As historical sites are bulldozed daily, artists at JINGART 2019 reflect on the importance of the past.

At the JINGART fair in Beijing in May, a friend jokingly greets artist Shi Jinsong with the question, “Do you still have a studio?” Behind the playful dig is a dark reality: Beijing’s sprint to modernity has come at the expense of cultural spaces including historical sites, galleries, and art studios. Last year, Ai Weiwei caught the world’s attention by posting videos of his Soviet-style factory studio being demolished by the government without prior warning. Developers would much rather reuse the land for super-sized shopping malls and commercial buildings than leave it for artists to potter about them.

“It’s called urban revitalization,” Jingsong tells me at the fair. “It’s very common in Beijing.” Having your house or studio torn down for a commercial development is a near-perfect distillation of the quandary faced by many in China: How do you honor the past when rapid modernization threatens its erasure?

One of the ways this dichotomy plays out is through the adaption of tradition. Using detailed brush techniques, calligraphy, and detailed landscapes, Chinese ink art is one of the oldest continuous traditions in the world. Since its origin, nearly two and a half thousand years ago, it’s evolved to reflect modern life. Adored by the Chinese literati, over the past several years contemporary, experimental ink art has been doing very well at auctions. Though form varies from sculptures to realistic paintings, the continuity between old and new interpretations lies in both style and substance.

JINGART’s 2019 edition saw over 100,000 square meters in the Sino-Soviet style Beijing Exhibition Center occupied by galleries presenting new Chinese art. Outside, the building’s arches are dotted with the Soviet hammer and sickle motif, as inside the fair grapples with how to portray modern China.

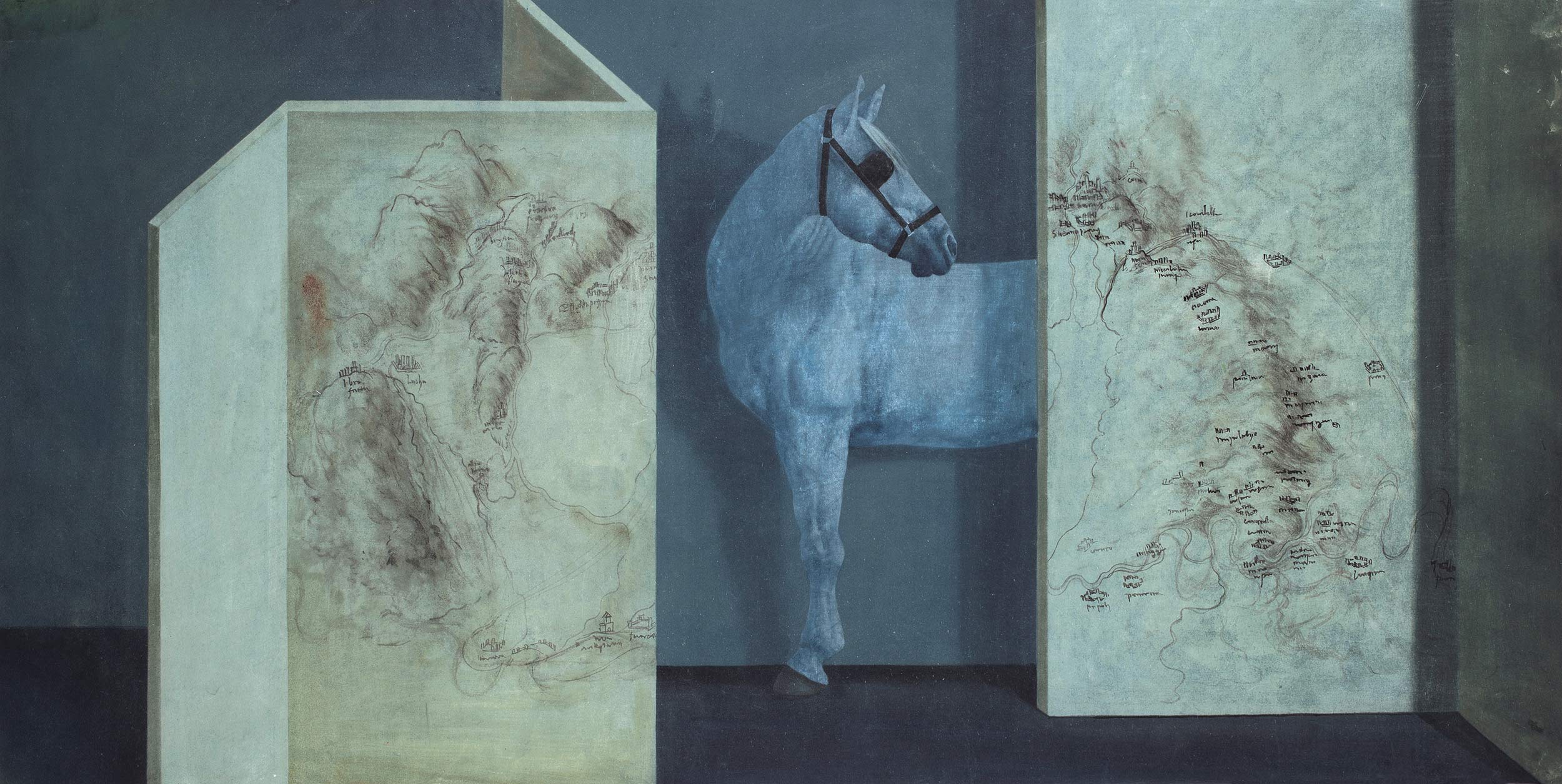

The fair’s biggest sale was Xu Lei’s 2015 drawing of a horse walking a tightrope. Inspired by Goya drawing, the equestrian focus of Lei’s artwork is about balance in an unstable world. “In the circus, this horse is, like, walking the line, swinging back and forth then right and left,” Lei tells me through a translator on the first day the fair is open to the public. “We have to make sure it’s very safe. It’s quite like people living in the current world, we need the ability to make sure that someone who can’t get down can.”

Shi Jinsong also uses balance as a prism to understand cultural heritage. He says working with cultural memory is like walking: by putting one foot in front of another you’re relying on what’s past moments to propel you forward. “The memory of the culture has to be changed to become the reality of our situation now,” he comments. “It’s like a handbook that helps us to see what’s going on now.”

Jingson’s approach mirrors the conceptual aspects of traditional ink art but the mediums are modern. Working with mixed media, sculpture, and digital and interactive elements, as well as ink on paper, he turns the philosophy on its head. At the fair, Jingsong shows me one of his sculptures. “This tree contains so many broken tiny twigs from the money tree. It’s a very Chinese traditional tree, and when it falls down on the ground, it’s like garbage and very dirty. But I just removed all those dirty things and just keep the most original part in my mind. It’s like the same with historical Chinese paintings.”

Lei speaks about his work similarly. “I am not realism,” Lei says. “My artwork is like a closed door where you can still feel the wind.” He comments that Chinese ink art is a spirit and not just a practice. “It’s like the inner spirit, he adds. “I don’t always talk about myself, but I can find some other thing like a horse, like a bird, or a chair in my artwork to illustrate that.”

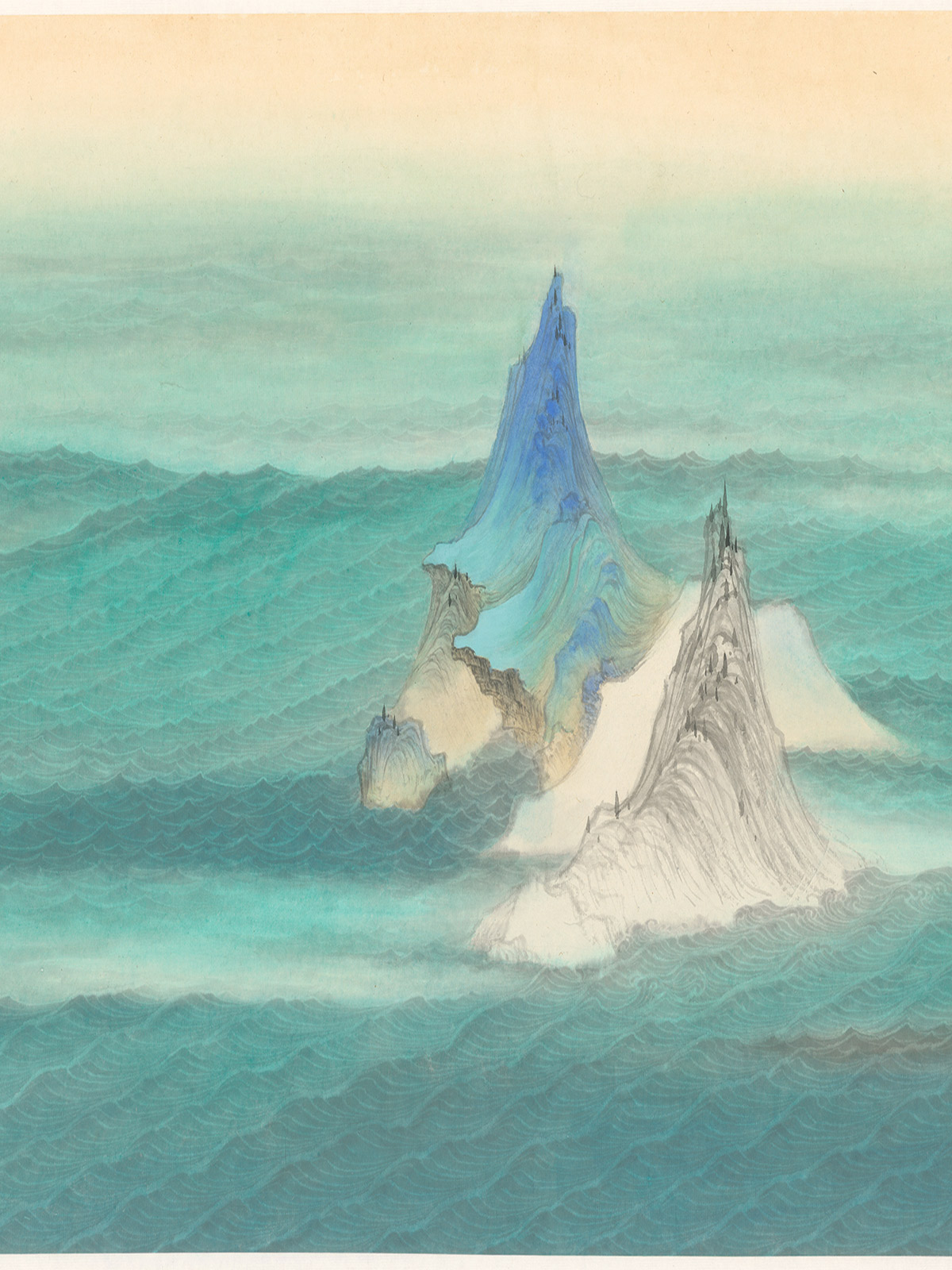

One of the core motifs of traditional Chinese art is nature. Landscapes, plants, and animals are revisited again and again as a way of understanding and paying tribute to the surrounding world. Wang Muyu is also an artist with a modern take on traditional ink art practices. Using two of China’s rudimentary resources, water and raw rice paper, he creates detailed and vivid landscapes. “In China we have worshiped water since very old time,” Muyu too tells me through a translator. ‘We have this special ideology and meaning for it.”

Unlike traditional interpretations of landscape painting in China, where students were expected to copy their master’s work without much creative input, Muyu’s paintings are entirely his own. “The relationship that I want to present to the society is not the relationship between what’s on the surface [of the paintings] and my life,” he explained to me. “It’s not like if I’m living around a lake, then I draw a lake, or if I’m near the sea, then I draw the ocean. It’s about the ideology or the personality of the water, [it] is like peace and calm. It’s my world and my thing.”