—Tintin and Asterix, especially Tintin. It’s a very clear, graphic language that you recognize super quickly, it’s not blurry. I looked at Tintin a lot when I was a kid.

“[Joan] has this amazing approach of being very powerful and not overwhelmed by a situation, but also embracing her own fragility and the fragility of the world around her.”

Ann: You have such a vast knowledge of art history. Do you just absorb everything around you? Books, exhibitions, whatever? It sounds like you know so many names and points in history.

Nicolas: I’m very non-academic. I don’t have a technical or in-depth knowledge, I’m very superficial.

I do love looking at images, so I will buy a lot of books, and I’ve been reading biographies. So looking at the books, and that’s it. I’m definitely not ready to do a big conference with actual dates and names, connections, political context. I just eat it up, and I love it.

Ann: Let’s talk about Joan Didion. Had you read her books before discussing this cover?

Nicolas: Yeah. When I did the cover I was reading a little bit more of Slouching Towards Bethlehem. The last book that I read was The Year of Magical Thinking, where there’s also a rattlesnake. The book that sounds very relevant right now was Play It as It Lays, and actually the rattlesnake is very present in that book. I was thinking about that book now because [we’re in] another funny moment of history with all this discussion about abortion and women’s rights. [Didion] obviously had this [theme] of traumatic abortions. People are probably going to put it back out and say, ‘See, it’s not great when you can’t do [legal abortions].’

Ann: Why did you have this snake winding around her chest? Is it a symbol of her power? Is it a symbol of her fragility? Or is it both?

Nicolas: Yeah, probably both. Her writing is very powerful, but also she’s embracing her own fragility as a woman, as a human being, going through different events in her life—tragedy, but also the people that she’s interviewing or hanging out with. She has this amazing approach of being very powerful and not overwhelmed by a situation, but also embracing her own fragility and the fragility of the world around her, so she was able to navigate quite complex networks of people—people with pretty extreme personalities and lifestyles.

“Art has a long history of depicting nature—or even [defining] what nature is and what the differences are between human and nature, culture and nature. Nowadays we have [reached] this peak of anxiety about nature and the planet.”

Ann: What’s up with your mushroom haircuts?

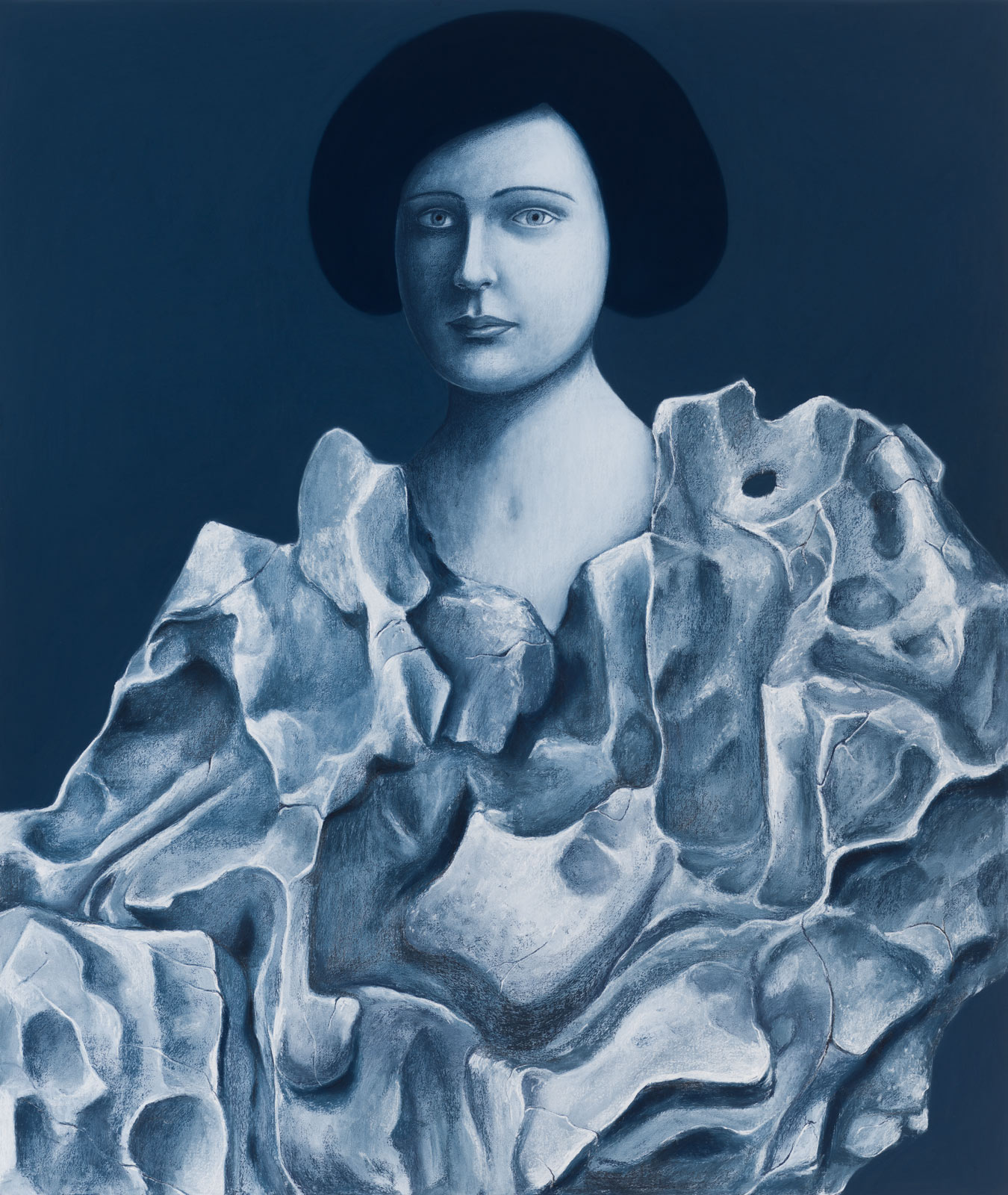

Nicolas: I’m doing more and more of my mushroom haircuts. That was funny with Didion, because she had this kind of mushroom haircut naturally. I also look at a lot of the Renaissance portraits, and obviously they have the halo of saints—the hair sometimes becomes a hat, or sometimes becomes a spiritual place. My haircuts are sometimes a mix of hats, and something else, and the hair—so that’s why, quite often, they’re kind of flat. I also like my portraits being not gender-identified in the first place. Very often, as soon as I do my little hats or haircuts lower than the ear, people say it’s a woman, and if they’re [above the ear], people say it’s a man.Even if it’s exactly the same face, which is kind of interesting. I guess that’s how we use hair in our culture—long is women, short is men.

Ann: Tell me about the work in the portfolio. Who are the subjects in the portraits? What inspired the landscapes with the fire depicted? Is it related to the Red Forest painting that was in the Montreal show?

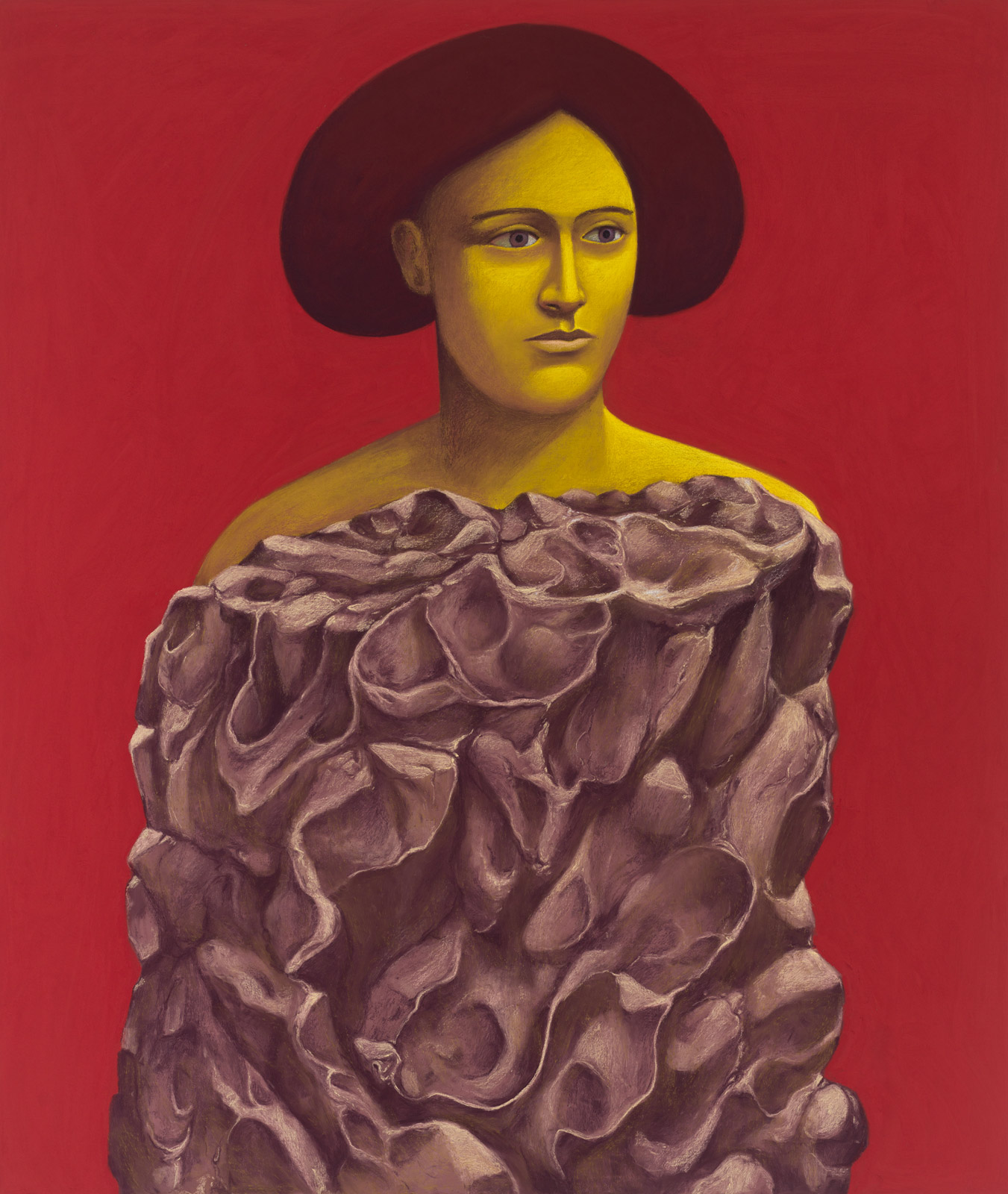

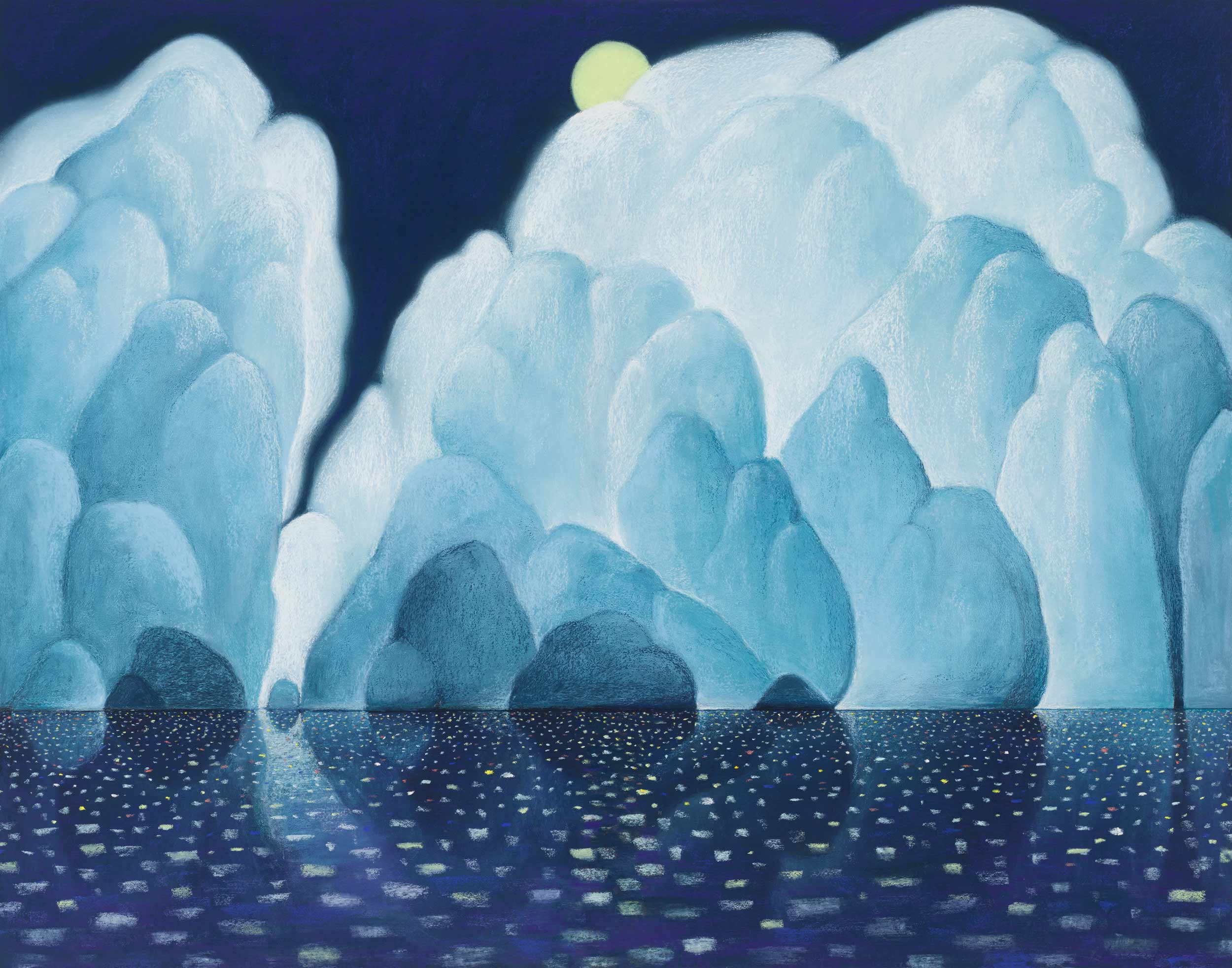

Nicolas: There are three series of those clouds on the water, and there’s a reflection of the clouds on the water. And there’s the fire which is basically those trees. Then there are four portraits, [part of] this series of photos that I’ve been doing. It’s gonna feel a bit like a collage of more or less classic portraits. The torso is made out of different elements. And for this show, all the bodies are made from different meteorites, which is funny because they’re usually quite small. They’re really blown up here. All the elements are in the exhibition; fire in the landscapes, then earth, water, air, and this cloud. Then that came back to the meteorite idea. The whole meteorite is very often basically metal. In China there are five elements, the fifth is metal. This was an interesting play on the element and how, in different cultures, [we have a] different way of perceiving elementary things. The forest fires I made for that reason, [pointing] very directly to something that is very present in our day.

The show in Montreal was talking a lot about our relationship with what we call nature and our environment. Art has a long history of depicting nature—or even [defining] what nature is and what the differences are between human and nature, culture and nature. Nowadays we have [reached] this peak of anxiety about nature and the planet. We believe that we are harming the ecosystem at a very rapid pace and will be maybe not the first, but one of the species that will pay one of the biggest prices for all those changes.