The 16mm short film investigates the relationship between color, cosmetics, and social capital

In Ancient Egypt, color was considered an essential part of an item or person’s nature—so much so, that the Egyptian word “iwen” was used interchangeably to mean appearance, character, or being. Through the symbolic application of color, they imbued their art, clothing, and jewelry with a deeper layer of meaning that could be interpreted according to the object’s hue. While the evolution of these systems varies among different cultures and time periods, the widespread use of color as nonverbal social code helped cement the legacy of dye and other colorants as one of the most highly valued trade goods in the ancient world.

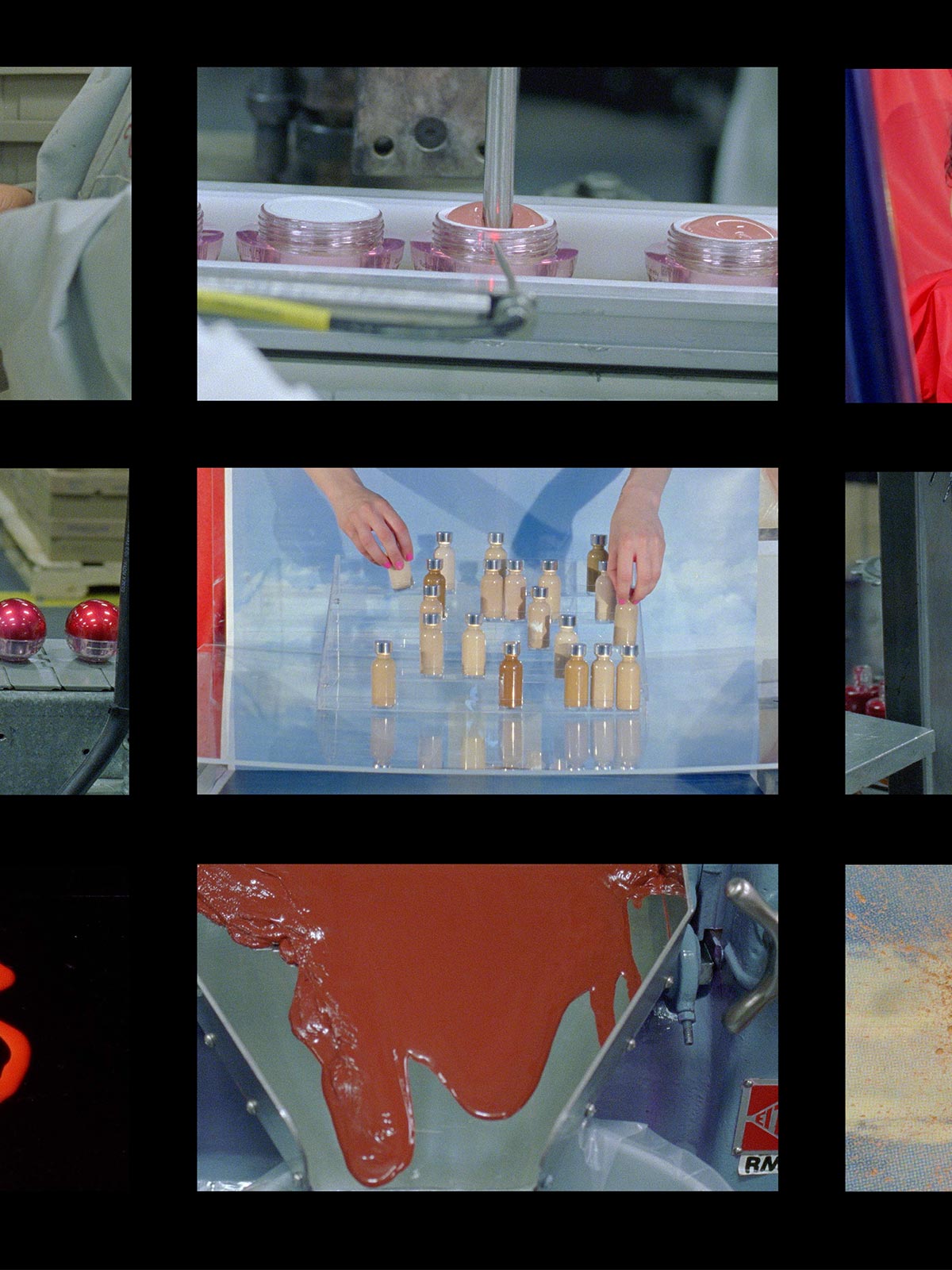

Canadian-born artist Sara Cwynar investigates the relationship between color, cosmetics, and social capital in her 16mm short film Covergirl (2018). Currently on view at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, the film mixes footage shot within the artist’s studio and in an undisclosed makeup factory, punctuated with shots of flowers, red lips, and dripping colorants. Images accumulate and dissolve, producing a peculiar flattening of signal power; as with her representative works, Cwynar’s expert manipulation of pop culture imagery serves to collapse the distance between cultures old and new, high and low, unfamiliar and cliché.

The focus of Covergirl alternates between the factory floor and studio footage of Cwynar’s friend and longtime muse, Tracy. In a 2018 interview with Aperture, Cwynar remarks that she picked Tracy as a sitter because “she poses kind of ironically, with the knowledge of a history of representations of women in mind.” We watch as she carefully applies lipstick, shifts in glossy red shoes, reclines on the couch like an odalisque. Yet even as she performs the gestures of feminine deference, there is a sense of barely contained subterfuge: her image courts the gaze, while her confrontational glance condemns it.

All the while, the narrator’s voice—a combination of the artist’s plus male and female voice actors—maintains a staccato quality even as it speaks over itself. The auditory overlap mimics the symbolic density of Cwynar’s visual landscape, juxtaposing the aesthetic of consumerism with the contributions of dominant cultural theorists as quotes from Ludwig Wittgenstein, Frantz Fanon, Henri Matisse, David Batchelor, Kathy Peiss, and Susan Stewart comingle with the artist’s wry observations about everything from the ontological perception of color—“the essential thing about private experience is really not that each person experiences her own color, but that nobody knows whether other people have [this or] something else”—to its complicated relationship with social status—“The taste for color costs many sacrifices.”

Before the advent of synthetic dyes, the market value of a color was determined by the difficulty of its production. To harvest Tyrian purple, marine snails were boiled for days in giant vats to produce a single kilo of the famed hue, with thousands of shells and countless hours of labor required to color even the trim of a single garment. This turned purple-dyed textiles into elite status symbols ruled by sumptuary laws, and by the fourth century AD, Tyrian purple was so closely regulated in Rome that the emperor was the only person permitted to wear it.

Though purple came to be seen as a symbol of elite status—it would clothe many a king, noble, priest, and magistrate—the use of color as a class signifier extends far beyond the singular shade. As Philip Ball describes it, “Medieval and Renaissance cultures were virtually color-coded hierarchies. Crimson and scarlet garments were for cardinals, bishops, popes, and monarchs, echoing the ruby-purple of the emperor’s robes in classical Rome. Clothing displaying other rich colors was a mark of wealth; black in particular came to signify the conspicuous consumption of the affluent merchants, who could afford cloth dyed in several expensive dyes until it took on this somber shade.”

The advent of new dyes marked a major transformation in value, and black—notoriously expensive to produce throughout the 16th century—suddenly became accessible to the masses. By the 19th century, it had been adopted as a standard uniform color for service professions, including the shopgirls who staffed retail shop floors, fully entering into the cultural mainstream with the introduction of Chanel’s little black dress in 1926 (in The Atlantic, Shelley Puhak describes how shopgirl style was later co-opted by the upper classes as a symbol of modern ease, bringing the color’s evolving class associations full circle.)

Not limited to the textile trade, the use of color to denote class differences is a common feature of many ancient cosmetic traditions. In 3000 B.C. China, men and women stained their fingernails with substances like gum arabic, gelatin, beeswax, and egg to produce a class-based color code, with only Chou dynasty royals permitted to wear gold and silver (while subsequent royals could wear black or red, the lower classes were, predictably, forbidden from coloring their nails at all.) When pale skin came to be seen as a marker of aristocratic status, white powder and lead paint were used to mimic the look of one who could afford leisure time indoors. In the 18th century, women would bleed themselves to induce a white-ish cast, whereas society women in Elizabethan England took to wearing egg whites on their faces in pursuit of a paler complexion.

Though we may not bathe in milk like Cleopatra, today’s women still manipulate our natural skin tone with chemicals to attain an even, plump, and poreless complexion—which constitutes a class signifier in and of itself, as Amanda Mull described in The Atlantic. Studies show that the average woman uses between nine and 15 personal care products per day, and with the typical product containing anything from 15-50 ingredients, researchers have estimated that with the combined use of cosmetics and perfumes, women place around 515 individual chemicals on their skin each day. The intersection of color and class association is also informed by a racist history that pervades the language of cosmetics advertising. (For example, even the most innocuous moisturizers claim to affect a brighter—and lighter—complexion; meanwhile, skin bleaching products retain a global market despite toxic or unknown safety profiles.)

“Most of our information on makeup comes from a hostile tradition, written by men regarding women,” states Cwynar, over footage of cosmetics being automatically dispensed and packaged on an assembly line. The mechanized production and distribution of makeup products calls to mind the manner in which beauty standards are socially disseminated throughout a culture. Deemed “the noblest of the senses,” the role of vision is especially dominant in Western thought; this makes it easy to forget the brunt of societal forces involved in fostering the desire for beauty, which is in many ways commensurate with other forms of success and social status. As Cwynar puts it, “In order to achieve [that success], whether it be mental, physical, financial, or social, one has to be looked at by everyone with whom one comes into contact.”

Covergirl is part of Sara Cwynar’s exhibition Gilded Age, on view at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut through November 10th.