Meet the photographers who captured Salt-n-Pepa before they got a record deal and Public Enemy's first trip to London.

The exact dates that bookend the pinnacle of hip hop are highly debated. Some claim the ’90s to be hip hop’s finest era, citing the explosive careers of legends like Tupac and Biggie, while rap purists would cite the genre’s founders of the 1980s. Others may assert that we are currently living in rap’s golden years. Getty Images curator Shawn Waldron set aside his personal affinity for what the ’90s offered with groups like A Tribe Called Quest, and focused on the formative years of the genre, between 1981 and 1993, for Beat Positive, an exhibition that is currently on show in New York at 10 Corso Como through February 2, 2020.

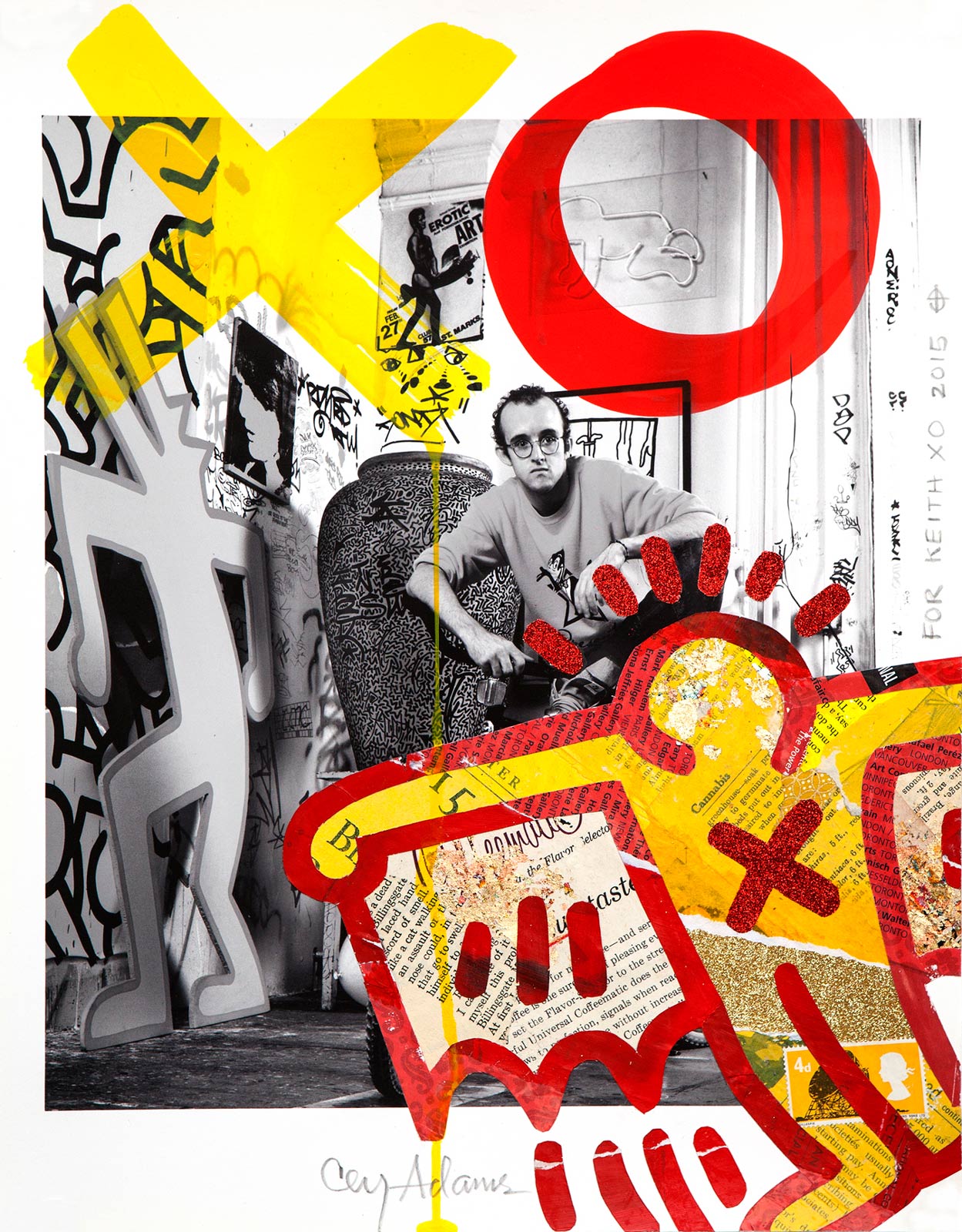

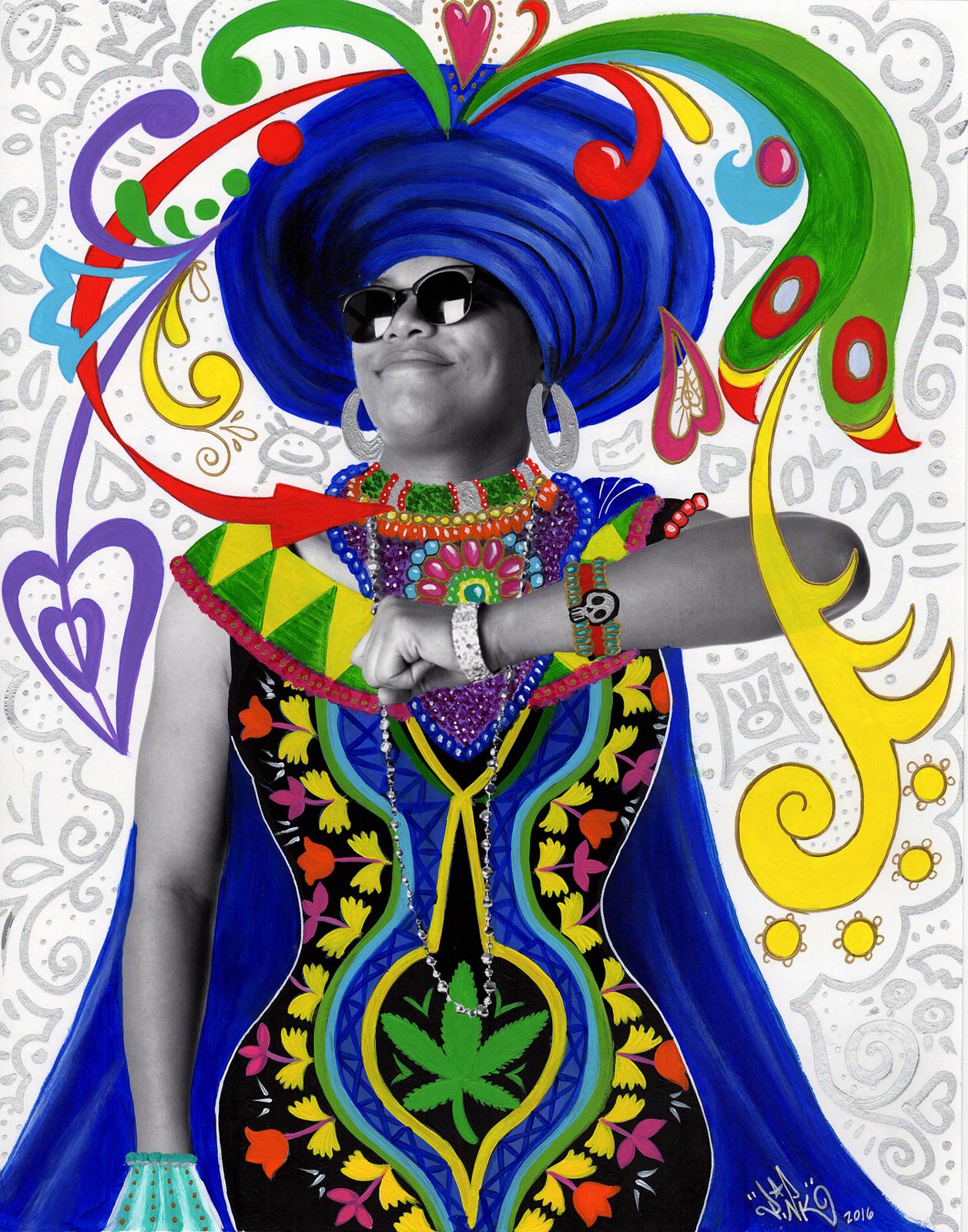

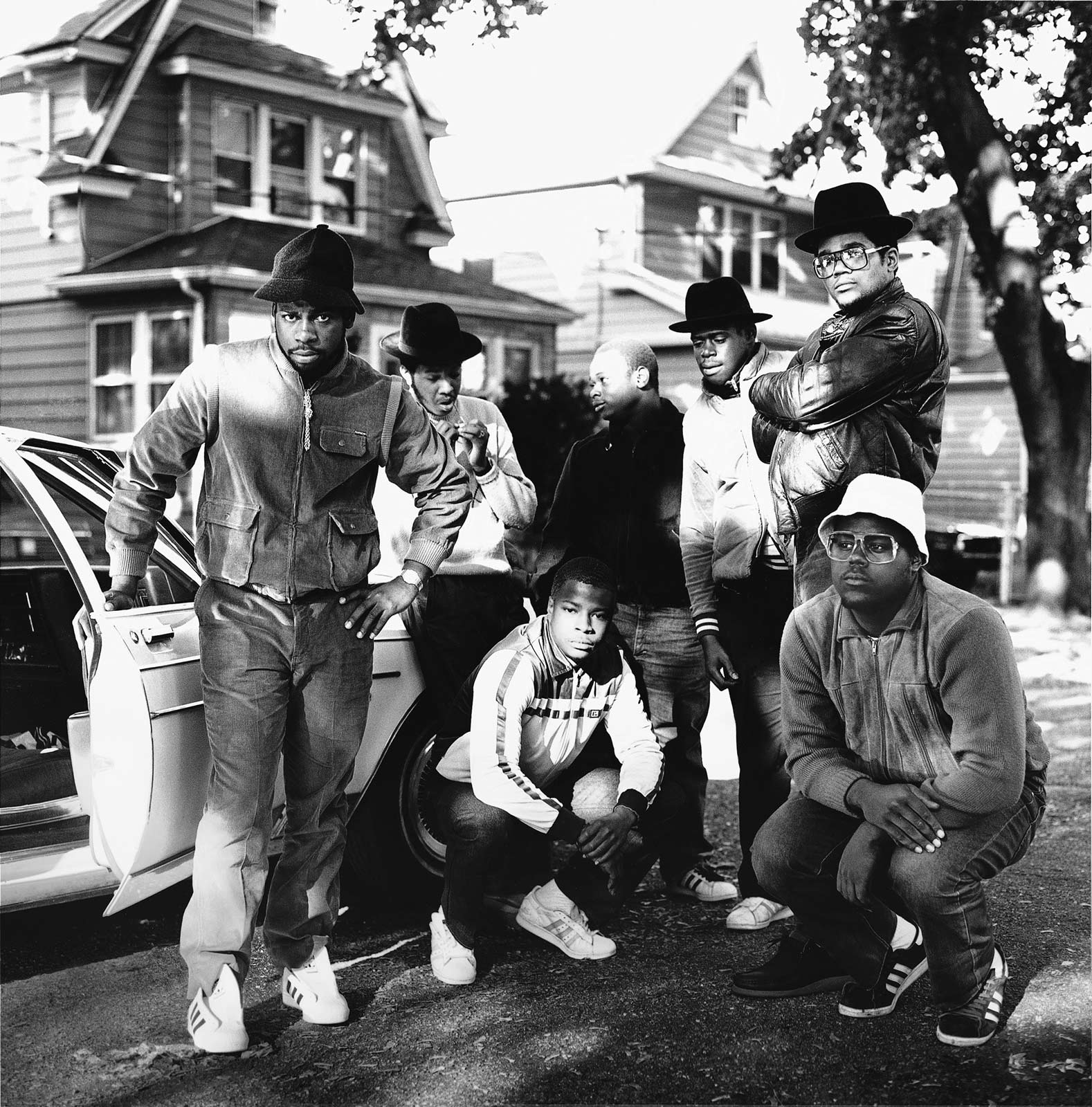

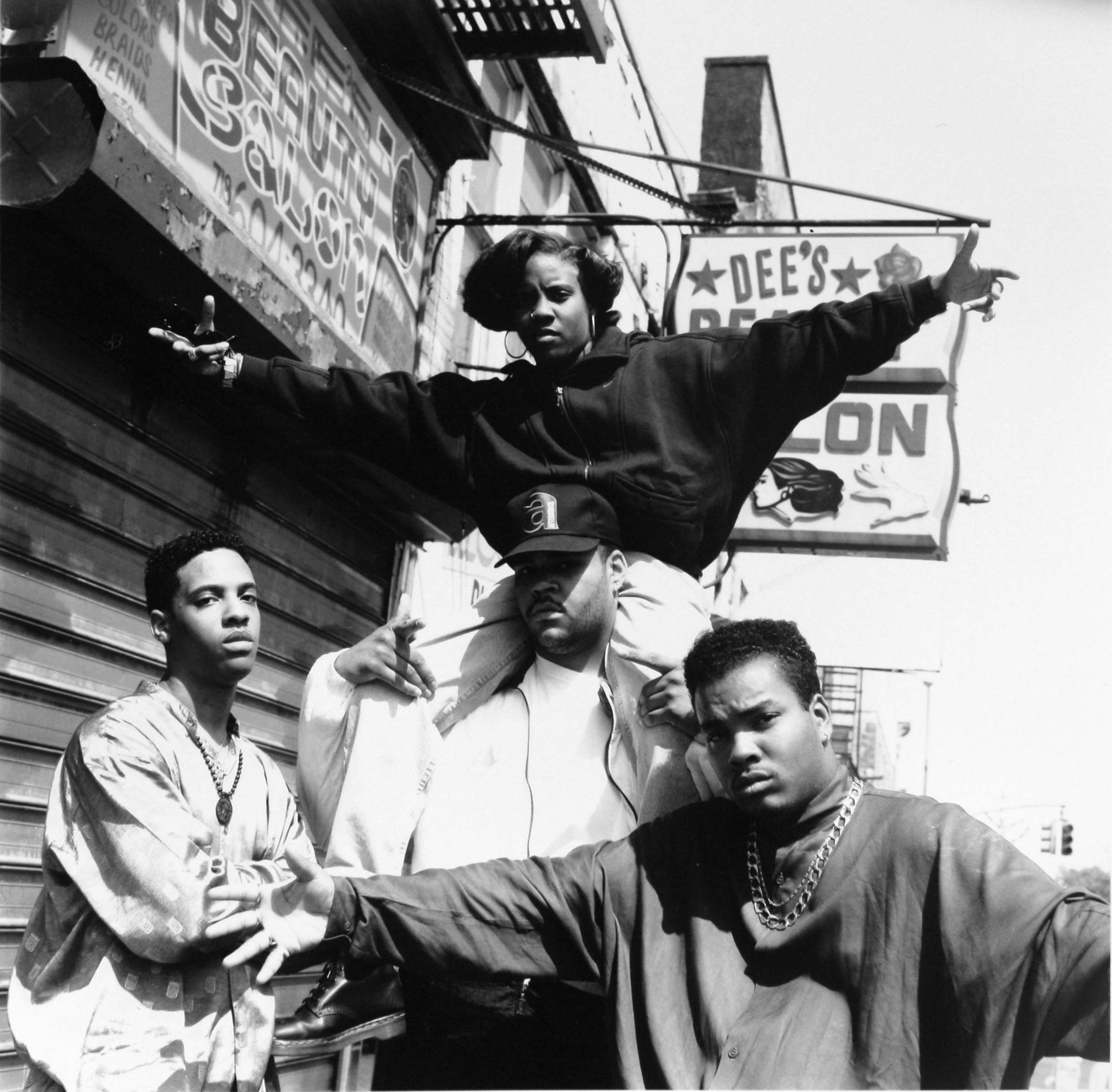

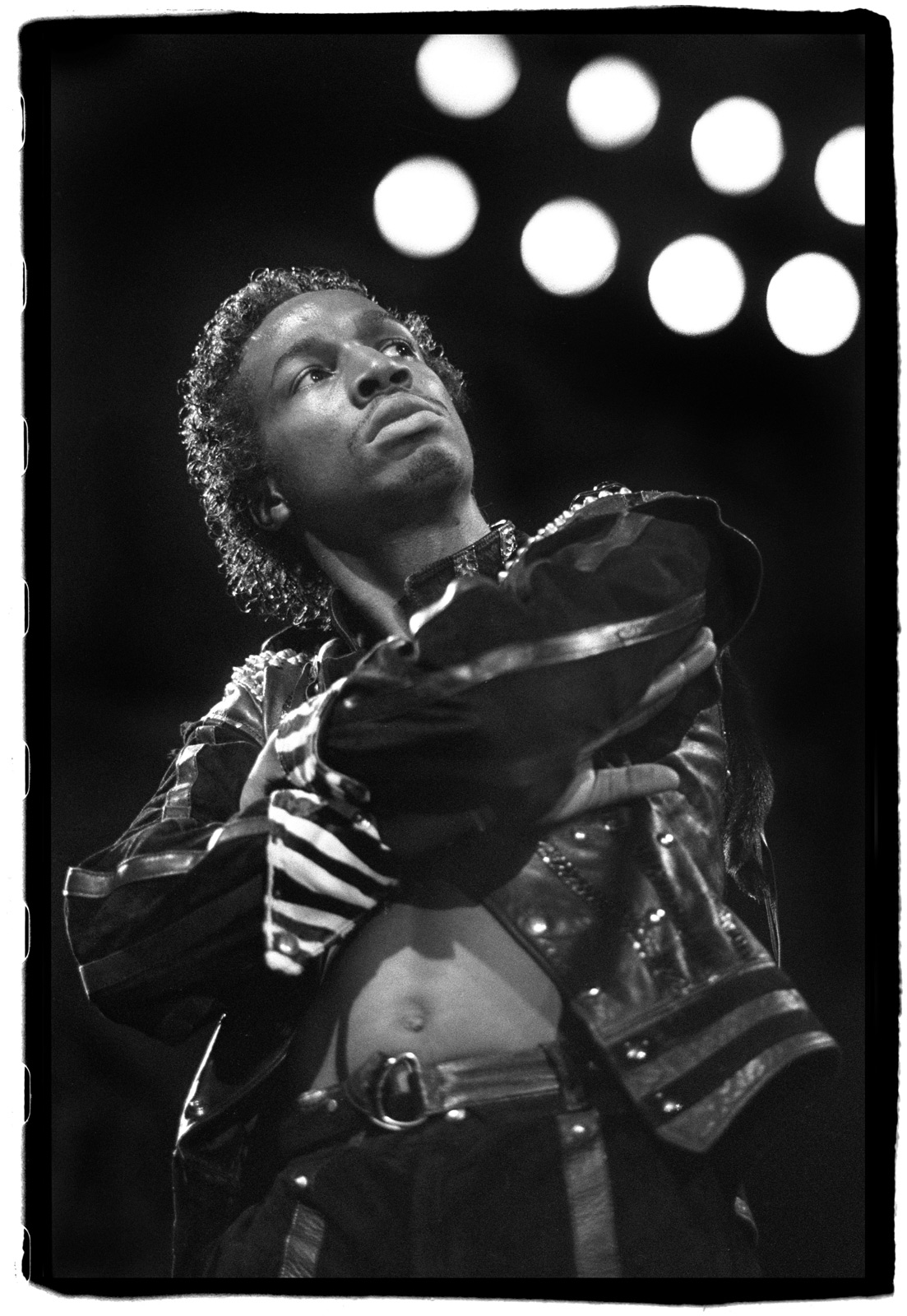

Featured alongside a collection of unseen images from the Getty archives are iconic pictures by photographers Janette Beckman and David Corio. Janette and David are responsible for some of the most influential photographs of the golden era of hip hop. Both are originally from England, and entered the rap scene during its infancy in New York, capturing then-unknown artists and moguls who would become some of the most iconic in hip hop history. Lauded for intimate documentation of the vibrant blossoming rap scene, Janette and David have shot everyone from LL Cool J to Public Enemy—Salt-N-Pepa to Eric B. & Rakim.

Document spoke to Janette, David, and Shawn about the importance of celebrating the early years of hip hop, witnessing London’s first hip hop show, and shooting some of the genre’s biggest stars.

Document Journal: How did you get involved in the hip hop scene in New York?

Janette Beckman: I was a photographer working for Melody Maker which was a weekly music magazine in London, and I had been photographing all the punk and British youth culture stuff. I’d been working for [Melody Maker] since 1976, and in 1982 I was at a meeting, and they’re like, ‘There’s this hip hop tour coming to London, do you want to go photograph it?’ It was the first time we’d really been exposed to hip hop. They gave me the address of a seedy hotel behind Victoria Station, I went down there with my camera in the afternoon, and there were just all these amazing-looking people down there. Punk at this point in London was dreary and dark, people wearing leather and all in black. I get to this hotel and there’s all these really vibrant-looking people, dressed completely differently. I just started photographing everybody that I saw, I had no idea who they were. I went to the show in the evening—

Document: Who was performing at that show?

Janette: It was crazy. At that show they had graffiti artists drawing on the backdrop live, they had Grandmixer D.ST, they had Afrika Bambaataa, they had Fab 5 Freddy, Futura, Don D, Rock Steady Crew, the double-dutch girls—there were so many of what turned out to be icons of the culture. I had photographed them all in the afternoon not knowing who they were. It was just an amazingly mind-blowing experience, sort of a renaissance moment for me. I ended up staying here because all of the things that were in that show were happening [here]—graffiti, people breakdancing on a little piece of cardboard in the street. It was just great.

David Corio: There’s one picture in [the exhibition] of a guy breakdancing on his head, and that was [my earliest memory of being inside the hip hop scene]. I had just come over here on holiday and it was like Sunday morning, I was walking up the West Side Highway, and just heard this music coming out of the club, midday on a Sunday. It wasn’t properly open, it was just these guys breakdancing, practicing their moves. [I was] just looking at the [negatives] again a couple of weeks ago, there’s Grandmixer D.ST who was breakdancing as well. That first show in London was the real groundbreaking one. It was the whole mix, as well, it was the graffiti, the double-dutch skippers, break dancing, and it’s like, ‘Fuck me, this is totally mad.’ I don’t think anyone realized it would be big. It was like, this is great, but it’s just going to fizzle out in a year or two, [we] didn’t really know at the time.

Document: Did you feel welcomed into the scene?

Janette: Everyone was totally friendly, nice, and happy that I was actually interested in what they were doing.

David: I was in London and I was shooting mainly for magazines and newspapers. The usual run of things would be, journalist does the interview, then the photographer’s got five minutes. So I normally dragged [the artists] out on to the streets. It was often the first time that they had traveled abroad. So they were just blown away by England, London particularly. Public Enemy—their first morning in London, it was a foggy morning, which isn’t really typical, but it was trademark London. Chuck D came over and said, ‘We drove in from Heathrow Airport and we haven’t seen any McDonalds.’ You won’t starve, don’t worry, there are burger joints in London [laughs]. There was a sort of freshness, I guess, an innocence—a band like that can look hard and militant and whatever, but they were very laid-back.

Document: How did your work shooting punks and reggae artists—how was that different than shooting hip hop artists in this new genre?

Janette: The hip hop people were more energized. They had more attitude and style. The punks, by the time the early ’80s came along, they were a little worn out. But in a way they’re very similar because both of those cultures come from really bad economic circumstances. London was pretty broke when punk came, New York was broke when hip hop started. Kids didn’t have a chance to get a job, they didn’t have a future, and so they started doing this, they wanted to tell people about their lives and what was going on. They didn’t have money, there were no stylists, they’d have to go get clothes from their mom’s closet and cut them up, or get stuff off the street, or from someone like Dapper Dan for instance.

David: I was doing a lot of reggae stuff in England, and it was very similar to hip jop in that you can guarantee that [the artists] would be at least an hour late [laughs]. So I was well prepared for hip hop as well, you can get there on time—It’s a good opportunity to suss out locations, ‘cause you can guarantee that they would [arrive] at least an hour or two after the designated time. I think that hip hop and reggae have a lot of links and similarities anyways—Eric B. & Rakim are both of Jamaican descent. That influence goes through into hip hop, I think. The language I found, and trying to keep up with hip hopI was never in with all of the vocabulary and such. I went in a minibus with De La Soul from downtown up to Harlem—I couldn’t understand a word that they were saying–it was like some new language that was beyond me [laughs].

Shawn: And even then the language was totally localized—there was different slang coming out of Queensbridge than what would come [out of] Brooklyn, that would come out of the Bronx. The whole culture hadn’t grown together yet, it was still sort of in these pockets. It was at the point where it was happening, but even if you think about the bridges, and those neighborhood battles—ow you get city to city or label to label, posse to posse, but then it was still hyperlocal in terms of New York City.

Document: Putting you both on the spot now—from this era, who was your favorite to shoot and who was the most difficult to shoot?

Janette: I did a lot of shoots for Salt-N-Pepa—I shot them before they had a record [deal], and it was actually just Salt and Pepa, no Spinderella; just us hanging around on the street on the Lower East Side, three women having a good time. They were dancing in front of the mural, I’m taking pictures, we go to the deli—It was a hot day—we get ice creams. And then I did their record cover, then I did another record cover for them, then I did another…So I have a soft spot in my heart for them. I don’t have a worst person from hip hop. I have a worst person, worst shoot from other celebrities that have been really annoying, I could mention them—

David: Oh, go ahead.

Janette: Bill Cosby, who I was shooting for Nickelodeon in the ‘90s. It was a team of women. He kept us waiting for four hours in a studio, and it was Friday, a hot summer, everybody wanted to go and get their weekend started, and he was just there chatting with his friend, he wasn’t doing anything. He comes over, and he’d already approved his pose, which had been hand-drawn out. You call him Dr. Cosby—’Hi Dr. Cosby, here’s your pose.’ And he just looked at me and he goes, ‘I don’t think I’m going to do that.’ I literally took 10 shots and that’s all he would [allow]—we’d been there for four hours, and it was somewhere way up in Queens, and then he was just like, ‘I’m done.’ He was really awkward and rude. And now…

But all the hip hop people that you’d expect to be [difficult]—’How was NWA?’ They were great. ‘How was Public Enemy?’ Great.

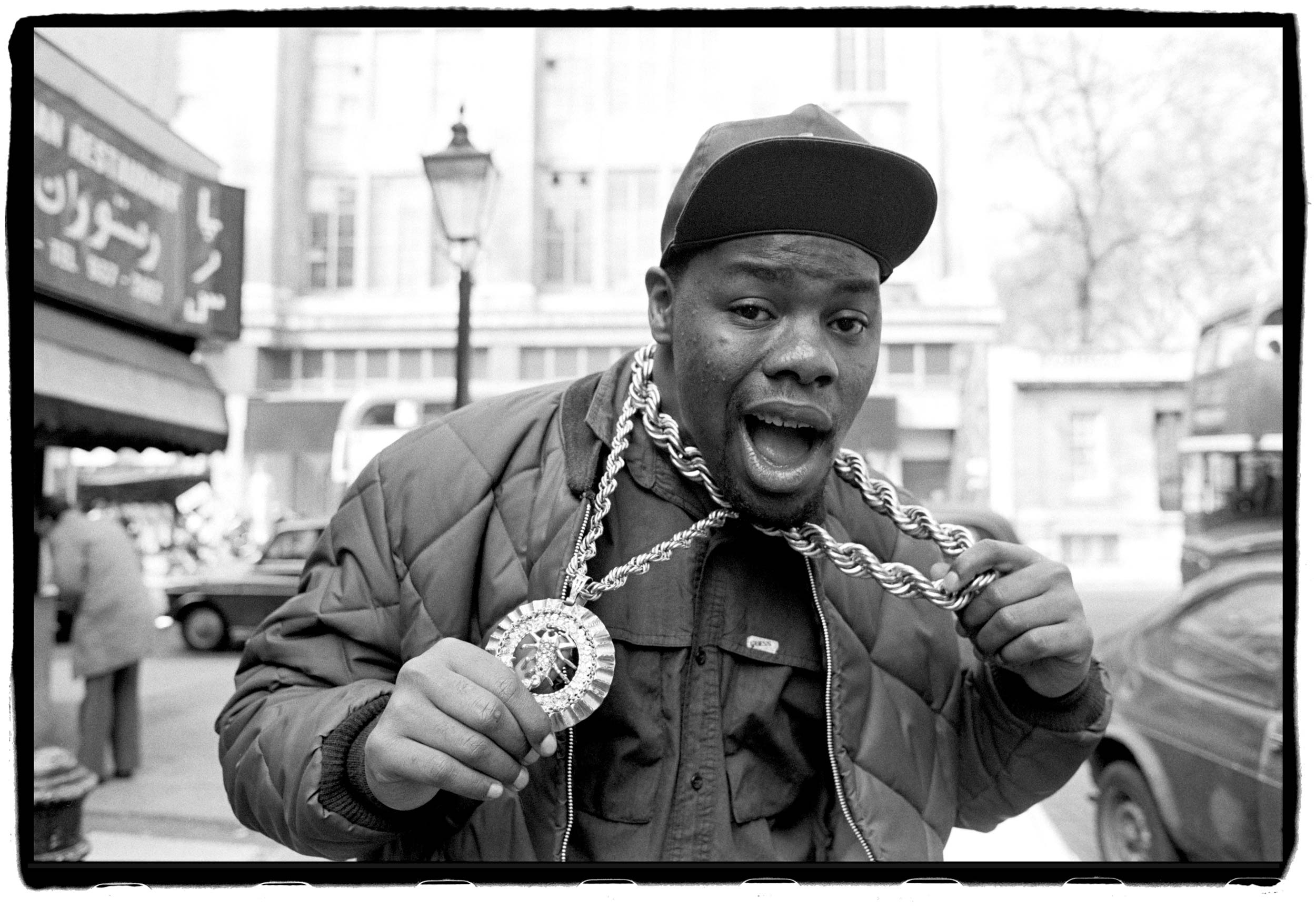

David: I would say Biz Markie from this shoot, he was just—you can’t get a bad picture of him. I took Biz to the street, he immediately just ran over, jumped on top of a Mercedes that was parked there, and was jumping up and down on the hood. I took a couple of pictures, and he jumped off, and I took a couple more pictures like that. Every shot, his face right in the lens, sticking his tongue out, pulling the chains. I didn’t need to speak. When you have people like that it’s great. Of bad people—Eric B. I got good pictures, but he didn’t say a word and he didn’t move an inch the whole shoot. I shot about three, four rolls. Rakim was moving around, it was in a hotel room—[Eric B.] just sat there. He didn’t blink. The pictures came out alright, but it would have been nice to have a bit more variety [laughs]. I was moving around him. Sometimes you just can’t break through. With him there was a wall there—you couldn’t penetrate it at all.

Document: Shawn, what’s important about putting this show on right now?

Shawn: This all started when Phife from A Tribe Called Quest died. Tribe was my band, that’s the one that I loved, that I grew up with, and when he died it rocked everyone in the hip hop world a little bit. That’s what made me really go back and look at this era again and listen to the music again, and then really thinking [that] this would be a great show. The style is so different, the lyrics and what people were talking about back then, that’s why [the show] is called Beat Positive—this idea of being positive, and consciousness, and all that that was happening and was filtering through the music then. Then it was a rap game, now it’s a business. That’s why [the show] is very specific about the years, that’s why it ends in ’93, is because that’s the tipping point where [hip hop] exploded and you get Biggie and Tupac, Wu Tang, Nas—it becomes monstrous, big. You get lawyers involved, and there’s a lot of money, and the major labels. Now you’re coming back around in hip hop, and I wanted to focus on, ‘This is the origin, this is where it started.’

“Beat Positive” is on view through February 2, 2020 at 10 Corso Como in New York City. On Friday, December 13 the exhibition space will host a panel with Janette Beckman, Dapper Dan, Vikki Tobak, April Walker, Va$htie, and more.