Thirty years after the release of 'My Own Private Idaho,' the filmmaker opens up about his artistic practice for Document’s Winter 2021/Resort 2022 issue

My Own Private Idaho, which turns 30 this year, begins and ends with the late River Phoenix standing alone on an empty highway. The road film is a uniquely American genre, and Idaho evokes the individualism and cruelty of the West. Phoenix’s Mike is free and yet unable to escape the conditions of his life and of his body—he’s the core of a sexual Bildungsroman that morphs into Shakespearean tragedy.

Gus Van Sant isn’t afraid to depict the unconventional and the underground, centering the film on characters at the fringes of their world. My Own Private Idaho follows Mike and Scott, played by Keanu Reeves, who are queer. They are also sex workers and spend a portion of the film living in an abandoned apartment building with a rowdy band of young street hustlers. Mike, a narcoleptic, suffers a great deal of trauma regarding his mother, who he is searching for throughout the film. In the 30 years since the film’s release, the rise of the internet and social media has provided young people a space to discuss their sexual identity and trauma, arming them with a new vocabulary with which to express themselves. Conversations about queerness and sex work have entered the mainstream, even if the violence of marginalization still exists. My Own Private Idaho was groundbreaking and continues to feel singular in its vision today. Van Sant gives Mike and Scott breathing room to exist beyond their identity; he subjects the two to the universal forces of love and loss, favoring compassionate ambiguity over exact, digestible labels.

Born in Kentucky, Van Sant first seriously considered filmmaking during his high school years in Darien, Connecticut. His talent for zeroing in on the heart of societal tensions extends across his entire body of work. Elephant, released just four years after the tragedy at Columbine High School in 1999, dives into the events leading up to, and including, a school shooting with an unflinching perspective. While many films have since approached the topic from the sidelines, no other has dared to run at the core of the uniquely American pattern of violence through depicting the shooting itself. But Van Sant’s ability is not restricted to darkness. In his latest film, 2018’s Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot, he traces the journey of a disabled alcoholic who finds renewed purpose in drawing cartoons. Van Sant’s auteurism serves as a model for a new generation of creatives, encouraging bold and humanistic storytelling.

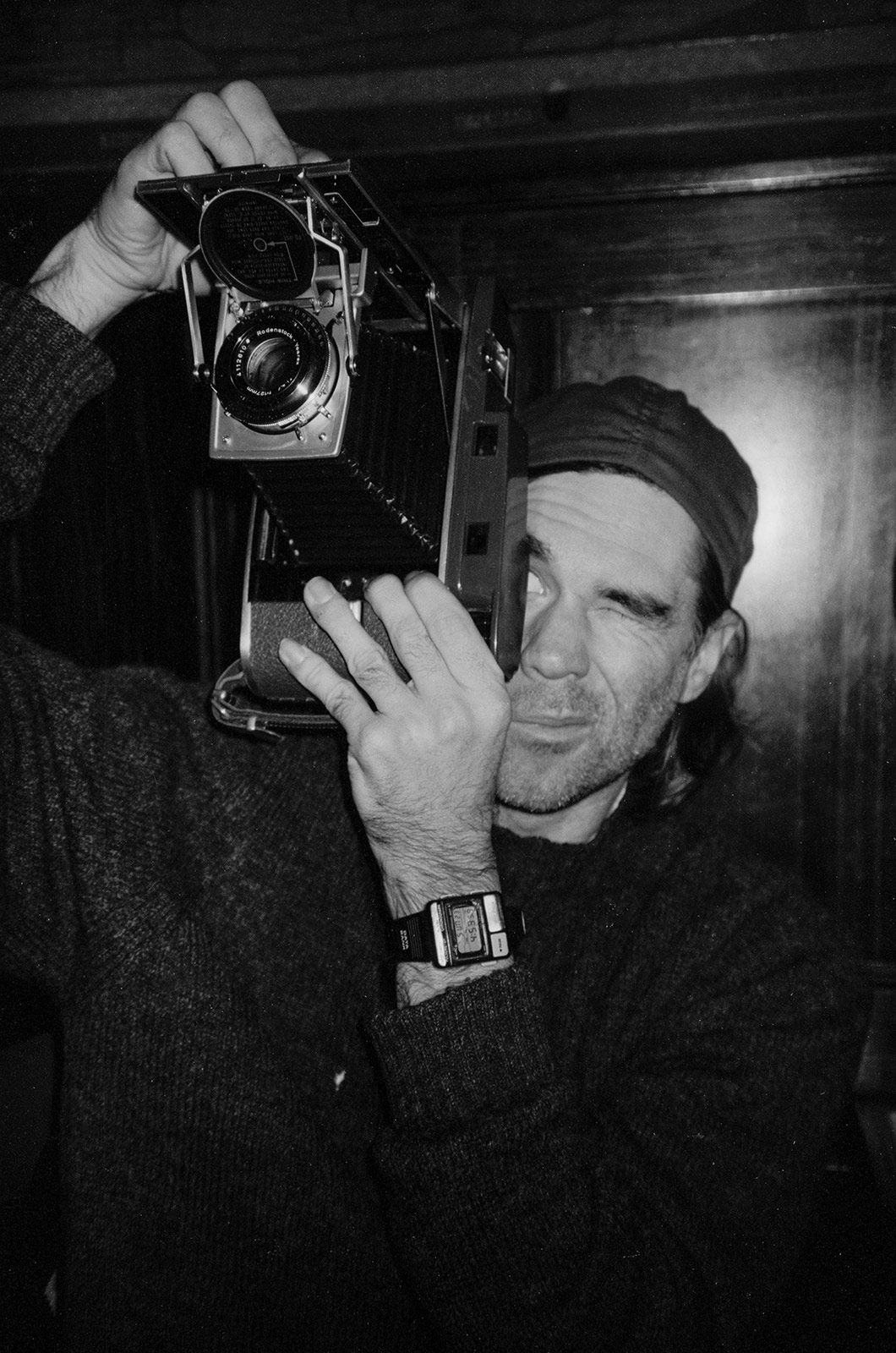

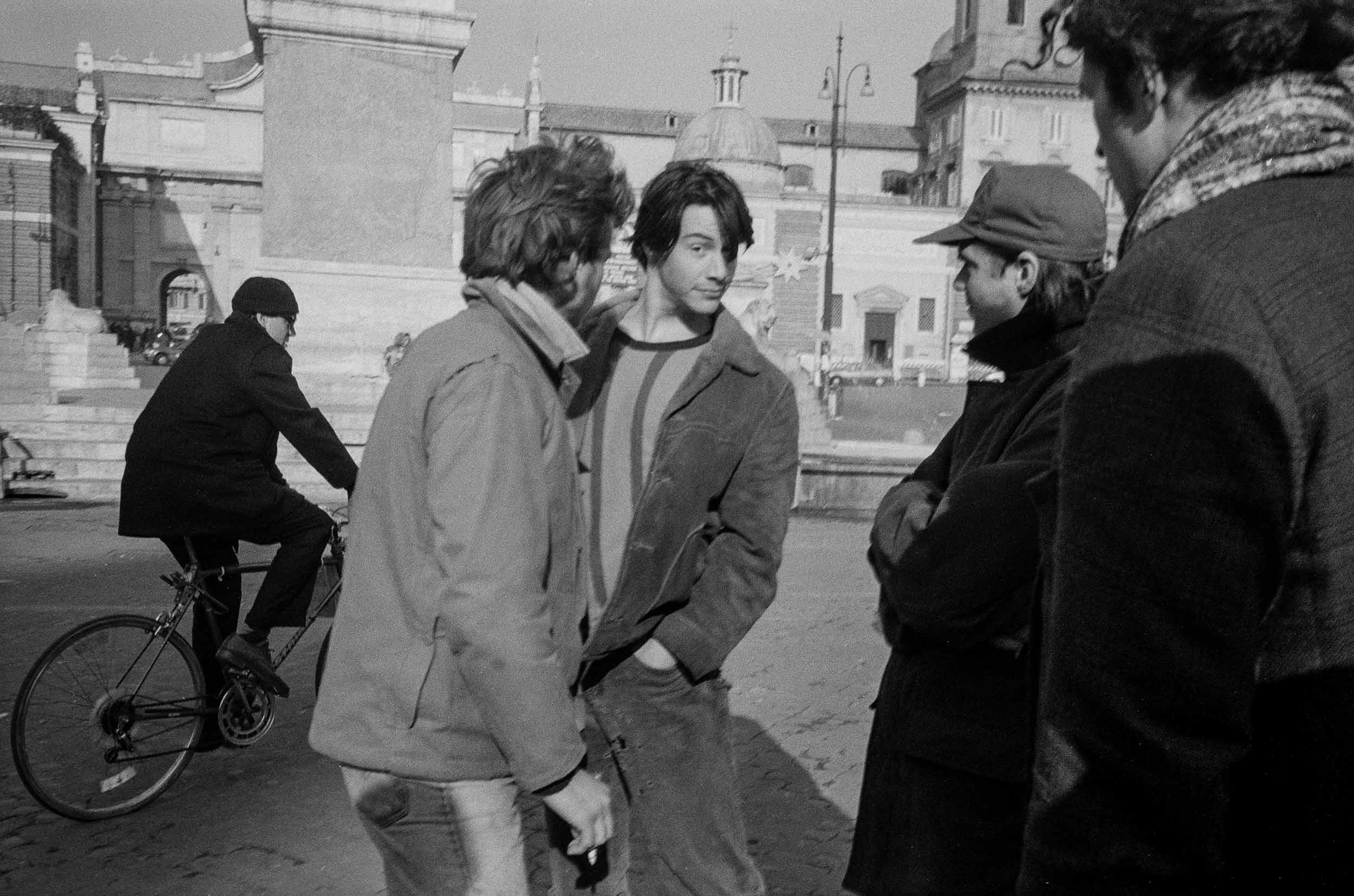

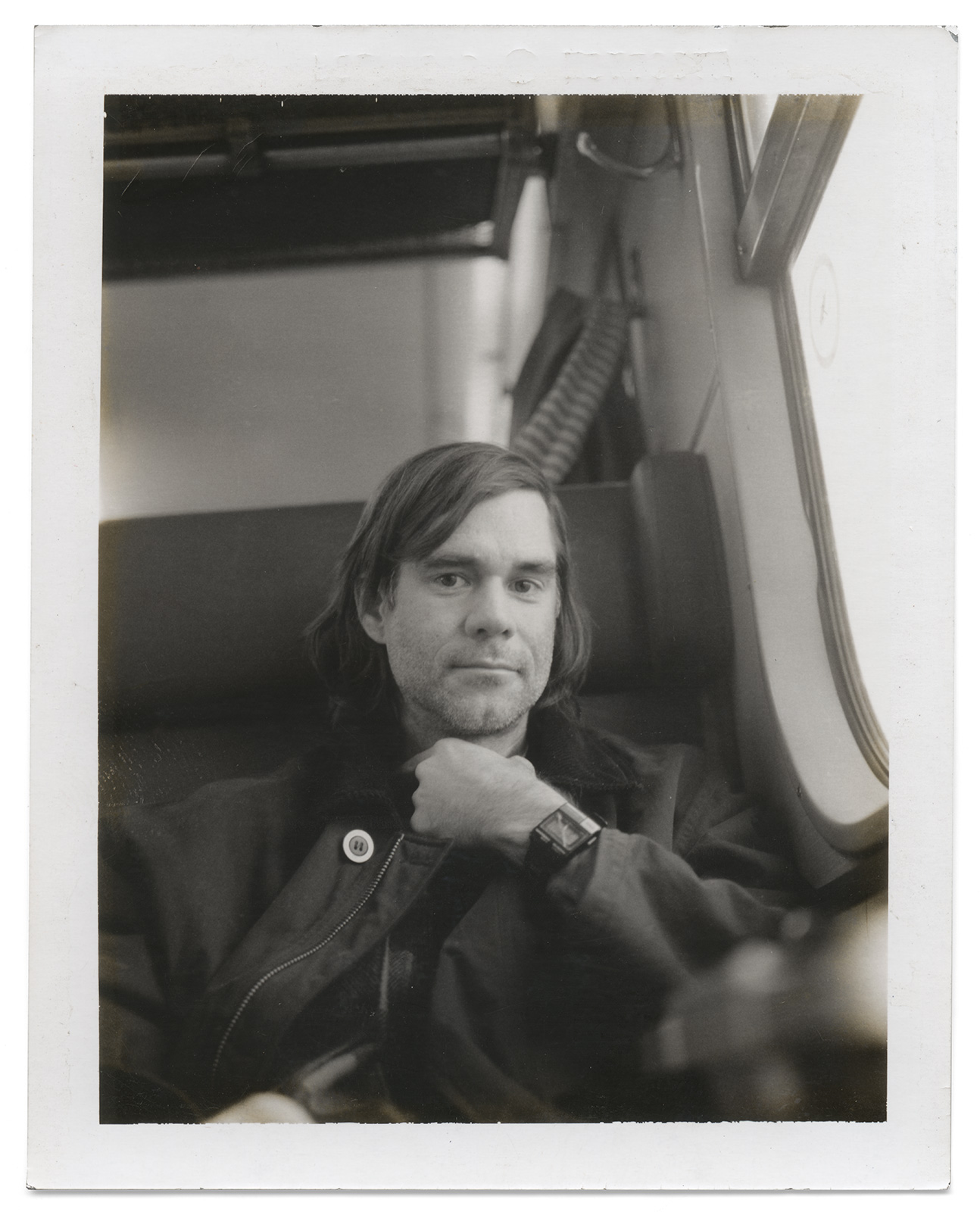

In a new book, The Art of Making Movies, published in November, he collaborated with arts and culture writer Katya Tylevich to give a window into his artistic practice. Shortly before the book’s release, Van Sant joined Document editor-in-chief Nick Vogelson to discuss his approach to character building, filmmaking as a collage medium, and confusing Pier Paolo Pasolini on a trip to Rome, and Gus’s close friend, the photographer Paige Powell, shares never-before-seen images from the filming of My Own Private Idaho.

Nick Vogelson: Your book, The Art of Making Movies, gives a fascinating insight into your history. Your artistic practice is really quite diverse, in terms of filmmaking, painting, writing. What makes you feel creatively satisfied?

Gus Van Sant: I don’t know; I think just finishing something is satisfying. All of it is part of the same thing, whether it’s a film or—now I made a play this year—or else photography, or painting. It’s all a process that requires a lot of different disciplines. So that’s satisfying, just accomplishing something.

Nick: I know you’ve been painting since you started filmmaking. I’m curious, with all of these concurrent artistic interests, what is it about film that made it your main outlet?

Gus: Well, I started making films at 16, which was four years after I was painting quite a bit at 12. I was young, but we had a great teacher. I was actually painting and entering a local township [art show] every year. The access to films came through a different teacher. We had these two great teachers in the middle school I went to in Darien, Connecticut. It was a pretty progressive school, enough that the English teacher was having us read Samuel Beckett and Lord of the Flies at 14. But he was also showing us films [from Canada] because the Canadian film board had a really organized program. The films you could get from Anthology Film Archives probably weren’t safe for 14-year-olds, so the Canadian film board had a scholastic series of pretty cool films. He was also having us read Marshall McLuhan, the medium is the message. The films he was showing us related to that kind of modern advertising chaos that was going on in New York. Some filmmakers from Canada were actually block printing on the film in a Stan Brakhage sort of way, or drawing directly onto film. So there was a direct connection. I thought maybe there was a world for me as a painter in the film world, so I bought a camera. I worked in the Kushner Building, what’s now 666 [Fifth Avenue]. I had a summer job in my dad’s company, and across the street was the Museum of Modern Art, so I could go see some of the films there. There was a camera store in the building, and I used most of my money from the summer job to buy this fancy 8mm camera.

Nick: That must have been so exciting.

Gus: I started making films with my friends, and I also drew [on] and scratched film. When I went to art school in Rhode Island, I was going to major in both painting and filmmaking, but I decided to just go into film. Back then, in the early ’70s, it was not a really good idea to be a painter, even though in the ’80s there was kind of a boom for young painters. But in the ’70s there was not, and everyone was pretty much struggling. It wasn’t something you chose as a job unless you were very committed. I was interested in film, enough to go to Hollywood after I graduated just to see if I could find work there. Which I kind of did. I worked for a director, but I didn’t really get very far. I made a film, which was great, but it didn’t get into any festivals. The film world was hard enough that you had to put pretty much all your effort into it.

“I taught myself to really worry about what I thought about the film rather than try to make something for an audience.”

Nick: One of the throughlines in your work is that you’ve always stayed true to yourself, at least that’s the outward perception—that you’ve made creative decisions based on your interests, sometimes with respect to the cultural climate, sometimes just making the films you want to make. As a creative individual, what do you think about failure? Does it play into your process when thinking about projects, or do you just disregard it altogether?

Gus: The first film I made, I worked with a lot of comedians, mostly in an assistant capacity—not writing comedy, but they were writing comedy. The first thing that I made was not intended to be a comedy, but it was similar to my other films; like, halfway funny [laughs]. I think I failed right at the beginning. I couldn’t even get it into any festivals; I tried, like, five or six festivals. So I just kept going; I kept working. The next film was Mala Noche. I chose to use someone else’s material, rather than my own. I was adapting a friend’s novel. It was queer perhaps, but it wasn’t really what you would think of as something made within a gay neighborhood or a gay sensibility. [The author and protagonist] Walt Curtis was a man on his own, a mad poet who worked in a grocery store. So it had a lot of things about it that were kind of transgressive. I taught myself to really worry about what I thought about the film rather than try to make something for an audience. I felt like if it was done correctly, [because] Walt’s book was so great, it would have an audience. I was also convinced that the transgressive qualities were not places that you could go with a dramatic story or film, so I was sort of surprised when it was played and received well. I just continued on. Drugstore Cowboy was an adaptation of a novel that was similar but with a different cast of characters. But My Own Private Idaho, that I did write myself, and was kind of using a lot of the things I learned in school from Marshall McLuhan.

Nick: Would you mind unpacking that a little bit?

Gus: Well I was really playing with the medium physically. I think I was actually using characters that came from different places, including Shakespeare. One of the character traits for the protagonist is narcolepsy, which completely is related to a character in Silas Marner, a George Eliot novel that you read in school. So it was kind of pasted together [from] all these storytelling sources into a collage.

Nick: The narrative of My Own Private Idaho feels very timeless, but the film could also be made today, and all the same circumstances exist for people in one way or another. If you were going to make that film today, how would it be different or how would it be the same?

Gus: You mean make the subject, or in terms of style?

Nick: The subject.

Gus: You mean the kids on the street. I think probably pretty close [to the original]; it was made about the same types of people that are on the street today. The kids in My Own Private Idaho were actually street workers that worked in a place called Camp, and it was called Camp because, I learned later from an older gay man, there used to be an actual camp on that block of homeless people, from the Depression. Rich men from the hillside would drive down and pick up young guys and pay them for sex. It was a really Depression-era piece. [The kids] had no idea why they were calling it Camp. The name was handed down. But you can find the same people [today]. I don’t know if you can find sex workers, but you can find the same characters. When we filmed it, we filmed in some old hotels where there were kids living. They weren’t the kids in the movie, but you could see them flash by [as they] ran upstairs.

“I think the thing that all my movies have in common is that there’s a group of people that come together who form a family. They’re not blood-related, but they’re related in their ideas, in their desires, or in their places in life.”

Nick: You’ve made so many different types of films over your amazing career, from independent to big-budget studio productions. What pops into your mind when you’re trying to decide what stories to tell? I’d imagine you’re coming across a lot of ideas. How are those decisions made?

Gus: I think it’s literally just the story itself; everything else will hang on to the story. But sometimes the story and its relationship to the setting is what’s happening. Sometimes the setting comes first, and you can apply the story to the setting. But the setting is probably the most important for me. I think the thing that all my movies have in common is that there’s a group of people that come together who form a family. They’re not blood-related, but they’re related in their ideas, in their desires, or in their places in life. They are somewhat forced together by their situation. That hangs over the stories. That’s something that just happens magically, it’s not a conscious thing. I made four films that were about outsiders. Good Will Hunting, [the characters] weren’t outsiders, they were South Boston kids. Good Will Hunting had an obvious hero, but Will Hunting was sort of a castaway character, and he did find a family of friends in South Boston. So the family aspect still played into it. I’m usually just looking for what I think of as a story, but it’s usually a setting.

“So those things start to tie together until you have a big mass of all kinds of interacting ideas, meanings, reasons for things, results for things, symbols for things. Filmmaking is sort of a collage medium.”

Nick: I find it very interesting how, when you make certain films, they speak about the moment they are in, as well as to more timeless, larger truths. I’m curious what type of narratives you are interested in now—what types of things you find exciting, and what types of stories you want to tell in the future.

Gus: I don’t know, I think I ran out of them [laughs]. I read one writer say that he wasn’t writing about singular characters, he was writing about everyman characters. So if he had a post office worker in his story, it wasn’t just this post office worker, it was all the post office workers in history. I was taken by that, because it was what I always thought I was doing. Your character is representing everybody, not just this one character. He interacts with another character that represents other everybodies, and they’re in a town that is everybody’s town, in a world that’s everybody’s world. In that way, you can draw meaning in many directions, including into the past or other places. It starts to become a stew of many different possibilities. You’re always playing with, What does this mean? What does that moment mean? What does that look mean? You have to work fast, poetically, and have a good feeling for it to keep together the idea of who these people are. It’s generally always about the characters and the people, so far, and it doesn’t have to be. [It’s about] people in the audience watching people on the screen, as opposed to [watching] something else, like a nature film. It’s still a nature film, but it’s human nature. So those things start to tie together until you have a big mass of all kinds of interacting ideas, meanings, reasons for things, results for things, symbols for things. Filmmaking is sort of a collage medium.

“You have to work fast, poetically, and have a good feeling for it to keep together the idea of who these people are.”

Nick: I have just one more question for you, and it’s a question about much earlier in your career, one thing I was fascinated about when I was reading the book. What was your experience meeting Pasolini and Fellini? Was meeting both of those directors very early in your career influential to your perception of what a filmmaker is?

Gus: It was kind of a golden period for Italian cinema. We were able to go because our film teacher [knew] an American writer in Rome. So we could go over for six weeks and visit all the productions that were happening. Lina Wertmüller was shooting Seven Beauties, which is a classic. Fellini was shooting Casanova; he was sort of well into his career. Lina Wertmüller was at the beginning of her career. Pasolini was at the very end of his career; he died one month later. There were other filmmakers. They decided Antonioni would expect too much of us, so they didn’t bring us to him [laughs]. We spoke to a number of other filmmakers. We knew Fellini so well; for the past decade I had seen his films. First of all, going to Italy in general is like walking into a Fellini movie, which we didn’t know. As soon as you’re in Italy, you realize [how much] Fellini’s using all the stuff that’s within the life of the Italian community.

When we went to Pasolini’s house, it was very mysterious. He had built a very fancy ’50s-era interior in the ruins of a castle. So the ruins looked like there wasn’t anything there, but when you walked in, there was this great space. He asked each of us what we desired to do in cinema. We each had a little talk with him. In my case, I told him I wanted to be able to push cinema into the possibilities that I thought literature had reached. I didn’t see cinema going [there] yet. It came out sort of wrong, and I think he thought I wanted to transcribe literature or something [laughs]. But yeah, that was really great to be able to see them working. Fellini was at the set of Casanova, it was a nighttime shoot, and it involved the tallest woman in the world.

Nick: That must have been incredible, to witness that as a student.

Gus: Yeah, and she was near the director’s chairs. She had her own chair, because she was so big. She was from Ohio, so we could speak to her. She had no idea where she was or why she was there. There were 25 director’s chairs behind the camera, and people in each one of them. This happens a lot of the time in Italy. When you go to a film festival, there will be, like, a bishop, there will be a military person. They include all the people within the structure of their society. Everyone’s invited, so I think that’s probably what was going on. Someone explained to me that the people in the director’s chairs behind Fellini said, ‘Federico couldn’t shoot his movie without me!’ He spoke to Donald Sutherland; they were in a barn, and they were speaking to each other the entire time we were there. The whole time they were speaking, there was somebody explaining to us what was going on. They were saying that it was difficult because [Fellini and Sutherland] had differences in how to play the character, what the character should be doing, and how he should be doing it. You can see it in a film of the making of Casanova. It’s something you can find in cinema, these disagreements that linger on, and it was a lesson in what cinema might be like for us. You end up discussing things more than you actually shoot the film.