The artist reimagines Kelly's Princess Diana-approved designs as innovative sculptural works.

One day, while shopping at London’s Harvey Nichols back in 1987, Princess Diana cast her eyes upon a sequined leopard-print Patrick Kelly ensemble. “It’s too tight, isn’t it?” People magazine reported the Princess asked her male bodyguard. He gave the nod. “I’ll take it,” Diana decided, forever the rebel.

It was a testament to how far Kelly had traveled in his extraordinary life, charting a singular destiny that forever transformed high fashion, though he died before the world had the chance to receive the fullest expression of his gifts. But in the 35 years Kelly graced this earth, he created a life and legacy that resonates 30 years after his death.

As the first American and first black person to become a member of the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter in 1988, which governs the French ready-to-wear industry, Kelly brought the pop exuberance of Elsa Schiaparelli back to the runways of Paris Fashion Week. But Kelly’s sensibilities were formed in more modest beginnings: Vicksburg, Mississippi during Jim Crow. Born in 1954, Kelly’s father died when he was 15. He and his two brothers were raised by his mother Letha, aunt Bernard, and grandmother Ethel Rainey—who Kelly told People was “the backbone of my tastes.” When he was six, she showed him a fashion magazine. He immediately noticed there were no Black women in it. “Nobody has time to design for them,” she said. Kelly knew then exactly what he was born to do.

He kept it a secret, as he set forth, first accepting an art scholarship to Jackson State University, then leaving after 18 months to move to Atlanta, where Kelly started staging fashion shows. Pat Cleveland was one of his earliest clients, and she suggested he move to New York. He did just that, but the de facto racism of the North refused to make space for a Black gay man whose drive was unstoppable. In 1979 Cleveland anonymously purchased a one-way ticket to Paris for Kelly and he set forth into the next chapter of a journey that would bring him true love, recognition, and success. Kelly had finally achieved the American Dream—by moving to France.

Before Kelly died on New Year’s Day 1990, he was poised to reach new heights, having just signed a $5 million production deal with Warnaco. He was dressing Naomi Campbell, Grace Jones, Madonna, and Iman, embracing the beauty of all women with his designs. The designer’s extraordinary life and legacy are being honored in Derrick Adams: Patrick Kelly, the Journey at SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film in Atlanta, a dialogue between artists that explores the links between fashion and the Black experience.

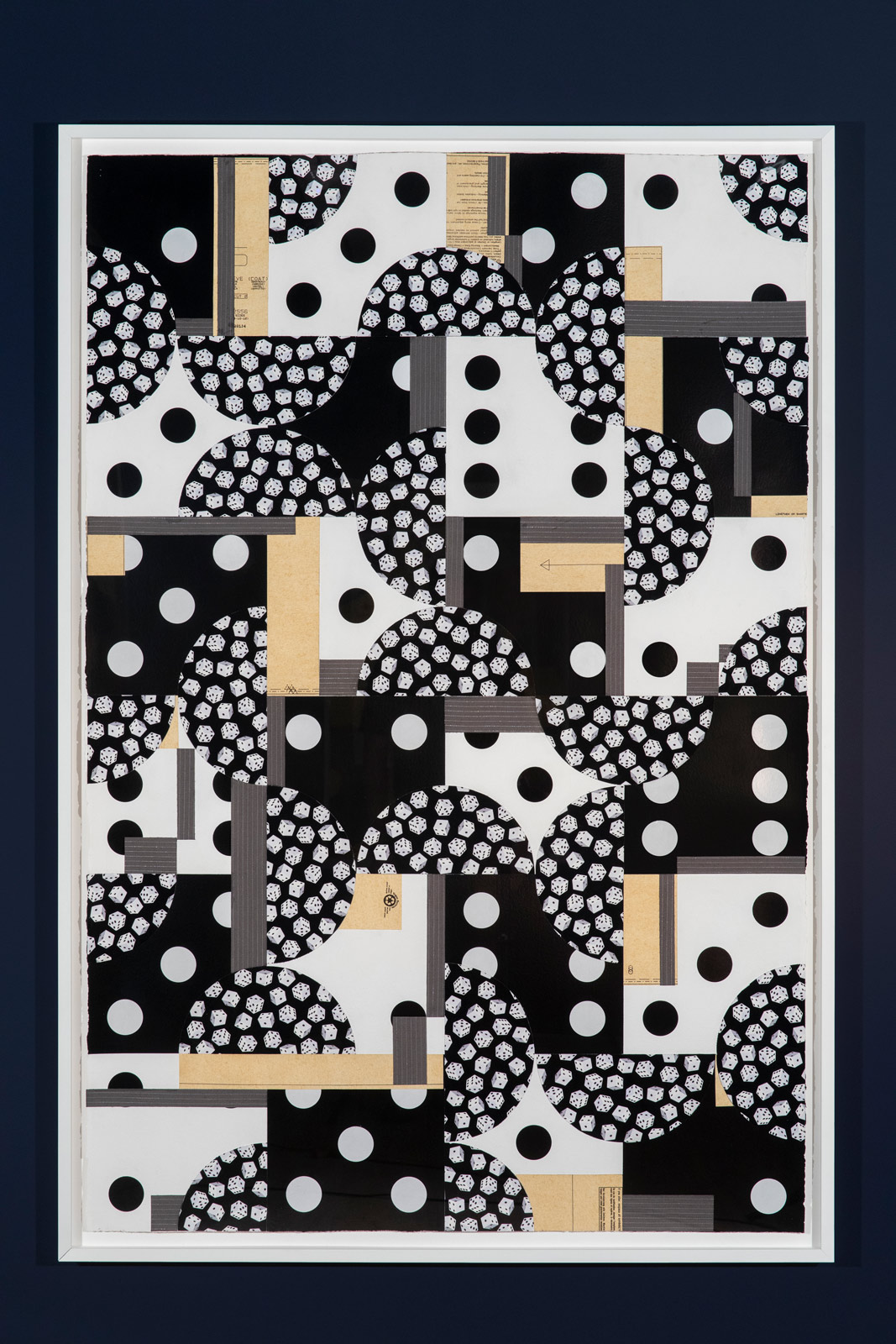

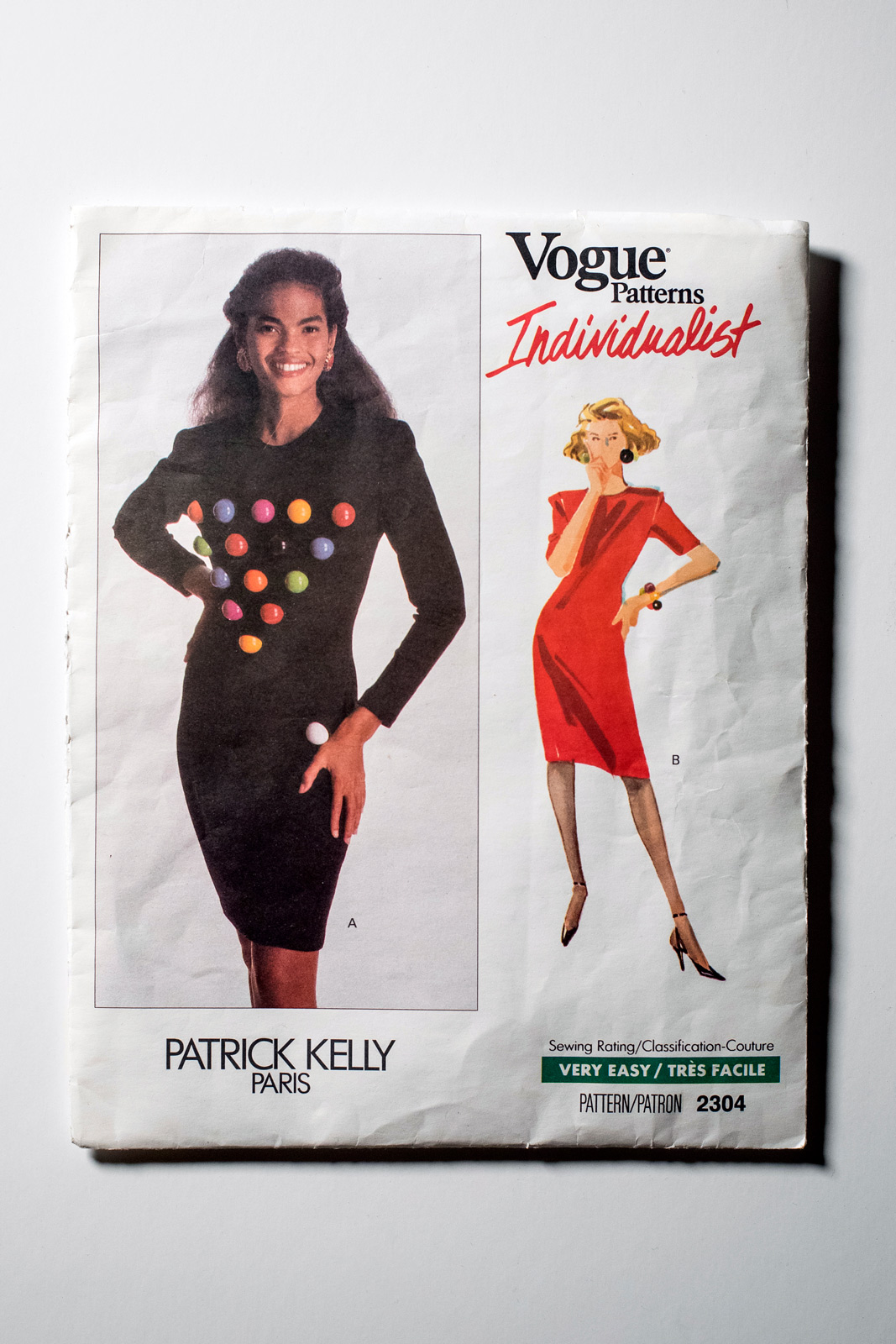

The exhibition brings together a selection of Adams‘s that he calls “mood boards” and sculptural works that incorporate Kelly’s vintage clothing patterns, iconic fabrics, bold and colorful geometric forms, and embellishments alongside Patrick Kelly garments, accessories, fashion show invitations, newspaper clippings, and photographs on loan from the personal collection of former model Carol Martin, Kelly’s lifelong friend who first met him in Atlanta in the 1970s.

To prepare for the exhibition, Adams immersed himself in the Patrick Kelly archive at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York, where he discovered a trove of correspondence, sketches, swatches, photographs, and other memorabilia, including a proposal for a book about Kelly’s life written by his friend, the esteemed poet Maya Angelou—which inspired the title of the exhibition.

“I thought it was important to reference her title of the book in the title of the exhibition because it talked about his life in just that one phrase (‘The Journey’),” Adams says. “He traveled from Atlanta to New York to Paris, and back and forth. He had all these different networks: the South, the North. The language and the symbolism are very reflective of those regions.”

Adams’s art allows us to stop and pause, to consider broader themes in Kelly’s work such as color theory, racial identity, and texture, and what they mean to different people based on their geography. There is an intentionality, and a specificity to Kelly’s work that underscores the pleasure it brings—it is both bold and playful, subversive and meaningful. Kelly used fashion to celebrate, honor, and reclaim the vibrant joy and graceful dignity of Black women from a world that tries to tear them down every day. He took his grandmother’s penchant for using odd buttons in a festive manner when repairing garments to the ultimate height, making them a signature part of his aesthetic along with lavish bows and bold prints.

But it was his daring to confront the ugly specter of racism and subvert it that transformed his work into a political act. He took images of Aunt Jemima, Josephine Baker’s banana skirt, watermelon wedges, Black baby dolls, and golliwogs as mascots, seeking to remove the stigma in the same way that Black culture has embraced the “n” word. At a time when no one in fashion was talking about race, Kelly centered it on the runway, daring the world to look away. Though it was provocative, he did it with love.

It was a sentiment that came forth not only in his designs, but in the way Kelly carried himself. “My earliest memories of Patrick were through magazine imagery… seeing a young Black man on the cover of a magazine wearing something other than a suit,” Adams says. “Although he was surrounded by models and people who were more lavishly dressed, he was pretty casual in his presentation. But he was still the center of attention. That gave me a sense of liberation. He definitely influenced my self-perspective.”

Kelly, in his trademark denim overalls and bicycle hat, would always spray paint a large heart on his fashion week stage set. It was a symbol of love that marked the hand of the artist in everything he did. When he died at the tender after of 35 from AIDS, he left a legacy that resonates even more powerfully today with his fearless acts of self-love, his dazzling sense of wit, and his determination to find beauty and joy in everything he touched.

Derrick Adams: Patrick Kelly, the Journey is on view at the SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion and Film in Atlanta through July 19, 2020.