Timothy Greenfield-Sanders's documentary, 'Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am,' reveals the author's strength and sharp wit, surprising no one.

“I like the Nobel Prize,” Toni Morrison says, her expression somber as she nods her head slightly in affirmation. As the Nobel Prize winner completes her sentence, her face turns from grave to sly in a single moment. “I like the Nobel Prize… because they know how to give a party.”

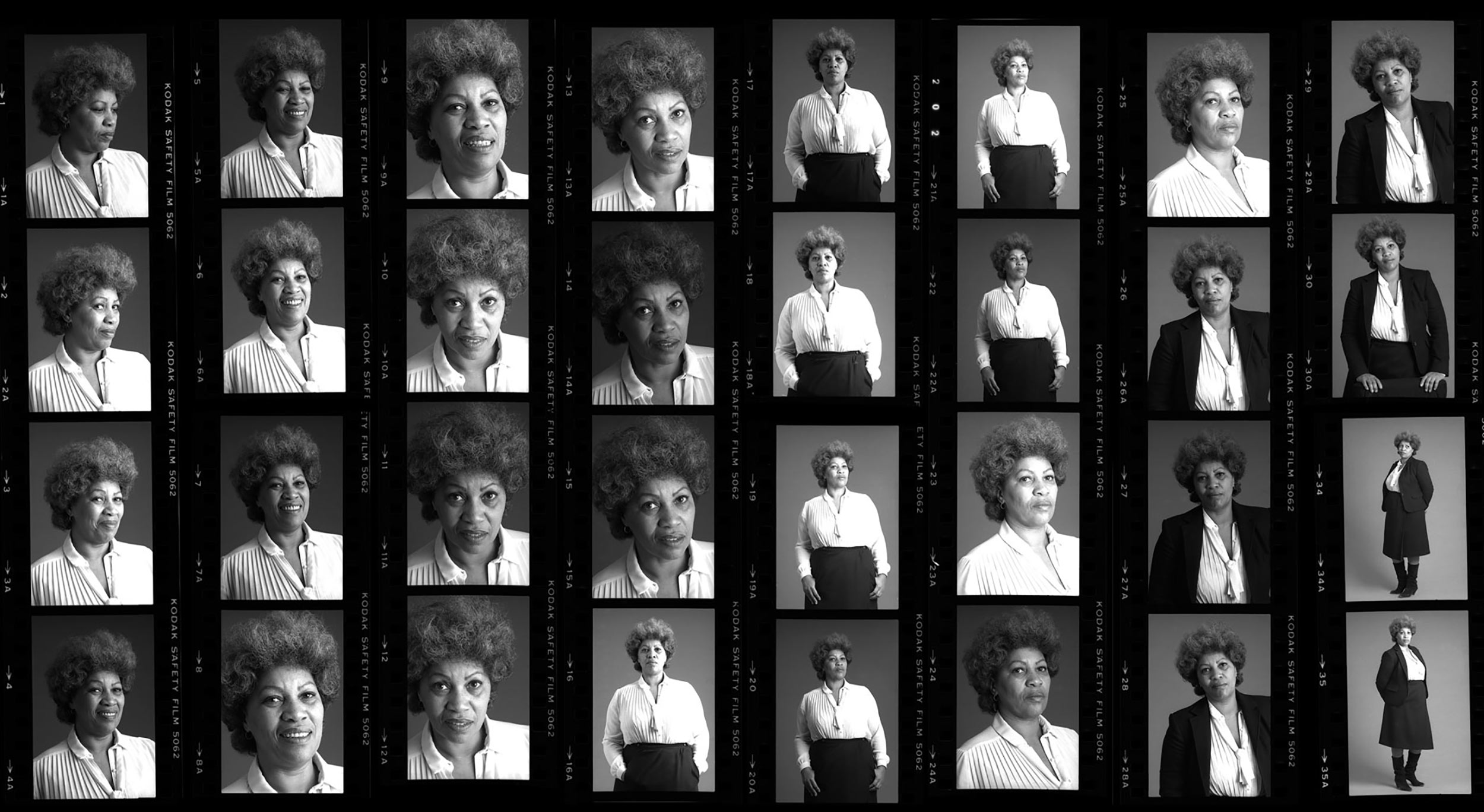

Toni Morrison likes to have fun. That much we learned early on in Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am, the documentary that chronicles the life and works of the acclaimed American author. Released on June 21, the film is directed by Morrison’s longtime friend, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders. It sells its protagonist as a multi-faceted woman, who, despite her immense literary prestige, doesn’t take herself too seriously. Through what Greenfield-Sanders describes as “little pods or vignettes” assembled in a non-linear format, the audience is taken through milestones in Morrison’s life. From the release of her first book, The Bluest Eye, to her years as a rising Random House editor, Morrison is presented as a scholar, a teacher, and a single mother. But unlike more traditional biographical documentaries, this isn’t an aspirational chronicle of a celebrity’s rise to fame. Instead, Greenfield-Sanders gives a refreshingly frank look into the woman behind a name. “There’s no gimmicks,” said the director. “It’s just the profoundness of Toni Morrison that comes through. We really wanted to make it about who Toni is and what she’s done and why she’s important.”

To that end, the batch of interviewees featured in this film were strategically curated, each person contributing to the portrait of Morrison with their own distinctive brushstrokes. Walter Mosely synthesizes Morrison’s work as “Shakespearean but pedestrian.” Fran Lebowitz recalls preparing for Morrison’s Nobel Prize celebrations, noting her friend’s love for presents and clothes. Oprah speaks of Morrison as an educator on pain. The poet Sonia Sanchez, pulling out her tattered copy of The Bluest Eye, mentions that she’s thrown the book across the room, only to find herself laughing moments later. “You read Toni and you cry but you gotta laugh,” she says. “If you don’t laugh, you know, you don’t survive.”

Absent from the film were any interviews with Morrison’s family members. When asked about the reasoning behind this decision, Greenfield-Sanders sighed. “I remember seeing a film on Warhol, and they interview his relatives,” he said before sighing once more. “To me, it was like what the fuck do his relatives know about Andy Warhol and his art? They don’t know anything!”

He quickly adds that this isn’t the case with Toni Morrison’s son. (“[Harold] Ford [Morrison] is in fact very versed in her work.”) But the message still stands. “I just don’t think that every documentary has to bring relatives in. I didn’t feel compelled to do that. And I don’t think it’s lacking. Do I need Ford saying, she’s a good mother? No. It feels like a testimonial to me.” In a world where female politicians are often scrutinized for their lipstick choices as much as they are for their policies, there is something to be said about how, despite frequent mention, Morrison’s children are kept peripheral to the central narrative. The distinction between a woman’s professional accomplishments and her family life provides a welcome perspective.

“Morrison recalls what it was like to work as an editor in a ‘white male world.’ ‘I was more interesting than they [white men] were,’ she remembers. With a spark in her eye, she adds, ‘and I wasn’t afraid to show it.’”

In the film, we get to see Morrison’s personality, learn about her accomplishments, and relish in her impact. But the tragedies in her personal life are respectfully kept obscure—we don’t learn about Morrison’s son, Slade Morrison, passing to pancreatic cancer in 2010, nor are we invited to dissect the 1993 Christmas Day fire that destroyed Morrison’s home. Instead, Morrison is empowered to explain her relationship to her family through anecdotes, like when her older son, Harold Ford, convinced her to let Oprah turn Beloved into the movie. There is a deliberateness to the nuance. It is what enables the director—a white man—to highlight events and people important in Morrison’s life without claiming any ownership over her identity. The result is not a biography, but rather a story that is glued together by Morrison’s own narration.

Morrison’s skilled, self-assured approach to life in the literary spotlight is a rousing running theme. In an interview from the early ՚80s, Dick Cavett suggests that Morrison must be “sickened to death of being labelled a ‘black writer.’” After clarifying that she in fact prefers the characterization, he expresses surprise that she’s not tired of it. “Well, I’m tired of people asking the question,” she laughs in a good-natured, but firm, retort. Watching Cavett’s embarrassed smile, it is not hard to imagine him as one of many put in his place by Morrison. In another shot from the film, Morrison recalls what it was like to work as an editor in a “white male world.” “I was more interesting than they [white men] were,” she remembers. With a spark in her eye, she adds, “and I wasn’t afraid to show it.”

Morrison shines when she recalls how her books have defied and engaged with social and institutional systems of racial oppression. For a few scenes, the documentary focuses on the censorship of The Bluest Eye in public schools across the U.S. Following this is a segment in which Morrison tells us of a framed letter that she keeps in her bathroom at home. “A letter from, I think, Texas Bureau of Corrections,” she recalls with a grimace. The letter said that her 1997 book, Paradise, had been banned from the prison because it risked inciting a riot. Morrison raises her eyebrows and cocks her head, chuckling, “I thought. How powerful is that? I could tear up the whole place!” Morrison’s fiery persona, thoughtful reflections, and affinity for humor emerge as the film’s biggest strength.

Greenfield-Sanders claims that Morrison had no involvement in the film other than the hours she spent being interviewed for it. “Her great line to me after looking at it [for the first time] was, ‘I like that person,’” he says with a laugh. That much isn’t hard to believe. After spending no more than 5 minutes in Toni Morrison’s presence, the audience knows to be enraptured too.