Yuskavage's paintings of nude women and partially clothed girls have raised eyebrows for their perceived carnality. But her subjects never asked you to stare at them.

For an artist whose alluring paintings sell for somewhere in the mid-six figures and have fetched over $1 million at auction, Lisa Yuskavage is quite humble. “Being an artist, you’re not that famous,” she said recently on the terrace of The Little Nell in Aspen. “I don’t think a lot of people recognize that, but I do.” Yuskavage was in Colorado to receive the 2019 Aspen Award for Art from the Aspen Art Museum, where she’ll have an exhibition of landscapes titled Wilderness February 15, 2020 to May 31, 2020.

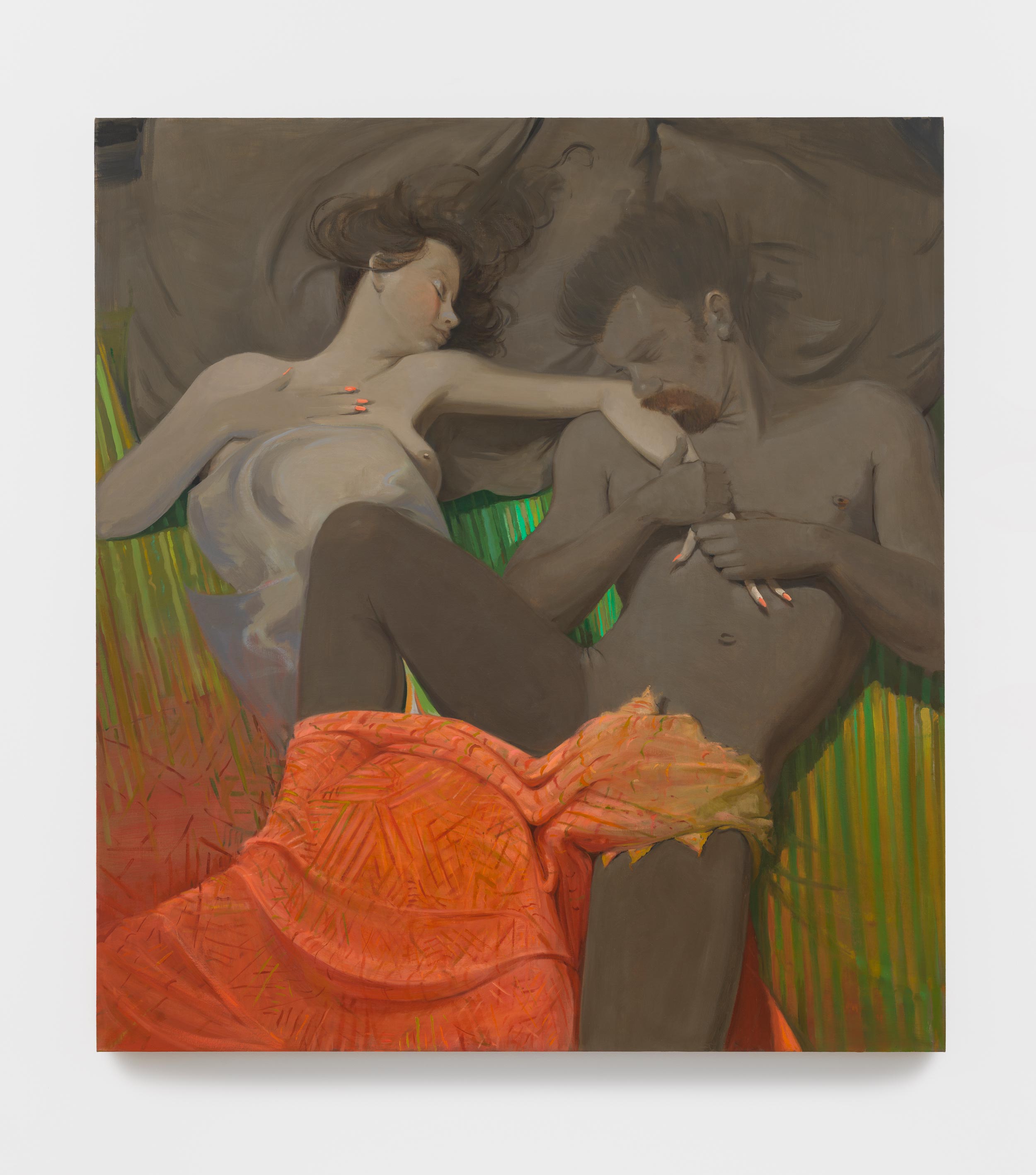

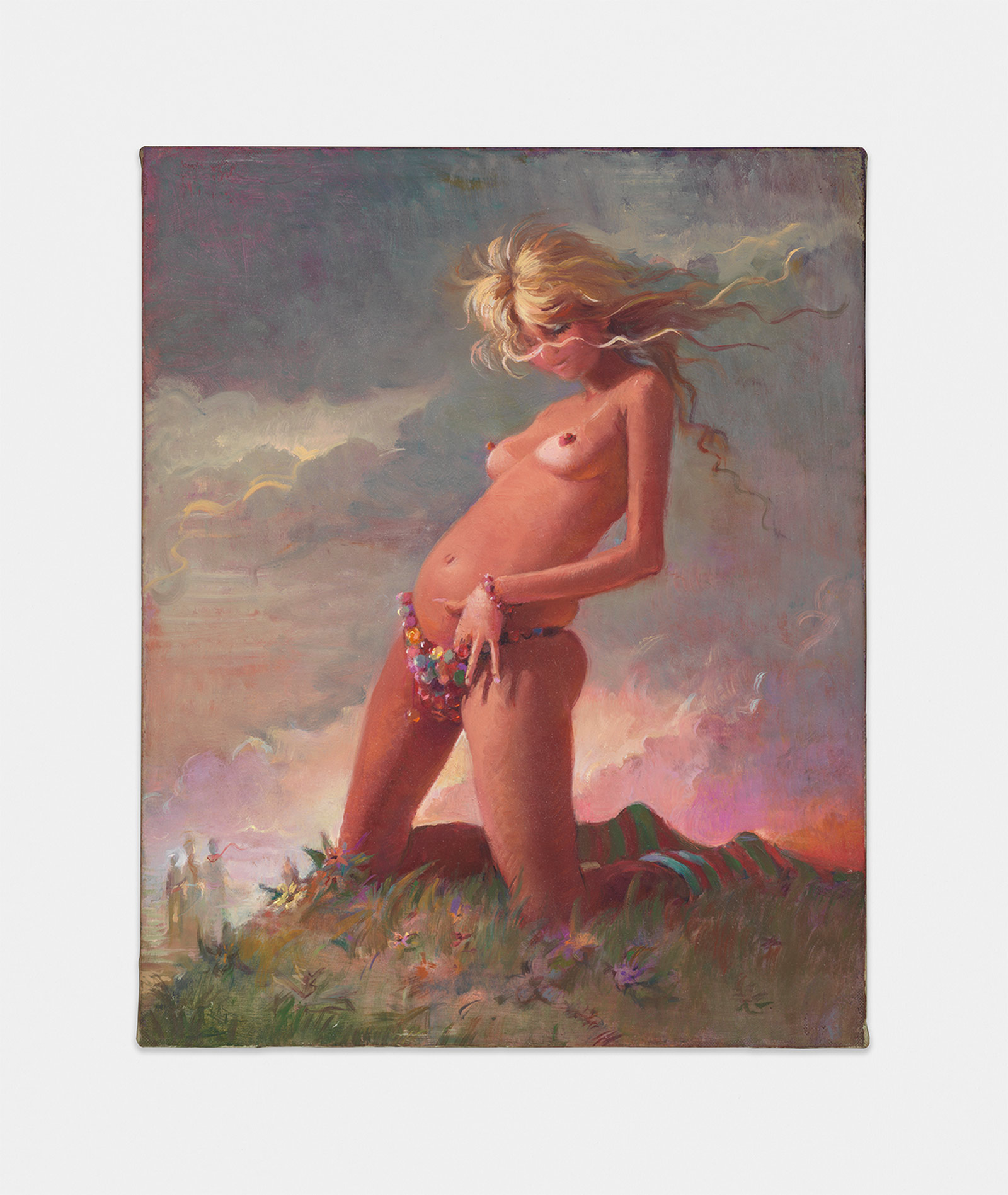

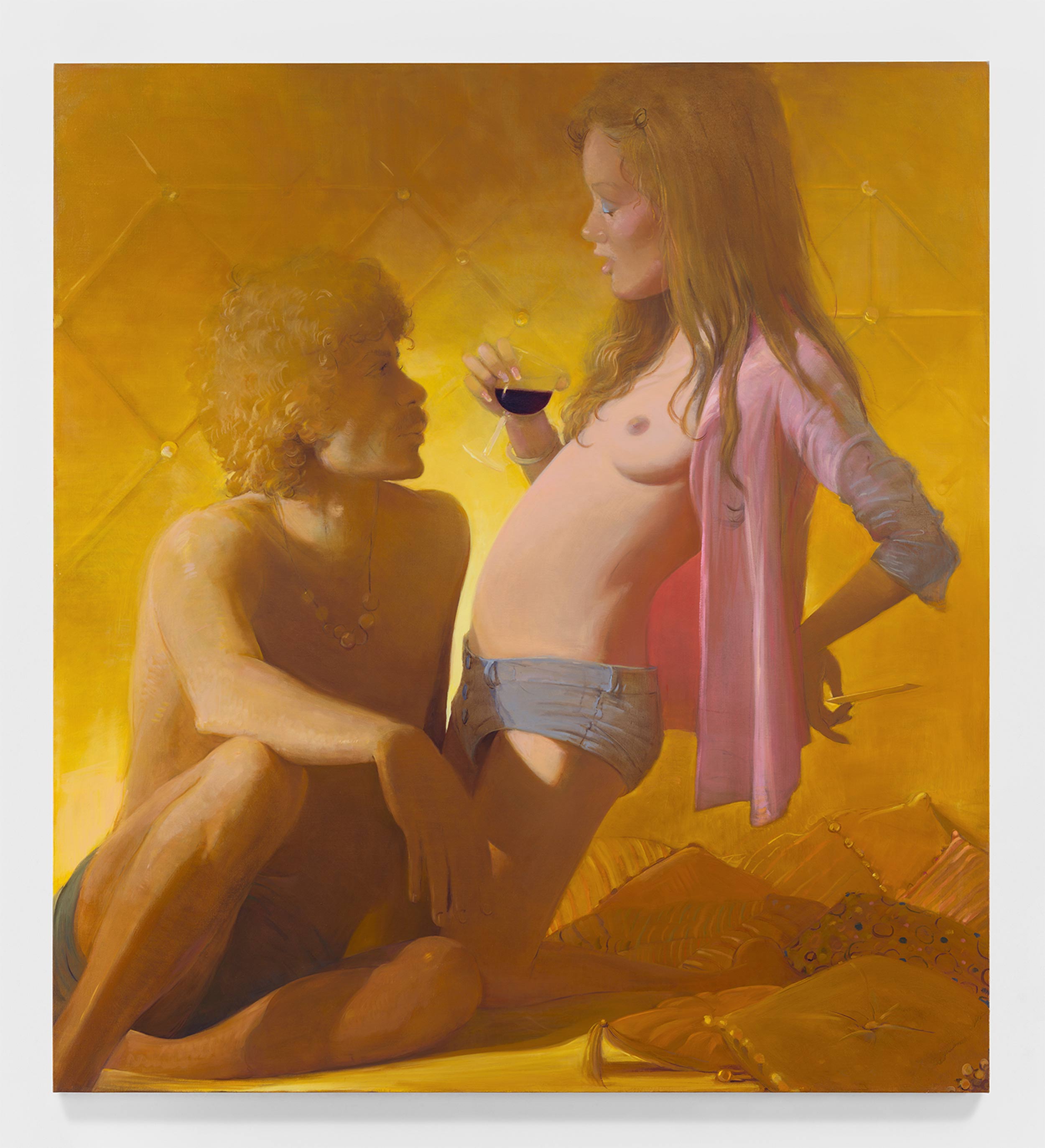

For over three decades, Yuskavage’s magical, provocative paintings of nude women (and to a lesser extent, men) have raised the eyebrows of the more conservative ilk for their perceived carnality. A naked woman sits, legs spread wide open to reveal a hairless vagina in a 1995 painting titled Rorschach Blot. In another, a clothed woman holds a naked older woman, growing out of the landscape. A naked man sits on the lap of his nude lover, sipping a glass of merlot as she wraps her arms around his waist. Make no mistake—Yuskavage isn’t trying to portray these women as particularly sexual, she’s simply allowing the women in her paintings to just “be”. Document sat with the artist to discuss the power of provocation, the roles of masculinity and femininity in her paintings, and why only smart people understand her work.

Ann Binlot—What are you working on at the moment in your studio?

Lisa Yuskavage—I actually am making a painting that’s going to be in this upcoming show for the Aspen Art Museum in the spring. This particular show is a show of landscape paintings, but this is a painting of a nude in an interior, and there is a landscape painting on the wall. So it’s a bit of a play on the idea of a landscape painting. Most of these paintings are figures in landscapes, literally. But this painting is not taking place in a landscape. It’s taking place in an interior. The landscape hanging on the wall is one of my paintings.

Ann—That’s so meta.

Lisa—It’s very meta.

Ann—Sexuality is a big theme in your work. What drew you to it at the beginning of your career?

Lisa—I don’t know if sexuality…that’s your take.

Ann—That is my take.

Lisa—I could say shame or awkwardness because if you put somebody naked, to me, what I see is maybe somebody else. When you take somebody’s clothes off, the subject seems to be awkwardness, or something else. That’s what I always thought I was doing. Other people saw something else.

Ann—Why did you undress your figures?

Lisa—That’s the biggest subject in the history of art. In a way, as a woman, I didn’t want to not have the opportunity to do the thing that was the largest historical opportunity, and to enter that historical opportunity, which is paint—they weren’t always undressed. There have been many costumed figures, but those aren’t always the ones that people seem to remember.

Ann—Are you trying to strip away that awkwardness that you speak of when you—

Lisa—Clothe them? Not necessarily. They’re pretty awkward even in their clothes.

Ann—Why do you portray awkwardness?

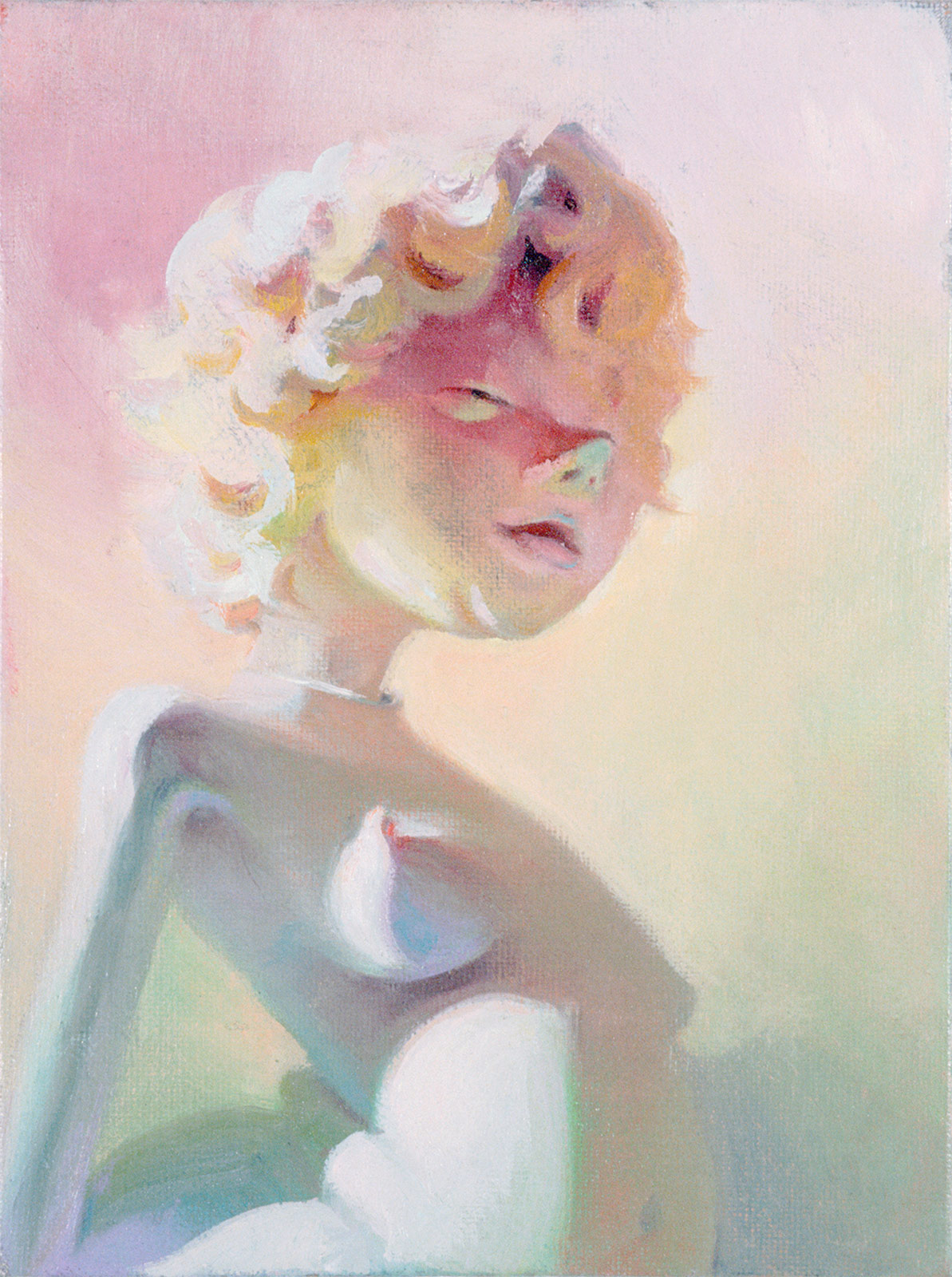

Lisa—There’s a combination of things because I think people are awkward. I guess I’ve experienced life that way. That was true to me, especially as a younger person. My earliest paintings were the Ground Zero of my work. These ‘Bad Baby’ paintings, and they were actually partially clothed, and they were paintings of pubescent, prepubescent girls. You weren’t even sure if they were girls. They sort of seemed [like] creature[s]. They were coming out of this kind of color mist. And they seem kind of partially funny and sort of partially angry, ashamed. I thought of them as beings that were describing how the paintings themselves felt. I felt like my paintings were these awkward little girls who want to go away, but were stuck with you looking at them. You know, like when you were a little girl and your nipples were sticking out, and you wish they wouldn’t. My paintings were kind of like, ‘I didn’t want to be looked at. I did want to be looked at. I didn’t want to be looked at.’ It was like this control thing. I noticed the relationship between those two moments in life, and I decided to try and make an object like that. That’s where my Ground Zero was, and that’s where my work started.

Ann—As a female painter, what kind of criticism and challenges did you face simply for being a woman in the art world?

Lisa—Pretty much just about everything. I’ve had challenges from the left and challenges from the right.

Ann—Was was the difference?

Lisa—The challenges from the left? I’ve had people say things like, ‘A man couldn’t get away with doing this.’ But in reality, men have been doing this for centuries. I actually quite love this review [that] said that by applying any criticality to my work, that the critic was deputizing the work. So basically, he was deputizing me by being critical of it. And I really kind of like that. I grew up in a scrappy way; I wasn’t raised in a privileged way. The scrappiness of all of that criticism worked for me. It was hard at first; nobody likes that sort of thing. But I learned to adapt to it. If you make work that’s kind of punchy, that is tough, I came to realize pretty quickly that you better expect a slap back.

Ann—Do you try to provoke in your work, or do you whatever the fuck you want to do?

Lisa—Sometimes I do whatever the fuck I want to do. I’m alone in my studio. It’s fun to be provocative. When I made pie-face painting with a girl on her knees with a bald vulva, got her tongue sticking out with a Ficus plant sitting in the background in an attic, I was having fun provoking. Who I was provoking is pretty vague. I was provoking myself. That’s the first person to be provocative towards—is myself. I’m a pretty conservative girl in a certain way. I’m married, and I actually pay my taxes. I’m not that wild in reality. I live in society; I’m not crazy. Some people think I’m actually pretty crazy. I actually pay my bills and stuff. I’m not a drug addict. I’m a more Apollonian in my life than Dionysian. But in my studio, I’m pretty Dionysian.

Ann—What are the differences between portraying masculinity and femininity in your work? Do you ever make the men feminine? Or the women masculine?

Lisa—Yeah, I think so. The guys in my paintings, a lot of people think are very feminine. I did a series of paintings where the women were kind of sitting on top of each other. I guess one was the top and [the other] almost [a] bottom. People were a little bit confused about whether or not those were about lesbianism. I think there’s a lot of ways to talk about women playing out that type of dynamic. I said, ‘Listen, I like the idea of it being about a lot of different things.’ I was interested in this idea that they’re two sides of the same person, where we’re splitting off from ourselves and sort of fighting with ourselves. I was thinking of a split self, but most people were like, ‘Is she gay?’, and I was like, ‘Okay, whatever, it’s fine.’ To do my kind of work, you have to be willing to let people think a lot of different things about you, and you have to be okay with it.

Ann—What about the role of the gaze in your work? I feel like your work is voyeuristic.

Lisa—All art is voyeuristic. Scopophilia is an interesting thing. We like to watch things and everybody does, whether or not they’d like to admit to it.

Ann—Do you think that your work empowers females?

Lisa—I think it depends on the female. Younger females seem to feel more empowered by it. My experience is really smart people get it, and a lot of smart younger people get it. I can’t really do much for people who aren’t smart. I don’t mean to be rude. There’s an older generation that seems to be quite hopeless about my work, because they’re stuck in a certain ideology. I am a very non-ideological person. I don’t subscribe to ideologies, and I don’t get stuck in them. I think for myself. The Pictures Generation, they’re just so generous to me. They came out of nowhere and told me, ‘You’re a wonderful artist.’ They’re of the generation that, like, some of that generation couldn’t handle the work. But I think great artists can see the work. If you’re a real artist, you can see what I’m doing. And I think if you’re not a real artist, you maybe can’t see what I’m doing. And I think if you’re somebody who’s got an open mind, you are a real artist. And if you’re smart, you have an open mind. I just feel like I can’t win them all.

Ann—Nobody can win over everybody.

Lisa—I do feel like the younger people are more open because they’ve had to be because [it’s going to] be very difficult to face what’s coming [in the future].

Ann—Do you have any advice for young female painters?

Lisa—Here’s my advice: Your mistakes are the only thing you can ever call your own. Don’t be afraid to lean into your mistakes. When people tell you you’re wrong, you have to really question because mistakes are unique, and getting it right is a thing that’s very questionable.

Ann—What about Aspen, winning the award, and your show here next spring?

Lisa—It’s great. I love the idea of being given an award. But I don’t think awards really mean that I’m better than any other artist; I think it’s really nice to get an award. I’m glad that people think I deserve an award, but I’m embarrassed by awards.